Il privilegio degli artisti contemporanei non è solo quello di aver potuto osservare e studiare la dinamicità creativa dei maestri del passato più recente, con le loro singolarità, le distorsioni, il distacco dall’osservato, bensì anche quello di poter mescolare stili originariamente separati e distanti tra loro per dare vita a un inedito linguaggio attraverso il quale lasciarsi trasportare senza regole scegliendo la base irrinunciabile della libertà. L’artista di cui vi racconterò oggi permette al proprio istinto, al proprio impeto espressivo di dettare le regole attraverso cui si delinea un modo assolutamente personale e particolare di dare voce alla creatività.

L’inizio del Ventesimo secolo si è dimostrato uno dei periodi più vivaci e inquieti dell’intera storia dell’arte, aprendo le porte a tutti quei radicali cambiamenti nel modo di intendere l’espressione creativa e anche nel dare spazio a linguaggi figurativi che mai prima di allora erano stati elaborati né presi in considerazione. Il Futurismo aveva ristrutturato la bellezza artistica frammentando l’immagine per infondere nell’osservatore il senso di dinamicità e di velocità che apparteneva a quei primi anni del secolo in cui le innovazioni e le scoperte tecnologiche cominciavano a cambiare il modo di vivere delle persone; poco dopo il Cubismo fece proprie le medesime tematiche di scomposizione per elaborare però uno stile più umanista, più dedicato allo studio dell’essere umano nelle sue sfaccettature, nelle sue molteplici angolazioni che necessitavano dunque di essere suddivise, osservate nella loro complessità senza dover andare a cercare la prospettiva, la profondità bensì inserendo nella tela in maniera piatta e simultanea tutti gli elementi della realtà protagonista del momento creativo. Pablo Picasso seppe infondere incredibile impatto espressivo nelle sue opere più note, Guernica e Le demoiselles d’Avignon, sottolineando quanto la bellezza e l’armonia esteriore non fossero fondamentali per un percorso artistico contro ogni schema precedente e tuttavia in grado di emozionare l’osservatore. Parimenti interessati all’interiorità, alla mente e alle pulsioni umane, furono gli artisti aderenti al Surrealismo in cui l’immagine si accordava all’universo irreale e onirico delle opere di Salvador Dalì, in cui la perfezione esecutiva era distorta dalle deviazioni della mente inconscia, e di quelle di Max Ernst, sia pittoriche che scultoree, dove la stilizzazione degli scenari improbabili e inquietanti era perfettamente in grado di condurre l’osservatore nel suo mondo irrequieto e pieno di personaggi a metà tra l’umano e il soprannaturale. Più avanti nacque in Francia, grazie al pittore Jean Dubuffet, proprio in luoghi in cui le inquietudini della mente venivano curati e dunque l’atto esecutivo era immediato, spontaneo, senza conoscenza stilistica, questo almeno nell’inizio del percorso del movimento, l’Art Brut, letteralmente arte grezza, che si avvaleva di materiali poveri, raccolti all’interno dei centri psichiatrici, e soprattutto nei dipinti e nelle sculture venivano rappresentate illusioni, sogni, incubi, fantasie elaborate e manifestate su tela.

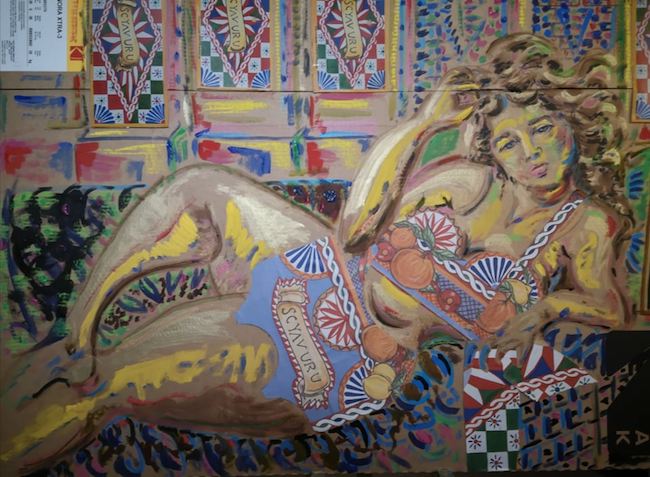

L’artista bolognese Letizia Cucciarelli si avvicina all’Art Brut, pur essendo il suo un percorso tutt’altro che mancante di approfondimento e di conoscenza anzi spesso si ispira proprio all’arte dei maestri del passato e in particolar modo dei surrealisti e dei cubisti, nel lasciare che la sua creatività si manifesti in modo libero, inconsapevole a volte del risultato finale, che le sue sensazioni fluiscano senza alcuna guida, senza alcuna strada tracciata dalla mente, trasformando l’atto pittorico e scultoreo in una vera e propria catarsi, un processo di identificazione con i materiali usati che sembrano guidare la mano, ormai solo esecutrice di ciò che l’impulso creativo detta. Malgrado l’assenza di frequentazione di un’Accademia o di studi specifici, la Cucciarelli mostra una spiccata personalità artistica in grado di scegliere un percorso individuale e libero da qualsiasi dogma preesistente, è questo che la avvicina all’Art Brut, quella necessità di rappresentare le sue personali visioni, quell’inconsapevolezza e spontaneità che appartengono a chi è in grado di distaccarsi dal percorso visibile, dal concetto di attenersi a regole figurative generando pensieri e fantasie che lo sguardo non conosce.

La sua anima cerca una costante sperimentazione, si spinge all’utilizzo di materiali non collegabili all’arte, all’introduzione nelle sue sculture di oggetti di uso comune come perline, bottoni, legni, pietre, pezzi di ferro, cocci di vaso, braccialetti, piattini d’argento, tessuti, conchiglie, mentre i colori non vengono scelti dall’artista bensì sembra che si auto selezionino, sembra che siano essi stessi a chiedere di essere utilizzati mentre la Cucciarelli si lascia guidare da un impulso espressivo indefinibile quanto intenso. Non solo l’impeto creativo ma anche i suoi numerosi viaggi influenzano quella poliedricità creativa che la contraddistingue, divenendo spunto di riflessione, di approfondimento e di narrazione delle molteplici sfaccettature di un naturale tendere verso la liberazione delle energie espressive che hanno bisogno di mostrarsi.

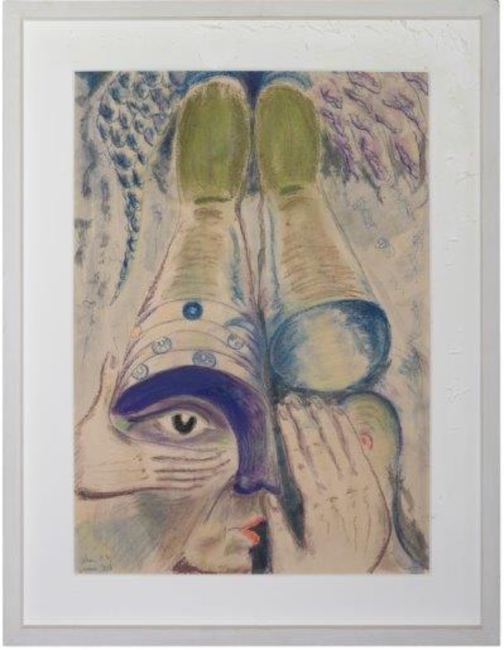

Nella scultura Pablo et moi, la Cucciarelli si ispira al maestro del Cubismo per elaborare una propria rivisitazione in cui mescola la multifocale osservazione dei volti e dei personaggi a un suo approccio più morbido, meno spigoloso ma non per questo meno dissacrante di quelli che sono gli schemi estetici, prospettici e compositivi più classici; la deformazione dei volti e dei corpi presente nelle due opere ricorda le distorsioni pittoriche di Jean Dubuffet. L’alterazione delle espressioni dei soggetti raffigurati infonde nell’osservatore un senso di disorientamento, rappresenta angoscia nel vedere ciò che è intorno, i limiti e le crudeltà a cui l’uomo di tutti i tempi è sempre stato chiamato a vivere, a vedere, senza potersi difendere, senza potersi proteggere da quelle circostanze.

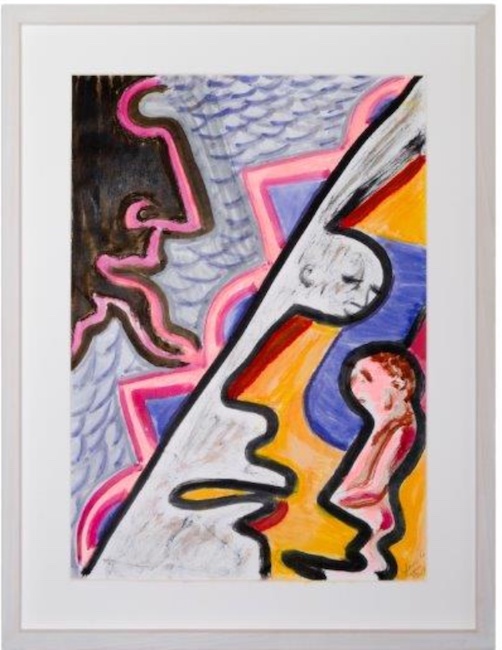

Anche in The human race l’attenzione della Cucciarelli è rivolta alle espressioni, agli sguardi che quei profili umani non possono fare a meno di riservare a quanto li circonda, restandone sbigottiti o semplicemente assuefatti, come se in qualche modo l’abitudine agli eventi diventasse un modo per difendersi ma anche per corazzarsi contro il susseguirsi di fatti e accadimenti.

E ancora nella scultura Quando la passione svanisce l’artista gioca con l’illusione ottica dell’uno che può essere parte di una coppia se si considera il profilo e un’unica persona se si opta per l’approccio visivo frontale, dando un significato particolare alla scultura, significato che si lega al titolo e che svela quanto dopo molto tempo insieme a qualcuno, dopo aver condiviso emozioni e sensazioni che quasi avevano condotto le due parti a considerarsi un solo Uno, può accadere invece di sentirsi lontani, due unità distinte e separate che, a volte, non riescono a trovare un nuovo modo per restare insieme. I due volti sono uno di fronte all’altro eppure sembrano guardare altrove, come se il loro cammino comune fosse irrimediabilmente compromesso da una crescita verso direzioni differenti.

L’impulso di lasciarsi andare in maniera istintiva all’estro creativo si trasforma in studio nel caso di altre sculture, quelle in cui l’approfondimento è fondamentale a realizzare un progetto denso di significati, come la serie dei Papi a cui appartiene l’opera Papa Innocenzo III in cui emerge un profondo simbolismo attraverso il quale la Cucciarelli dà la propria versione e interpretazione dei grandi protagonisti della Chiesa cristiana e della fede; la sua ricerca è accurata e si spinge anche ai Templari e alle tradizioni storico-religiose che avvolgono i secoli precedenti. In quest’opera la linea è marcata, definita, realista ma anche surrealista considerando che al posto degli occhi del Papa l’artista pone delle croci. La serie dedicata ai Papi, dodici sculture di pontefici, quattro di Santi e la Tavola di Blake sono stati esposti a Pieve di Palaia all’evento di commemorazione per i settecento anni dalla morte di Dante.

Letizia Cucciarelli è attratta dall’arte fin da bambina ma poi decide di lasciarla da parte per abbracciare un percorso professionale come commercialista e solo negli ultimi anni è tornata a dedicarsi alla sua antica passione per l’espressione creativa; dal 2017 a oggi ha partecipato a moltissime mostre collettive in Italia e all’estero, tra le più importanti una personale organizzata a Santo Domingo presso il Centro Culturale di Banreservas a cui ha preso parte l’Ambasciatore italiano e la collettiva I cinque sensi presso l’Istituto di Cultura Italiana di Stoccolma. Le sue opere sono inserite in diversi importanti cataloghi nazionali.

LETIZIA CUCCIARELLI-CONTATTI

Email: info@dadaletizia.com

Sito web: https://www.dadaletizia.com

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/letizia.cucciarelli

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/letiziacucciarelli/

Letizia Cucciarelli’s artistic expression between visions and creative contaminations

The privilege of contemporary artists is not only that of having been able to observe and study the creative dynamism of the masters of the most recent past, with their singularities, distortions and detachment from the observed, but also that of being able to mix styles that were originally separate and distant from each other to give life to a new language through which they can let themselves be transported without rules, choosing the indispensable basis of freedom. The artist I am going to tell you about today allows his instinct, his expressive impetus to dictate the rules through which she outlines an absolutely personal and particular way of giving voice to creativity.

The beginning of the twentieth century proved to be one of the most lively and restless periods in the entire history of art, opening the door to all those radical changes in the way of understanding creative expression and also in giving space to figurative languages that had never before been elaborated or taken into consideration. Futurism had restructured artistic beauty by fragmenting the image in order to instil in the viewer the sense of dynamism and speed that belonged to those early years of the century when technological innovations and discoveries were beginning to change the way people lived; shortly afterwards, Cubism took up the same themes of decomposition to develop a more humanist style, more dedicated to the study of the human being in all his facets, in his multiple angles that needed to be divided up, observed in their complexity without having to look for perspective, depth, but rather by inserting into the canvas in a flat and simultaneous manner all the elements of the reality that was the protagonist of the creative moment. Pablo Picasso was able to infuse incredible expressive impact into his best-known paintings, Guernica and The Demoiselles d’Avignon, emphasising that external beauty and harmony were not fundamental to an artistic path that went against all previous schemes and yet was capable of moving the observer.

Equally interested in the interiority, the mind and human impulses, were the artists who adhered to Surrealism in which the image matched the unreal and dreamlike universe of the artworks of Salvador Dali, in which the perfection of execution was distorted by the deviations of the unconscious mind, and those of Max Ernst, both pictorial and sculptural, where the stylisation of improbable and disturbing scenarios was perfectly capable of leading the observer into his restless world full of characters somewhere between the human and the supernatural. Later was born in France, thanks to the painter Jean Dubuffet, in places where the restlessness of the mind was treated and therefore the act of execution was immediate, spontaneous, without stylistic knowledge, this at least in the beginning of the movement, Brut Art, literally raw art, which used poor materials, collected in psychiatric centres, and especially in paintings and sculptures were represented illusions, dreams, nightmares, fantasies elaborated and manifested on canvas. The Bolognese artist Letizia Cucciarelli approaches Brut Art, although her path is far from lacking in depth and knowledge indeed, she often draws inspiration from the art of the masters of the past, particularly the Surrealists and Cubists, in allowing her creativity to manifest itself freely, sometimes unaware of the final result, allowing her sensations to flow without any guidance, without any road mapped out by the mind, transforming the act of painting and sculpture into a true catharsis, a process of identification with the materials used that seem to guide the hand, which is now only the executor of what the creative impulse dictates.

Despite not attending an academy or specific studies, Cucciarelli shows a strong artistic personality capable of choosing an individual path, free from any pre-existing dogma. This is what brings her closer to Brut Art, the need to represent her personal visions, that unawareness and spontaneity that belong to those who are able to detach themselves from the visible path, from the concept of following figurative rules, generating thoughts and fantasies that the eye does not know. Her soul seeks constant experimentation, she pushes herself to the use of materials that cannot be linked to art, to the introduction into her sculptures of everyday objects such as beads, buttons, wood, stones, pieces of iron, potsherds, bracelets, silver saucers, fabrics, shells, while the colours are not chosen by the artist but seem to be self-selected, they seem to be asking to be used, while Cucciarelli lets herself be guided by an expressive impulse that is as indefinable as it is intense. Not only her creative impetus but also her numerous journeys influence the creative versatility that distinguishes her, becoming a starting point for reflection, investigation and narration of the many facets of a natural tendency towards the liberation of expressive energies that need to be shown. In the sculpture Pablo et moi, Cucciarelli is inspired by the master of Cubism to elaborate her own reinterpretation in which she mixes the multifocal observation of faces and characters with her softer, less angular but no less desecrating approach to the more classic aesthetic, perspective and compositional schemes; the deformation of faces and bodies in the two sculptures recalls the pictorial distortions of Jean Dubuffet. The tampering of the expressions of the subjects depicted instils in the observer a sense of disorientation, representing anguish in seeing what is around, the limits and cruelties to which mankind of all times has always been called upon to live, to see, without being able to defend itself, without being able to protect itself from those circumstances.

In The Human Race, too, Cucciarelli’s attention is focused on the expressions, the looks that those human profiles cannot help but reserve for what surrounds them, remaining astonished or simply addicted, as if in some way the habit of events became a way of defending themselves but also of armouring themselves against the succession of facts and events. In the sculpture Quando la passione svanisce (When passion fades away), the artist plays with the optical illusion of the one, which can be part of a couple if one considers the profile and a single person if one opts for the frontal visual approach, giving a particular meaning to the sculpture, a meaning that ties in with the title and reveals how after a long time together with someone, after sharing emotions and sensations that almost led the two parties to consider themselves as one, it can happen instead that one feels afar, two distinct and separate units that sometimes cannot find a new way to stay together. The two faces are one in front of the other but yet they seem to be looking elsewhere, as if their common path is hopelessly compromised by growth in different directions. The impulse to let go instinctively to creative inspiration is transformed into study in the case of other sculptures, those in which deepening is fundamental to realise a project full of meanings, such as the series of Popes to which the artwork Pope Innocent III belongs, in which emerges a profound symbolism through which Cucciarelli gives her own version and interpretation of the great protagonists of the Christian Church and faith; her research is meticolous and also goes up to the Templars and the historical-religious traditions surrounding the previous centuries. In this sculpture the line is marked, defined, realistic but also surrealist, considering that the artist places crosses in place of the Pope’s eyes. The series dedicated to the Popes, twelve sculptures of popes, four of saints and Blake’s Table were exhibited in Pieve di Palaia at the commemoration event for the seven hundredth anniversary of Dante’s death. Letizia Cucciarelli has been attracted to art since she was a child but then decided to leave it aside to embrace a professional career as an accountant and only in recent years she has returned to devote herself to her ancient passion for creative expression; from 2017 to the present day she has taken part in many group exhibitions in Italy and abroad, among the most important a solo exhibition organised in Santo Domingo at the Banreservas Cultural Centre in which the Italian Ambassador took part and the group exhibition I cinque sensi at the Italian Cultural Institute in Stockholm. Her artworks are included in several important national catalogues.