Il mondo contemporaneo è senza dubbio globalizzato e tendente verso la conoscenza di tutto ciò che è distante dalla cultura di origine, proprio in virtù della facilità di spostamento e di comunicazioni che nel passato sembrava impensabile da realizzare; questo dà la possibilità agli artisti che si sentono attratti dalla scoperta, dalla conoscenza di tradizioni, di modi di vita e di paesaggi completamente differenti dal proprio, di dedicare la loro produzione alla descrizione, che è anche esplorazione, di quei luoghi lontani. L’artista di cui vi racconterò oggi conduce invece l’osservatore all’interno della semplicità, della profondità e del desiderio di contatto con i popoli, molto più che i luoghi, con quei volti incrociati per caso che rende protagonisti delle sue tele.

Già a partire dal Sedicesimo secolo, con le conquiste coloniali e il contatto con culture differenti da quella europea, vi fu nell’arte, come anche nella letteratura e nella cultura in genere, un’attrazione verso la novità costituita da forme, ornamenti e raffigurazioni che provenivano sia dall’estremo Oriente sia dal mondo arabo; quest’attrazione si trasformò in decorazione di intere stanze degli edifici nobiliari di cui farsi vanto con gli ospiti dei palazzi. Fu però nell’Ottocento, dopo il Romanticismo, che l’arte cominciò a occuparsi in maniera più completa e descrittiva della malia che l’esotismo generava nei pittori come anche nei fruitori e nei collezionisti; indimenticabili le opere dell’Espressionismo di Paul Gauguin, legato a Tahiti, che nello stesso periodo si affiancarono all’attenzione nei confronti del Primitivismo, manifestazione pittorica e scultorea in cui si rappresentavano e riproducevano le maschere africane e indigene delle varie colonie europee che furono di ispirazione per la produzione dei maggiori artisti dell’epoca. A partire dal Naif di Henri Rousseau, in cui i luoghi erano immaginati, sognati, più che frutto di una conoscenza personale, fu poi il Cubismo di Pablo Picasso a introdurre in maniera incisiva le iconografie delle maschere africane nei volti delle sfaccettate donne protagoniste delle sue tele, proseguendo poi con le figure scultoree e pittoriche di Amedeo Modigliani in cui si generava una mescolanza tra cultura esotica ed europea, in perfetta armonia stilistica. Alcuni espressionisti, come Ernst Ludwig Kirchner si posero in posizione critica rispetto al colonialismo, evidenziando la naturalezza della libertà di costumi delle civiltà primitive come un esempio da seguire dalla corrotta e superficiale borghesia del Vecchio Continente in cui i valori si erano completamente disgregati davanti alla falsità e all’ipocrisia che ne contraddistingueva le dinamiche di vita. Emil Nolde al contrario, ebbe un approccio più scientifico e al tempo stesso rapito nei confronti dei mondi lontani, delle abitudini, delle forme osservate durante i suoi viaggi in Oriente. Tutti in ogni caso determinarono e affermarono l’esigenza di conoscere e scoprire le differenze di culture, di tradizioni e di modi di vivere misteriosi ed enigmatici proprio perché diversi. L’artista abruzzese Barbara Berardicurti, da anni ormai residente a Roma, svela nelle sue opere tutto il fascino che esercita su di lei la diversità, il desiderio di entrare in contatto con popoli nati e cresciuti in mondi lontani, in cui il modo di vestire, di approcciare l’esistenza, di affrontare la quotidianità è talmente distante dal suo da indurla a cercare ed evidenziare l’essenza, oltre che la forma, dei volti i cui sguardi la colpiscono al punto di indurla a ritrarli, a renderli protagonisti delle sue tele.

Non c’è solo curiosità nelle opere della Berardicurti, bensì la tendenza empatica a comprendere le sensazioni, gli stati d’animo pur legandoli imprescindibilmente al contesto a cui appartengono, svelando all’osservatore da un lato la vicinanza e la similitudine delle emozioni che assumono così un senso universale, ma dall’altro il profondo legame con la terra di appartenenza di ciascun personaggio, quel mondo in cui le vite si svolgono e che in qualche modo determina e condiziona le abitudini, le conoscenze acquisite, le consuetudini quotidiane.

Attraverso lo sguardo dell’artista emerge un rispetto assoluto per quelle differenze, un invito a non voler modificare e occidentalizzare le persone e i luoghi raccontati piuttosto a scoprirne la bellezza nel loro contesto naturale, nella calma serenità di un’esistenza che non conosce la fretta, l’arrivismo, la corsa all’accumulo che contraddistingue invece la nostra cultura contemporanea. Barbara Berardicurti infonde nei volti narrati tutta la naturalezza e lo stupore nel sentirsi protagonisti di tanta attenzione, eppure un attimo dopo si lasciano andare e mostrano la loro vera essenza, come se si sentissero a proprio agio in virtù dell’apertura all’ascolto davanti a cui si trovano, in grado di trasparire dal tocco leggero e impalpabile della capacità espressiva dell’artista.

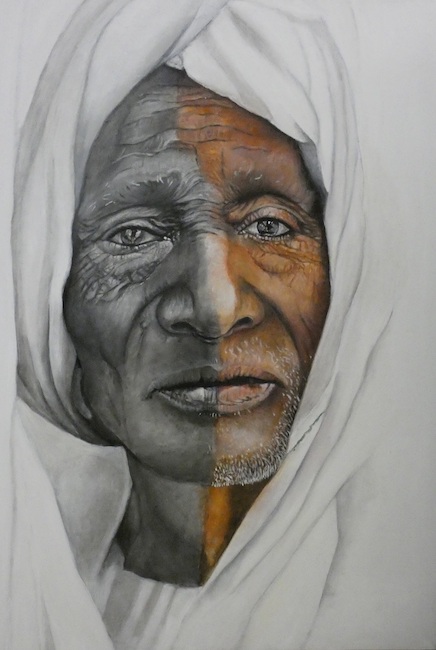

Africa e Asia sono i paesi da cui si sente più attratta, dalla capacità dei loro abitanti di acquisire saggezza e consapevolezza in maniera ben più radicata e spirituale rispetto alla spesso superficiale esistenza occidentale; nella tela The light in the eyes (La luce negli occhi) l’anziano uomo nordafricano sembra nascondere nel fondo dei suoi occhi, che guardano fieri l’osservatore, i paesaggi che hanno lungamente scrutato, la precarietà della povertà che conserva comunque sempre una radicata dignità, mettendo in risalto quanto in fondo sia possibile costruire tutto anche con poco, e che la sostanza, quella vera, non è data dai possedimenti materiali bensì dal percorso dello spirito. Gioca con la scala di grigi e il colore la Berardicurti, sottolineando in tal modo quanto non vi sia differenza nella forma esteriore, nella razza o nella religione, nella luce o nell’ombra, se l’animo viene coltivato ed elevato verso la conoscenza e l’accettazione di tutto ciò che fa parte della vita.

Il medesimo effetto visivo si ripete anche nell’opera Keibrà, fierezza in cui la donna protagonista si mostra senza timore o timidezza all’artista che la sta ritraendo, come se attraverso i suoi occhi volesse lasciar trapelare la serenità e l’orgoglio di appartenere a una cultura secolare, che tramanda le sue tradizioni mantenendole pure, inalterate dal passare dei tempi e orientate a dare valore all’individuo, all’essere umano, al senso di comunità che contraddistingue i popoli orientali. Dunque il colore rappresenta la consapevolezza, ciò che appartiene al visibile, al tangibile e così l’aspetto esterno si mescola alla parte in bianco e nero, quella di una più profonda connessione con il passato, con l’eredità degli avi, con l’equilibrio che viene da una lunga scia di usi e costumi trasmessi nel tempo.

In Alternanza indissolubile la Berardicurti esplora la spontaneità di una donna africana che si mostra con tutta la sua dolcezza, nel pieno della sua giovane vita, avvolta da una gonna leggera e impalpabile che riprende il tema della tenda dietro di lei; non vi è insoddisfazione nel suo sguardo, piuttosto una morbida curiosità nei confronti dell’artista per cui sta posando, forse inconsapevole che il suo volto sarà consacrato all’immortalità della tela. Ciò che emerge in maniera nitida in questo dipinto è il naturale ciclo dell’esistenza, quel nascere e poi morire a cui è necessario rassegnarsi, che è impossibile non accettare, ed è proprio per questo che vivere pienamente tutto ciò che c’è nel mezzo diventa l’imperativo sostanziale, quell’assaporare ciascun frangente, ciascun attimo, che contraddistingue le popolazioni più tribali, meno evolute forse ma non per questo meno felici nel senso più completo del termine.

Stupore e affascinante narrazione nel rispetto delle culture altre dalla propria sono il tratto distintivo di Barbara Berardicurti, che utilizza sapientemente il bianco e nero per evidenziare dettagli o intere parti di scena come nel dipinto Mercato Sapa, in cui racconta tre donne in abito tradizionale di quella specifica tribù del Vietnam, i Sapa appunto, nella loro tranquilla spontaneità, nella genuinità con cui affrontano un evento ripetuto nel tempo e fonte di quegli usi che vengono da lontano. Artista da sempre Barbara Berardicurti è socia ordinaria dell’Associazione Cento Pittori di via Margutta e dell’Associazione Alternativa 94 work in progress, ha ricevuto molti premi e riconoscimenti e ha partecipato a innumerevoli mostre collettive in Italia e all’estero – Mosca, Londra, Boston -.

BARBARA BERARDICURTI-CONTATTI

Email: berardicurti@gmail.com

Sito web: www.barbaraberardicurti.eu

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/barbara.berardicurti

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/berardicurtibarbara/

Exotic fascination and the desire to discover the customs and traditions of faraway peoples in Barbara Berardicurti’s artworks

The contemporary world is undoubtedly globalised and tends towards knowledge of everything that is distant from the culture of origin, precisely because of the ease of movement and communication that in the past seemed unthinkable to achieve. This gives artists who feel attracted by discovery, by knowledge of traditions, ways of life and landscapes completely different from their own, the opportunity to devote their production to the description, which is also exploration, of those distant places. The artist I am going to tell you about today, on the other hand, leads the observer into the simplicity, depth and desire for contact with peoples, much more than with places, with those faces crossed by chance that she makes the protagonists of her canvases.

As early as the sixteenth century, with the colonial conquests and contact with cultures different from the European one, there was an attraction in art, literature and culture in general towards the novelty of forms, ornaments and representations from the Far East and the Arab world; this attraction was transformed into decorating entire rooms in noble buildings and boasting about it to the guests of the palaces. However, it was in the 19th century, after Romanticism, that art began to deal more fully and descriptively with the enchantment that exoticism generated in painters as well as in users and collectors; the unforgettable works of Paul Gauguin’s Expressionism, linked to Tahiti, in the same period were accompanied by the attention paid to Primitivism, a pictorial and sculptural manifestation in which African and indigenous masks from the various European colonies were represented and reproduced, and which inspired the production of the major artists of the time.

Starting with Henri Rousseau’s Naif, in which places were imagined, dreamt of, rather than the result of personal knowledge, it was then Pablo Picasso’s Cubism that incisively introduced the iconography of African masks into the faces of the multi-faceted women protagonists of his canvases, continuing with Amedeo Modigliani’s sculptural and pictorial figures in which a mixture of exotic and European culture was generated, in perfect stylistic harmony. Some Expressionists, such as Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, were critical of colonialism, highlighting the natural freedom of customs of primitive civilisations as an example to be followed by the corrupt and superficial bourgeoisie of the Old World in which values had completely disintegrated in the face of the falsehood and hypocrisy that characterised the dynamics of life. Emil Nolde, on the other hand, had a more scientific and at the same time enraptured approach to the distant worlds, customs and forms observed during his travels in the East. In any case, they all determined and affirmed the need to know and discover the differences in cultures, traditions and ways of living that are mysterious and enigmatic precisely because they are different. Barbara Berardicurti, an artist from Abruzzo who has been living in Rome for many years, reveals in her artworks all the fascination that diversity exerts on her, the desire to come into contact with peoples born and raised in distant worlds, where the way of dressing, of approaching life, of the way of living, of the way of thinking, of the way of living, whose way of dressing, of approaching life, of facing everyday life is so distant from her own that she seeks out and highlights the essence, as well as the form, of the faces whose gazes strike her to the point of making her portray them, making them the protagonists of her canvases.

There is not only curiosity in Berardicurti’s works, but also an empathic tendency to understand the sensations and moods, linking them inextricably to the context to which they belong, revealing to the observer on the one hand the closeness and similarity of the emotions, which thus take on a universal meaning, and on the other hand the profound bond with the land to which each character belongs, the world in which their lives take place and which in some way determines and conditions their habits, acquired knowledge and daily customs. Through the artist’s gaze emerges an absolute respect for these differences, an invitation not to modify and westernise the people and places portrayed, but rather to discover their beauty in their natural context, in the calm serenity of an existence that does not know the haste, the careerism, the race to accumulate that characterises our contemporary culture. Barbara Berardicurti infuses the faces she narrates with all the naturalness and astonishment of feeling that they are the protagonists of so much attention, and yet a moment later they let themselves go and show their true essence, as if they feel at ease by virtue of the openness to listening before which they find themselves, able to transpire from the light and impalpable touch of the artist’s expressive capacity. Africa and Asia are the countries from which she feels most attracted, by the ability of their inhabitants to acquire wisdom and awareness in a far more rooted and spiritual manner than the often superficial western existence; in the canvas The light in the eyes, the elderly North African man seems to hide in the depths of his eyes, which look proudly at the observer, the landscapes he has long scanned, the precariousness of poverty which nevertheless always preserves a deep-rooted dignity, highlighting how it is possible to build everything with little, and that the substance, the real substance, is not given by material possessions but by the path of the spirit. Berardicurti plays with greyscale and colour, emphasising how there is no difference in external form, race or religion, light or shade, if the soul is cultivated and elevated towards knowledge and acceptance of all that is part of life.

The same visual effect is repeated in the work Keibrà, pride, in which the woman in the leading role shows herself without fear or shyness to the artist who is portraying her, as if through her eyes she wanted to reveal the serenity and pride of belonging to a centuries-old culture, which has handed down its traditions, keeping them pure, unaltered by the passing of time and oriented towards giving value to the individual, to the human being, to the sense of community that distinguishes oriental peoples. So colour represents awareness, that which belongs to the visible, to the tangible, and so the external aspect is mixed with the black and white part, that of a deeper connection with the past, with the heritage of the ancestors, with the balance that comes from a long trail of customs and traditions transmitted over time. In Alternanza indissolubile (Unbreakable alternation), Berardicurti explores the spontaneity of an African woman who shows herself in all her sweetness, in the prime of her young life, wrapped in a light, impalpable skirt that picks up the theme of the curtain behind her; there is no dissatisfaction in her gaze, rather a soft curiosity towards the artist for whom she is posing, perhaps unaware that her face will be consecrated to the immortality of the canvas. What emerges clearly in this painting is the natural cycle of existence, that birth and then death to which one must resign oneself, which it is impossible not to accept, and it is precisely for this reason that living fully all that there is in between becomes the essential imperative, that savouring of each juncture, each moment, which distinguishes the most tribal populations, less evolved perhaps but no less happy in the fullest sense of the term. Barbara Berardicurti’s distinctive trait is astonishment and fascinating narration with respect for cultures other than her own. She skilfully uses black and white to highlight details or entire parts of the scene, as in the painting Sapa Market, in which she depicts three women in traditional dress from that specific tribe in Vietnam, the Sapa, in their quiet spontaneity, in the genuineness with which they face an event repeated over time and the source of those customs that come from afar. Barbara Berardicurti has always been an artist and is a member of the Associazione Cento Pittori di via Margutta and of the Associazione Alternativa 94 work in progress. She has received many prizes and awards and has taken part in many collective exhibitions in Italy and abroad – Moscow, London, Boston.