L’approccio pittorico di ciascun creativo si esprime attraverso il filtro dell’interiorità, del modo di osservare tutto ciò che ruota intorno ma anche della capacità di approfondimento e dell’andare oltre la patina superficiale della contemporaneità e delle sensazioni che appartengono al punto di osservazione da cui ciascun artista parte; in alcuni casi la ricerca si spinge talmente tanto in profondità da aver bisogno di fumosità e oscurità per riuscire a tendere poi, in un secondo momento, verso la luce, metafora della conoscenza di sé e di ciò che è esterno a sé. L’artista di cui vi racconterò oggi affronta il mondo del buio, della penombra, intesi come spazio silenzioso dentro cui perdersi per poi essere in grado di trovare il senso di un’emozione uscendo da quella rete di certezze che troppo spesso divengono ostacoli a una più libera interpretazione del visto e del vissuto.

Il movimento pittorico nato negli Stati Uniti intorno alla metà degli anni Cinquanta del Novecento, denominato Espressionismo Astratto, mostrò fin da subito una delle sue linee guida fondamentali e cioè la libertà espressiva che non poteva, e non doveva, essere condizionata da regole e schemi che non fossero quelli del sentire dell’autore dell’opera; ciò che invece non doveva mancare era l’emozione raccontata, affrontata, manifestata sulla base dell’indole del creativo e interpretata secondo il proprio personale punto di vista. Va da sé che la base astratta fosse così assecondata al puro istinto, a volte più vivace o travolgente, altro invece più riflessivo e meditativo, pur avendo il comun denominatore di stimolare una reazione nell’osservatore, che fosse coinvolgimento, scossa emozionale o spunto di meditazione. Dunque all’impeto pittorico di Jackson Pollock e di Lee Krasner, dove il Dripping e il gesto per attuarlo divenivano non solo parte stessa del quadro ma anche un modo per sottintendere quanto ogni singola sensazione avesse una sua propria personalità espressa attraverso differenti e molteplici colori, rispondeva il temperamento più calmo ma sempre orientato all’intensità della gamma cromatica di Mark Rothko e di Barnett Newman, tendente quest’ultimo alla monocromia del Minimalismo; la solarità tonale di Hans Hofmann e di Morris Louis, dove non vi erano limiti all’accostamento dei colori, come se la loro presenza fosse l’unico dialogo possibile con il fruitore, si contrapponeva alla pittura segnica contraddistinta da bicromie intense e incisive di Franz Kline e Robert Motherwell per cui la sensazione doveva essere privata di ogni abbellimento distraente. Tra loro vi erano però anche artisti più intimisti, più orientati a cercare di lasciar emergere i limiti e i condizionamenti dell’essere umano nella società dell’epoca, in cui la pittura assumeva tonalità terrose, fumose, proprio per indicare la quotidianità spesso appiattente; le opere di questi artisti erano accompagnate da graffi, da linee sottili solcanti le superfici proprio per sottolineare quanto fosse necessario scavare e andare oltre per riuscire a comprendere il senso del tutto. In quest’ultimo sottogruppo di esponenti dell’Espressionismo Astratto vi erano William Congdon, dove le crepe del colore lasciavano emergere sottile e stilizzata figurazione, e Mark Tobey in cui i segni, le scritte, le line sembravano coprire la realtà, in ogni caso contraddistinta da fondi scuri, bui come lo è la notte della conoscenza quando non riesce a immergersi al di là di quelle apparenti barriere.

Lo stile pittorico dell’artista Helena Manzan, di origini brasiliane e venete, residente in Italia ormai da molti anni, sembra costituire una sintesi tra i graffi di Congdon, dove l’elemento materico contribuisce a dare rilievo ad alcune parti della composizione, e le linee di Tobey, mentre di entrambi eredita gli sfondi a volte più cupi, altre più chiari ma sempre come se il processo di apprendimento, di scoperta del significato delle sue tele, non volesse rivelare troppo, rimanesse costantemente sussurrato, accennato per indurre l’osservatore alla riflessione, a un percorso di comprensione profondo, esattamente come introspettivo è il suo nell’atto creativo. Ciò che emerge in maniera chiara dalle opere di Helena Manzan è la consapevolezza di quanto tutto sia coperto da una fitta rete di apparenza, che lei racconta sotto forma di reticolo il quale di fatto rappresenta l’incapacità dell’individuo contemporaneo di soffermarsi su cosa vi sia oltre, di cercare di osservare in maniera più attenta cosa vi sia dietro le finte certezze e le superfici che molti si convincano siano la verità.

Helena Manzan sembra invitare l’osservatore a non temere di affrontare anche il buio perché di fatto tutto, ogni cosa, ogni percorso, sono necessari a effettuare quell’avvicinamento alla luce, intesa come coscienza di sé e di tutto ciò che ruota intorno all’essere umano costituendone la quotidianità; è solo a seguito della scelta coraggiosa di entrare in quella rete di illusioni che può compiersi l’evoluzione, una maggiore presa di coscienza trovando così la propria luce, quella che saprà dissolvere le ombre, le incertezze, le paure.

Le opere della Manzan costituiscono dunque una vera e propria ricerca per sottolineare la quale si avvale di materiali inediti, dando vita a una tecnica mista appena percettibile ma che amplia il senso finale del dipinto divenendone completamento perché è solo attraverso la capacità visionaria di trovare soluzioni impensate che si può tendere verso una conoscenza che non è quella comune, spesso peraltro ingannevole, bensì quella personale, singola e forse per questo maggiormente reale. Cenere, fieno, fiori secchi, smalti, si mescolano all’acrilico così come le superfici su cui sceglie di operare trascendono la comune tela, infatti l’artista predilige il lino e la juta sulla base della sensazione che desidera raccontare e di quanto consistente e ruvido debba essere il messaggio espresso con le materie che utilizza.

La tela Luci nel turbinìo, da lontano sembra ricondurre la memoria a un paesaggio crepuscolare nebbioso dove i fari delle auto, o le finestre accese, divengono guida e punto di riferimento; nel momento però in cui ci si avvicina all’opera emerge una fitta rete che rimanda all’impossibilità di vedere con chiarezza, come se tutto fosse confuso dalle distrazioni, dalle false certezze, da quella tendenza a galleggiare in superficie senza andare più a fondo. Il turbinìo di cui parla il titolo è dunque la quotidianità, il dover correre dietro agli impegni a cui far fronte che inducono l’individuo a essere distratto, a guardare senza vedere davvero le vere luci che possono nascondersi oltre la prima patina osservabile.

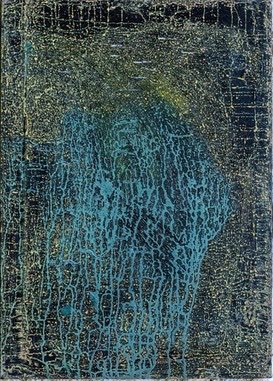

Nell’opera Natura divina invece la rete, di tonalità differenti, in questo caso svela, lascia emergere un’essenza immateriale che pur essendo di fatto in tutte le cose in realtà non viene notata fino al momento in cui qualcosa la porta alla luce; qui dunque l’effetto ottico è contrario alle altre opere, infatti è grazie a quella patina rugosa che fuoriesce l’essenza, definita da un nucleo cromatico evidenziato dall’azzurro, il colore del sogno e della spiritualità, con cui si manifesta quella presenza rassicurante e rasserenante. Helena Manzan suggerisce di porre maggior ascolto al divino che avvolge ogni cosa perché è solo grazie a quel contatto che è possibile comprendere il positivo esistente anche all’interno di circostanze apparentemente negative, quella capacità di intuire quanto in fondo tutto sia funzionale a un ordine superiore e a una progressione dello spessore personale di ciascuno.

Poi l’artista si sposta verso un punto di osservazione meno impalpabile e immortala attimi poetici attraverso il suo filtro interpretativo, come nel caso della tela Ultima rosa del giardino dove emerge una luminosità più intensa, proprio perché l’approccio alla realtà è rasserenato dalla capacità di lasciarsi cullare dalla piacevolezza della natura, della tranquillità che solo il contatto con la bellezza più pura e spontanea, in questo caso quella dei fiori, riesce a infondere; Helena Manzan in questo caso inserisce dei fiori essiccati, dando non solo consistenza all’opera bensì cercando di infondere all’osservatore la medesima sensazione provata da lei nel momento in cui si è persa nella contemplazione di quel frangente. Le tonalità sono morbide, tenui, giocate sui verdi, sui rosa, sui gialli e sui beige, per suggerire quanto sia delicato e impalpabile il mondo floreale, vicino eppure distante a causa di un vivere contemporaneo che convince l’individuo a concentrarsi su altre priorità.

Helena Manzan, laureata presso l’Accademia d’Arte dell’Università Federale di Uberlandia, Minas Gerais, Brasile, comincia fin dagli anni Novanta a esporre in America e in Europa; ha al suo attivo mostre in Brasile e in Italia, a New York, Londra, Lisbona, Belfast, Siviglia , Osaka, Helsinki e Novosibirsk.

The smoky atmospheres and fragmentation grids of reality in Helena Manzan’s Abstract Expressionism

The pictorial approach of each creative is expressed through the filter of interiority, of the way of observing everything that revolves around, but also of the ability to go beyond the superficial patina of contemporaneity and of the sensations that belong to the point of observation from which each artist starts out; in some cases, the research goes so deep that it needs smoke and darkness in order to be able to tend towards light at a later stage, a metaphor for self-knowledge and that which is external to oneself. The artist I am going to tell you about today tackles the world of darkness, of penumbra, intended as a silent space in which to lose oneself in order to then be able to find the meaning of an emotion by breaking out of that network of certainties that all too often become obstacles to a freer interpretation of what is seen and experienced.

The pictorial movement born in the United States around the mid-1950s, known as Abstract Expressionism, immediately showed one of its fundamental guidelines and that is the freedom of expression that could not, and should not, be conditioned by rules and schemes that were not those of the author of the artwork; what should not be lacking, instead, was the emotion told, faced, manifested on the basis of the creative artist’s character and interpreted according to his own personal point of view. It goes without saying that the abstract basis was thus indulged in pure instinct, at times more lively or overwhelming, at others more reflective and meditative, while having the common denominator of stimulating a reaction in the observer, whether it was involvement, an emotional shock or a cue for meditation. Thus, the pictorial impetus of Jackson Pollock and Lee Krasner, where Dripping and the gesture to carry it out became not only part of the painting itself but also a way of implying how each individual sensation had its own personality expressed through different and multiple colours, was answered by the calmer temperament but always oriented towards the intensity of the chromatic range of Mark Rothko and Barnett Newman, the latter tending towards the monochrome of Minimalism; the tonal solarity of Hans Hofmann and Morris Louis, where there were no limits to the combination of colours, as if their presence was the only possible dialogue with the viewer, contrasted with the sign painting characterised by intense and incisive two-tone colours of Franz Kline and Robert Motherwell, for whom the feeling had to be deprived of any distracting embellishment.

Among them, however, there were also more intimist artists, more oriented towards trying to bring out the limits and conditioning of the human being in the society of the time, in which painting took on earthy, smoky tones, precisely to indicate the often flattening everyday life; the paintings of these artists were accompanied by scratches, thin lines furrowing the surfaces precisely to emphasise how necessary it was to dig and go beyond in order to be able to understand the meaning of it all. In this last subgroup of Abstract Expressionist exponents were William Congdon, where the cracks in the colour allowed subtle and stylised figuration to emerge, and Mark Tobey in whom the marks, the writing, the lines seemed to cover reality, in each case marked by dark backgrounds, dark as the night of knowledge is when it is unable to plunge beyond those apparent barriers. The pictorial style of artist Helena Manzan, of Brazilian and Venetian origin, who has lived in Italy for many years now, seems to constitute a synthesis between Congdon’s scratches, where the material element contributes to giving prominence to certain parts of the composition, and Tobey’s lines, while from both she inherits the backgrounds that are at times darker at others clearer, but always as if the process of learning, of discovering the meaning of her canvases, did not want to reveal too much, remained constantly whispered, hinted at to induce the observer to reflection, to a path of profound understanding, just as introspective is her in the creative act. What emerges clearly from Helena Manzan’s artworks is the awareness of how everything is covered by a dense net of appearances, which she recounts in the form of a reticle which in fact represents the contemporary individual’s inability to dwell on what lies beyond, to try to observe more attentively what lies behind the false certainties and surfaces that many convince themselves are the truth.

Helena Manzan seems to invite the observer not to be afraid to face the dark because in fact all, everything, every path, is necessary to bring closer to the light, understood as self-awareness and everything that revolves around the human being, constituting his daily life; it is only after the courageous choice of entering into that grid of illusions that evolution can take place, a greater awareness, thus finding one’s own light, the light that will be able to dissolve shadows, uncertainties and fears. Manzan’s artworks therefore constitute a veritable quest to emphasise which she makes use of unpublished materials, giving life to a mixed technique that is barely perceptible but which expands the final meaning of the painting, becoming its completion, because it is only through the visionary capacity to find unthought-of solutions that one can strive towards a knowledge that is not the common one, which is often deceptive, but rather the personal, individual and perhaps for this reason more real. Ashes, hay, dried flowers, enamels, are mixed with acrylic as well as the surfaces on which she chooses to work transcend the common canvas, in fact the artist prefers linen and jute on the basis of the sensation she wishes to tell and how consistent and rough the message expressed with the materials she uses must be. The canvas Lights in the swirl, from a distance seems to bring back memories of a foggy twilight landscape where car headlights, or lit windows, become a guide and a point of reference; however, as one approaches the work, a dense net emerges that refers to the impossibility of seeing clearly, as if everything were confused by distractions, by false certainties, by that tendency to float on the surface without going deeper.

The swirl of which the title speaks is therefore everyday life, the need to run after commitments to be faced, which induces the individual to be distracted, to look without really seeing the true lights that may be hiding beyond the first observable patina. In the canvas Divine Nature, on the other hand, the net, in different shades, in this case reveals, lets emerge an immaterial essence that, although it is in fact in all things, is not really noticed until the moment when something brings it to light; here, therefore, the optical effect is the opposite of the other artworks, in fact it is thanks to that wrinkled patina that the essence emerges, defined by a chromatic nucleus highlighted by blue, the colour of dreams and spirituality, with which that reassuring and calming presence is manifested. Helena Manzan suggests that we should listen more to the divine that envelops everything because it is only through that contact that it is possible to understand the positive that exists even within apparently negative circumstances, that ability to perceive how everything is basically functional to a higher order and to a progression of each person’s personal depth. Then the artist shifts towards a less impalpable point of observation and immortalises poetic moments through her interpretative filter, as in the case of the canvas Last Rose in the Garden where a more intense luminosity emerges, precisely because the approach to reality is soothed by the ability to let oneself be lulled by the pleasantness of nature, of the tranquillity that only contact with the purest and most spontaneous beauty, in this case that of flowers, can instil; Helena Manzan in this case inserts dried flowers, giving not only consistency to the work but also trying to instil in the observer the same sensation she felt when she was lost in contemplation of that moment. The tones are soft, subdued, playing on greens, pinks, yellows and beiges, to suggest how delicate and impalpable the floral world is, close and yet distant due to contemporary living that convinces the individual to focus on other priorities. Helena Manzan, a graduate of the Art Academy of the Federal University of Uberlandia, Minas Gerais, Brazil, has been exhibiting in America and Europe since the 1990s; she has exhibitions in Brazil and Italy, New York, London, Lisbon, Belfast, Seville , Osaka, Helsinki and Novosibirsk to her credit.