Molto spesso il mondo interiore, quello profondamente emotivo, ha bisogno di addentrarsi nella dimensione della non forma per far sentire la propria voce in modo più incisivo e intenso di quanto non lo sarebbe se fosse ancorato alle regole e agli schemi esecutivi figurativi; vi sono però artisti i quali hanno la capacità di andare oltre il visibile cercandone l’essenza, dunque interpretando luoghi, più o meno immaginari, trasformandone completamente la definitezza ed entrando in una dimensione differente in cui tutto può essere modificato, ammorbidito e modellato sulla base della sensibilità dello sguardo che su quei paesaggi si posa. L’artista di cui vi parlerò oggi ha un approccio possibilista alla realtà, consapevole che tutto è in fase di modificazione come in un eterno fluire, inducendo l’osservatore a guardare ciò che è davanti a sé in maniera più approfondita, andando al di là della sua forma abituale.

L’Arte Astratta ha attraversato diverse fasi nel corso del Novecento, passando da una nascita più lirica in cui Vassily Kandinsky sottolineava l’importanza di imprimere nell’indefinitezza un contatto con le sensazioni spesso stimolate dall’ascolto della musica, poi attraversando il periodo del rifiuto di ogni soggettivismo e dell’esaltazione della purezza del gesto plastico distaccato da qualunque tipo di ingerenza da parte dell’interiorità dell’esecutore dell’opera, di cui Piet Mondrian fu un pioniere e maggiore rappresentante, e infine ha raggiunto un equilibrio differente, quello dell’urgenza, a volte persino irruenta e veemente, di gridare tutto quel mondo profondo che non riusciva a manifestarsi in un modo diverso se non attraverso la libertà espressiva del confronto con la tela. Quest’ultimo punto di vista generò un vero e proprio movimento artistico rivoluzionario che prese il nome di Espressionismo Astratto, dove l’Astrattismo originario era accompagnato da tutto quel mondo travolgente e a volte sconvolgente che aveva dettato le linee guida di un’altra corrente artistica sovversiva e lontana dalle regole accademiche, l’Espressionismo. Jackson Pollock e i suoi irascibili lottarono a lungo contro la miopia degli ambienti artistici e culturali dell’epoca che rifiutavano di riconoscerli e annoverarli tra le avanguardie americane, e grazie alla loro ostinazione e alla convinzione che l’arte dovesse rispondere ai tre princìpi di libertà, emozione e indefinitezza per poter coinvolgere il pubblico, riuscirono a scrivere una nuova pagina nella storia dell’arte moderna. Le ripercussioni si fecero sentire anche in Europa e molti creativi di quel periodo scelsero di aderire alle linee guida seppur modificandone l’approccio espressivo, per esempio in Italia si generò una modificazione, che prese il nome di Arte Informale, che da un lato rendeva l’esecuzione delle opere meno irruenta e istintiva ma dall’altro spinse artisti come Emilio Vedova, Ennio Morlotti e Giuseppe Santomaso a imprimere nelle loro tele riflessioni più filosofiche, politiche, con una drammaticità sottolineata da colori cupi nel caso dei primi due o più concentrata sulla ricerca dell’equilibrio cromatico nel caso di Santomaso. L’artista pugliese Milena Stilla modifica l’Informale sulla base del proprio sentire, ne schiarisce le tonalità, ampia la gamma cromatica avvalendosi di sfumature che rendono l’immagine finale quasi impalpabile, appartenente a una dimensione mobile, fluttuante, come se volesse porre l’accento sulla consapevolezza eraclitea che tutto scorre, tutto si muove e cambia le forme, sovverte le regole, l’ordine prestabilito e anche il punto di vista.

Racconta i paesaggi osservati attraverso uno stile istintivo ma al tempo stesso meditato, come se la prima intuizione, quella visiva, avesse bisogno di raggiungere una terra di mezzo tra emozione e ragione prima di potersi concretizzare sulla tela, perché l’interiorizzazione che la Stilla fa di ciò che l’occhio vede ha bisogno di una fase riflessiva attraverso cui elaborare e divenire consapevole che in fondo ciò che conta non è il dettaglio, non è il particolare, bensì la coralità del vissuto, la sensazione che quanto visto rimane nella memoria e nell’animo sotto forma di ricordo, di emozione, ed è proprio in virtù di questo che resta immortale. Per accentuare la sensazione di fluidità, di trasformazione delle forme esaminate ed elaborate dal suo sguardo artistico, Milena Stilla si avvale di smalti colorati stratificati attraverso i quali infonde maggiore concretezza alle tonalità utilizzate ma al tempo stesso evidenzia la mescolanza di emozioni e di realtà che inevitabilmente, nella vita come nell’arte, si sovrappongono e perdono la rigidità dei confini visivi per inoltrarsi in un mondo dove tutto è possibile, dove l’evoluzione e la costante modificazione predominano.

La superficie lucida tende a illuminare ancor più le sue sfumature, i contrasti cromatici che a volte contraddistinguono le sue opere tanto quanto invece nella maggior parte dei dipinti lascia prevalere la digradazione e la sfumata fusione con altre tonalità contigue che sembrano ammorbidire l’immagine finale; ma ciò che contribuisce a dare il senso dell’importanza che per la Stilla riveste l’apertura a un punto di vista differente e inedito, sono i titoli in virtù dei quali l’osservatore può intuire il focus di partenza dell’artista prima che il suo sentire intervenisse a modificare i confini reali e li spingesse verso il suo mondo liquido, scorrevole, modificabile, lontano pertanto dal determinismo e dalla rigidità di regole imposte dall’esterno e troppo spesso subite passivamente dall’individuo.

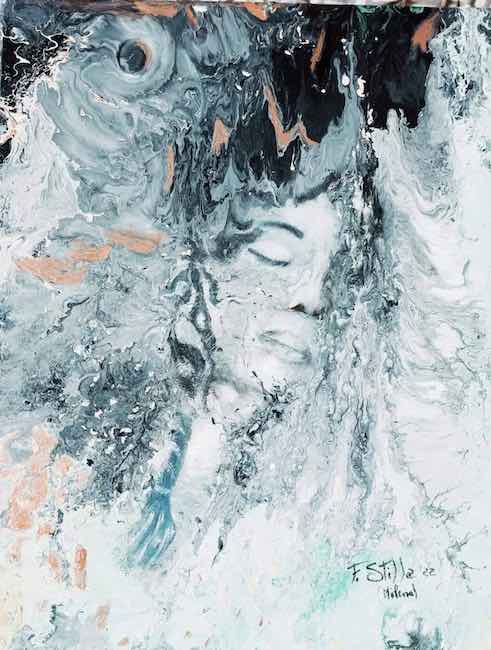

L’opera Figura esotica mostra la dissolvenza del visibile per entrare in un mondo parallelo in cui l’immaginazione sostituisce lo sguardo, e dunque l’osservatore è sollecitato a perdersi inizialmente nell’indefinito prima di scorgere qualcosa che il suo occhio è in grado di riconoscere, di ricondurre a una realtà effettiva. Le tonalità sono chiare, cristalline, illuminate dalla lucentezza dello smalto che sembra voler scorrere sopra l’immagine come se fosse acqua, enfatizzando l’impalpabilità di tutto ciò che circonda il volto come se essa stessa fosse un ricordo riemerso da un cassetto della memoria.

Nella tela Cima di montagne innevate il colore predominante, a dispetto dell’ambientazione evocata nel titolo, è il verde, una tonalità tenue che si mescola ai dettagli scuri delle rocce e al candore che ricopre l’altro lato del dipinto, come se in qualche modo la fotografia nitida scattata dall’occhio della Stilla si fosse sciolta perdendo la definizione e i confini tra i vari elementi che la componevano e poi fosse stata filtrata dall’interpretazione emozionale dell’artista che ne ha stemperato i particolari entrando in una dimensione più interiore.

In Fantasia siderale invece l’artista si distacca completamente dal mondo reale, abbandonandone gli accenni delle altre tele e persino i titoli esplicativi perché la sua esplorazione ha anche bisogno di addentrarsi nella fantasia più pura, nell’intuizione in grado di decifrare l’indecifrabile se solo l’essere umano avesse il coraggio di ascoltarla con maggiore attenzione; le tonalità predominanti sono l’azzurro intenso e il nero, i colori dello spazio, quell’infinito in cui galleggia tutto ciò che l’uomo ha potuto conoscere attraverso i suoi studi e i suoi calcoli, ma che di fatto è a oggi pressoché sconosciuto. Dunque la Stilla si spinge a darne una personale interpretazione descrivendo un luogo non luogo in cui diversi strati di profondità e di oscurità si uniscono affievolendo il senso di vuoto e attenuando il buio proprio in virtù del blu.

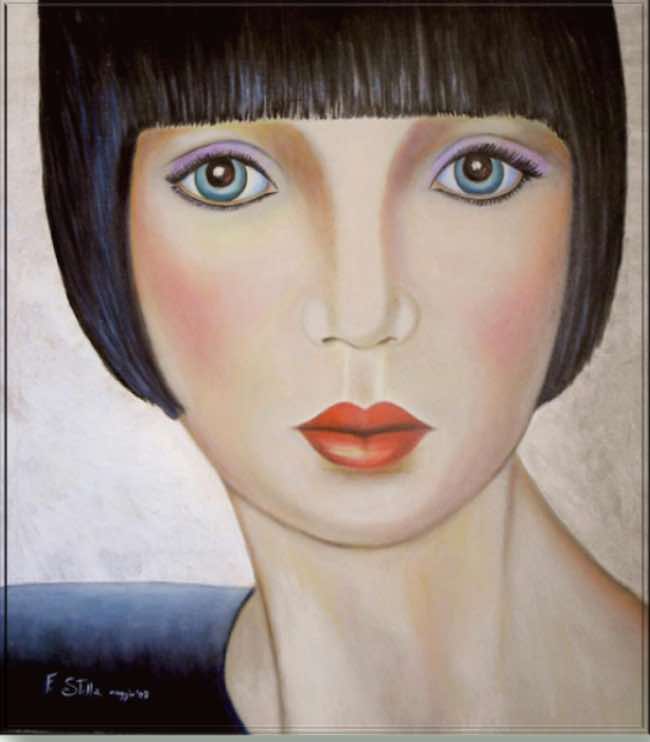

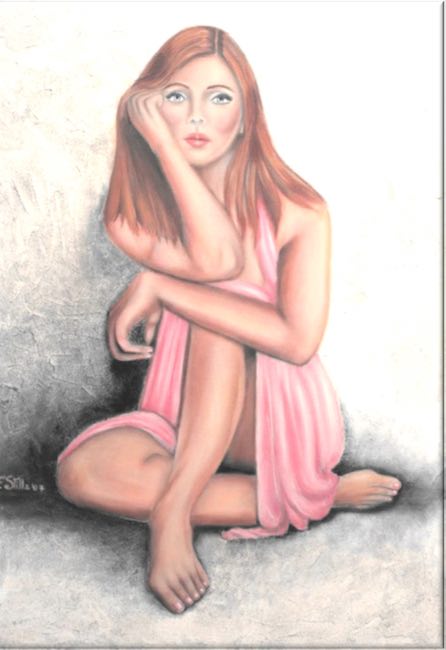

Ma il primo amore di Milena Stilla è la figurazione, la rappresentazione in maniera stilizzata di figure di donna, patinate e raffinate, circondate da sfondi decorativi, graffiati e neutri come se volesse metterle sotto un riflettore artistico dov’è necessario che la loro presenza non sia offuscata da null’altro, dove i loro sguardi, le espressioni, le pose eleganti siano in totale primo piano, rivelando l’ammirazione dell’artista per il genere femminile per la sua bellezza, per i suoi pensieri più nascosti e per i turbamenti che inevitabilmente fanno parte di quel mondo complesso e sfaccettato che è la donna contemporanea.

Milena Stilla nella sua lunga carriera ha partecipato a numerose mostre collettive e personali, ha vinto premi importanti, come il terzo posto al concorso Carnevale Dauno di Manfredonia e il Premio Città di Castello, e riconoscimenti, le sue opere sono state inserite nei più importanti cataloghi d’arte, tra cui l’Annuario d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea “Arte e Collezionismo” e l’Annuario Avanguardie Artistiche edito da Centro Diffusione Arte di Palermo, e fanno parte di collezioni private e pubbliche.

MILENA STILLA-CONTATTI

Email: milena-arte@libero.it

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/milena.stilla.7

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/milenastilla/

Fluid forms and shiny surfaces in the colour digressions of Milena Stilla’s Informal Art

Very often, the interior world, the profoundly emotional one, needs to penetrate the dimension of non-form in order to make its voice heard in a more incisive and intense manner than if it were anchored to figurative rules and schemes of execution. However, there are artists who have the ability to go beyond the visible in search of its essence, thus interpreting places, more or less imaginary, completely transforming their definiteness and entering into a different dimension in which everything can be modified, softened and modelled on the basis of the sensitivity of the gaze that rests on those landscapes. The artist I am going to tell you about today has a possibilist approach to reality, aware that everything is being modified as if in an eternal flow, inducing the observer to look at what is in front of him in a deeper way, going beyond its usual form.

Abstract Art went through various phases during the 20th century, passing from a more lyrical birth in which Vassily Kandinsky emphasised the importance of imprinting in indefiniteness a contact with the sensations often stimulated by listening to music, then passing through the period of the rejection of all subjectivism and the exaltation of the purity of the plastic gesture detached from any kind of interference by the interiority of the artwork’s executor, of which Piet Mondrian was a pioneer and major representative, and finally achieved a different balance, that of the urgency, at times even impetuous and vehement, to shout out all that profound world that could not manifest itself in any other way than through the expressive freedom of confrontation with the canvas.

This last point of view generated a true revolutionary artistic movement that took the name of Abstract Expressionism, where the original Abstractionism was accompanied by all that overwhelming and sometimes shocking world that had dictated the guidelines of another subversive artistic current far from the academic rules, Expressionism. Jackson Pollock and his irascibles struggled for a long time against the short-sightedness of the artistic and cultural circles of the time that refused to recognise and count them among the American avant-gardes, and thanks to their obstinacy and conviction that art had to respond to the three principles of freedom, emotion and indefiniteness in order to involve the public, they succeeded in writing a new page in the history of modern art. The repercussions were also felt in Europe, and many creatives of the period chose to adhere to the guidelines, albeit modifying their expressive approach. In Italy, for example, was generated a modification which took the name of Informal Art, which on the one hand made the execution of artworks less impetuous and instinctive, but on the other pushed artists such as Emilio Vedova, Ennio Morlotti and Giuseppe Santomaso to imprint their canvases with more philosophical, political reflections, with a drama emphasised by sombre colours in the case of the first two or more concentrated on the search for chromatic balance in the case of Santomaso. The Apulian artist Milena Stilla modifies the Informal on the basis of her own feeling, she lightens the tones, broadens the chromatic range using nuances that make the final image almost impalpable, belonging to a mobile, fluctuating dimension, as if she wanted to emphasise the Heraclitean awareness that everything flows, everything moves and changes shapes, subverting the rules, the established order and even the point of view.

She narrates the landscapes she observes through a style that is instinctive but at the same time meditated, as if the first intuition, the visual one, needed to reach a middle ground between emotion and reason before it could materialise on canvas, because the internalisation that Stilla makes of what the eye sees needs a reflexive phase through which to elaborate and become aware that in the end what counts is not the detail, not the particular, but rather the chorality of experience, the sensation that what is seen remains in the memory and soul in the form of memory, of emotion, and it is precisely in virtue of this that it remains immortal. To accentuate the sensation of fluidity, of transformation of the forms examined and elaborated by her artistic eye, Milena Stilla uses layered coloured glazes through which she infuses greater concreteness to the tones used but at the same time highlights the mixture of emotions and realities that inevitably, in life as in art, overlap and lose the rigidity of visual boundaries to enter a world where everything is possible, where evolution and constant modification predominate. The shiny surface tends to further illuminate her nuances, the colour contrasts that sometimes characterise her works as much as in most of them she lets digradation and blending prevail with other contiguous tones that seem to soften the final image; but what contributes to give a sense of the importance that for Stilla has to be opening up to a different and unprecedented point of view are the titles by virtue of which the observer can guess the artist’s starting focus before her feeling intervened to modify the real boundaries and pushed them towards her liquid, flowing, modifiable world, far from the determinism and rigidity of rules imposed from the outside and too often passively suffered by the individual.

The work Exotic Figure shows the fading of the visible to enter a parallel world in which the imagination replaces the gaze, and therefore the observer is urged to initially lose himself in the indefinite before spotting something that his eye is able to recognise, to trace back to an actual reality. The tones are clear, crystalline, illuminated by the brilliance of the enamel that seems to want to flow over the image as if it were water, emphasising the impalpability of everything that surrounds the face as if it were a memory resurfaced from a drawer of memory. In the canvas Top of snow-capped mountains, the predominant colour, in spite of the setting evoked in the title, is green, a soft hue that is mixed with the dark details of the rocks and the whiteness that covers the other side of the painting, as if the sharp photograph taken by Stilla’s eye had somehow dissolved, losing its definition and the boundaries between the various elements that composed it, and then had been filtered by the emotional interpretation of the artist who diluted the details, entering into a more interior dimension. In Sidereal Fantasy, on the other hand, the artist detaches herself completely from the real world, abandoning the hints of the other canvases and even the explanatory titles because her exploration also needs to delve into the purest fantasy, into the intuition capable of deciphering the indecipherable if only human beings had the courage to listen more carefully; the predominant tones are intense blue and black, the colours of space, that infinity in which everything floats that man has been able to know through his studies and calculations, but which is in fact almost unknown to this day. And so Stilla goes so far as to give a personal interpretation of it, describing a non-place in which different layers of depth and darkness come together, softening the sense of emptiness and attenuating the darkness precisely by virtue of the blue. But Milena Stilla’s first love is figuration, the stylised representation of women’s figures, glossy and refined, surrounded by decorative, scratched and neutral backgrounds as if she wanted to put them under an artistic spotlight where their presence is not obscured by anything else, where their glances, expressions, elegant poses are in the foreground, revealing the artist’s admiration for the female gender for its beauty, for its most hidden thoughts and disturbances that are inevitably part of the complex and multifaceted world that is the contemporary woman. In her long career, Milena Stilla has participated in numerous group and solo exhibitions, won prizes and awards, such as third place in the Carnevale Dauno competition in Manfredonia and the Città di Castello Prize, her works have been included in the most important art catalogues, including the Modern and Contemporary Art Yearbook ‘Arte e Collezionismo’ and the Avanguardie Artistiche Yearbook published by Centro Diffusione Arte in Palermo, and are part of private and public collections.