La quotidianità, quegli scorci da sempre parte della vita dell’individuo ma troppo spesso trascurati, a malapena notati proprio in virtù di quella costante presenza, costituisce a volte un punto di partenza per una fuga da parte della coscienza per elevarsi e sognare luoghi lontani, più o meno immaginari ma comunque necessari all’interiorità a effettuare quel distacco da una contingenza spesso intrappolante; eppure esistono, e sono esistiti, molti artisti per i quali invece il soffermarsi su quelle immagini conosciute e familiari ha costituito un’importante parte della loro produzione artistica in cui viene messo in primo piano tutto ciò che la distrazione della routine indurrebbe a sottovalutare e rendendo così protagonisti, a volte assoluti, angoli di spazio che altrimenti non sarebbero stati presi in considerazione. L’artista di cui vi racconterò oggi esplora quelle realtà quotidiane attraverso uno sguardo attento ma al tempo stesso interiore, come se volesse indagare il significato che si cela nelle ambientazioni esplorate.

Nella pittura precedente a quella del Ventesimo secolo, i contesti che circondavano la figura umana erano pressoché complementi, sfondi, attraverso cui l’artista esaltava la ricchezza e l’importanza sociale dei personaggi ritratti, oppure, soprattutto con il Realismo della seconda metà dell’Ottocento, sottolineavano le origini umili degli interni delle botteghe artigiane o del popolo che viveva in condizioni disagiate rispetto ai pochi che detenevano il potere economico. Con l’affermarsi dell’Espressionismo, un movimento rivoluzionario poiché cambiò completamente il punto di vista sulla realtà nonché l’approccio pittorico e stilistico della struttura stessa dell’opera d’arte, i luoghi in cui i protagonisti di una tela vivevano divenivano talmente importanti da essere il riflesso delle sensazioni percepite e respirate dallo stesso artista nell’atto creativo. Ma soprattutto in alcuni casi divennero talmente prioritari da essere essi stessi protagonisti di un’opera a cui era sottratta la figura umana, lasciando nell’osservatore la sensazione della rilevanza di quegli spazi, dell’importanza costituita in un frangente o nel corso di un’intera vita, di quei perimetri limitati eppure familiari e necessari all’essere umano. Tra i maestri dell’Espressionismo che più si dedicarono a riprodurre ambienti intesi come complemento dell’esistenza, come luoghi in cui di fatto la vita, con la sua semplicità, scorre, fu Henri Matisse, nella sua fase Fauves, il quale armonizzava le tonalità intense degli interni e i contorni definiti delle carte da parati, delle sedie e dei letti, al significato emotivo che per i suoi protagonisti rivestivano; ma anche Vincent Van Gogh narrò in alcune sue celeberrime opere, come La stanza di Arles, tutta la forza di un luogo familiare, magico nella sua semplicità, forza che fuoriusciva del rapporto tra tratto espressivo e gamma cromatica. E ancora il Realismo Americano di Edward Hopper approfondì l’interrelazione tra l’essere umano, la sua profonda solitudine, e gli interni in cui la sua vita inevitabilmente scorre, trasformando i luoghi casalinghi in vere e proprie prigioni dorate all’interno di cui rifugiarsi e che in realtà non facevano che accentuare il senso di isolamento dalla socialità.

L’artista lombardo Paolo Vignati affronta il tema degli interni con un tratto fortemente espressionista, sia per quanto riguarda la scelta cromatica e sia per le linee di contorno attraverso cui evidenzia i profili di quegli oggetti o arredi che diventano protagonisti assoluti di un mondo in cui l’uomo è spesso assente oppure, al contrario, appare rinchiuso all’interno della sua quotidianità sempre più isolato dal mondo esterno, solo con se stesso; tuttavia la sua produzione artistica non riesce a soffermarsi su un solo punto di vista, o restare dentro una sola definizione stilistica, esplorando pertanto anche altre modalità espressive, pur rimanendo all’interno dell’Espressionismo che gli consente di mettere l’emotività in primo piano, a discapito della proporzione, dell’armonia delle forme, dell’equilibrio estetico che potrebbe distrarre dall’intensità del sentire.

Dunque i suoi passaggi formali divengono essenziali per lui per misurarsi con sfide sempre nuove, con esplorazioni che possono condurre verso evoluzioni, verso sperimentazioni in grado di aprire ancor più la sua predisposizione all’ascolto, alla contemplazione di tutto ciò che riguarda l’esterno in relazione con l’interiorità che inevitabilmente appartiene alla vita. Quando infatti ha bisogno di interrogarsi sulle sensazioni o sugli enigmi dell’esistenza, Paolo Vignati tende verso l’Astrattismo, come se l’ambito più misterioso, quello in cui farsi domande e cercare risposte, non potesse legarsi a un’immagine reale bensì dovesse necessariamente entrare nel campo dell’indefinito, della fantasia funzionale a esplorare il mondo con lo sguardo interiore e non quello oggettivo.

L’opera Misunderstood forms indaga infatti su tutto ciò che abitualmente non viene compreso, e molto spesso persino ignorato a causa della sua indecifrabilità e che Vignati rappresenta come una non forma, o meglio, una somma di forme che diventano quasi una massa unica, un nucleo dentro il quale andare a scoprire ciascuno la propria risposta, la singola interpretazione. Perché in fondo tutto ciò che l’essere umano può fare è basarsi su se stesso, sulla propria sensibilità, sull’esperienza che ha avuto sino a quel momento, per risolvere i quesiti universali tanto quanto quelli più pratici, perché di fatto una verità assoluta non esiste.

In Storm invece l’artista affronta il buio, la cupezza di una tempesta, intesa sia nel senso letterale dell’evento atmosferico in cui il cielo si oscura e avvolge di cupa umidità tutto ciò che è sotto di sé, sia in senso interiore, quando cioè l’individuo è costretto a oltrepassare un ostacolo inizialmente insormontabile ma che deve necessariamente combattere generando quello scontro di forze che però gli permetterà di giungere a un’evoluzione della propria essenza. Gli sprazzi di arancione costituiscono l’energia umana solo momentaneamente sovrastata dalla forza delle opposizioni.

Ma è nelle opere più fortemente figurative che si svela il talento espressivo di Paolo Vignati, come in Domestic Imagination, opera in cui lascia emergere la desolazione e l’isolamento dell’uomo contemporaneo, quel suo trovarsi in dialogo con un apparato tecnologico, il televisore, che diviene unico compagno per alleviare la solitudine, illusione di essere parte di un mondo, quello esterno, che non può essere vissuto e dunque va guardato, ignaro che spesso è proprio attraverso quella stessa tecnologia che avviene la manipolazione, la dipendenza da programmi univoci che tendono ad appiattire il pensiero critico. L’invito dell’artista è dunque quello di osservare la realtà con maggiore lucidità e consapevolezza e non permettere, solo perché si è incapaci o impossibilitati a relazionarsi con la vita reale, di farsi condizionare la mente al punto di dimenticare di essere umani.

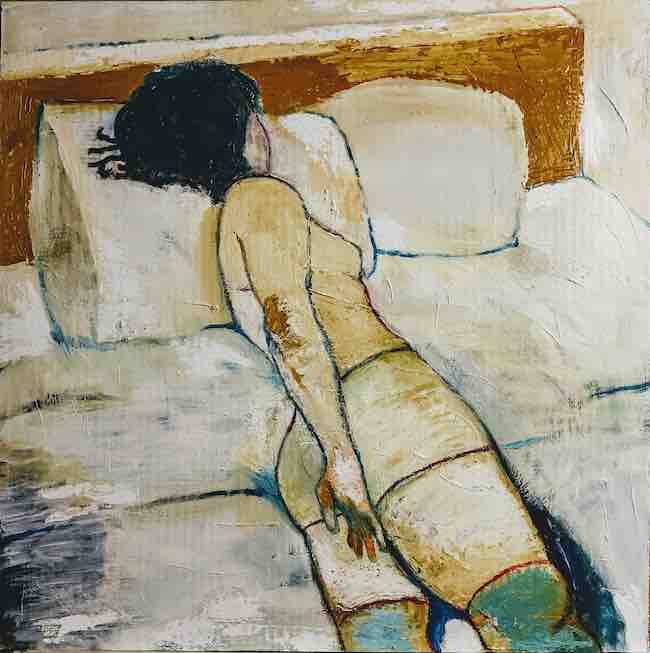

In Female Attraction Vignati si avvicina a un’ulteriore modificazione dello stile, quella che lo fa tendere più verso l’Espressionismo di Egon Schiele poiché ciò che conta in quest’opera è l’atmosfera, la sensualità espressa dal corpo femminile e la consapevolezza che spesso è proprio in quella nudità, in quella spontaneità che si nasconde ciò che è necessario all’interiorità umana; come Schiele infatti l’artista suggerisce che quando tutto sembra essere perduto, quando la realtà circostante è troppo incomprensibile, o triste, o destabilizzante, è sufficiente ritrovare il contatto con la primordialità di un abbraccio, con la piacevolezza dell’intimità per indurre l’uomo a sentirsi comunque sollevato, appagato, meno perso. Il contorno è netto e definito, mentre la gamma cromatica è leggera, delicata, giocata sui toni del bianco, del beige e del marroncino, perché l’essenzialità e l’immediatezza non hanno bisogno di troppi abbellimenti.

Paolo Vignati, nato e cresciuto nella provincia lodigiana, comprende fin da giovane la sua attitudine artistica e si iscrive al Liceo Artistico; successivamente compie le prime esperienze professionali attraverso periodi di tirocinio nella grafica digitale per poi distaccarsi professionalmente dalla sua inclinazione naturale che però torna a farsi sentire in modo forte dopo qualche anno e da quel momento decide di dedicarsi esclusivamente all’arte, ricominciando a esporre le sue opere in mostre collettive in Italia e all’estero. Attualmente ha collaborazioni ben consolidate con la Agora Arts Gallery di New York, con la Mads Galleria di Milano e con Itsliquid Group di Venezia.

PAOLO VIGNATI-CONTATTI

Email: spaziolabor@outlook.it

Sito web: https://www.spaziolabor.it/

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/paolo.francesco.vignati

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/paolo_francesco_vignati/

Paolo Vignati’s Expressionism, amidst fragments of everyday life and indefinable forms belonging to the imagination

Everyday life, those glimpses that have always been part of the individual’s life but are too often neglected, barely noticed precisely because of that constant presence, is sometimes a starting point for an escape on the part of the conscience to elevate itself and dream of faraway places, more or less imaginary but nevertheless necessary for the interiority to effect that detachment from an often trapping contingency; yet there exist, and have existed, many artists for whom, instead, dwelling on those known and familiar images has constituted an important part of their artistic production in which everything that the distraction of routine would induce to underestimate is brought to the foreground, thus making corners of space that otherwise would not have been taken into consideration the protagonists, sometimes absolute. The artist I am going to tell you about today explores those everyday realities through an attentive but at the same time interior gaze, as if he wanted to investigate the meaning hidden in the settings explored.

In painting prior to the 20th century, the settings surrounding the human figure were almost complements, backdrops, through which the artist exalted the wealth and social importance of the characters portrayed, or, especially with the Realism of the second half of the 19th century, emphasised the humble origins of the interiors of artisans’ workshops or of the people living in poor conditions compared to the few who held economic power. With the rise of Expressionism, a revolutionary movement as it completely changed the point of view on reality as well as the pictorial and stylistic approach to the very structure of the artwork, the places where the protagonists of a canvas lived became so important that they transformed in a reflection of the sensations perceived and breathed by the artist himself in the creative act. But above all, in some cases they were such a priority that they were themselves the protagonists of a work from which the human figure was removed, leaving the observer with the sensation of the relevance of those spaces, of the importance constituted at a juncture or in the course of an entire life, of those limited perimeters that are nevertheless familiar and necessary to the human being.

Among the masters of Expressionism who most devoted themselves to reproducing environments intended as a complement to existence, as places in which life, with its simplicity, actually flows, was Henri Matisse, in his Fauves phase, who harmonised the intense tones of the interiors and the defined contours of the wallpapers, chairs and beds with the emotional significance they held for his protagonists; but also Vincent Van Gogh narrated in some of his celebrated paintings, such as The Room at Arles, all the strength of a familiar place, magical in its simplicity, a strength that came out of the relationship between expressive stroke and chromatic range. And again Edward Hopper’s American Realism deepened the interrelation between the human being, his profound solitude, and the interiors in which his life inevitably flows, transforming domestic places into real gilded prisons within which to take refuge and which in reality only accentuated the sense of isolation from sociality. The Lombard artist Paolo Vignati tackles the theme of interiors with a strongly expressionist trait, both in his choice of colour and in the contour lines through which he highlights the outlines of those objects or furnishings that become the absolute protagonists of a world in which man is often absent or, on the contrary, appears enclosed within his everyday life, increasingly isolated from the outside world, alone with himself; however, his artistic production does not manage to dwell on a single point of view, or remain within a single stylistic definition, and therefore also explores other modes of expression, while remaining within Expressionism, which allows him to put emotionality in the foreground, to the detriment of proportion, harmony of form, and aesthetic balance that might distract from the intensity of feeling. Therefore, his formal passages become essential for him to measure himself with ever new challenges, with explorations that can lead towards evolutions, towards experimentations capable of opening up even more his predisposition to listening, to the contemplation of everything that concerns the exterior in relation to the interiority that inevitably belongs to life. In fact, when he needs to question himself on the sensations or enigmas of existence, Paolo Vignati tends towards Abstractionism, as if the most mysterious field, the one in which to ask questions and seek answers, could not be linked to a real image but must necessarily enter the realm of the indefinite, of the fantasy functional to exploring the world with the inner and not the objective gaze. In fact, the artwork Misunderstood Forms investigates everything that is usually not understood, and very often even ignored because of its indecipherability, and which Vignati represents as a non-form, or rather, a sum of forms that become almost a single mass, a nucleus within which each one goes to discover its own answer, its own interpretation.

Because after all, all a human being can do is rely on himself, on his own sensitivity, on the experience he has had up to that moment, to resolve universal questions as much as the most practical ones, because in fact an absolute truth does not exist. In Storm, on the other hand, the artist tackles the darkness, the gloom of a storm, understood both in the literal sense of the atmospheric event in which the sky darkens and envelops everything underneath in gloomy humidity, and in the inner sense, when the individual is forced to overcome an obstacle that is initially insurmountable but which he must necessarily fight, generating that clash of forces that will, however, allow him to reach an evolution of his own essence. The flashes of orange constitute human energy only momentarily overpowered by the force of opposition. But it is in the more strongly figurative paintings that Paolo Vignati’s expressive talent is revealed, as in Domestic Imagination, a work in which he allows to emerge the desolation and isolation of contemporary man, his finding himself in dialogue with a technological apparatus, the television set, which becomes his only companion to alleviate his loneliness, an illusion of being part of a world, the outside world, that cannot be experienced and must therefore be watched, unaware that it is often through that very same technology that manipulation takes place, dependence on univocal programmes that tend to flatten critical thought. The artist’s invitation is therefore to observe reality with greater lucidity and awareness and not to allow, just because one is incapable or unable to relate to real life, one’s mind to be conditioned to the point of forgetting to be human.

In Female Attraction Vignati approaches a further modification of style, one that makes him lean more towards Egon Schiele’s Expressionism, since what counts in this canvas is the atmosphere, the sensuality expressed by the female body and the awareness that it is often in that very nudity, in that spontaneity, that what is necessary for human interiority is hidden; in fact, like Schiele, the artist suggests that when all seems to be lost, when the surrounding reality is too incomprehensible, or sad, or destabilising, it is enough to rediscover contact with the primordiality of an embrace, with the pleasantness of intimacy, to induce man to feel relieved, fulfilled, less lost. The outline is sharp and defined, while the colour range is light, delicate, played on shades of white, beige and brownish, because essentiality and immediacy do not need too many embellishments. Paolo Vignati, born and raised in the province of Lodi, realised his artistic aptitude at a young age and enrolled in the Liceo Artistico. He then gained his first professional experiences through periods of apprenticeship in digital graphics, before detaching himself professionally from his natural inclination, which, however, made itself felt strongly again after a few years. He currently has well-established collaborations with the Agora Arts Gallery in New York, the Mads Galleria in Milan and the Itsliquid Group in Venice.