La società attuale tende verso una globalizzazione e un’uniformità di pensiero e di dinamiche sociali che spesso dimenticano l’individualismo, inteso nel senso ampio del termine e dunque non nella sua accezione più negativa, per prediligere la tendenza a divenire parte di un ipotetico gruppo, quello virtuale, che in realtà pur infondendo l’illusione di essere parte di una grande comunità globale, in realtà conduce a un isolamento sempre più profondo in cui si perde la propria vera essenza. Questo è il tema su cui si focalizzano le opere dell’artista di cui vi parlerò oggi.

Nel momento in cui si delineò l’impulso a lasciar prevalere le sensazioni interiori sulla forma esterna, tutti i canoni estetici, prospettici, coloristici, persero il loro senso e il loro rigore accademico si dissolse di fronte all’impetuosità degli artisti aderenti alla corrente dell’Espressionismo che accettavano persino il brutto, il deforme, l’inquietante, se si accordava allo stato d’animo del momento in cui si apprestavano a dipingere. Spesso gli aderenti al movimento utilizzavano colori cupi e tenebrosi per rappresentare il disagio interiore che i venti di guerra di quei primi decenni del Ventesimo secolo portavano con sé, come nelle tumultuose tele di Edvard Munch, oppure per dissacrare e osservare con sarcasmo la società borghese dell’epoca, tipico delle opere di Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, o per evidenziare la tragicità che si nascondeva dietro le pieghe della quotidianità che contraddistingueva i dipinti di Oskar Kokoschka. Non solo, anche la follia di un male di vivere troppo difficile da sopportare se non evadendo attraverso la manifestazione creativa fu una delle molteplici declinazioni del movimento, declinazione che caratterizzò la produzione artistica di Vincent Van Gogh. Il tema della deformazione dei soggetti riprodotti, per esprimerne il sentire interiore piuttosto che l’apparenza di una superficie che non riceveva alcun interesse dagli espressionisti, fu ripreso e ampliato dal gruppo di artisti appartenenti alla Scuola di Londra, di cui fecero parte tra gli altri Lucien Freud e Francis Bacon, entrambi tesi a esplorare l’essere umano, il primo attraverso le sue debolezze interiori che non potevano non armonizzarsi all’esteriorità, il secondo invece sottolineando la perdita di identità, di dignità e di umanità che aveva subìto la popolazione europea durante la seconda guerra mondiale. In particolar modo i volti di Bacon esprimevano il disorientamento, il dolore, che si traducevano in perdita di identità figurativa, i suoi personaggi non erano riconoscibili perché non contava chi fossero bensì quanto avessero perduto nel cammino intrapreso fino a quel momento, quanto la loro identità si fosse dissolta dentro gli orrori della guerra. Nell’era contemporanea quelle sofferenze sembrano essere ormai lontane, superate, per dare spazio a un approccio differente da parte degli artisti seppure costantemente orientato a osservare e studiare quanto sia importante il contatto con un’interiorità che non dovrebbe mai dimenticarsi di sé, non dovrebbe mai lasciarsi affascinare dall’effimero, dalla superficie lucente che induce l’essere umano a perdere la propria identità. L’artista greco George Androutsos, le cui opere sono apparse persino in alcune serie televisive della sua nazione, va esattamente nella medesima direzione di Bacon, pur tralasciando la tendenza alla crudezza e alla violenza visiva delle tele del maestro del Novecento e spostando l’attenzione sull’esistenzialismo contemporaneo, quella necessità intrinseca di affermare la propria personalità all’interno della società malgrado la consapevolezza di quanto l’uomo sia spesso considerato un mero numero.

Eppure, oltre il conformismo, sembra dire l’artista, si delineano soggettività, caratteri, emozioni che restano sotterranei, latenti e tuttavia fortemente presenti, forse timorosi di esprimersi perché preoccupati di non allinearsi con ciò che l’esterno vuole da loro ma desiderosi di lasciar trapelare in qualche modo la propria identità, quell’individualismo che non può fare a meno di emergere, malgrado tutto.

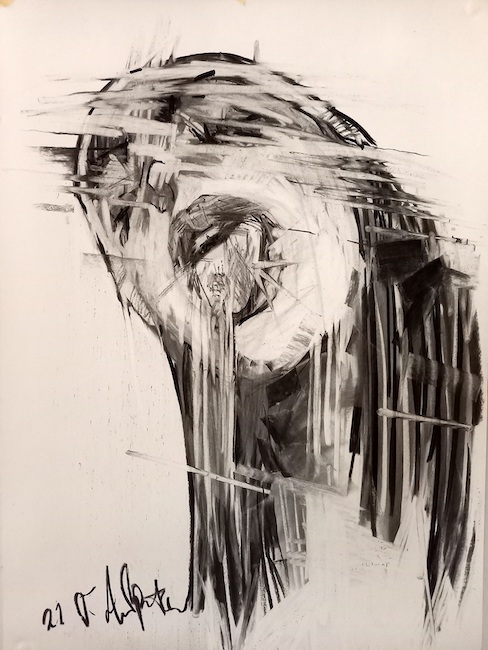

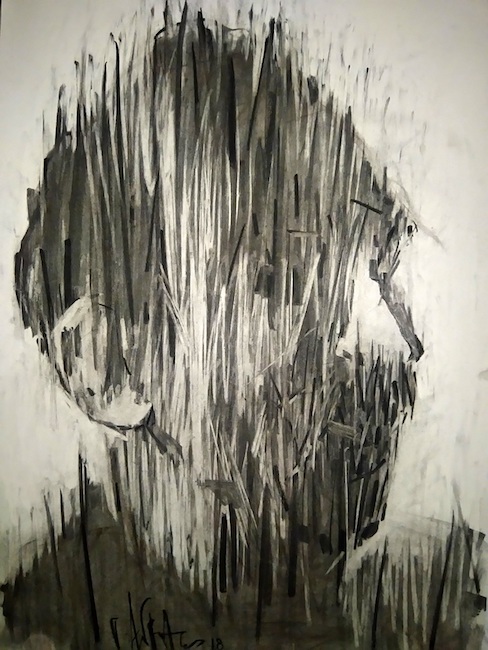

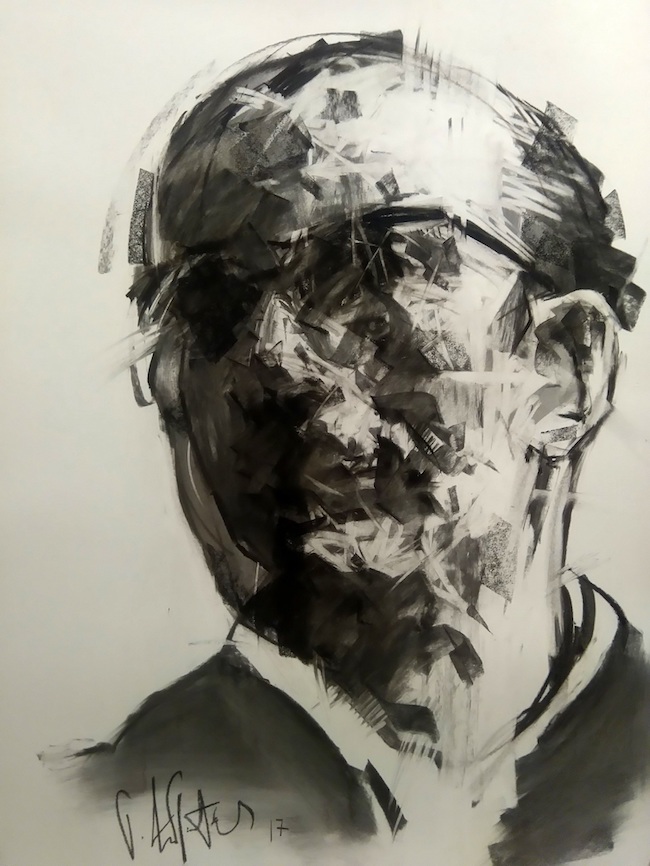

La tecnica usata da George Androutsos è quella del carboncino su carta attraverso cui esegue prima il ritratto in stile realista, e successivamente interviene per cancellarne i tratti ponendo l’accento su quella tendenza a celare la propria essenza lasciando emergere invece l’apparenza in virtù della quale è necessario indossare una maschera, riconducendosi così a quell’Uno, nessuno e centomila di cui Luigi Pirandello tanto ha raccontato.

Si ha come la sensazione di trovarsi di fronte a una sovrapposizione di realtà guardando le opere di George Androutsos, o forse a un inganno, quello che appartiene alla quotidianità, che induce l’individuo a soffermarsi solo distrattamente sui volti incontrati tutti i giorni e mai osservati davvero, un po’ perché gli altri si chiudono presi dai propri pensieri e dalla propria vita, un po’ perché nella società contemporanea andare a fondo e approfondire una conoscenza sembra essere troppo impegnativo rispetto alla facilità e all’immediatezza del contatto virtuale che non costringe ad aprirsi perché protegge inducendo l’individuo a fingere con facilità di essere altro da ciò che realmente è.

Fortemente indicativo dell’orientamento esistenzialista di Androutsos è il ritratto dedicato ad Albert Camus, lo scrittore-filosofo dell’assurdo inteso come condizione umana, quell’essere costantemente in bilico tra necessità di solitudine e tendenza verso la comunità, quel non riuscire a comprendere un senso della vita che spesso induce a rifiutare la possibilità di essere felici proprio a causa degli eventi che si susseguono e che sembrano sfuggire al controllo dell’uomo.

La risposta secondo Androutsos sta nella scelta, in quel fugace frangente in cui decidere se lasciarsi andare all’invisibilità oppure se compiere un’azione che possa modificare il corso degli eventi e dunque lasciar trapelare i tratti della personalità, quelli che emergono debolmente dai suoi ritratti ma che sono fortemente presenti sotto il velo di apparenza mantenuta per aderire allo stato delle cose. Le personalità celate raccontate dall’artista sono molteplici, a volte irriverenti, altre formali, altre ancora seriose, e poi vi sono quelle più indistinguibili perché l’attitudine del protagonista narrato è quella di adeguarsi con maggiore facilità agli accadimenti, di essere prismatico nel senso meno positivo del termine, al punto di cancellare la propria identità, di fatto dimenticandola egli stesso pur di assecondare il mondo circostante, chi gli sta intorno, dando ciò che gli altri si aspettano da lui.

L’opera Untitled 7 evidenzia e sottolinea questo concetto, quell’annullamento completo di un’individualità che preferisce soccombere piuttosto che non corrispondere alle richieste che provengono dall’esterno, quel bisogno di appartenere a un gruppo, a una realtà spesso persino lontana dalla propria essenza ma necessaria per sentirsi accettato e accolto; il rischio, sembra voler dire l’artista, è quello di dimenticarsi di sé, di perdersi dentro un abito che non è il proprio e che prima o poi richiederà di liberarsi dall’oppressione del non potersi manifestare, del dover restare silente spettatore di una vita non corrispondente a quella che avrebbe potuto vivere se non si fosse piegato all’ingerenza esterna.

In Untitled 8 invece la sfaccettatura mostra la persistenza della volontà del personaggio di restare ancora fedele a se stesso, a non volersi uniformare pur essendo consapevole dell’esigenza di convivere con una contingenza davanti alla quale deve essere camaleontico ma senza rinunciare a quelle caratteristiche che lo contraddistinguono, che lo rendono unico in mezzo alla moltitudine; la sua essenza dunque prevale sulla richiesta di conformarsi all’esterno, indossando una maschera che però viene tolta non appena l’individuo si trova solo con se stesso e può tornare a far fuoriuscire la sua vera identità. George Androutsos, ha all’attivo tre mostre personali in Grecia e in Francia, ha partecipato a mostre collettive in Grecia e in molti paesi del mondo, tra cui Spagna, Italia, Francia, Belgio, Giappone, Usa, Macedonia, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Repubblica Ceca, ricevendo importanti premi e riconoscimenti.

CONTATTI-GEORGE ANDROUTSOS

Email: gandrouart@gmail.com

Sito web: https://www.behance.net/gandrout

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/george.androutsos.1

Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/in/george-androutsos-6940a197/

Pinterest: https://www.pinterest.it/gandrousm/

The erased faces of George Androutsos, between hidden identities and contemporary man’s need to impose himself

Today’s society tends towards globalisation and a uniformity of thought and social dynamics that often forget individualism, understood in the broadest sense of the term and therefore not in its most negative meaning, in favour of the tendency to become part of a hypothetical group, the virtual one, which in reality, while giving the illusion of being part of a large global community, leads to an ever deeper isolation in which loosing the true essence. This is the theme on which the artworks of the artist I am going to talk about today focus.

As the impulse to let inner feelings prevail over external form took shape, all aesthetic, perspective and colouristic canons lost their meaning and their academic rigour dissolved in front of the impetuousness of the artists belonging to the current of Expressionism who even accepted the ugly, the deformed, the disturbing, if it suited the mood of the moment they were painting. Often the adherents of the movement used dark and gloomy colours to represent the inner unease that the winds of war in those first decades of the 20th century brought with them, as in the tumultuous paintings of Edvard Munch, or to desecrate and observe with sarcasm the bourgeois society of the time, typical of the artworks of Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, or to highlight the tragedy hidden behind the folds of everyday life that distinguished the canvases of Oskar Kokoschka. Not only that, but also the madness of a bad way of life too difficult to bear if not by escaping through creative manifestation was one of the multiple declinations of the movement, a declination that characterised the artistic production of Vincent Van Gogh.

The theme of the deformation of the subjects reproduced, to express their inner feelings rather than the appearance of a surface that was of no interest to the Expressionists, was taken up and expanded by the group of artists belonging to the School of London, which included Lucien Freud and Francis Bacon, both of whom sought to explore the human being, the former through his inner weaknesses that could not fail to harmonise with the exterior, the latter by emphasising the loss of identity, dignity and humanity that the European population had suffered during the Second World War. Bacon’s faces in particular expressed disorientation, pain, which translated into a loss of figurative identity, his characters were not recognisable because it did not matter who they were but how much they had lost in the journey they had undertaken up to that moment, how much their identity had dissolved within the horrors of war. In the contemporary era, these sufferings seem to be long gone, overcome, to make room for a different approach on the part of artists, even if constantly oriented towards observing and studying how important it is to be in contact with an interiority that should never forget itself, should never allow itself to be fascinated by the ephemeral, by the shiny surface that induces human beings to lose their identity.

The Greek artist George Androutsos, whose artworks have even appeared in some of his country’s television series, is going in exactly the same direction as Bacon, although he leaves aside the tendency towards rawness and visual violence of the twentieth-century master’s canvases and shifts his attention to contemporary existentialism, that intrinsic need to affirm one’s personality within society despite the awareness of how man is often considered a mere number. And yet, beyond conformism, the artist seems to be saying, there are subjectivities, characters and emotions that remain subterranean, latent and yet strongly present, perhaps afraid to express themselves because they are worried about not aligning themselves with what the outside world wants from them, but eager in some way to let their identity emerge, that individualism that cannot help but emerge, despite everything. The technique used by George Androutsos is charcoal on paper, through which he first paints a portrait in a realist style, and then erases the features, emphasising the tendency to conceal one’s own essence, leaving instead the appearance to emerge, by virtue of which it is necessary to wear a mask, thus leading back to that One, No One and a Hundred Thousand of which Luigi Pirandello spoke so much. One has the feeling of being faced with a superimposition of reality when looking at the drowings of George Androutsos, or perhaps a deception, which belongs to everyday life, which induces the individual to dwell only distractedly on the faces he meets every day and never really observes, partly because others close themselves off from each other, caught up in their own thoughts and lives, and partly because in today’s society to go into depth and deepen a knowledge it seems too challenging, compared to the ease and immediacy of virtual contact, which does not force to open up, because it protects, inducing the individual to easily pretend to be something other than what he really is.

Androutsos’s portrait of Albert Camus, the writer-philosopher of the absurd as the human condition, is strongly indicative of his existentialist orientation, that being constantly caught between the need for solitude and the tendency towards community, and the inability to understand the meaning of life, which often leads man to reject the possibility of happiness precisely because of the events that follow one another and seem to escape human control. According to Androutsos, the answer lies in the choice, in that fleeting moment in which to decide whether to let oneself go into invisibility or to perform an action that can change the course of events and thus allow personality traits to emerge, those that emerge weakly from his portraits but are strongly present under the veil of appearance maintained to adhere to the state of things. The hidden personalities recounted by the artist are many, sometimes irreverent, others formal, others serious, and then there are those that are more indistinguishable because the attitude of the protagonist narrated is that of adapting more easily to events, of being prismatic in the least positive sense of the term, to the point of erasing his own identity, in fact forgetting it himself in order to comply with the surrounding world, those around him, giving what others expect of him.

The work Untitled 7 highlights and underlines this concept, that complete cancellation of an individuality that prefers to succumb rather than not correspond to the demands that come from outside, that need to belong to a group, to a reality that is often even distant from one’s own essence but necessary to feel accepted and welcomed; the risk, the artist seems to want to say, is that of forgetting, of losing oneself in a garment that is not one’s own and that sooner or later will require liberation from the oppression of not being able to manifest, of having to remain a silent spectator of a life that does not correspond to the one that could have beeb lived if one had not bowed to external interference. In Untitled 8, on the other hand, the facet shows the persistence of the character’s desire to remain true to himself, to not want to conform even though he is aware of the need to live with a contingency in the face of which he must be chameleon-like, but without renouncing those characteristics that distinguish him, that make him unique among the multitude; his essence therefore prevails over the demand to conform to the outside, wearing a mask that is however removed as soon as the individual is alone with himself and can once again reveal his true identity. George Androutsos has had three solo exhibitions in Greece and France, and has taken part in several group exhibitions in Greece and in many countries around the world, including Spain, Italy, France, Belgium, Japan, the USA, Macedonia, Bosnia-Herzegovina and the Czech Republic, receiving important prizes and awards.