La rappresentazione artistica nasce spesso dalla capacità del singolo autore di guardarsi intorno e cogliere attraverso la propria sensibilità tutto ciò che stimola le sue corde emozionali, andando a insinuarsi nella necessità di interpretare, o semplicemente manifestare, le sensazioni ricevute dall’oggettività circostante.

In alcuni creativi l’importanza di alcuni piccoli dettagli, dei minimi particolari della vita, diviene il focus su cui basano la loro intera produzione artistica, proprio perché il bisogno di indagare sui sottili misteri della contemporaneità, in quei tenui rivelatori di istanti, costituisce la base di partenza essenziale della loro ricerca in virtù della quale riescono a trasmettere nelle loro opere tutto quel senso di fascinazione che l’ambiente circostante esercita.

La protagonista di oggi effettua esattamente quel percorso di interiorizzazione di tutto ciò che il suo sguardo coglie casualmente e che poi si trasforma in opera d’arte in grado di sedurre e avvincere completamente l’osservatore.

La centralità che le sensazioni e le emozioni dell’artista e dei personaggi, così come dei panorami ritratti, avevano conquistato nella pittura dei primi decenni del Novecento, aprirono la strada a ricerche ed evoluzioni espressive che trasformarono l’esecuzione di un’opera in una vera e propria rivelazione di tutto quel sentire interiore che i singoli autori non riuscivano a manifestare nella quotidianità; dunque la soggettività dell’autore permeava la tela tanto quanto la sua forza empatica nell’interpretare ciò che il soggetto rappresentato provava nel momento in cui diveniva consapevole, o inconsapevole, protagonista di un dipinto che gli avrebbe regalato l’eternità. L’Espressionismo, il movimento che più di tutti si focalizzò proprio sull’essere umano, quasi a diventare in alcuni casi un’estensione dell’Esistenzialismo filosofico, mostrò tutte le debolezze dell’individuo in un periodo storico in cui le certezze decadevano, l’ipocrisia dell’aristocrazia diveniva evidente soprattutto davanti agli avvenimenti tragici che si susseguivano in Europa, e dove l’apparenza e l’attenzione all’estetica dei periodi precedenti non era più centrale nell’arte; Egon Schiele fu il caposcuola di uno sguardo sulla fragilità dell’essere umano, sui timori che si traducevano in ossessione per una sessualità costantemente manifesta, quasi ossessiva, che nascondeva l’esigenza di trovare una via d’uscita al senso di incertezza e di impotenza nei confronti delle circostanze esterne. Tanto quanto Edvard Munch concentrò la sua ricerca pittorica sull’ansia, l’angoscia di personaggi che in fondo erano riflesso di tutte le difficoltà e le sofferenze che l’autore aveva patito fin dall’infanzia, affidando così ai suoi protagonisti il proprio grido di dolore. Con il proseguire del Ventesimo secolo, le tematiche espressioniste vennero ampliate trasformandosi in analisi via via più profonda, psicologica pur senza mai perdere l’impatto emotivo, in particolar modo in quella Scuola di Londra di cui hanno fatto parte immensi rappresentanti come Lucian Freud, che con i suoi corpulenti corpi nudi ritratti in pose intime e quasi distaccate da tutto ciò che accadeva intorno riusciva a trasmettere il disagio del vivere in un’epoca disumanizzante, Francis Bacon, con le sue immagini di volti distorti e inquietanti frutto della percezione di una realtà causata dalla sofferenza interiore che lo accompagnava da sempre, e infine Paula Rego e Michael Andrews, in cui l’Espressionismo era meno cupo, più delicato e a volte sognante. L’artista di origine cinese Xinyi Cheng, non solo ha trovato a Parigi la sua seconda patria, ma è proprio nella capitale francese che ha avuto modo di sviluppare e lasciar evolvere la sua ricerca pittorica, grazie anche alla possibilità di spostarsi agevolmente in Europa per visitare i maggiori musei da cui ha potuto attingere ispirazione e affinare uno stile che mostrava fin dagli esordi un’impostazione rivolta completamente all’essere umano, al suo sentire, a tutto ciò che nella realtà contingente si nasconde ma che appare invece evidente a un’indagatrice sensibilità.

Xinyi Cheng porta infatti con sé la sua macchina fotografica in occasione di qualsiasi spostamento, anche nell’ambito della stessa Parigi, cogliendo piccoli frangenti delle persone che incontra nella sua strada, atteggiamenti inconsapevoli che stimolano la sua curiosità fino a scegliere di immortalarli e poi di interpretarli con la sua intensità espressiva.

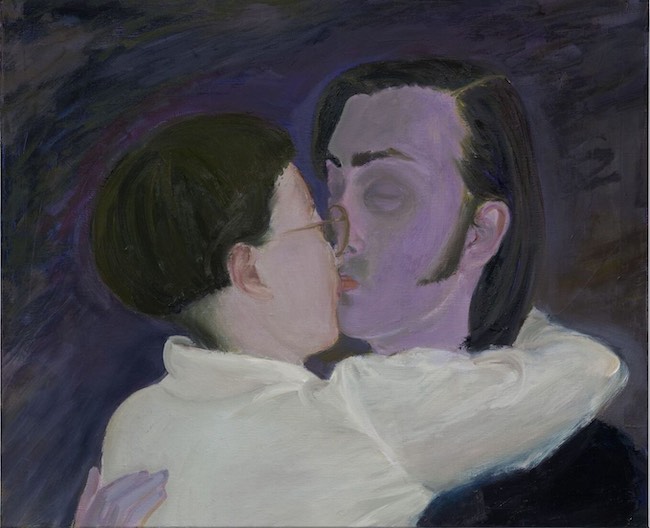

Le opere che ne derivano mostrano pertanto costantemente un’atmosfera irreale, come se il processo di interiorizzazione e di rivelazione che poi si è concretizzato sulla tela avesse decontestualizzato il soggetto dall’ambiente in cui si trovava nel momento dell’incontro con Xinyi Cheng, come se ciò che conta davvero fosse solo la sospensione che il sentire interiore suscita sia nella figura emanante la sensazione, dunque il protagonista del dipinto, sia nell’autrice che ne riceve le vibrazioni di cui avvolge il suo gesto pittorico.

La luce è un elemento insolito quanto variabile nelle sue opere e si associa al momento narrato, dunque in alcuni casi va semplicemente a enfatizzare un dettaglio mentre in altri si diffonde all’intera tela fino a sembrare quasi di voler raggiungere l’ambiente circostante divenendo ulteriore elemento di comunicazione con l’osservatore. La sensazione di irrealtà che avvolge i suoi personaggi sembra essere in contrasto con l’ordinarietà dei loro gesti, della loro normalità, quasi come se per Xinyi Cheng fosse proprio lì che si nasconde tutto ciò che ai suoi occhi diviene straordinario, quelle pose e quelle espressioni apparentemente insignificanti ma che possono costituire uno straordinario mezzo per scoprire l’intensità dei personaggi e l’essenza che l’artista è in grado di mettere in evidenza.

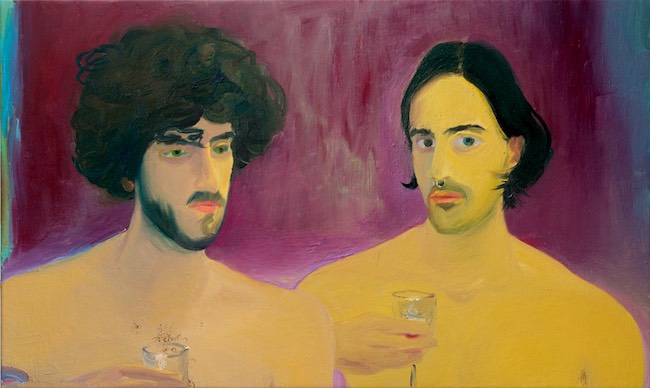

Nel periodo in cui ha studiato nei Paesi Bassi ha prodotto una serie di tele dedicate ai suoi amici omosessuali, perché uno dei cardini della ricerca artistica della Cheng è proprio il rapporto degli uomini con la mascolinità, con il modo di ciascuno di accogliere le proprie pulsioni e il proprio modo di essere, scavando però a fondo del loro sentire, indipendentemente dal genere perché ciò che conta è rivelarne l’essenza, il frangente di un istante in cui si abbandonano allo sguardo dell’artista.

In queste opere non si è avvalsa di scatti rubati bensì ha chiesto ai suoi modelli di posare, a volte nella loro nudità altre invece in situazioni surreali in cui dovevano lasciarsi andare alla fantasia e all’immaginazione, ed è stato proprio quello il frangente che è diventato protagonista di una tela; l’opera Stijn in the red bonnet è simbolica di questa parte della produzione di Xinyi Cheng, e racconta l’insicurezza, il timore del protagonista che forse si sta pentendo di aver acconsentito a scegliere proprio quella strana cuffia, o forse invece sta semplicemente ricordando un episodio durante il quale non si è sentito a suo agio riconducendolo al momento presente. Tutto sembra essere misterioso nelle atmosfere della Cheng, proprio perché lei non vuole dare una risposta univoca, piuttosto tende a fornire un ventaglio di possibilità interpretative di cui sarà primo attore ogni singolo osservatore che le declinerà sulla base della propria unica sensibilità.

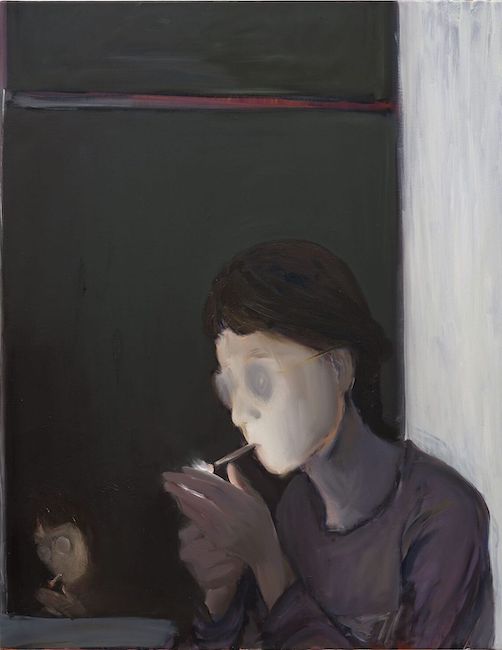

Le sigarette sono spesso co-protagoniste delle sue tele, quasi il gesto di fumare enfatizzasse la suggestione che l’artista affida ai personaggi, quasi come se davanti a quel semplice atto tutto divenisse più interessante, affascinante; nel dipinto For a light II i due giovani sembrano essere in procinto di raccontarsi gli aggiornamenti sulla loro vita, oppure al contrario sono semplicemente due sconosciuti che si sono trovati per caso al di fuori di un locale per lasciarsi andare a una pausa e probabilmente non hanno niente in comune se non la passione per la sigaretta. È questo ciò che colpisce delle opere della Cheng, l’impossibilità di dare una collocazione e un senso ben definiti alle scene, ai personaggi descritti, poiché lo spazio e il tempo sembrano essere sospesi, gli uomini e le donne enigmatici, presi all’interno di un proprio mondo che raccontano senza svelare, suscitando quell’impulso a effettuare una ricerca introspettiva che troppo spesso nel vivere contemporaneo viene tralasciata per far spazio al materialismo e all’urgenza del raggiungere gli obiettivi.

Xinyi Cheng invece si sofferma, prende fiato e medita, mettendo in luce tutto ciò che appartiene all’essere umano, tutto ciò che riguarda quella quotidianità che in fondo rappresenta la vita. Xinyi Cheng ha al suo attivo mostre museali personali presso l’Hamburger Bahnhof a Berlino, e Lafayette Anticipations a Parigi, ha preso parte a mostre collettive al Palais de Tokyo a Parigi, alla Renaissance Society a Chicago, alla Tredicesima Biennale di Shanghai e alla Borsa di Commercio a Parigi.

XINYI CHENG-CONTATTI

Email: contact@antenna-space.com

Sito web: http://antenna-space.com/en/artists/chengxinyi/

The observation of small fragments of existence in the Expressionism by Xinyi Cheng

Artistic representation often stems from the individual creator’s ability to look around and grasp, through his sensitivity, everything that stimulates his emotional chords, insinuating the need to interpret, or simply manifest, the sensations received from the surrounding objectivity. In some creatives, the importance of a few small details, of the tiniest details of life, becomes the focus on which they base their entire artistic production, precisely because the need to investigate the subtle mysteries of contemporaneity, in those tenuous revelations of instants, constitutes the essential starting point of their research by virtue of which they succeed in conveying in their artworks all that sense of fascination that the surrounding environment exerts. Today’s protagonist carries out exactly that process of internalising everything that her gaze catches by chance and which is then transformed into a work of art capable of seducing and completely captivating the observer.

The centrality that the sensations and emotions of the artist and the characters, as well as the portrayed landscapes, had conquered in the painting of the first decades of the 20th century, paved the way for research and expressive evolutions that transformed the execution of an artwork into a true revelation of all that inner feeling that individual painters were unable to manifest in everyday life; thus the subjectivity of the author permeated the canvas as much as his empathic strength in interpreting what the subject represented felt at the moment in which he became the conscious, or unconscious, protagonist of a painting that would give him eternity. Expressionism, the movement that focused most of all on the human being, almost becoming in some cases an extension of philosophical Existentialism, showed all the weaknesses of the individual in a historical period in which certainties were decaying, the hypocrisy of the aristocracy became evident especially in the face of the tragic events that were taking place in Europe, and where the appearance and attention to aesthetics of previous periods was no longer central to art; Egon Schiele was the leader of a look at the fragility of the human being, at the fears that translated into an obsession with a constantly manifested, almost obsessive sexuality, which concealed the need to find a way out of a sense of uncertainty and powerlessness in the face of external circumstances.

Just as much as Edvard Munch concentrated his pictorial research on the anxiety, the anguish of characters who at bottom were a reflection of all the difficulties and sorrows he had suffered since childhood, thus entrusting his protagonists with his own cry of pain. As the 20th century went on, the expressionist themes were broadened, turning into a gradually deeper, psychological analysis without ever losing their emotional impact, especially in that London School to which belonged immense representatives such as Lucian Freud, who with his corpulent naked bodies portrayed in intimate poses almost detached from everything that was going on around him succeeded in conveying the unease of living in a dehumanising age, Francis Bacon, with his images of distorted and disturbing faces resulting from the perception of a reality caused by the inner suffering that had always accompanied him, and finally Paula Rego and Michael Andrews, in whom Expressionism was less gloomy, more delicate and sometimes dreamy. The artist of Chinese origin, Xinyi Cheng, not only found his second home in Paris, but it was precisely in the French capital that she was able to develop and allow her pictorial research to evolve, thanks also to the possibility of easily travelling around Europe to visit the major museums from which she was able to draw inspiration and refine a style that from the very beginning showed an approach completely focused on the human being, on his feelings, on everything that is hidden in contingent reality but that instead appears evident to an inquiring sensibility. In fact, Xinyi Cheng takes her camera with her on every trip, even within Paris itself, catching small moments of the people she meets on her way, unconscious attitudes that stimulate her curiosity to the point of choosing to immortalise them and then interpret them with her expressive intensity.

The resulting works therefore constantly display an unreal atmosphere, as if the process of internalisation and revelation that then materialised on the canvas had decontextualised the subject from the environment in which he found himself at the moment of the encounter with Xinyi Cheng, as if what really counts is only the suspension that the inner feeling arouses both in the figure emanating the sensation, thus the protagonist of the painting, and in the author who receives the vibrations with which she envelops her pictorial gesture. Light is as unusual as it is variable in her paintings and is associated with the moment being narrated, so in some cases it simply emphasises a detail while in others it spreads to the entire canvas to the point of almost seeming to reach out to the surrounding environment, becoming a further element of communication with the observer. The feeling of unreality that envelops her characters seems to contrast with the ordinariness of their gestures, of their normality, almost as if for Xinyi Cheng it is there that everything that becomes extraordinary to her eyes is hidden, those poses and expressions that are apparently insignificant but that can constitute an extraordinary means of discovering the intensity of the characters and the essence that the artist is able to bring out.

During her time spent studying in the Netherlands, she produced a series of canvases dedicated to her homosexual friends, because one of the cornerstones of Cheng‘s artistic research is precisely the relationship of men with masculinity, with each one’s way of embracing their drives and their way of being, while digging deep into their feelings, regardless of their gender because what counts is revealing their essence, the instant in which they abandon themselves to the artist’s gaze. In these artworks, she did not make use of stolen shots but asked her models to pose, sometimes in their nudity, sometimes in surreal situations in which they had to let themselves go to fantasy and imagination, and it was precisely this moment that became the protagonist of a canvas; the artwork Stijn in the red bonnet is symbolic of this part of Xinyi Cheng‘s production, and narrates the insecurity, the fear of the protagonist who is perhaps regretting having agreed to choose that very strange bonnet, or perhaps instead is simply recalling an episode during which he did not feel comfortable bringing it back to the present moment.

Everything seems to be mysterious in Cheng‘s atmospheres, precisely because she does not want to give an unambiguous answer, rather she tends to provide a range of interpretative possibilities of which each individual observer will be the first actor, who will decline them on the basis of his own unique sensitivity. Cigarettes are often co-protagonists in her canvases, almost as if the gesture of smoking emphasises the suggestion that the artist entrusts to the characters, almost as if in front of that simple act everything becomes more interesting, more fascinating; in the painting For a Light II, the two young people seem to be in the process of telling updates on their lives, or on the contrary they are simply two strangers who have found each other by chance outside a club to take a break and probably have nothing in common except their passion for cigarettes.

This is what is so striking about Cheng‘s work, the impossibility of giving a well-defined location and meaning to the scenes and characters described, as space and time seem to be suspended, the men and women enigmatic, caught within their own world that they recount without revealing, arousing that impulse to carry out an introspective search that too often in contemporary life is neglected to make room for materialism and the urgency of achieving goals. Xinyi Cheng, on the other hand, pauses, takes a breath and meditates, highlighting everything that belongs to the human being, everything that concerns that everyday life that basically represents life. Xinyi Cheng has solo museum exhibitions to her credit at the Hamburger Bahnhof in Berlin, and Lafayette Anticipations in Paris, and has taken part in group exhibitions at the Palais de Tokyo in Paris, the Renaissance Society in Chicago, the Thirteenth Shanghai Biennial and the Stock Exchange in Paris.