Il modo di rappresentare tutto ciò che appartiene al paesaggio naturale svela l’attitudine di ciascun artista, sia dal punto di vista stilistico che da quello del sentire, poiché l’interpretazione che viene data a ciò su cui lo sguardo si sofferma nell’atto della contemplazione riesce a far trapelare l’approccio alla vita, e di conseguenza al messaggio che dalle sue opere deve fuoriuscire giungendo in maniera diretta all’osservatore. A volte il panorama si assoggetta alle sensazioni più interiori lasciando che sia l’interiorità a determinare l’aspetto finale della tela, altre invece il desiderio di riprodurre in maniera fedele la bellezza di fronte a sé diviene la linea guida principale, pur raccontando al contempo il trasporto poetico che l’autore vive nell’atto del dipingere. L’artista di cui vi racconterò oggi ha descritto paesaggi sereni, luminosi, pieni di calma e di armonia con uno stile raffinato e di grande impatto visivo proprio in virtù di un punto di vista estetico ma al tempo stesso emozionale.

La pittura di paesaggio, considerata almeno fine a tutto il Settecento di secondo ordine rispetto al ritratto o ai soggetti religiosi commissionati dalla Chiesa, vide nei primi decenni dell’Ottocento un crescente interesse negli ambienti culturali che contavano, stimolato dalle meravigliose e suggestive opere del Romanticismo Inglese dove i panorami quasi privi della presenza dell’uomo riuscivano a sottolineare il ruolo di primo piano che i luoghi che da sempre ospitano la vita dovrebbero avere anche in virtù della dirompente forza o di un equilibrio in grado di sopravvivere nei secoli. Il sublime di William Turner e il pittoresco della riproduzione della delicata campagna britannica di John Constable aprirono la strada al diffondersi del genere paesaggistico come scelta da parte di molti creativi che prediligevano osservare ciò che accadeva intorno a sé piuttosto che concentrarsi sugli interni o sui ritratti, sicuramente più ambìti dai committenti ma decisamente più limitanti dal punto di vista visivo. L’intuizione iniziale dei romantici proseguì soprattutto in Italia con la Scuola di Posillipo e con i Macchiaioli toscani che si concentrarono su una maggiore precisione nella descrizione dei luoghi immortalati e su un utilizzo pieno della luce, come se quest’ultima fosse a sua volta protagonista indiscussa delle scene e dei panorami su cui verteva la produzione artistica degli appartenenti a queste due scuole pittoriche. Il consolidamento dell’importanza della rappresentazione della natura avvenne più tardi, verso la fine del Diciannovesimo secolo, con l’affermarsi di un nuovo stile in cui venne introdotta l’impressione di bellezza, di equilibrio estetico e di incanto della luce che l’artista riceveva davanti ai paesaggi che si apprestava a riprodurre, facendo emergere così l’esigenza di iniziare e terminare l’opera nell’arco di poche ore, prima di perdere il contatto con la magia che si trovava di fronte allo sguardo dell’autore. Mancanza di disegno preparatorio, utilizzo del colore prendendolo direttamente dai tubetti, non mescolato sulla tavolozza come da tradizione, e il suo accostamento sulla tela con brevi pennellate per impressionare la retina dell’osservatore che riceveva la visione generale solo allontanandosi dall’opera, furono caratteristiche imprescindibili dell’Impressionismo che aprì la strada al concetto di frammentazione del colore direttamente sul supporto scelto, più tardi ripreso e ampliato, proprio dal punto di vista della luce, dal successivo Divisionismo. Malgrado l’attitudine di partenza fosse essenzialmente estetica, sia nel caso dell’Impressionismo che in quello del Divisionismo è impossibile non notare quanto la bellezza sia in grado di muovere le corde poetiche dell’interiorità, le stesse che vibrano davanti ai paesaggi dell’artista emiliano Vladimiro Tomasi, scomparso nel 2011, che ha narrato i luoghi a lui più cari sotto diversi punti di vista, tutti però contraddistinti da una calma armonia e da un sapiente quanto suggestivo utilizzo della luce, a volte persino protagonista delle sue tele, come se senza di essa ci si trovasse davanti a una melodia con la nota principale mancante.

In lui da un lato emerge la necessità di frammentare il colore per utilizzarlo in purezza permettendo che esso si mescoli solo nello sguardo dell’osservatore, avvicinandolo così all’Impressionismo, dall’altro si evidenzia una tendenza alla riproduzione fedele dell’osservato che lo spinge verso il Verismo con l’approccio alla luce che aveva contraddistinto il Divisionismo di Giovanni Segantini.

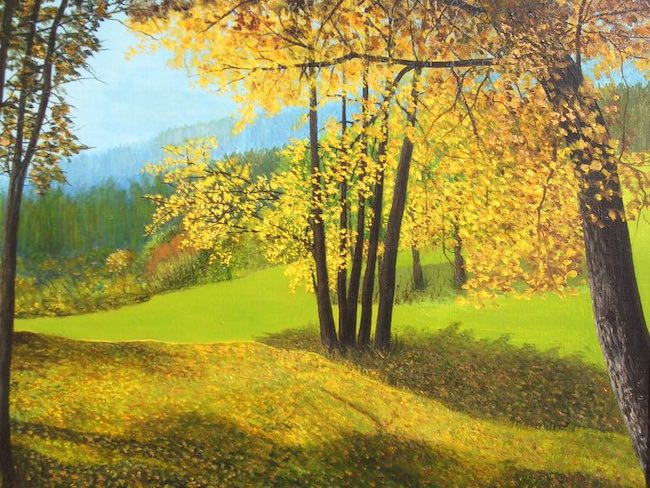

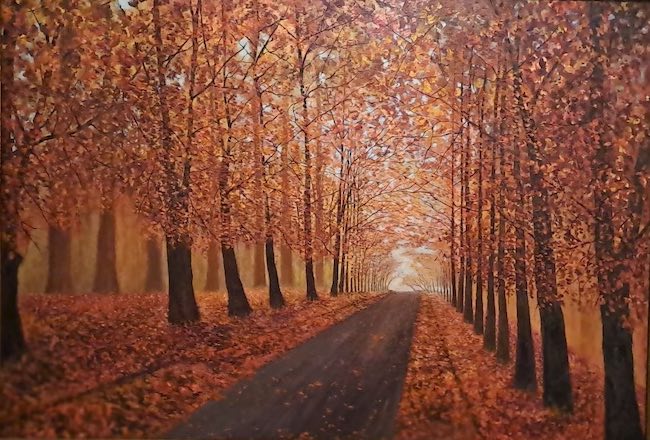

Ma più di tutto le sue tele sono permeate dall’ammirazione di Vladimiro Tomasi nei confronti dei luoghi, degli scorci che in qualche modo hanno colpito il suo gusto estetico fino a giungere a muovere le sue emozioni inducendolo a immortalare tutta la bellezza di fronte a sé attraverso la sua pittura, dando così vita a dipinti di perfetto equilibrio formale, in cui ogni particolare, ogni dettaglio è co-protagonista del risultato finale.

Il rigore nella descrizione degli edifici, l’apparato prospettico impeccabile, si associano alla morbidezza descrittiva della natura, in cui il tratto esce dal Verismo per entrare in un Impressionismo poetico che non può fare a meno di trasportare l’osservatore in quel mondo magico del ricordo visivo dell’artista. La caratteristica principale e più evidente è la luminosità che pervade ogni opera di Vladimiro Tomasi, persino quelle meno solari presentano un chiarore dominante che contribuisce a mostrare l’approccio positivo alla vita di un autore che ha votato la sua intera esistenza alla pittura.

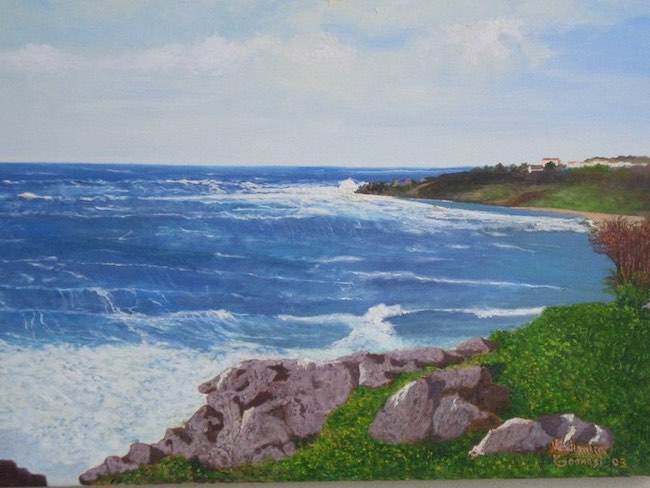

La tela Mareggiata a Masua è emblematica del suo stile pittorico e dell’importanza della luce perché il chiarore riesce a illuminare persino il cielo pieno di nuvole, quasi come se il colore dell’acqua agitata dalle onde fosse in grado di riflettersi e illuminare ciò che è sopra di lei; il movimento del mare è evidente ma non ha un’apparenza minacciosa, burrascosa, anzi sembra sia nella fase di decrescita, come se fosse in procinto di calmarsi e di lasciare spazio alla quiete che segue ogni tempesta. Diversamente dal sublime di Turner, in cui la natura mostra tutta la sua forza travolgente al punto di far percepire all’uomo la sua esiguità, nel caso di Vladimiro Tomasi si potrebbe parlare del pittoresco in cui viene messa in evidenza l’armonia, l’equilibrio tra tutti gli elementi che compongono la tela a parte l’uomo la cui presenza è intuibile solo dagli edifici o dalle barche in lontananza di alcuni dipinti.

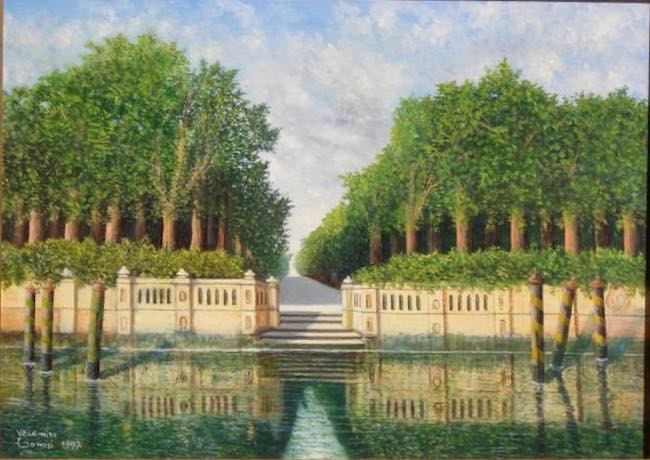

In Venezia – il Parco Francese emerge il senso della prospettiva quasi rigoroso che è una delle altre caratteristiche di Tomasi, quell’impostazione razionalista con cui l’artista guarda gli scorci di fronte a sé infondendo nel fruitore una sensazione di ordine, di perfezione estetica e di ricerca dell’ordine molto vicina al Verismo il quale tuttavia viene oltrepassato non appena lo sguardo va a posarsi sulle acque calme o sulle chiome degli alberi in cui le pennellate brevi e sottili, l’accostamento cromatico e la minuziosità della descrizione, non possono non richiamare l’Impressionismo. Dunque, malgrado la tendenza alla fedeltà descrittiva questa tela ha il potere di toccare le corde emozionali, di indurre chi guarda a desiderare di trovarsi esattamente in quel parco, respirandone l’odore della vegetazione, ascoltandone il silenzio quasi magico e senza tempo.

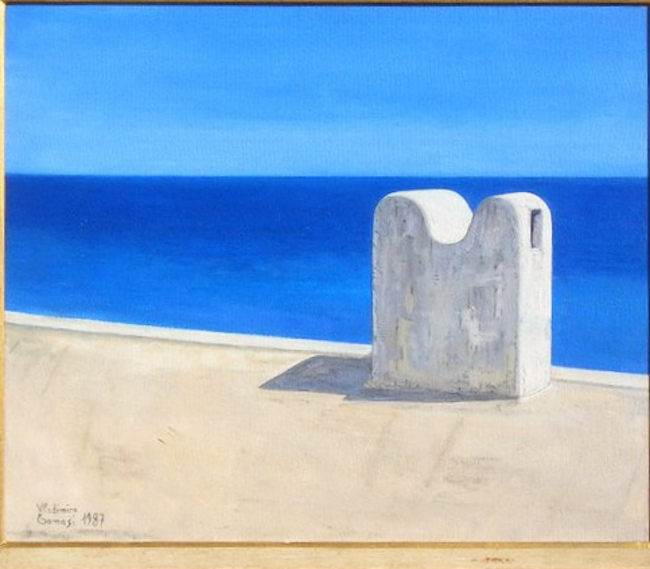

Il dipinto Estate a Stromboli invece mostra una tendenza pittorica decisamente realista, eppure nella scelta del soggetto, un semplice blocco di cemento bianco a contrasto con l’azzurro intenso del mare, sembra quasi avvicinarsi alla Metafisica, stimolando la riflessione su quanto sterminata e immensa sia la presenza della natura in tutto ciò che circonda l’essere umano e su quanto in fondo il suo apporto a quella bellezza sia trascurabile e tuttavia al tempo stesso in qualche modo interessante laddove si pone in dialogo armonico, e non invasivo, nell’ambiente che lo ospita. Il tratto pittorico qui è deciso, rigoroso, le sfumature e le ombre sono ottenute in maniera tradizionale per rendere al meglio la semplicità di un dettaglio che ha colpito l’attenzione di Vladimiro Tomasi esattamente per la stessa purezza e immediatezza riprodotta fedelmente nell’opera.

Vladimiro Tomasi ha avuto una grande carriera artistica per tutto il corso del Novecento, e anche durante il primo decennio del Ventunesimo secolo, lasciando un’importante traccia nella pittura italiana anche grazie ai numerosi collezionisti che lo hanno sostenuto apprezzando la sua purezza espressiva. L’artista è scomparso nel 2011 e ora gli eredi stanno lavorando per far riscoprire al pubblico il patrimonio artistico di Vladimiro Tomasi.

VLADIMIRO TOMASI-CONTATTI

Email: vladimirotomasi@gmail.com

Sito web: www.vladimirotomasi.com

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/tomasivladimiro

Vladimiro Tomasi’s luminous landscapes, between Impressionism and Verism to tell the poetry of reality

The way of representing everything that belongs to the natural landscape reveals the attitude of each artist, both stylistically and in terms of feeling, since the interpretation that is given to what the gaze dwells on in the act of contemplation succeeds in leaking out the approach to life, and consequently to the message that must come out of his works by reaching the observer directly. Sometimes the view submits to the most interior sensations, letting the interiority determine the final appearance of the canvas, while at other times the desire to faithfully reproduce the beauty in front of him becomes the main guideline, while at the same time telling the poetic transport that the author experiences in the act of painting. The artist I am going to tell you about today described serene, luminous landscapes full of calm and harmony with a refined and visually striking style precisely by virtue of an aesthetic but at the same time emotional point of view.

Landscape painting, considered at least until the end of the entire eighteenth century to be of second order to portraits or religious subjects commissioned by the Church, saw in the first decades of the nineteenth century a growing interest in the cultural circles that mattered, stimulated by the marvelous and evocative artworks of English Romanticism where panoramas almost devoid of the presence of man succeeded in emphasizing the prominent role that places that have always harbored life should also have by virtue of the disruptive force or balance that can survive over the centuries. William Turner‘s sublime and John Constable‘s picturesque reproduction of the delicate British countryside paved the way for the spread of the landscape genre as a choice for many creatives who preferred to observe what was going on around them rather than focus on interiors or portraits, which were certainly more coveted by committers but definitely more visually limiting. The initial intuition of the Romantics continued especially in Italy with the School of Posillipo and the Tuscan Macchiaioli, who focused on greater precision in the description of the places immortalized and on a full use of light, as if the latter was itself the undisputed protagonist of the scenes and panoramas on which the artistic production of the members of these two schools of painting centered. The consolidation of the importance of the representation of nature came later, towards the end of the 19th century, with the establishment of a new style in which the impression of beauty, aesthetic balance and the enchantment of light that the artist received before the landscapes he was about to reproduce was introduced, thus bringing out the need to start and finish the artwork within a few hours, before losing contact with the magic that lay before the author’s gaze.

Lack of preparatory drawing, the use of color by taking it directly from the tubes, not mixed on the palette as per tradition, and its juxtaposition on the canvas with short brush strokes to impress the retina of the observer who received the overall vision only by taking distance from the artwork, were inescapable features of Impressionism that paved the way for the concept of fragmentation of color directly on the chosen medium, later taken up and expanded, precisely from the point of view of light, by the later Divisionism. Despite the fact that the starting attitude was essentially aesthetic, in the case of both Impressionism and Divisionism it is impossible not to notice how beauty is able to move the poetic chords of interiority, the same ones that vibrate in front of the landscapes of the Emilian artist Vladimiro Tomasi, passed away in 2011, who narrated the places dearest to him from different points of view, all of them, however, marked by a calm harmony and a skillful as well as suggestive use of light, sometimes even the protagonist of his canvases, as if without it one were in front of a melody with the main note missing. In him on the one hand emerges the need to fragment color in order to use it in purity by allowing it to blend only in the gaze of the observer, thus bringing him closer to Impressionism; on the other hand, there is a tendency toward faithful reproduction of the observed that pushes him toward Verism with the approach to light that had distinguished Giovanni Segantini‘s Divisionism. But more than anything else, his canvases are permeated by Vladimiro Tomasi‘s admiration of places, of views that somehow struck his aesthetic taste to the point of moving his emotions inducing him to immortalize all the beauty in front of him through his painting, thus giving life to paintings of perfect formal balance, in which every detail, any particular, is co-starring in the final result.

The rigor in the description of the buildings, the impeccable perspective apparatus, are associated with the descriptive softness of nature, in which the stroke leaves Verism to enter a poetic Impressionism that cannot help but transport the viewer into that magical world of the artist’s visual memory. The main and most striking feature is the brightness that pervades every work by Vladimiro Tomasi, even the less sunny ones present a dominant glimmer that helps to show the positive approach to life of an author who devoted his entire existence to painting. The canvas Sea storm in Masua is emblematic of his painting style and of the importance of light because the glimmer is able to illuminate even the cloud-filled sky, almost as if the color of the water agitated by the waves were able to reflect and illuminate what is above it; the movement of the sea is evident but it does not have a threatening, stormy appearance, on the contrary, it seems to be in the decreasing phase, as if it were about to calm down and make way for the quiet that follows every storm. Unlike Turner‘s sublime, in which nature shows all its overwhelming force to the point of making man perceive its meagreness, in Vladimiro Tomasi‘s case one could speak of the picturesque in which is highlighted the harmony, the balance between all the elements that make up the canvas apart from man whose presence is only intuitable from the buildings or the boats in the distance of some paintings. In Venice – the French Park emerges the almost rigorous sense of perspective that is one of Tomasi‘s other characteristics, that rationalist approach with which the artist looks at the views in front of him instilling in the viewer a feeling of order, of aesthetic perfection and search for order very close to Verism which, however, is transcended as soon as the gaze goes to rest on the calm waters or on the foliage of the trees in which the short and subtle brushstrokes, the color combination and the minuteness of the description, cannot fail to recall Impressionism.

So, despite the tendency toward descriptive fidelity this canvas has the power to touch emotional chords, to induce the viewer to wish to be exactly in that park, breathing in the smell of the vegetation, listening to its almost magical and timeless silence. The painting Summer in Stromboli, on the other hand, shows a decidedly realist pictorial tendency, yet in the choice of subject, a simple block of white concrete contrasting with the intense blue of the sea, it almost seems to approach Metaphysics, stimulating reflection on how boundless and immense is the presence of nature in all that surrounds human beings and how ultimately its contribution to that beauty is negligible and yet at the same time somehow interesting where it stands in harmonious, and non-invasive, dialogue in the environment that hosts it. The pictorial stroke here is decisive, rigorous, the shadows and nuances are obtained in a traditional way to best render the simplicity of a detail that struck Vladimiro Tomasi’s attention for exactly the same purity and immediacy faithfully reproduced in the artwork. Vladimiro Tomasi had a great artistic career throughout the course of the 20th century, and even during the first decade of the 21st century, leaving an important trace in Italian painting also thanks to the many collectors who supported him by appreciating his purity of expression. The artist passed away in 2011, and now his heirs are working to have Vladimiro Tomasi‘s artistic legacy rediscovered by the public.