Vivere nell’era contemporanea non è semplice, non lo è per l’essere umano e men che meno per soggetti sensibili come gli artisti che non possono evitare di sentirsi in qualche modo travolti dagli eventi e dalle circostanze e che, proprio in virtù della loro capacità espressiva riescono a liberare sulla tela le sensazioni interiori da cui si sentono afflitti e al tempo stesso comunicando al resto del mondo ciò che chiunque sente nel profondo senza però essere capace di esternarlo. Ecco dunque che il compito del creativo è non solo di manifestazione della propria interiorità e del personale punto di vista bensì si fa interprete e testimone di un periodo storico, dell’epoca in cui il suo cammino artistico si compie e voce narrante di chi resta in silenzio pur condividendo. Il protagonista di oggi sceglie un linguaggio immediato e istintivo per far sentire la propria voce interiore.

Intorno al primo decennio del Novecento cominciò a delinearsi l’esigenza di distaccarsi dall’immagine osservata per dare voce al solo intento espressivo e al sentire attraverso forme linee e colori, questo almeno nell’originaria intenzione di quello che è a tutt’oggi considerato il fondatore e principale esponente dell’Astrattismo, Vassily Kandisky; tuttavia ben presto, soprattutto in Olanda e in Russia, si formarono due movimenti, il Neoplasticismo e il Suprematismo, che affermarono invece l’importanza e la predominanza del gesto plastico sull’emozione la quale non doveva essere parte dell’opera. A seguito della consapevolezza della limitatezza di quell’originario rigore fu introdotta un’interpretazione differente e più ampia in altre parti d’Europa, in particolare in Italia dove l’uso dei soli colori primari e delle forme quadrate o rettangolari era ritenuto troppo limitante e freddo nei confronti dell’osservatore che automaticamente si distaccava da quello schema eccessivamente rigido; da quelle linee guida differenti nacque l’Astrattismo Geometrico che si diffuse ampiamente in particolar modo nel Nord Italia. Con il sopraggiungere delle due guerre mondiali però gli artisti che scelsero di avvicinarsi all’espressione attraverso la non forma, al distacco dalla realtà osservata, sentirono di non poter più trattenere quel mondo interiore che troppe ferite portava in sé proprio a seguito delle brutture e delle sofferenze vissute e osservate durante i conflitti. Fu così che, a partire dagli Stati Uniti dove molti fuggitivi dal Vecchio Continente si rifugiarono, vide la nascita l’Espressionismo Astratto, un movimento pittorico in cui la libertà espressiva doveva essere funzionale all’accordo con quel mondo emozionale che non doveva più essere escluso dall’opera d’arte bensì doveva esserne elemento fondante e irrinunciabile. L’innovazione stilistica non poteva non ripercuotersi anche in Italia dove fu data un’impronta diversa poiché laddove nella corrente fondata da Jackson Pollock, Franz Kline, Hans Hoffman, Willem de Koonig e Clyfford Still, il gesto, l’atto di stendere il colore ciascuno con la propria tecnica che passava dal Dripping al Color Field, dal Tachisme alla pittura segnica, entrava a far parte dell’opera stessa, nell’Arte Informale italiana fu la materia invece a essere posta in sinergia con quel sentire intenso e travolgente che gli artisti come Alberto Burri non riuscivano a trattenere avvertendo il bisogno di enfatizzarlo e concretizzarlo con l’utilizzo di plastiche, iuta, legni, bruciati e tagliati sulla base della sofferenza interiore o dell’emozione del momento.

In questo contesto di libertà espressiva e di necessità di accordare la non immagine all’interpretazione profonda e personale della realtà osservata, o forse sarebbe meglio dire ascoltata intorno a sé, si inserisce la produzione pittorica dell’artista ligure Roberto Buccilli, decisamente appartenente all’Espressionismo Astratto proprio per la sua tendenza a trasformare il gesto stesso in elemento essenziale della tela; si avvale infatti di spatole o pennelli, ricorre al Grattage oppure stende il colore in maniera densa, rendendolo definito solo nei dettagli che ritiene di mettere in evidenza, a seconda della sensazione che sente il bisogno di immortalare, o del concetto esistenziale che vuole sottoporre all’attenzione del fruitore perché sa che in fondo dipingere corrisponde a proporre a chi osserva uno spunto di riflessione, un contatto empatico, la possibilità di riconoscersi in quelle tonalità espressive, in quelle variazioni cromatiche che costituiscono l’essenza stessa della tela.

In alcuni casi più meditativo, quasi vicino al Color Field di Mark Rothko, in altri più impulsivo attraverso un Dripping in cui il bastoncino agisce in maniera rapida, incontrollata, quasi a essere il prolungamento dell’impeto creativo dell’artista il quale effettua un percorso introspettivo sul suo cammino, che per esteso è quello dell’uomo contemporaneo, sulle circostanze che si susseguono e sulle situazioni che hanno fatto parte della sua vita come di quella di chiunque.

Ecco perché è facile sentir vibrare le corde emotive davanti alle sue opere di grande impatto, di incisivo effetto cromatico in grado di scuotere le coscienze, di cogliere quel particolare dettaglio in grado di colpire il punto emozionale che ha bisogno di emergere.

Nella tela Il sentiero della vita Buccilli evidenzia una linea arancio che si staglia sullo spazio blu circostante e che, pur cercando di essere diritta e delineata deve suo malgrado accogliere quelle deviazioni, quei frastagliamenti che rappresentano gli ostacoli, i cambiamenti necessari a generare l’evoluzione a cui l’uomo spesso resiste ma che costituiscono l’essenza stessa della vita; quel frastagliamento, solo apparentemente elemento di disturbo, nella realtà dei fatti è invece una risorsa, un’implementazione della conoscenza di sé, della propria determinazione e della propria forza, e va a stimolare l’elasticità funzionale al sapersi adattare alle situazioni pur non perdendo di vista l’obiettivo finale, quello cioè di essere felici.

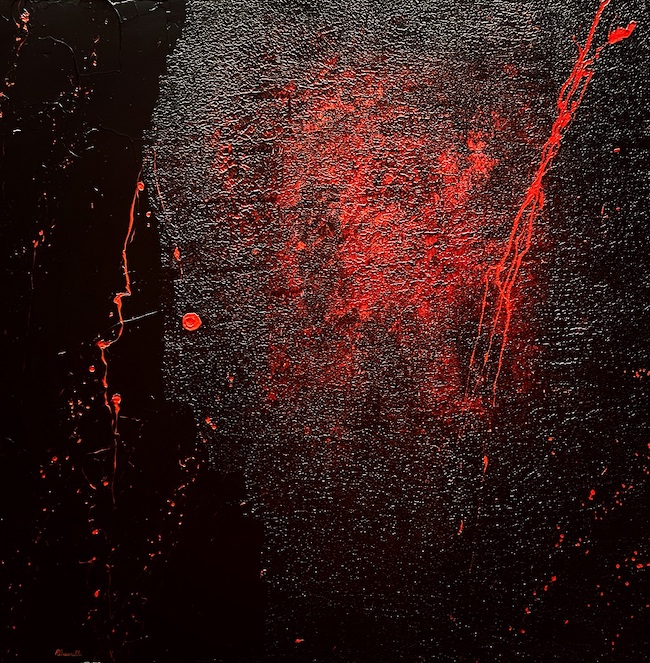

In Ferite l’approccio è meditativo seppur intenso e amplificato dal colore rosso alla base che emerge dal buio sovrastante, come se tutto ciò che provoca una sofferenza tendesse a restare nel luogo più nascosto, più profondo dell’animo per evitare che il mondo produca altre cicatrici, più dolorose e profonde; dunque il rosso può essere interpretato come il colore del sangue, quello delle ferite che appartengono all’interiorità quanto all’inevitabile corso dell’esistenza, mentre il nero costituisce la necessità di osservare quel dolore nella solitudine e nel silenzio. La scelta che si delinea è quella di subirlo e lasciarsi andare all’autocommiserazione oppure accoglierlo, considerarlo come parte del proprio personale percorso e risollevarsi, è questo forse il senso delle gocce rosse che sembrano elevarsi verso il buio della parte superiore della tela, quella resilienza che induce l’individuo a non piegarsi alle circostanze e al destino bensì a contrastarlo e resistere per andare verso un domani migliore.

E ancora in Behind the immagination, dove emerge un lieve accenno di Tachisme, Roberto Buccilli sottolinea quanto tutto ciò che appare possa avere un significato differente, nascosto a volte da strati di verità illusorie, rappresentate dal tocco netto della spatola, che solo attraverso la capacità di vedere oltre quei veli si può scoprire; oppure al contrario, spesso la realtà è persino più complessa dell’immaginazione, perché andando a fondo delle questioni e delle situazioni si possono portare alla luce evidenze che altrimenti resterebbero celate, verità che diversamente continuerebbero a essere considerate come parte di un immaginario comune che grazie a quell’osservazione più attenta, si rivela essere molto più reale di quanto si sarebbe previsto.

Si spinge sempre verso un approfondimento l’approccio pittorico di Buccilli, tende costantemente ad ascoltare il non detto, a scostare quei veli dentro cui le realtà si nascondono e ad andare verso profondità che sono oltre la superficie, l’apparenza, quella pellicola esterna su cui i più si soffermano, un po’ per abitudine, un po’ per pigrizia e un po’ perché non hanno la capacità di comprendere quale ricchezza vi sia oltre. Geometra di professione ma da sempre appassionato d’arte al punto di diventare collezionista di pittori liguri emergenti, Roberto Buccilli da qualche anno ha deciso di lasciarsi andare a quell’impulso creativo che in maniera latente gli apparteneva da sempre, mostrando un innato talento espressivo; è rappresentato in esclusiva dalla galleria MC Art di Marcella Curcio a Noli e negli stand da lei curati ad Arte Genova, Arte Parma, Paviart, Arte Pavia, presso la galleria storica San Donato a Genova e in contesti come il Real Collegio di Noli e Rivercase di Bergeggi, Noli e Spotorno.

ROBERTO BUCCILLI-CONTATTI

Email: robertobuccilli@libero.it

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/roberto.buccilli.3

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/buccillir/

Life paths and inner movements in the intense and intimist Abstract Expressionism of Roberto Buccilli

Living in the contemporary era is not easy, it is not easy for human beings and even less so for sensitive individuals such as artists who cannot avoid feeling in some way overwhelmed by events and circumstances and who, precisely because of their expressive capacity are able to release onto canvas the inner feelings from which they feel afflicted and at the same time communicate to the rest of the world what everyone feels deep down without being able to express it. So the creative artist’s task is not only to express his inner self and personal point of view, but also to be the interpreter and witness of a historical period, of the era in which his artistic journey takes place, and the narrator of those who remain silent while sharing. Today’s protagonist chooses an immediate and instinctive language to make his inner voice heard.

Around the first decade of the twentieth century, the need to detach oneself from the observed image began to emerge in order to give voice to the sole expressive intent and to feeling through forms, lines and colours, at least in the original intention of what is still considered the founder and main exponent of Abstractionism, Vassily Kandisky; however, two movements, Neo-Plasticism and Suprematism, were soon formed, especially in Holland and Russia, which affirmed the importance and predominance of plastic gesture over emotion, which was not to be part of the artwork. Following the awareness of the limitation of that original rigour, a different and broader interpretation was introduced in other parts of Europe, in particular in Italy where the use of only primary colours and square or rectangular shapes was considered too limiting and cold towards the observer who automatically broke away from that excessively rigid scheme; from those different guidelines Geometric Abstractionism was born and spread widely, especially in Northern Italy. With the coming of the two world wars, however, the artists who chose to approach expression through non-form, to detach themselves from the observed reality, felt they could no longer hold back that inner world that bore too many wounds as a result of the ugliness and suffering experienced and observed during the conflicts.

Thus it was that the United States, where many fugitives from the Old World took refuge, saw the birth of Abstract Expressionism, a pictorial movement in which expressive freedom had to be functional to the agreement with that emotional world that was no longer to be excluded from the artwork, but had to be a fundamental and indispensable element. The stylistic innovation could not fail to have repercussions in Italy too, where a different imprint was given since, while in the current founded by Jackson Pollock, Franz Kline, Hans Hoffman, Willem de Koonig and Clyfford Still, the gesture, the act of spreading the colour, each with his own technique that went from Dripping to Color Field, from Tachisme to sign painting, became part of the artwork, in Italian Informal Art, on the other hand, it was the material that was placed in synergy with that intense and overwhelming feeling that artists such as Alberto Burri were unable to hold back, feeling the need to emphasise and concretise it with the use of plastic, jute and wood, burnt and cut on the basis of inner suffering or the emotion of the moment. In this context of expressive freedom and the need to tune the non-image to the profound and personal interpretation of the reality observed, or perhaps it would be better to say listened to, around him, the pictorial production of the Ligurian artist Roberto Buccilli fits in. He definitely belongs to Abstract Expressionism precisely because of his tendency to transform the gesture itself into an essential element of the canvas; in fact, he uses spatulas or brushes, he resorts to Grattage or he spreads the colour in a dense way, making it defined only in the details that he wants to highlight, depending on the sensation that he feels the need to immortalise, or on the existential concept that he wants to bring to the viewer’s attention because he knows that, after all, painting corresponds to offering the observer a cue for reflection, an empathic contact, the possibility of recognising himself in those expressive tonalities, in those chromatic variations that constitute the very essence of the canvas.

In some cases more meditative, almost close to Mark Rothko’s Color Field, in others more impulsive through Dripping in which the stick acts in a rapid, uncontrolled manner, almost as if it were an extension of the creative impetus of the artist who carries out an introspective journey on his path, which in full is that of contemporary man, on the circumstances that follow one another and on the situations that have been part of his life as well as that of anyone else. This is why it is easy to feel the emotional chords vibrating in front of his works of great impact, of incisive chromatic effect capable of shaking consciences, of grasping that particular detail capable of striking the emotional point that needs to emerge. In the painting Il sentiero della vita (The Path of Life), Buccilli highlights an orange line that stands out against the surrounding blue space and which, while trying to be straight and delineated, must in spite of itself accommodate those deviations, those jagged edges that represent the obstacles, the changes necessary to generate the evolution that man often resists but which constitute the very essence of life; that jaggedness, only apparently a disturbing element, is actually a resource, an implementation of self-knowledge, of one’s own determination and strength, and stimulates the functional elasticity of knowing how to adapt to situations without losing sight of the final objective, that is to be happy. In Ferite (Wounds) the approach is meditative yet intense and amplified by the red colour at the base which emerges from the darkness above, as if everything that causes suffering tends to remain in the most hidden, deepest place of the soul to prevent the world from producing other, more painful and deeper scars; thus red can be interpreted as the colour of blood, that of the wounds that belong to the interiority as much as to the inevitable course of existence, while black represents the need to observe that pain in solitude and silence.

The choice that emerges is either to suffer it and allow oneself to feel sorry, or to welcome it, to consider it as part of one’s own personal journey and to rise up again. This is perhaps the meaning of the red drops that seem to rise up towards the darkness of the upper part of the canvas, that resilience that induces the individual not to bend to circumstances and destiny but to resist it and move towards a better tomorrow. And again in Behind the Imagination, where a slight hint of Tachisme emerges, Roberto Buccilli underlines how everything that appears can have a different meaning, sometimes hidden by layers of illusory truths, represented by the sharp touch of the palette knife, which only through the ability to see beyond those veils can be discovered; or, on the contrary, reality is often even more complex than the imagination, because by going to the bottom of issues and situations, one can bring to light evidence that would otherwise remain hidden, truths that would otherwise continue to be considered as part of a common imagination that, thanks to that closer observation, turns out to be much more real than one would have expected. Buccilli’s pictorial approach always goes towards a deepening, he constantly tends to listen to the unspoken, to peel back those veils within which realities are hidden and to go towards depths that are beyond the surface, the appearance, that external film on which most people dwell, partly out of habit, partly out of laziness and partly because they do not have the capacity to understand what richness there is beyond. A surveyor by profession but always a passionate art lover to the point of becoming a collector of emerging Ligurian painters, Roberto Buccilli has decided to let himself go to that creative impulse that has always been latent in him, showing an innate expressive talent; he is represented exclusively by Marcella Curcio’s MC Art gallery in Noli and in the stands she curates at Arte Genova, Arte Parma, Paviart, Arte Pavia, at the historic San Donato gallery in Genoa and in contexts such as the Reale Collegio di Noli and Rivercase in Bergeggi, Noli and Spotorno.