Affrontare e spiegare quel complesso quanto spesso enigmatico mondo della donna, è un percorso intrapreso già da molti artisti del passato che si sono soffermati sull’estetica, sul fascino magnetico esercitato dalla grazia e dall’armonia femminili, per tentare di raccontare quei dettagli intuiti e mai spiegati, lasciando all’osservatore la sensazione di aver aperto solo un piccolissimo spiraglio sulla vera essenza delle protagoniste immortalate. Sì perché ciascuna donna, come d’altronde ogni essere umano, racchiude in sé un’infinità di sfumature e dettagli unici nella loro combinazione e dunque sfuggenti al tentativo di poterli cogliere e spiegare; l’artista di cui vi parlerò oggi si spinge così verso un’interpretazione più ampia, affidando a diverse protagoniste alcune delle principali caratteristiche che appartengono alle fasi e ai momenti di vita di una donna.

Nel corso della storia dell’arte vi sono state poche grandi protagoniste femminili, pioniere di una libertà espressiva che solo nel Novecento ha potuto consolidarsi e liberarsi dai limiti imposti da una società in cui l’uomo era al centro dei ruoli più importanti, e non ultimo quello della creatività. Solo alcune privilegiate e coraggiose figure come Artemisia Gentileschi, Rosalba Carriera e Angelika Kauffman, unica donna tra i fondatori della Royal Academy of Arts, riuscirono a uscire dall’ombra ma di fatto fu necessario attendere la fine dell’Ottocento prima di veder delinearsi in maniera più solida la presenza delle artiste nel panorama internazionale. Berthe Morisot, impressionista, mostrò una delicata sensibilità espressiva creando atmosfere avvolgenti e dolci in cui la donna era assoluta protagonista, con i suoi gesti quotidiani, con la sua capacità di essere materna, sensuale, sfrontata e rilassata; tanto quanto Suzanne Valadon mostrò attraverso il suo inconfondibile Espressionismo, la sottile malinconia che permeava le sue donne, costantemente messe in secondo piano da un mondo ancora troppo maschilista per accogliere un’emancipazione ormai necessaria, neanche se legata al talento. Nel Ventesimo secolo le artiste dovettero ancora lottare per riuscire a emergere, a dimostrare quanto il dono della creatività fosse prerogativa di chi lo possedeva indipendentemente dal sesso di appartenenza, così le opere di Frida Khalo erano permeate dal desiderio dell’artista di porsi in primo piano, di raccontare la sua interiorità, le sofferenze, la necessità di mettersi al centro del suo mondo in maniera impositiva, forte, determinata. E ancora Tamara de Lempicka sottolineò la raffinatezza e al tempo stesso l’indipendenza di figure femminili di grande impatto, lasciando sotto la patina estetica tutte quelle emozioni racchiuse nell’animo, forse per timore di apparire fragili o deboli. E poi ancora Paula Rego che con atmosfere tra fiaba e realtà denunciò la condizione arretrata delle donne nel Portogallo di Salazar, e Margareth Keane che dovette combattere contro il marito per affermarsi come autrice delle meravigliose opere dai grandi occhi. Insomma, il mondo femminile, nella vita come nell’arte, ha costantemente dovuto imporsi con forza per riuscire a far sentire la propria voce e permettere alle artiste contemporanee di esprimersi senza dover combattere bensì semplicemente lasciando fuoriuscire liberamente le proprie emozioni, le sensazioni che appartengono alla delicatezza del proprio animo. Stefania Miceli, artista bolzanina che da sempre sceglie un approccio pittorico morbido e denso di atmosfera quasi magica, dedica la sua ultima produzione proprio al mondo femminile, affidando a ciascuna protagonista il ruolo di interpretare un’emozione, una caratteristica specifica che si amplia divenendo peculiarità identificativa dei gesti e delle pose in cui ritrae le sue donne.

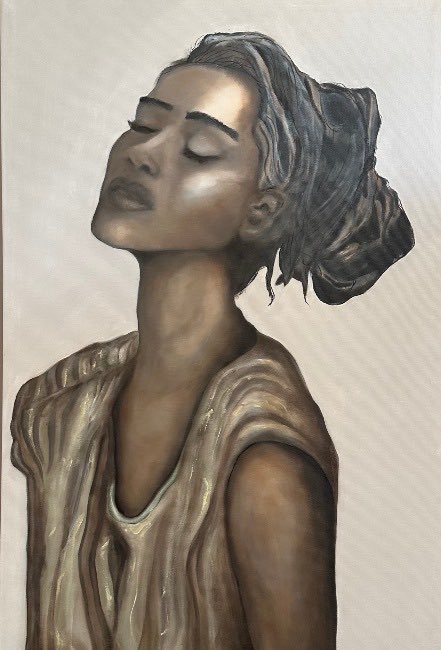

Il suo stile tende verso l’Espressionismo pur sovvertendone in qualche modo le regole poiché la tecnica è spesso mista, si muove tra il più tradizionale olio su tela e l’acrilico misto a gesso successivamente spatolato, per infondere nell’osservatore una maggiore suggestione, un’atmosfera concreta ma al tempo stesso impalpabile con cui la Miceli avvolge i personaggi femminili, come se il punto focale di ogni tela fosse non solo il centro, e dunque la figura, bensì l’intero spazio intorno alla donna. In tal modo viene posto l’accento su quanto la realtà circostante si adegui al sentire interiore, quanto tutto ciò che accade intorno all’individuo sia in qualche modo determinato dal suo modo di porsi nei confronti dell’esistenza; le peculiarità di ogni singola protagonista vengono esaltate di opera in opera dallo sguardo, oppure da un abito, o ancora da un gesto specifico che identifica la particolarità a cui il personaggio si lega.

La gamma cromatica è quasi sempre molto tenue, sfumata, in alcuni casi persino vicina alla scala di grigi, perché in fondo anche le emozioni sono spesso sussurrate, così come le consapevolezze vengono lasciate emergere nell’intimità dell’introspezione, nel momento in cui il mondo è chiuso fuori o sembra non osservare. È proprio quello l’istante in cui Stefania Miceli posa il suo sguardo sulle sensazioni fuoriuscite e le imprime sulla tela dando così una panoramica su quelle qualità che appartengono all’animo femminile e che nella contemporaneità non hanno più bisogno di celarsi o rimanere silenziose.

In Determinazione, approccio caratteriale imprescindibile per raggiungere il risultato e gli obiettivi prefissati, Stefania Miceli mette in evidenza gli occhi della ragazza, da cui fuoriesce un misto di sfida, di sicurezza in se stessa e di pragmatismo nel perseguire un desiderio, un sogno; ciò che conta non sono i dettagli, sembra suggerire l’artista attraverso l’indefinitezza di tutto ciò che nel dipinto non si lega allo sguardo, bensì il fine, quel raggiungimento che diviene progetto da realizzare proprio in virtù della risolutezza necessaria a imporsi sulla realtà circostante. Le sottili linee grafiche, quasi simili a graffi, sono metafora dei potenziali ostacoli che possono frenare il raggiungimento del risultato ma non sufficienti ad arginare la voglia di farcela della protagonista.

Nell’opera Solitudine invece, condizione in cui spesso la donna si ritrova a seguito di scelte inevitabili oppure in cui si rifugia quando sente la necessità di ritrovare se stessa, il volto è nascosto da un grande cappello a tele larghe, come se il bisogno di astrarsi da tutto ciò che la circonda, e che potrebbe distoglierla dal suo percorso di presa di coscienza, fosse il presupposto fondamentale a completare quel cammino. La solitudine non è dunque interpretata con accezione negativa, tutt’altro, sembra al contrario costituire una fase piacevole, serena, di grande equilibrio da cui poi ripartire per scegliere di mettere fine a quel periodo.

Nel dipinto Trasgressione di contro, Stefania Miceli pone l’accento sull’irriverenza, sull’essere fuori dagli schemi che in qualche occasione diventa necessario per ribellarsi alle circostanze, per affermare la propria indipendenza, per dire no a tutte le regole che limitano la libertà personale, che chiedono di attenersi alle convenzioni; traspare una sottile ironia nello sguardo della pittrice, percepibile attraverso l’atteggiamento della protagonista volutamente eccessivo, esagerato, in cui i vizi si concentrano per enfatizzare la sua decisione di essere, per un periodo più o meno lungo, sopra le righe. Le tonalità tendenti al seppia accompagnano la posa impertinente della donna, concentrando l’attenzione sul suo piglio sfrontato da cui traspare l’irremovibilità nell’essere ciò che vuole.

Dunque Stefania Miceli pone i suoi personaggi femminili di fronte all’osservatore quando devono esprimere sensazioni forti e incisive, mentre preferisce immortalarle di spalle nei momenti in cui le loro fragilità potrebbero fuoriuscire, oppure quando hanno bisogno di riflettere, di meditare su se stesse; come in Dubbi, una delle rare opere in cui è presente una gamma cromatica più intensa, dove la ragazza non mostra il volto, sembra guardare un punto indefinito e lontano, davanti a sé eppure apparentemente inarrivabile a causa delle perplessità, dell’indecisione che un particolare evento, o una scelta, hanno determinato. Qui il gesso crea delle increspature sulla tela, come ad apporre un elemento disturbante, un punto di leggera rottura tra la realtà creduta, o immaginata, e quella che invece l’incertezza porta alla luce come possibile. L’atteggiamento del corpo lascia emergere un’immobilità interiore, una paralisi di indecisione da cui la protagonista potrà uscire solo quando troverà la forza di prendere in mano la situazione e compiere la scelta.

Stefania Miceli ha al suo attivo numerose mostre collettive ed è socia dell’associazione Club Arcimboldo di Bolzano; dal 7 al 23 giugno la serie di opere dedicata alle donne sarà protagonista della sua prima mostra personale all’Hotel Sheraton di via Bruno Buozzi a Bolzano.

STEFANIA MICELI-CONTATTI

Email: stefaniamiceliarte@yahoo.com

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/stefania.miceli.3363

https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100085692351635

The thousand facets of the female universe in Stefania Miceli’s delicate Expressionism

Tackling and explaining that complex and often enigmatic world of women is a path already taken by many artists of the past who have dwelt on aesthetics, on the magnetic charm exerted by feminine grace and harmony, in an attempt to recount those details intuited and never explained, leaving the observer with the sensation of having opened only a tiny glimmer of the true essence of the protagonists immortalised. Yes, because each woman, like every human being, contains an infinity of nuances and details that are unique in their combination and therefore elusive to the attempt to grasp and explain; the artist I am going to tell you about today thus pushes towards a broader interpretation, entrusting different protagonists with some of the main characteristics that belong to the phases and moments of a woman’s life.

Throughout the history of art there have been few great female protagonists, pioneers of an expressive freedom that only in the 20th century was able to consolidate and free itself from the limits imposed by a society in which men were at the centre of the most important roles, not least that of creativity. Only a few privileged and courageous figures such as Artemisia Gentileschi, Rosalba Carriera and Angelika Kauffman, the only woman among the founders of the Royal Academy of Arts, were able to step out of the shadows, but in fact it was necessary to wait until the end of the 19th century before the presence of women artists on the international scene became more solidly defined. Berthe Morisot, an Impressionist, showed a delicate expressive sensitivity by creating enveloping and sweet atmospheres in which women were the absolute protagonists, with their daily gestures, with their ability to be maternal, sensual, cheeky and relaxed; just as Suzanne Valadon showed through her unmistakable Expressionism, the subtle melancholy that permeated her women, constantly put in the background by a world that was still too male chauvinist to welcome an emancipation that was by then necessary, even when linked to talent. In the 20th century, women artists still had to struggle to emerge, to demonstrate how the gift of creativity was the prerogative of those who possessed it regardless of their gender, thus Frida Khalo‘s paintings were permeated by the artist’s desire to place herself in the foreground, to recount her interiority, her sufferings, the need to place herself at the centre of her world in an imposing, strong, determined manner. And then again Tamara de Lempicka emphasised the refinement and at the same time the independence of female figures of great impact, leaving under the aesthetic patina all those emotions enclosed in the soul, perhaps for fear of appearing fragile or weak. And then again Paula Rego, who with atmospheres between fairy tale and reality denounced the backward condition of women in Salazar’s Portugal, and Margareth Keane who had to fight her husband to establish herself as the author of the wonderful big-eyed works. In short, the female world, in life as in art, has constantly had to assert itself in order to make its voice heard and allow contemporary female artists to express themselves without having to fight, but simply by letting their emotions, the sensations that belong to the delicacy of their souls, to flow freely.

Stefania Miceli, an artist from Bolzano who has always opted for a soft pictorial approach that is dense with an almost magical atmosphere, dedicates her latest production precisely to the female world, entrusting each protagonist with the role of interpreting an emotion, a specific characteristic that expands to become an identifying feature of the gestures and poses in which she portrays her women. Her style tends towards Expressionism while subverting its rules to some extent, as the technique is often mixed, moving between the more traditional oil on canvas and acrylic mixed with plaster subsequently spatulated, to instil in the observer a greater suggestion, a concrete but at the same time impalpable atmosphere with which Miceli envelops the female characters, as if the focal point of each canvas was not only the centre, and therefore the figure, but the entire space around the woman. In this way, the accent is placed on how much the surrounding reality adapts to the inner feeling, how everything that happens around the individual is in some way determined by his way of dealing with existence; the peculiarities of each individual protagonist are enhanced from work to work by the gaze, or by a dress, or even by a specific gesture that identifies the particularity to which the character is attached. The chromatic range is almost always very soft, shaded, in some cases even close to greyscale, because after all, even emotions are often whispered, just as awareness is allowed to emerge in the intimacy of introspection, at the moment when the world is closed off or seems not to observe. That is precisely the instant in which Stefania Miceli lays her gaze on the leaked sensations and imprints them on the canvas, thus giving an overview of those qualities that belong to the feminine soul and that in the contemporary world no longer need to conceal themselves or remain silent. In Determination, a character approach that is indispensable to achieve the result and the set objectives, Stefania Miceli highlights the girl’s eyes, from which a mixture of challenge, self-confidence and pragmatism in pursuing a desire, a dream emerges; what counts is not the details, the artist seems to suggest through the indefiniteness of everything in the painting, but the goal, that achievement which becomes a project to be realised precisely by virtue of the resoluteness needed to impose itself on the surrounding reality.

The thin graphic lines, almost similar to scratches, are a metaphor for the potential obstacles that may hinder the attainment of the result but are not sufficient to stem the protagonist’s will to succeed. In the artwork Loneliness, on the other hand, a condition in which the woman often finds herself as a result of unavoidable choices or in which she takes refuge when she feels the need to find herself, her face is hidden by a large, broadcloth hat, as if the need to distance from everything that surrounds her, and which could distract her from the path of awareness, were the fundamental prerequisite for completing that journey. Loneliness is thus not interpreted with a negative connotation, far from it, on the contrary, it seems to constitute a pleasant, serene phase of great equilibrium from which to choose to put an end to that period. In the painting Transgression on the contrary, Stefania Miceli emphasises irreverence, being outside the box, which sometimes becomes necessary to rebel against circumstances, to affirm one’s independence, to say no to all the rules that limit personal freedom, that require adherence to conventions; a subtle irony transpires in the painter’s gaze, perceptible through the protagonist’s deliberately excessive, exaggerated attitude, in which vices are concentrated to emphasise her decision to be, for a more or less long period, over the top. Tones tending towards sepia accompany the woman’s impertinent pose, focusing attention on her cheeky manner from which her immovability in being what she wants transpires.

So Stefania Miceli places her female characters in front of the observer when they need to express strong and incisive feelings, while she prefers to immortalise them from behind at times when their fragilities might come out, or when they need to reflect, to meditate on themselves; as in Doubts, one of the rare works in which there is a more intense chromatic range, where the girl does not show her face, she seems to be looking at an indefinite and distant point, in front of her and yet apparently unreachable because of the perplexity, the indecision that a particular event, or a choice, has determined. Here, the plaster creates ripples on the canvas, as if to affix a disturbing element, a point of slight rupture between the reality believed, or imagined, and that which instead uncertainty brings to light as possible. The attitude of the body reveals an inner immobility, a paralysis of indecision from which the protagonist can only emerge when she finds the strength to take charge of the situation and make the choice. Stefania Miceli has numerous group exhibitions to her credit and is a member of the Club Arcimboldo association in Bolzano; from 7 to 23 June, the series of artworks dedicated to women will be the focus of her first solo exhibition at the Hotel Sheraton in Via Bruno Buozzi in Bolzano.