Il legame tra espressione artistica e soggetti religiosi risale a molti secoli fa quando la Chiesa era una tra i maggiori committenti nonché mecenate di artisti che hanno lasciato un patrimonio di immenso valore e bellezza, in epoche in cui il messaggio religioso era la base stessa della morale e della vita delle persone; nell’attualità occidentale si è persa la valenza dominante del culto ma in qualche modo molti artisti rimangono affascinati dall’estetica, dall’armonia costituita dalle effigi e dalle immagini religiose al punto di farle diventare il fulcro della loro ricerca pittorica e scultorea pur adattandola a uno stile completamente distaccato dalla figurazione tradizionale. Il protagonista di oggi è in grado di unire un linguaggio informale a quella che è la sacralità delle figure tradizionali visibili nelle chiese, generando uno stile unico e suggestivo.

A partire dalla seconda metà dell’Ottocento si è cominciato a verificare un graduale distacco dell’arte nei confronti della religiosità, di quelle rappresentazioni di episodi biblici che avevano invece costituito la principale produzione pittorica e scultorea degli artisti dei secoli precedenti anche in virtù del grande potere economico del Papato che commissionava grandi opere per adornare cattedrali, basiliche e chiese. Già con il Romanticismo, soprattutto quello inglese, l’attenzione dei maestri come William Turner e John Constable si spostò sui panorami, sulla bellezza e sulla forza della natura come elemento fondamentale della loro osservazione, poi il Realismo cominciò a interessarsi di temi sociali, delle condizioni degli ultimi della società in precedenza ignorati, e infine tutti i movimenti di scomposizione dell’immagine, dall’Impressionismo al Divisionismo, e quelli che invece si rivolgevano all’interiorità del singolo mettendolo al centro della ricerca artistica come l’Espressionismo, segnarono un cammino di allontanamento dalla religiosità destinato ad ampliarsi con le successive avanguardie dei primi anni del Ventesimo secolo. In particolare tutti i movimenti informali, dall’Astrattismo Lirico al De Stijl all’Astrattismo Geometrico e l’Arte Informale tendevano a razionalizzare l’arte, a sottolineare l’indipendenza dell’espressività creativa da qualsiasi forma di individualismo, di sentimentalismo e di legame con la spiritualità; l’arte doveva predominare su tutto, il gesto plastico prescindeva dall’immagine e da qualsiasi riferimento interiore in quanto massima manifestazione di autonomia e superiorità su qualsiasi altra forma di riproduzione dell’immagine o di artigianato. Quell’approccio tanto distaccato era però destinato a evolversi, a cambiare e a tornare verso una connessione con il pensiero filosofico, il concetto o l’interiorità che si concretizzò nell’Arte Concettuale, nell’Espressionismo Astratto e in tutti i movimenti più contemporanei che cercarono di recuperare il contatto con l’emozione del pubblico. Tuttavia il legame con la religione era ancora lontano dall’essere riallacciato, gli artisti della metà degli anni Novanta del Novecento si concentravano prevalentemente sulla psicologia dell’individuo e sull’esistenzialismo, almeno fino alla fine del secolo scorso, quando le grandi migrazioni verso l’occidente indussero gli artisti a esplorare le religioni orientali, quelle del bacino del mediterraneo e di altri paesi lontani. Ed è esattamente su questo inedito approccio filosofico e creativo che si focalizza la produzione artistica di Sandro Bartolacci, di origini italo-greche, che si lascia affascinare dalla bellezza e dalla suggestione di quell’iconografia della chiesa ortodossa a cui è legato in virtù del ramo ellenico della sua famiglia e di cui esplora l’armonia estetica, la suggestione del silenzio e della separazione tra sacro e profano che è stimolato a ricercare nelle sue opere concettuali.

Dunque si addentra in un percorso originale, quello della connessione tra Arte Informale, originariamente più mentale e razionale al punto di distaccarsi da ogni riferimento emotivo, e un’attenzione ai simboli e le icone religiose che riproduce e stilizza nei suoi lavori in cui l’uso della materia, o per meglio dire il plasmarla per assecondarla al suo istinto creativo, è condizione imprescindibile alla rappresentazione.

In qualche modo l’atto creativo di Bartolacci è riconducibile a quella forgia artigiana degli inizi del secolo scorso proprio per l’attenzione al dettaglio, per il bisogno di manualità attraverso cui dare vita a opere dove l’alternanza tra vuoto e pieno, dove la costante presenza del metallo, utilizzato nel suo aspetto naturale oppure ricoperto con colori speciali, è la linea guida dominante che gli consente poi, una volta soddisfatta la sua indole costruttivista, di lasciarsi prendere dal fascino della solennità dei luoghi a cui si ispira.

D’altro canto l’utilizzo di materiali poveri come l’alluminio, il piombo, sempre sotto forma di sottili lastre, e il legno che costituisce la base per le sue pittosculture oppure il predominante delle sculture, lo avvicinano sia alle tesi dell’Arte Povera che anche alla più contemporanea Arte del Riciclo, entrambe orientate a donare nuova vita a oggetti che apparentemente terminerebbero il loro ciclo esistenziale trasformandoli in arte e dando origine a quel percorso virtuoso secondo il quale anche l’ecologia trova giovamento da questo modo differente di smaltire alcuni materiali in realtà molto plasmabili e assecondabili alla creatività.

Oltre alla prerogativa di generare delle serie, in numero massimo di dieci esemplari che presentano variazioni sul tema espressivo principale, Sandro Bartolacci introduce anche in alcune opere le lettere dell’alfabeto miceneo, considerato una forma arcaica della lingua greca, con cui contraddistingue gli elementi, quasi come a sottolineare quanto in fondo sia proprio la vicinanza, la capacità di unirsi a determinare l’armonia generale, la sintonia della condivisione e del riuscire a essere unici anche appartenendo a un gruppo, a un insieme.

Questo sembra essere il senso profondo della serie Esoterico, dove il legno è intagliato e reso concavo all’interno, ciascun cilindro è di altezza e di forma differente sulla sommità, quasi come se quelle sculture tubolari volessero avvicinarsi visivamente alle canne di un organo per poi attrarre l’attenzione verso la loro singolarità che le differisce le une dalle altre, persino nella lettera con cui sono contrassegnate. Il metallo posto all’interno dell’intaglio della parte superiore appare quasi come un’anima musicale e colorata che si erge ed esce dal proprio guscio protettivo, quello del legno, per propagarsi e far percepire la propria voce interiore all’esterno.

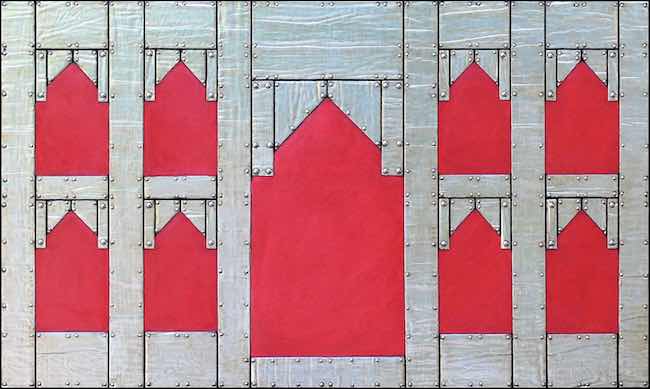

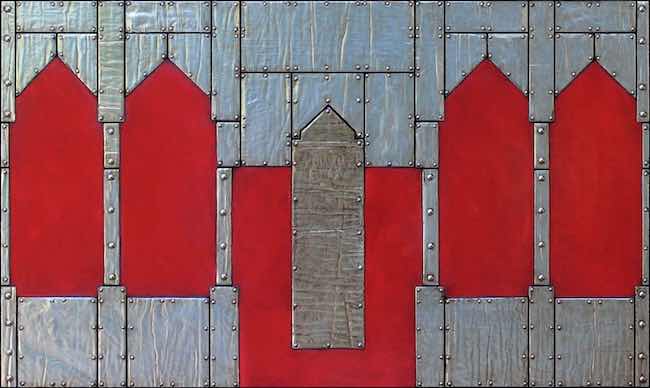

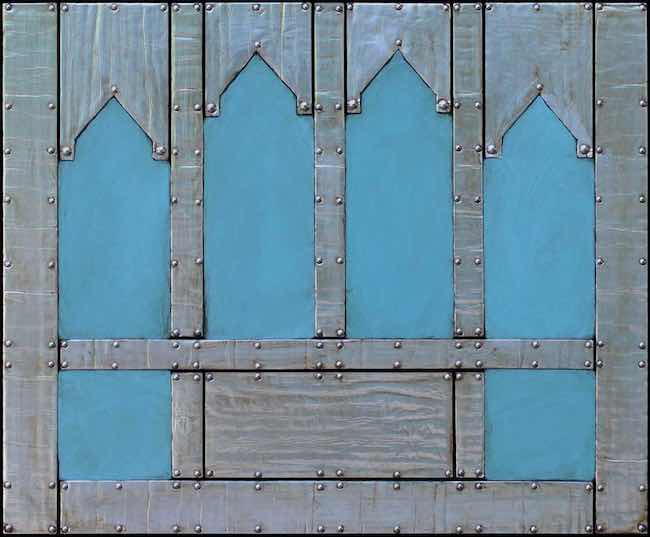

Le opere della serie Iconostasi Primordiale, che danno anche il titolo alla sua prossima mostra personale, sono dei pannelli in legno con applicate lastre di alluminio fermate con piccoli bulloni dello stesso materiale metallico attraverso cui Bartolacci riproduce, nel suo personale stile Concettuale, le pareti divisorie tipiche delle chiese ortodosse in cui vengono raffigurate immagini sacre e che vengono utilizzate per dividere il sacro dal profano, dunque il lato dedicato all’accoglienza dei fedeli e quello oltre il quale il sacerdote celebra la messa; la fastosità di queste pareti, di cui l’artista subisce il fascino estetico, viene essenzializzato e stilizzato in modo da lasciare all’osservatore la possibilità di immaginare il senso di quelle suddivisioni, di ipotizzare la presenza estetica perché ciò che invece è fondamentale per Bartolacci è di andare verso la base del significato, il primordio evocato dal titolo che conduce l’osservatore verso l’inizio della religione, verso l’essenza stessa della vita e della spiritualità, ma soprattutto si concentra sulla sostanza che solo in un secondo momento dovrebbe focalizzarsi sulla forma.

I suoi spazi bifori, trifori o multipli sono lisci nella parte dipinta in rosso, giallo o in azzurro, sebbene quest’ultimo declinato nella tonalità turchese tipica della Grecia, tonalità primarie che tanto importanza avevano ricoperto nelle correnti informali del secolo scorso come il De Stijl, ma poi sono corrugati nelle parti metalliche, quasi come se il profilo esterno fosse il contenitore profano, l’armatura necessaria per esaltare la solennità dell’interno permettendo di meditare su quanto spesso nel vivere contemporaneo si tende a dimenticare l’importanza di proteggere le tradizioni che sono di fatto alla base della stessa dell’evoluzione della società. Sandro Bartolacci ha effettuato un importante percorso nel mondo dell’arte che lo ha visto esporre in mostre personali in Italia e all’estero – Messico, Spagna, Olanda, Inghilterra, Danimarca, Grecia, Francia – e in innumerevoli collettive; alcune sue sculture monumentali sono presenti a Vieste, Roma, Siena, e in provincia di Fermo.

SANDRO BARTOLACCI-CONTATTI

Email: info@sandrobartolacci.it

Sito web: www.sandrobartolacci.it

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/sandro.bartolacci

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/sandrobartolacci/

When matter meets the aesthetics of sacredness in Conceptual Art by Sandro Bartolacci

The link between artistic expression and religious subjects goes back many centuries when the Church was a major commissioner as well as patron of artists who left a heritage of immense value and beauty, in times when the religious message was the very basis of people’s morality and life; in today’s Western world, the dominant value of worship has been lost, but somehow many artists remain fascinated by the aesthetics, the harmony constituted by religious effigies and images to the point of making them the focus of their pictorial and sculptural research while adapting them to a style completely detached from traditional figuration. Today’s protagonist is able to combine an informal language with the sacredness of traditional figures visible in churches, generating a unique and evocative style.

Beginning in the second half of the 19th century, there began to be a gradual detachment of art from religiosity, from those representations of biblical episodes that had instead constituted the main pictorial and sculptural production of artists in previous centuries, also by virtue of the great economic power of the Papacy, which commissioned great works to adorn cathedrals, basilicas and churches. Already with Romanticism, especially English one, the focus of masters such as William Turner and John Constable shifted to panoramas, beauty and the power of nature as the fundamental element of their observation, then Realism began to take an interest in social themes, in the conditions of the previously ignored last of society, and finally all the movements of decomposition of the image, from Impressionism to Divisionism, and those that instead addressed the interiority of the individual by placing it at the centre of artistic research such as Expressionism, marked a path away from religiosity that was destined to expand with the subsequent avant-gardes of the early 20th century. In particular, all the informal movements, from Lyrical Abstractionism to De Stijl to Geometric Abstractionism and Informal Art tended to rationalise art, to emphasise the independence of creative expressiveness from any form of individualism, sentimentalism and connection with spirituality; art had to predominate over everything, the plastic gesture was independent of the image and any inner reference as the ultimate manifestation of autonomy and superiority over any other form of image reproduction or craftsmanship.

That detached approach was, however, destined to evolve, to change and to return towards a connection with philosophical thought, concept or interiority that took concrete form in Conceptual Art, Abstract Expressionism and all the more contemporary movements that sought to recover contact with the public’s emotions. However, the link with religion was still far from being reconnected, the artists of the mid-nineties of the 20th century mainly focused on the psychology of the individual and existentialism, at least until the end of the last century, when the great migrations to the West led artists to explore Eastern religions, those of the Mediterranean basin and other distant countries. And it is precisely on this unprecedented philosophical and creative approach that the artistic production of Sandro Bartolacci, of Italian-Greek origin, focuses. He is fascinated by the beauty and suggestion of the iconography of the Orthodox Church to which he is linked by virtue of the Hellenic branch of his family and of which he explores the aesthetic harmony, the suggestion of silence and the separation between sacred and profane that he is stimulated to seek in his conceptual artworks. So he embarks on an original path, that of the connection between Informal Art, originally more mental and rational to the point of detaching himself from any emotional reference, and a focus on symbols and religious icons that he reproduces and stylises in his works in which the use of matter, or rather the shaping of it to suit his creative instinct, is an essential condition for representation. In some way, Bartolacci’s creative act can be traced back to that artisan forge of the beginning of the last century precisely because of his attention to detail, to the need for manual skill through which he gives life to artworks where the alternation between empty and full, where the constant presence of metal, used in its natural aspect or covered with special colours, is the dominant guideline that then allows him, once his constructivist nature has been satisfied, to let himself be taken by the charm of the solemnity of the places from which he draws his inspiration.

On the other hand, the use of poor materials such as aluminium, lead, always in the form of thin sheets, and wood, which forms the basis for his pictosculptures or predominates in his sculptures, brings him closer to both the theses of Arte Povera and the more contemporary Art of Recycling, both oriented towards giving new life to objects that would apparently end their existential cycle by transforming them into art and giving rise to that virtuous path according to which even ecology finds benefit from this different way of disposing of certain materials that are in reality very malleable and amenable to creativity. In addition to the prerogative of generating series of no more than ten pieces that present variations on the main expressive theme, Sandro Bartolacci also introduces in some works the letters of the Mycenaean alphabet, considered an archaic form of the Greek language, with which he distinguishes the elements, almost as if to emphasise how it is, in the end, proximity, the ability to unite that determines the overall accord, the harmony of sharing and of being able to be unique even while belonging to a group, to a whole. This seems to be the profound sense of the Esoteric series, where the wood is carved and made concave on the inside, each cylinder is of a different height and shape on the top, almost as if those tubular sculptures wanted to visually approach the pipes of an organ and then draw attention to their singularity that differentiates them from one another, even in the letter with which they are marked. The metal placed inside the carving of the upper part appears almost like a musical and colourful soul that rises up and emerges from its protective shell, that of wood, to propagate and make its inner voice heard outside.

The artworks of the Primordial Iconostasis series, which also give the title to his next solo exhibition, are wooden panels with applied aluminium sheets fastened with small bolts of the same metal material through which Bartolacci reproduces, in his personal conceptual style, the dividing walls typical of Orthodox churches in which sacred images are depicted and which are used to divide the sacred from the profane, i.e. the side dedicated to the reception of the faithful and the side beyond which the priest celebrates mass; the sumptuousness of these walls, whose aesthetic charm the artist suffers, is essentialised and stylised in such a way as to leave the observer the possibility of imagining the meaning of those divisions, of hypothesising the aesthetic presence because what is fundamental for Bartolacci is to go towards the basis of meaning, the primordium evoked by the title that leads the observer towards the beginning of religion, towards the very essence of life and spirituality, but above all concentrates on the substance that only later should focus on the form. Its bifori, trifori or multiple spaces are smooth in the part painted in red, yellow or blue, although the latter declined in the turquoise hue typical of Greece, primary tones that were so important in the informal currents of the last century such as De Stijl, but are then corrugated in the metal parts, almost as if the external profile were the profane container, the armour necessary to enhance the solemnity of the interior, allowing us to meditate on how often in contemporary life we tend to forget the importance of protecting traditions that are in fact the basis of society’s evolution. Sandro Bartolacci has made an important career in the world of art that has seen him exhibit in solo shows in Italy and abroad – Mexico, Spain, Holland, England, Denmark, Greece, France – and in countless group shows; some of his monumental sculptures can be found in Vieste, Rome, Siena, and in the province of Fermo.