Il vasto e variegato panorama dell’espressione artistica contemporanea rappresenta un’evoluzione ma anche una somma dei movimenti artistici che hanno caratterizzato il secolo scorso, pur mostrando la tendenza dei creativi a oltrepassare i confini che ciascuna corrente usava per distinguersi dalle altre; generare una sintesi e un arricchimento dei limiti emersi soprattutto nei casi in cui la trasformazione e l’adeguamento a filosofie e tematiche differenti era stata pressoché impossibile, appartiene agli artisti contemporanei tanto quanto per alcuni di loro diviene essenziale mantenere intatte le differenze stilistiche che contraddistinguono i diversi approcci pittorici senza mescolarle e sintetizzarle bensì utilizzandole sulla base del messaggio o dell’emozione che desiderano liberare. Il protagonista di oggi vive l’arte nel mondo dell’astratto pur necessitando di spostarsi su diversi livelli dello stesso ambito per osservare e raccontare le emozioni umane.

L’Astrattismo fu un movimento rivoluzionario che investì il mondo dell’arte dei primi decenni del Novecento, quando il distacco dalle regole accademiche e dalla figurazione classicamente intesa si impose come obiettivo la ricerca di una modalità differente di dipingere e di scolpire, modalità più libera, meno legata alla realtà così come osservata, sicuramente trasformata dal filtro emotivo o mentale dell’esecutore dell’opera. Già con il Cubismo e con il Futurismo la scomposizione dell’immagine divenne essenziale per infondere uno sguardo originale, sfaccettato, multifocale su tutto ciò che davanti agli occhi si presentava, derogando così completamente dalla raffigurazione come classicamente intesa; con il proseguire del percorso di sperimentazione, a seguito ma anche a causa della sempre maggiore diffusione della nuova tecnologia di rappresentazione della realtà, la fotografia, un nutrito gruppo di artisti decise di voler affermare la supremazia assoluta del gesto plastico, dell’atto creativo, su ogni tipo di emozionalità, di sensazione e soprattutto dell’immagine conosciuta concludendo che solo quel modo di esprimersi potesse essere definito pura arte. Il De Stijl, movimento in cui queste linee guida furono enfatizzate ed estremizzate trovò ben presto il limite autoindotto dai suoi fondatori, Piet Mondrian e Theo Van Doesburg, relativo alla scelta delle sole linee rette e dei colori primari che indussero alcuni esponenti a distaccarsi dalle rigide regole e avvicinarsi al nascente Astrattismo Geometrico decisamente più aperto ad accogliere sia una gamma più vasta di colori sia le forme tondeggianti. La caratteristica dell’Astrattismo Geometrico, così come dei successivi movimenti della Bauhaus e della Op Art, fu l’esplorazione razionale e mentale sulla tecnica esecutiva, sull’effetto ottico delle opere, sulla pura ricerca nei confronti del colore e delle forme che erano base imprescindibile della tela stessa e che attraverso la loro intersecazione davano un senso differente alla realtà osservata. Oltreoceano però fu evidenziato il completo distacco dal mondo emozionale di quelle correnti artistiche e si andò così alla ricerca di un superamento di quella lontananza dal coinvolgimento dell’osservatore attraverso l’Espressionismo Astratto in cui tutto ciò che contava era l’impulso creativo e la sensazione dell’artista a discapito di qualsiasi regola esecutiva.

L’artista francese Francois Bianchi sceglie volutamente il linguaggio dell’Astrattismo non mescolando o sintetizzando i vari movimenti che hanno segnato il secolo scorso bensì avvicinandosi all’uno o all’altro sulla base della sua necessità espressiva, ascoltando l’estro creativo che lo porta a misurarsi con una parte più impulsiva, più emozionale, e in quel caso propende per l’Espressionismo Astratto, oppure con quella più meditata, mentale, dando vita a opere più vicine alla Op Art oppure ai lavori grafici in sile Bauhaus del maestro Josef Albers.

Ciò che contraddistingue la produzione di Bianchi è la sua tendenza all’osservazione e all’ascolto generata dalla capacità innata di assorbire dettagli e sensazioni del mondo in cui si muove e che costituisce per lui una continua scoperta, una costante fonte di approfondimento non solo di ciò che è esterno a sé bensì anche di ciò che appartiene alla sua essenza e che si modifica in virtù, e spesso anche a causa, degli accadimenti. Ed è proprio grazie a questa apertura all’interazione, al reciproco scambio, che l’artista decide di raccontare quelle riflessioni che appartengono all’essere umano e che si sviluppano mettendosi in ascolto dei singoli dettagli che appaio fugaci e che riescono a catturare l’attenzione dell’osservatore attivando un concatenamento emotivo spesso irrazionale ma tuttavia di forte impatto.

La tela Éclat (Bagliore), in pieno stile espressionista astratto descrive un istante in cui qualcosa si verifica, un particolare colto dallo sguardo e che incuriosisce la mente la quale si domanda da cosa possa essere generato il bagliore di cui parla il titolo; dunque la prima fase istintiva non può fare a meno di collegarsi e riflettersi su quella razionale che in qualche modo è stimolata a trovare la fonte, la causa dell’effetto percepito dall’occhio. Nelle opere di questa serie Francois Bianchi si muove sui toni di grigio a cui aggiunge il rosso che ha il significato della rottura di uno schema, dell’indicare quell’improvviso che si manifesta quotidianamente e che scuote il torpore dell’ordinarietà per indurre l’individuo ad aprirsi e accogliere anche ciò che in qualche modo destabilizza perché è comunque funzionale alla scoperta di un nuovo sé.

In Énigme (Enigma) l’artista rafforza questo concetto, quello dell’umana necessità di interrogarsi sulla realtà circostante e i segreti che cela, in virtù dei quali la mente si spinge verso la comprensione, verso il dubbio essenziale per una conoscenza via via maggiore; l’enigma d’altro canto può essere anche quello esistenziale, la direzione verso cui tendere in una contemporaneità disorientante da osservare con sguardo critico, considerando le sue stratificazioni, i suoi diversi livelli rappresentati da Bianchi attraverso pennellate orizzontali, grosse linee parallele attraversate in alcuni tratti da segmenti di colore indicanti, in questo caso, i dettagli a cui aggrapparsi per intravedere la risoluzione del mistero del vivere.

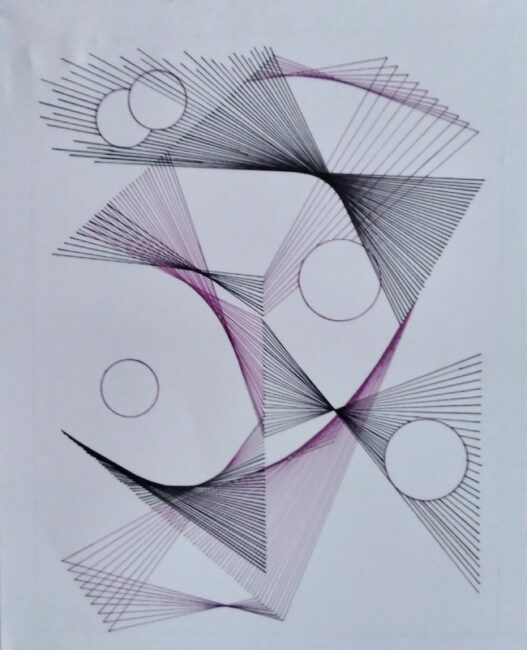

Parallelamente alla produzione più legata all’Espressionismo Astratto l’artista sente però il bisogno di misurarsi anche con un approccio più mentale, più sperimentale e scientifico, come nell’opera Transition (Transizione) che si avvicina all’Op Art degli anni Sessanta e Settanta del Novecento, in cui l’effetto ottico era la base di ricerca degli artisti aderenti e in cui lo studio verteva sull’effetto dell’illusione bidimensionale che riusciva a infondere sull’osservatore la sensazione di movimento introducendo della terza dimensione che di fatto era generata solo dalla sapiente modulazione grafica delle figure scelte per eseguire la rappresentazione grafica. In questo lavoro Francois Bianchi pone in dialogo i volumi geometrici e la leggerezza delle linee come momento di trasformazione da una solida certezza verso l’instabilità delle regole che determinano l’esistenza, o viceversa, da una fase in cui tutto sembra essere incerto e impalpabile si può passare a un’altra in cui invece l’esperienza conduce a una maggiore sicurezza e comprensione della necessità di costruire un microcosmo all’interno del quale sentirsi protetti, saldamente ancorati agli elementi essenziali della propria vita.

Francois Bianchi ama misurarsi anche con la scultura, mantenendo sempre il suo legame con il mondo dell’Astrattismo, che in questo caso diviene ancor più concettuale come nella leggera opera L’heure du temps (L’ora del tempo) con cui l’artista esplora il concetto del tempo attraverso lo strumento di regolazione di esso, l’orologio, collegandolo però a ruote a raggera, simili a quelle delle biciclette, sottintendendo quanto sia fondamentale considerare la sua fuggevolezza, la velocità con cui l’esistenza intera si svolge malgrado l’umana convinzione che sia possibile fare tutto prima o poi, rimandando a volte questioni importanti, decisioni essenziali, che poi potrebbero non essere più prese.

Recentemente contrattualizzato in esclusiva dall’Hippodrome de grand Genève de Divonne les Bains per creare sculture per i trofei per i vincitori delle corse e per le cerimonie di premiazione, Francois Bianchi ha fatto parte per molti anni dell’Associazione Art’s Club di Thoiry di cui è stato anche Presidente dal 2018 al 2019 e le sue opere sono molto apprezzate dal pubblico e dalla critica.

FRANCOIS BIANCHI-CONTATTI

Email: francoisbianchi.art@gmail.com

Sito web: https://www.francoisbianchi.com/fr-fr/index.html

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/francois.bianchi.7

Francois Bianchi, observing the world and human emotions through the different nuances of Abstractionism

The vast and varied panorama of contemporary artistic expression represents an evolution but also a summation of the artistic movements that characterized the last century, while showing the tendency of creatives to transcend the boundaries that each current used to distinguish from the others; generating a synthesis and enrichment of the limits that have emerged, especially in cases where transformation and adaptation to different philosophies and themes had been almost impossible, belongs to contemporary artists just as much as for some of them it becomes essential to keep intact the stylistic differences that distinguish the different pictorial approaches without mixing and synthesising them but using on the basis of the message or emotion they wish to release. Today’s protagonist experiences art in the world of the abstract while needing to move to different levels of the same field to observe and narrate human emotions.

Abstractionism was a revolutionary movement that swept through the art world in the early decades of the 20th century, when detachment from the academic rules and from classically understood figuration imposed itself as objective the search for a different way of painting and sculpting, a freer way, less tied to reality as observed, certainly transformed by the emotional or mental filter of the work’s executor. Already with Cubism and Futurism, the decomposition of the image became essential in order to instil an original, multifaceted, multifocal gaze on everything that appeared before the eyes, thus making a complete departure from representation as classically understood; with the continuation of experimentation, following but also due to the ever-increasing diffusion of the new technology of representation of reality, photography, a large group of artists decided they wanted to affirm the absolute supremacy of the plastic gesture, of the creative act, over every type of emotion, sensation and above all the known image, concluding that only that way of expressing themselves could be defined as pure art. De Stijl, a movement in which these guidelines were emphasised and taken to extremes, soon came up against the self-induced limitation of its founders, Piet Mondrian and Theo Van Doesburg, regarding the choice of only straight lines and primary colours, which led some exponents to break away from the rigid rules and approach the nascent Geometric Abstractionism, decidedly more open to accept both a wider range of colours and rounded forms. The characteristic of Geometric Abstractionism, as well as of the subsequent Bauhaus and Op Art movements, was the rational and mental exploration of the technique of execution, of the optical effect of the works, of the pure research into the colours and shapes that were the essential basis of the canvas itself and that through their intersection gave a different sense to the reality observed.

On the other side of the Atlantic, however, was highlighted the complete detachment from the emotional world of those artistic currents and the search was launched to overcome that distance from the observer’s involvement through Abstract Expressionism in which all that mattered was the creative impulse and the artist’s sensation to the detriment of any executive rule. The French artist Francois Bianchi deliberately chooses the language of Abstractionism not by mixing or synthesising the various movements that have marked the last century but by approaching one or the other on the basis of his expressive needs, listening to his creative inspiration that leads him to measure himself with a more impulsive, emotional side, in which case he tends towards Abstract Expressionism, or with a more meditated, mental side, giving life to works closer to Op Art or to the graphic works in the Bauhaus style of the master Josef Albers. What distinguishes Bianchi’s work is his tendency to observe and listen, generated by his innate ability to absorb details and sensations from the world in which he moves.

For him, this constitutes a continuous discovery, a constant source of investigation not only of what is external to him but also of what belongs to his essence and is modified by virtue of, and often because of, events. And it is thanks to this openness to interaction, to mutual exchange, that the artist has decided to recount those reflections that belong to the human being and that develop by listening to the single details that appear fleeting and manage to capture the observer’s attention, activating an emotional chain that is often irrational but nevertheless of great impact. The canvas Éclat, in full Abstract Expressionist style, describes an instant in which something occurs, a detail caught by the eye that intrigues the mind, which wonders from what the glow referred to in the title can be generated; thus the first instinctive phase cannot fail to connect and reflect on the rational one, which in some way is stimulated to find the source, the cause of the effect perceived by the eye. In the artworks of this series, Francois Bianchi uses shades of grey, to which he adds red, which signifies the breaking of a pattern, indicating the suddenness that manifests itself on a daily basis and shakes off the torpor of ordinariness to induce the individual to open up and welcome even that which in some way destabilises because it is in any case functional to the discovery of a new self. In Énigme the artist reinforces this concept, that of the human need to question oneself about the surrounding reality and the secrets it conceals, by virtue of which the mind moves towards understanding, towards the doubt that is essential for ever greater knowledge; the enigma, on the other hand, can also be existential, the direction towards which we must tend in a disorienting contemporaneity to be observed with a critical eye, considering its stratifications, its different levels represented by Bianchi through horizontal brushstrokes, large parallel lines crossed in some places by segments of colour indicating, in this case, the details to hold on to in order to glimpse the resolution of the mystery of living.

In parallel with his work more closely linked to Abstract Expressionism, however, the artist also felt the need to measure himself against a more mental, experimental and scientific approach, as in the artwork Transition, which comes close to the Op Art of the 1960s and 1970s, in which the optical effect was the basis of the artists’ research and in which the study focused on the effect of the two-dimensional illusion that succeeded in instilling in the observer the sensation of movement by introducing a third dimension that was in fact only generated by the skilful graphic modulation of the figures chosen to perform the graphic representation. In this artwork Francois Bianchi places geometric volumes and the lightness of lines in dialogue as a moment of transformation from a solid certainty towards the instability of the rules that determine existence, or vice versa, from a phase in which everything seems to be uncertain and impalpable one can pass to another in which instead experience leads to greater security and understanding of the need to build a microcosm within which to feel protected, firmly anchored to the essential elements of one’s life. Francois Bianchi also likes to measure himself against sculpture, always maintaining his link with the world of Abstractionism, which in this case becomes even more conceptual, as in the light work L’heure du temps, in which the artist explores the concept of time through the instrument that regulates it, the clock, connecting it, however, to spoked wheels, similar to those on bicycles, implying how fundamental it is to consider its fleeting nature, the speed with which all of existence takes place, despite the human conviction that it is possible to do everything sooner or later, sometimes postponing important questions, essential decisions, which may never be taken again. Recently contracted exclusively by the Hippodrome de grand Genève de Divonne les Bains to create sculptures for the trophies for the winners of the races and for the prize-giving ceremonies, Francois Bianchi has taken part for many years of the Art’s Club of Thoiry, of which he has been President from 2018 til 2019, and his artworks are highly appreciated by the public and the critics.