A prescindere dal tipo di approccio che ciascun artista contemporaneo decide di avere, che sia figurativo oppure astratto, ciò che emerge oggi più che in qualsiasi altro periodo storico è la possibilità di mescolare e fondere tecniche appartenenti a settori diversi, più industriali o artigianali rispetto all’arte intesa nel suo senso più tradizionale; questo dà all’autore dell’opera, quanto all’osservatore, la possibilità di trovare un proprio personale equilibrio all’interno della molteplicità espressiva e ai vari stili pittorici esistenti, così come di poter lasciare una propria impronta, definita spesso anche dalla tecnica utilizzata oltre che alla modalità esecutiva. Questa capacità di unire differenti tecniche è ciò che contraddistingue il protagonista di oggi.

Fin dagli esordi del Novecento fu subito chiaro che i confini precedenti, quelli accademici e tradizionali, nell’arte sarebbero stati destinati a essere superati per dare vita a un nuovo orientamento, più sperimentale, più improntato alla ricerca di nuovi materiali, nuove metodologie esecutive, integrando spesso procedimenti appartenenti alle arti minori o all’artigianato e trasformando così l’aspetto finale della tela o della scultura. Già tra la fine del Diciannovesimo e gli inizi del Ventesimo secolo vi fu un movimento artistico che si diffuse in tutta Europa, pur assumendo nomi diversi a seconda del paese di provenienza, che per primo teorizzò la possibilità di fondere conoscenze artigiane e trasformarle in arte; la nuova corrente prese il nome di Arts and Crafts in Inghilterra, Art Nouveau in Francia, Stile Liberty in Italia e Modernismo in Spagna, e ciò che si svelava chiaramente dalle opere degli artisti che vi aderirono era il desiderio di oltrepassare le barriere e far compenetrare l’arte con il decoro, con il vetro, con l’architettura, portando così questo genere creativo nelle case delle persone e nelle strade delle città. Qualche decennio dopo, quando il concettualismo e l’astrazione cominciarono il loro declino, si delinearono correnti artistiche che non solo cercarono di recuperare il contatto con la figurazione, ma tentarono anche di andare verso il grande pubblico per far sì che il messaggio, l’inquietudine e il disadattamento degli artisti che non riuscivano a rientrare nella cerchia della nuova borghesia capace di acquisire in pochi anni un potere d’acquisto che ne determinò la crescita sociale, emergessero e fossero compresi dalle persone che osservavano le loro grandi opere. Il Graffitismo, questo il nome del fenomeno artistico consolidatosi tra gli anni Ottanta e Novanta negli Stati Uniti ma già sperimentato nel Muralismo Messicano, di cui Diego Rivera fu grande esponente, si proponeva di far parlare i muri dei palazzi, i sottopassaggi delle strade ad alto scorrimento, i treni delle metropolitane e qualsiasi altro luogo dove il messaggio dell’autore potesse arrivare forte e chiaro. Oltre a una tecnica espressiva spesso di grande qualità, il Graffitismo, era contraddistinto da scritte, in cui veniva, e tutt’ora viene, nascosto il Tag dell’autore, e anche dalla velocità esecutiva dovuta alla pratica di sporcare i muri, che solo negli anni recenti è stata riconosciuta come forma d’arte e addirittura commissionata da enti locali e statali per decorare e riqualificare interi quartieri delle grandi città. Una delle tecniche più diffuse, insieme agli stencil e alla bomboletta spray, è sempre stata quella dell’aerografo attraverso cui era possibile disegnare linee sottili e definite ma conforme alla velocità necessaria a eseguire un murales.

L’artista altoatesino Guido Coltri, in arte Orso Art, fa suo l’approccio figurativo del Graffitismo ma poi lo plasma e lo adegua alla sua necessità di sentirsi libero di sperimentare e mescolare tecniche pittoriche e grafiche diverse eppure in grado di armonizzarsi per dare vita a opere innovative che da un lato strizzano l’occhio a un’immagine realista ma dall’altro vanno a concretizzarsi su materiali insoliti, diventando testimonianza della necessità di adeguarsi ai tempi contemporanei, anche attraverso i simboli che contraddistinguono la vita attuale.

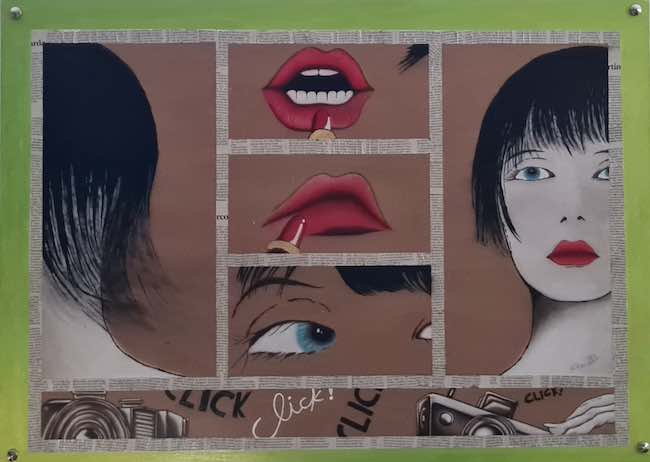

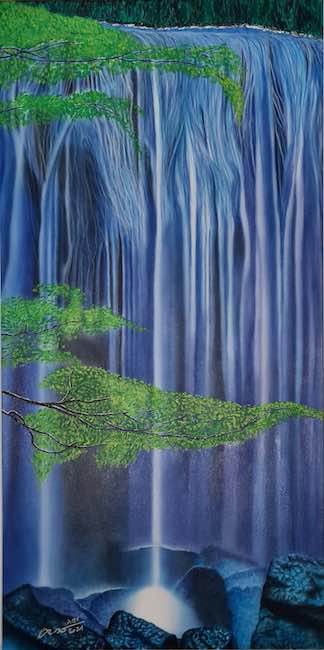

A volte Coltri inserisce nelle sue tele elementi fortemente legati alla Street Art, altre si sposta verso atmosfere più Pop surrealiste, vicine alle pellicole di Tim Burton, in altre ancora mostra un’anima più prevalentemente Pop rendendo protagonisti i divi del cinema italiano o le icone automobilistiche. In ogni caso ciò che emerge in modo chiaro e inequivocabile è la sua necessità di uscire dagli schemi, di non porre limiti alla sua creatività e al desiderio di mescolare materiali e tecniche attraverso cui ha bisogno di esprimersi, di misurare la sua capacità innovativa ed esecutiva. L’approccio pittorico con l’aerografo è uno dei suoi tratti distintivi fin dagli inizi del suo percorso artistico, al punto di approfondirlo grazie ai consigli e agli insegnamenti di uno dei maggiori esponenti di questo stile, il maestro Claudio Mazzi, anche se poco dopo essersi dedicato all’apprendimento e alla personalizzazione della sua capacità di utilizzare il delicato e particolare strumento decide di dare un’impronta personale mescolandolo alla pittura tradizionale, ad acrilico. La funzionalità e la poliedricità dell’aerografo si presta all’utilizzo su molteplici superfici, dall’ardesia al metallo, dalla tela al legno fino essere usato nella Body Art e nella Nail Art, ed è proprio questa libertà che permette a Guido Coltri di dare sfogo al suo bisogno di non fermarsi ai supporti tradizionali bensì di sovvertire l’ordine e pensare fuori dagli schemi, proprio come fecero un secolo fa gli artisti dell’Art Nouveau.

Il dipinto Alfa e Omega è eseguito su Mdf, una fibra derivata dal legno, e mescola la pittura ad aerografo con l’acrilico per dar vita a un’immagine di aspetto gotico, come se la donna narrata fosse protagonista di una commedia dark scritta da Mary Shelley; rappresenta l’inizio e la fine, la possibilità di avere tutto e non avere nulla, di essere libera come le farfalle posate sul collo e sulla testa, oppure intrappolata all’interno delle sue convinzioni e della sua incapacità di prendere in mano la sua vita come testimoniano le cuciture sulle labbra. In qualche modo la ragazza dark rappresenta tutte le donne troppo spesso costrette a scegliere tra un sentimento e il rinunciare a se stesse, tra il desiderio di liberarsi e quello di restare ferme; tuttavia una possibilità c’è, suggerisce l’artista, e viene dal coraggio di quel suo essere ribelle e fuori dagli schemi, almeno nell’aspetto esteriore, che testimonia l’esistenza di un’opzione di cui la protagonista sembra ignara.

Nell’opera Forse domani invece, Guido Coltri si misura con l’insolita superficie dell’ardesia, dove l’aerografo riesce ad apparire persino più sfumato, soffuso, fumoso, infondendo nell’osservazione la sensazione di trovarsi davanti a un film giallo anni Cinquanta in cui il protagonista medita sotto la luce della luna; la scala di grigi sottolinea da un lato il desiderio dell’artista di evocare un ricordo comune, una scena familiare all’immaginario perché appartenente a momenti vissuti nella società recente, dall’altro di evidenziare la suggestione della notte, con il suo silenzio, con le sue ombre e con i suoi misteri.

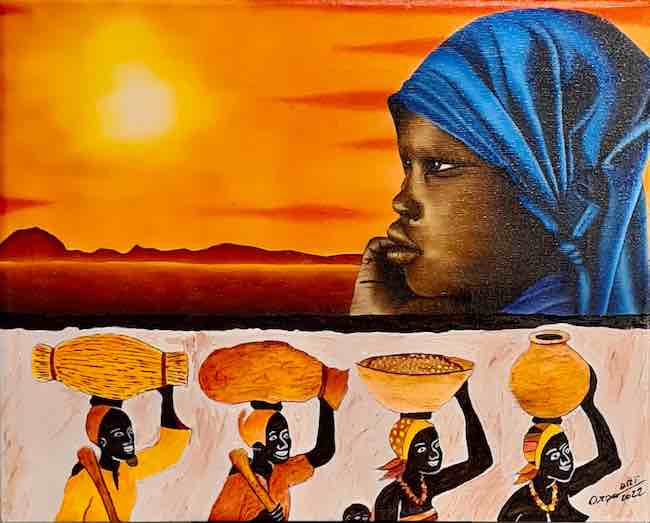

In Pensiero e tradizione Coltri ritrova il colore, la vivacità della narrazione di un paese, l’Africa, pieno di fascino, di semplicità esistenziale, di immediatezza e di spontaneità che emerge sia dalle donne in basso sulla tela e immerse nei loro compiti quotidiani, e sia dall’espressione intensa della ragazza in primo piano che sembra scrutare l’orizzonte per domandarsi dove la porterà il suo futuro; gioca sull’equilibrio tra il sogno di una modernità possibile e tutto ciò che appartiene alla cultura delle popolazioni di quel continente che vivono basandosi sul patrimonio di conoscenza e di saggezza che gli anziani tramandano verbalmente ai giovani.

Ma è in Quando c’era lei… la sorpresa più grande, l’anima più Pop Art di Guido Coltri, un’opera in cui immortala quattro tra i maggiori attori italiani degli anni tra il Cinquanta e il Settanta, Sofia Loren, Totò, Ugo Tognazzi, Alberto Sordi, riproducendo i loro volti, sempre utilizzando l’aerografo in questo caso molto definito, ma ciò che stupisce di più è la superficie su cui realizza il dipinto, il musetto di una vecchia Fiat, simbolo del benessere economico e del progresso di quegli anni lontani.

Guido Coltri si è affermato nel corso del tempo proprio in virtù del suo sapiente utilizzo dell’aerografo, e sta effettuando un percorso interessante nel mondo dell’arte italiano e internazionale; una sua opera è esposta all’ingresso principale dell’Ospedale di Bolzano e un’altra è diventata da poco parte del patrimonio dell’Istituto Salesiano della città. È socio del Club Arcimboldo di Bolzano.

GUIDO COLTRI-CONTATTI

Email: orsolupo77@gmail.com

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/guido.coltri

https://www.facebook.com/OrsoArt

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/orso_art/

Unseen surfaces and innovative materials as essential prerequisites of Guido Coltri Orso Art’s creative eclecticism

Regardless of the type of approach that each contemporary artist decides to take, be it figurative or abstract, what emerges today more than in any other historical period is the possibility of mixing and blending techniques belonging to different sectors, more industrial or artisanal than art intended in its more traditional sense; this gives the author of the work, as much as the observer, the possibility of finding their own personal balance within the multiplicity of expression and the various existing painting styles, as well as of being able to leave their own imprint, often defined by the technique used as well as the method of execution. This ability to combine different techniques is what distinguishes today’s protagonist.

From the very beginning of the 20th century, it was immediately clear that the previous boundaries, the academic and traditional ones, in art were destined to be overcome in order to give rise to a new orientation, more experimental, more focused on the search for new materials, new methods of execution, often integrating processes belonging to the minor arts or crafts and thus transforming the final appearance of the canvas or sculpture. As early as the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century, there was an artistic movement that spread throughout Europe, although it took on different names depending on the country of origin, which first theorised the possibility of fusing craft knowledge and transforming it into art; the new current took the name Arts and Crafts in England, Art Nouveau in France, Stile Liberty in Italy and Modernism in Spain, and what was clearly revealed by the works of the artists who adhered to it was the desire to break through barriers and make art interpenetrate with decoration, with glass, with architecture, thus bringing this creative genre into people’s homes and city streets. A few decades later, when conceptualism and abstraction began their decline, emerged artistic currents that not only tried to regain contact with figuration, but also attempted to reach out to the general public so that the message, the restlessness and maladjustment of artists who could not fit into the circle of the new bourgeoisie that was able to acquire a purchasing power in a few years that determined their social growth, would emerge and be understood by the people who observed their great artworks. Graffitism, this is the name of the artistic phenomenon that consolidated between the 1980s and 1990s in the United States but had already been experimented in Mexican Muralism, of which Diego Rivera was a great exponent, aimed to make the walls of buildings, the subways of highways, underground trains and any other place where the author’s message could arrive loud and clear.

In addition to an expressive technique often of great quality, Graffitism was characterised by writings in which the author’s tag was, and still is, hidden, and also by the speed of execution due to the practice of dirtying walls, which only in recent years has been recognised as an art form and even commissioned by local and state authorities to decorate and redevelop entire neighbourhoods of large cities. One of the most popular techniques, along with stencils and spray cans, has always been the airbrush, through which it was possible to draw thin, defined lines that conformed to the speed required to execute a mural. The South Tyrolean artist Guido Coltri, aka Orso Art, makes the figurative approach of Graffitism his own, but then moulds and adapts it to his need to feel free to experiment and mix different painting and graphic techniques that are nevertheless able to harmonise to give life to innovative artworks that on the one hand wink at a realistic image but on the other hand take shape on unusual materials, becoming evidence of the need to adapt to contemporary times, also through the symbols that characterise current life. At times Coltri inserts elements strongly linked to Street Art into his canvases, at others he moves towards more Pop surrealist atmospheres, close to Tim Burton’s films, and at others he shows a more predominantly Pop soul by making protagonsts Italian film stars or car icons. In any case, what emerges clearly and unequivocally is his need to break out of the mould, to set no limits to his creativity and his desire to mix materials and techniques through which he needs to express himself, to measure his innovative and executive capacity. The pictorial approach with the airbrush has been one of his hallmarks since the beginning of his artistic career, to the point of deepening it thanks to the advice and teachings of one of the greatest exponents of this style, master Claudio Mazzi. However, shortly after he dedicated himself to learning and customising his ability to use this delicate and special tool, he decided to give it a personal touch by mixing it with traditional, acrylic painting. The functionality and versatility of the airbrush lends itself to use on multiple surfaces, from slate to metal, from canvas to wood, even being used in Body Art and Nail Art, and it is precisely this freedom that allows Guido Coltri to give vent to his need not to stop at traditional media but to subvert order and think outside the box, just as the artists of Art Nouveau did a century ago.

The painting Alpha and Omega is executed on Mdf, a fibre derived from wood, and mixes airbrush paint with acrylic to create a Gothic-looking image, as if the narrated woman were the protagonist of a dark comedy written by Mary Shelley; she represents the beginning and the end, the possibility of having everything and having nothing, of being free like the butterflies on her neck and head, or trapped within her convictions and her inability to take charge of her life as evidenced by the stitching on her lips. In some way, the dark girl represents all women who are too often forced to choose between a feeling and giving up on themselves, between the desire to free themselves and the desire to stay put; however, there is a possibility, the artist suggests, and it comes from the courage of her rebellious and unconventional being, at least in her outward appearance, which testifies to the existence of an option of which the protagonist seems unaware. In the artwork Maybe Tomorrow, on the other hand, Guido Coltri measures himself with the unusual surface of slate, where the airbrush succeeds in appearing even more nuanced, suffused, smoky, instilling in the observer the sensation of being in front of a 1950s crime film in which the protagonist meditates under the moonlight; the greyscale emphasises, on the one hand, the artist’s desire to evoke a common memory, a scene familiar to the imagination because it belongs to moments experienced in recent society, and on the other, to highlight the suggestion of the night, with its silence, its shadows and its mysteries.

In Thought and Tradition Coltri rediscovers the colour, the liveliness of the narrative of a country, Africa, full of charm, existential simplicity, immediacy and spontaneity that emerges both from the women at the bottom of the canvas and immersed in their daily tasks, and from the intense expression of the girl in the foreground who seems to be scanning the horizon wondering where her future will take her; plays on the balance between the dream of a possible modernity and everything that belongs to the culture of the people of that continent who live based on the heritage of knowledge and wisdom that the elderly pass on verbally to the young. But it is in When she was there… that is the biggest surprise, the most Pop Art soul of Guido Coltri, an artwork in which he immortalises four of the greatest Italian actors of the years between the 1950s and the 1970s, Sofia Loren, Totò, Ugo Tognazzi, Alberto Sordi, reproducing their faces, again using the airbrush in this case very clearly defined, but what is most surprising is the surface on which he creates the painting, the nose of an old Fiat, a symbol of the economic prosperity and progress of those distant years. Guido Coltri has established himself in the course of time precisely because of his skilful use of the airbrush, and he is making an interesting career in the Italian and international art world; one of his works is exhibited at the main entrance of the Bolzano Hospital and another has recently become part of the heritage of the Salesian Institute in the city. He is a member of the Club Arcimboldo in Bolzano.