Nel vivere contemporaneo l’individuo tende sempre più spesso a intraprendere percorsi solitari, distaccati da quell’idea di comunità che invece era appartenuta alle generazioni precedenti; gli artisti stessi tendono a sottolineare il disagio causato dall’innegabile senso di solitudine a cui la vita moderna sottopone tutti. L’isolamento generato dalle moderne tecnologie e da un eccessivo uso del computer contribuisce ad acuire l’illusione di sentirsi parte di un gruppo che in realtà è solo apparente, effimero, privo di contatto umano. L’artista protagonista oggi sembra invece esortare l’uomo moderno a riconsiderare l’importanza di essere parte di un insieme più grande, quello che a volte spaventa, altre conforta, ma in ogni caso l’unico in grado di cancellare il timore latente di rimanere isolati, di poter smettere di esistere.

Nel momento in cui l’Espressionismo nacque e rivoluzionò il modo di intendere l’opera pittorica, di approcciarsi alla tela e di narrare le pulsioni più intime e a volte tormentate degli artisti che scelsero di aderire alla corrente seguendo la scia narrativa e le linee guida accennate dagli appena precedenti Fauves, si manifestò subito con un’irruenza, un pathos volti in special modo a liberare e a lasciar fuoriuscire tutto ciò che nel Diciannovesimo secolo non poteva essere espresso. Fino alla fine dell’Ottocento infatti il gesto creativo doveva ricercare la perfezione esecutiva, l’adesione a tutte le regole classiche e, soprattutto, la più fedele riproduzione della realtà; vi furono solo pochissime parentesi durante le quali alcuni pittori cercarono di dare rilevanza alle sensazioni, alle emozioni, o al mistero che spesso aleggia intorno al semplicemente visibile. Parlo ovviamente del Romanticismo, di cui William Blake fu splendido rappresentante, e del Simbolismo che si poneva come congiunzione tra la realtà oggettiva e la sensazione soggettiva; fu solo con l’avvicinarsi dei cambiamenti del Novecento che il mondo dell’arte cominciò a subire delle trasformazioni che rivoluzionarono la scala di valori, nonché dunque l’intento espressivo, e anche il modo di rendere la realtà sulla tela che divenne a quel punto un’estensione della propria interiorità. Tuttavia l’Espressionismo del primo trentennio del Ventesimo secolo fu legato principalmente a sensazioni di ansia, di angoscia, di disorientamento dopo che la guerra e tutto ciò che con sé aveva portato avevano turbato profondamente le coscienze, le sicurezze e gli animi dell’intera Europa e, inevitabilmente, anche degli artisti. L’angoscia di Edvard Munch, le maschere e i volti inquietanti di Emil Nolde, i paesaggi e le scene quotidiane cupe di Erich Heckel furono solo alcune delle declinazioni di questo stile pittorico in cui ciò che doveva prevalere era la soggettività dell’artista. Ma forse il più rappresentativo e ironico esponente della corrente fu Ernst Ludwing Kirchner che attraverso le sue tonalità vivaci e le sue figure longilinee e allungate intendeva dipingere un quadro preciso della frivolezza e vacuità della borghesia tedesca dei primi anni del Novecento. L’artista romana Loredana Giannotti riprende da Kirchner la tendenza a stilizzare e snellire i personaggi protagonisti delle sue tele senza però riproporre il tema della satira, al contrario, si percepisce invece la tendenza ad andare verso il gruppo, la consapevolezza della necessità di far parte di un insieme all’interno del quale ci si può sentire al sicuro.

Sembrano essere un invito alla convivialità le tele dell’artista, una sottolineatura di quanto in fondo ogni circostanza sia più reale, oltre che più bella, quando può essere condivisa e raccontata all’altro, al diverso da sé; la capacità di comunicare le emozioni, quel sentire interiore che aveva contraddistinto l’Espressionismo, è volto al positivo dalla Giannotti, al vedere il lato colorato e gioioso del vivere, alla sottile ironia in grado di sdrammatizzare anche le situazioni più formali oppure a quella capacità di intravedere e mettere in risalto una sensazione che potrebbe perdersi proprio all’interno della folla circostante, di quel gruppo di persone intorno. Eppure, sembra suggerire l’artista, la moltitudine potrebbe anche far sentire soli se non si è in grado di entrare in contatto con chi ci sta accanto, o intorno, perciò dipende dalla scelta e dalla facoltà del singolo di lasciarsi andare a quell’innata capacità di comunicare tipica della natura dell’essere umano, oppure restare in disparte come se si fosse dei semplici spettatori di tutto ciò che accade. Altra caratteristica peculiare di Loredana Giannotti è quella di sospendere il tempo perché i suoi soggetti potrebbero appartenere al passato come al presente, ciò che conta davvero è la loro tendenza alla convivialità, a quell’essere parte di una comunità, a volte civettuola, a volte più intensa, che segna i passi e i momenti importanti della vita.

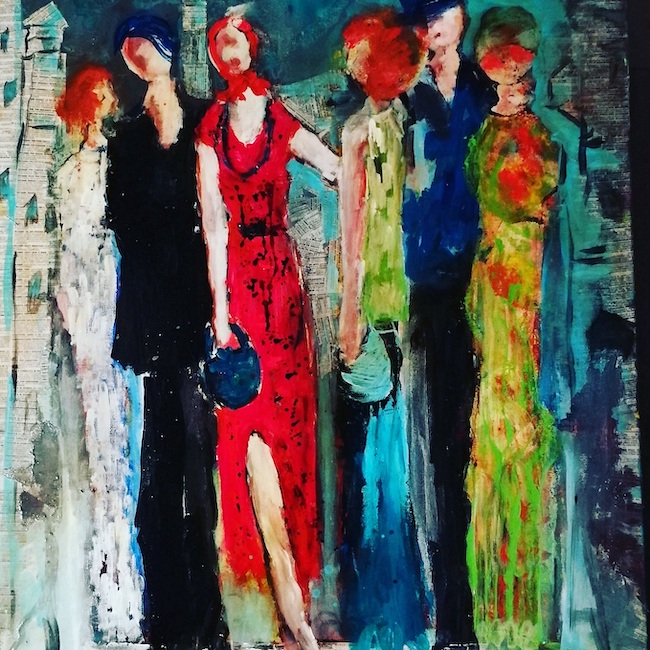

Nelle tele della serie People l’artista mette in risalto la parte più ludica, più mondana dei soggetti raffigurati sempre senza dettagli sul volto, proprio per sottolineare quanto sia fondamentale l’idea di insieme, quel riunirsi per divertimento, per interessi comuni, o semplicemente per passare una serata diversa che costituisce il fulcro della socialità di oggi come di ieri.

Ciò che invece è chiaramente espresso è la sensazione di piacevolezza che i suoi protagonisti provano nell’incontrarsi e nel condividere, quasi come se in fondo insieme fosse tutto più bello.

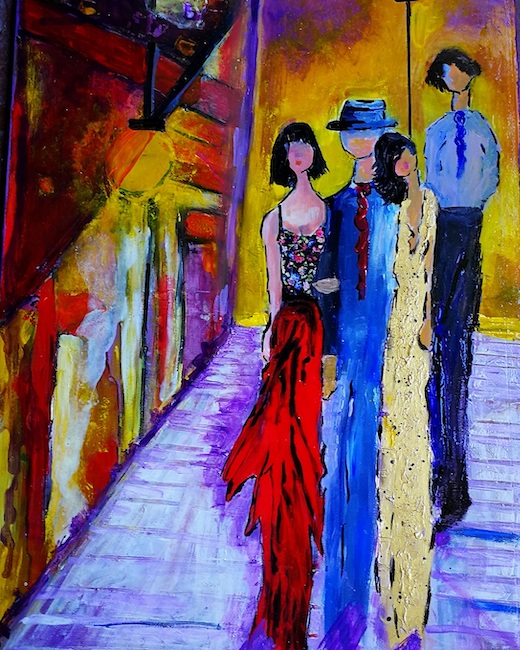

In Dance me to the end of love, al contrario la Giannotti punta il suo obiettivo su un istante, un attimo magico che traspare dall’atteggiamento dei due ballerini al centro della scena, al punto di riuscire a permeare l’atmosfera circostante di emozionante passione, e di attrarre al contempo gli sguardi un po’ gelosi e un po’ compiaciuti delle persone che si trovano intorno alla coppia. C’è sempre un’ambivalenza, una doppia possibilità interpretativa nelle immagini narrate dall’artista, perché tutto ciò che accade nell’esistenza può essere osservato da punti di vista differenti in base all’approccio che si ha, più positivo o più negativo, lasciando intendere che l’individuo può conoscere a fondo solo se stesso e le proprie emozioni e interpretare, dunque accogliendo o subendo, quelle degli altri.

Nell’opera Jazz il piacere dell’incontro e della condivisione si unisce alla musica che con le sue note semplici e ritmate è in grado da sola di generare emozioni che pervadono la sala in cui si trovano i musicisti. La cantante, senza volto come tutti i personaggi della Giannotti, riesce a comunicare la grazia e l’emozione nel lasciare che la voce si leghi alle note emesse dagli strumenti dei musicisti, a loro volta concentrati nell’esecuzione del brano, mentre il pubblico silente, posto alle spalle del punto di osservazione e dunque non visibile bensì solo intuibile, riceve quell’immagine di piacevolezza; è bravissima l’artista a lasciar fluttuare la sensazione ricevuta e ampliandola a un’immaginaria platea, come se l’ammirazione nei confronti del gruppo musicale fosse talmente tangibile da restare sospesa nell’aria e avvolgerli completamente.

I rossi, gli arancioni i galli sono le tonalità preferite di Loredana Giannotti, quelle attraverso le quali riesce a manifestare la sua emotività coinvolgente, affascinante e anche nostalgica nei confronti della capacità di apprezzare il bel vivere, di divertirsi e di apprezzare le piccole gioie quotidiane che molto spesso l’uomo contemporaneo tende a lasciare da parte compromettendo i rapporti umani. Loredana Giannotti ha esposto in numerose mostre in gallerie, centri culturali, biblioteche, all’Ambasciata d’Egitto, alla Grande Moschea, allo Stadio di Domiziano e nei sotterranei di Piazza Navona; fa parte dell’Associazione Esci di casa e ospite dell’Associazione Cento Pittori di via Margutta.

LOREDANA GIANNOTTI-CONTATTI

Email: logi@hotmail.it

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/loredana.giannotti.3

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/loredanagiannotti/?hl=it

Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/in/loredana-giannotti-23a14935/

The importance of the multitude in Loredana Giannotti’s Expressionism

In contemporary life the individual tends more and more often to take solitary paths, detached from the idea of community that belonged to previous generations; artists themselves tend to underline the unease caused by the undeniable sense of solitude to which modern life subjects everyone. The isolation generated by modern technology and excessive use of computers contributes to the illusion of feeling part of a group that in reality is only apparent, ephemeral and lacking in human contact. Today’s artist seems instead to be exhorting modern man to reconsider the importance of being part of a larger whole, one that sometimes frightens, sometimes comforts, but in any case the only one capable of erasing the latent fear of remaining isolated, of ceasing to exist.

When Expressionism was born, it revolutionised the way of understanding painting, of approaching the canvas and of narrating the most intimate and sometimes tormented impulses of the artists who chose to join the current, following the narrative trail and the guidelines hinted at by the earlier Fauves, it immediately manifested itself with an impetuousness, a pathos aimed in particular at freeing and letting out everything that could not be expressed in the 19th century. In fact, until the end of the 19th century, the creative gesture had to strive for perfection of execution, adherence to all the classical rules and, above all, the most faithful reproduction of reality; there were only very few brackets during which some painters tried to give importance to sensations, emotions or the mystery that often hovers around the simply visible.

I am of course talking about Romanticism, of which William Blake was a splendid representative, and Symbolism, which stood as a conjunction between objective reality and subjective sensation; it was only with the approach of the changes of the 20th century that the art world began to undergo transformations that revolutionised the scale of values, and therefore the expressive intent, and also the way of rendering reality on canvas, which then became an extension of one’s own interiority. However, the Expressionism of the first three decades of the 20th century was mainly linked to feelings of anxiety, anguish and disorientation after the war and all that it brought with it had profoundly disturbed the consciences, securities and souls of the whole Europe and, inevitably, of artists too. Edvard Munch’s anguish, Emil Nolde’s masks and disturbing faces, Erich Heckel’s landscapes and gloomy everyday scenes were just some of the declinations of this style of painting in which the subjectivity of the artist had to prevail. But perhaps the most representative and ironic exponent of the current was Ernst Ludwing Kirchner, whose bright colours and long-line and elongated figures were intended to paint a precise picture of the frivolity and vacuity of the German bourgeoisie in the early 20th century. The Roman artist Loredana Giannotti takes up Kirchner’s tendency to stylise and slim down the protagonists of her canvases without, however, re-proposing the theme of satire.

On the contrary, one perceives a tendency to move towards the group, an awareness of the need to be part of a whole within which one can feel safe. The artist’s canvases seem to be an invitation to conviviality, an underlining of how every circumstance is ultimately more real, as well as more beautiful, when it can be shared and told to others, to those different from oneself; Giannotti’s ability to communicate emotions, that inner feeling that distinguished Expressionism, is turned to the positive, to seeing the colourful and joyful side of life, to the subtle irony that can play down even the most formal situations, or to that ability to glimpse and highlight a feeling that could get lost in the surrounding crowd, in that group of people around. And yet, the artist seems to suggest, the crowd could also make feel lonely if one is not able to get in touch with those who are next to him, or around him, so it depends on the choice and the faculty of the individual to let go of that innate ability to communicate typical of the nature of the human being, or to remain aloof as if one were a simple spectator of everything that happens. Another peculiar characteristic of Loredana Giannotti is that of suspending time because her subjects could belong to the past or to the present, what really counts is their tendency to conviviality, to be part of a community, sometimes coquettish, sometimes more intense, which marks the steps and the important moments of life. In the paintings of People series, the artist emphasises the more playful, mundane side of the subjects, who are always depicted without any details on their faces, precisely to underline how fundamental the idea of togetherness is, that coming together for fun, for common interests, or simply to spend a different evening, which constitutes the fulcrum of sociality today as in the past. What is clearly expressed, however, is the sensation of pleasure that the protagonists feel when they meet and share, almost as if everything were better together.

In Dance me to the end of love, on the other hand, Giannotti focuses on an instant, a magical moment that transpires from the attitude of the two dancers at the centre of the scene, to the point of permeating the surrounding atmosphere with exciting passion, and at the same time attracting the slightly jealous and slightly smug glances of the people around the couple. There is always an ambivalence, a double possibility of interpretation in the images narrated by the artist, because everything that happens in existence can be observed from different points of view depending on one’s approach, either more positive or more negative, suggesting that the individual can only fully know himself and his own emotions and interpret, therefore accepting or suffering, those of others. In the painting Jazz, the pleasure of meeting and sharing is combined with music, which with its simple, rhythmic notes can alone generate emotions that pervade the room where the musicians are.

The singer, faceless like all Giannotti’s characters, succeeds in communicating the grace and emotion of letting her voice link up with the notes emitted by the musicians’ instruments, which are in turn concentrated on the execution of the piece, while the silent audience, placed behind the point of observation and therefore not visible but only intuitable, receives that image of pleasantness; the artist is very good at letting the sensation received float and expanding it to an imaginary audience, as if the admiration for the musical group were so tangible that it remained suspended in the air and enveloped them completely. The reds, oranges and yellows are Loredana Giannotti’s favourite colours, the ones through which she manages to express her engaging, fascinating and also nostalgic emotionality towards the ability to appreciate the good life, to enjoy oneself and to appreciate the small daily joys that very often contemporary man tends to leave aside, compromising human relationships. Loredana Giannotti has had numerous exhibitions in galleries, cultural centres, libraries, at the Egyptian Embassy, at the Great Mosque, at the Stadium of Domitian and in the underground of Piazza Navona; she is a member of the Art Arvalia Association and of Alternativa 94 and guest of the Cento Pittori di via Margutta Association.

LOREDANA GIANNOTTI-CONTACTS

Email: logi@hotmail.it

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/loredana.giannotti.3

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/loredanagiannotti/?hl=it

Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/in/loredana-giannotti-23a14935/