Il mondo artistico degli ultimi due secoli si è avvicinato al paesaggio scoprendone la bellezza, la capacità espressiva, l’impatto emotivo che poteva avere pur costituendo una narrazione singola, pur essendo l’unico protagonista di un’opera d’arte. La rivisitazione contemporanea ha visto una personalizzazione del linguaggio pittorico sulla base della scelta stilistica di ciascun protagonista dell’arte del nostro secolo. L’artista di cui vi racconterò oggi ha un approccio minimalista e neoimpressionista contraddistinto da un forte impatto emozionale che non può non colpire l’osservatore per la sua delicatezza e anche per la sua forza.

Dopo aver vissuto un periodo d’oro intorno al primo ventennio dell’Ottocento, con il diffondersi del Romanticismo, e in particolar modo quello inglese di William Turner e di John Constable dove la forza della natura o la sua capacità di rasserenare gli animi attraverso la narrazione di luoghi familiari fu assoluta protagonista, il paesaggio tornò nell’ombra, superato dall’avvento del Realismo che diede la precedenza al ritratto o alla figura umana con tutte le sue debolezze e le lotte per l’indipendenza dal potere. Fu solo a partire dalla seconda metà dell’Ottocento, con i Macchialioli toscani prima e con l’affermarsi dell’Impressionismo poi, che la narrazione delle campagne, degli scorci marini, dei giardini borghesi, degli affascinanti specchi d’acqua lacustre, che i panorami trovarono il loro posto di tutto rispetto nell’arte, posto che continuarono ad avere malgrado le rivoluzioni pittoriche che contraddistinsero il Ventesimo secolo. Dal Divisionismo di Giovanni Segantini si passò alla completa scomposizione dell’immagine dell’Astrattismo, dove di fatto ogni contatto con la realtà osservata fu negato per affermare la superiorità dell’atto plastico sulla contingenza; malgrado questa innovazione pittorica vi furono tuttavia movimenti che vollero continuare a esprimere le loro sensazioni riproducendo i panorami che scorrevano davanti ai loro occhi, come nell’Espressionismo di Vincent Van Gogh ed Ernst Ludwig Kirchner i cui paesaggi testimoniavano la capacità di lasciar parlare l’interiorità piuttosto che limitarsi alla pura osservazione estetica. Anche il Surrealismo si legò fortemente al paesaggio per descriverlo come luogo immaginario in cui dar spazio agli incubi e alle inquietudini, come nel caso dei dipinti di Salvador Dalì, o per mantenere un contatto, in virtù delle atmosfere silenziose e immobili, con un passato classico sfuggito e il cui mistero non riusciva a essere svelato, come nella Metafisica di Giorgio de Chirico. Il Gruppo Novecento e la Scuola romana recuperarono qualche anno dopo un approccio più tradizionale ma al tempo stesso Minimalista, puntando l’obiettivo su dettagli personalizzati nei colori e nelle immagini e che divenivano il centro stesso dell’opera la quale non si manifestava più nel contesto generale ed estetico, piuttosto come riflessione e percezione interiore dell’artista che eseguiva l’opera. Nella contemporaneità il Neoimpressionismo e il Neorealismo hanno puntato l’attenzione sui paesaggi urbani, con le loro luci, con le loro strade rumorose o silenziose, come nelle visioni notturne di Jeremy Mann, e il fascino che inevitabilmente esercitano sul fruitore per la vicinanza a luoghi conosciuti e alle sensazioni da egli stesso percepite. È in un punto a metà tra Neoimpressionismo e Minimalismo che si pongono le opere dell’artista marchigiana Margherita Brunetti, di formazione autodidatta ma con un grande talento espressivo che le permette di infondere nei suoi paesaggi intrisi di atmosfera, tutta l’emozione che ha percepito quando il suo sguardo si è soffermato su di essi.

Le tonalità scelte sono tenui, delicate, come a sottolineare la sua esigenza interiore di osservare la realtà da un punto di vista positivo, aperto alla bellezza ma soprattutto alle sensazioni rigeneranti che l’approccio con la natura le infonde; scorci marini e fiori sono i suoi soggetti preferiti, quelli attraverso i quali riesce a trasmettere il percorso emozionale che la sua anima compie nel momento in cui si trova di fronte a tutto ciò che le è familiare ma anche affine alla sua delicata sensibilità. Usa la spatola Margherita Brunetti, necessaria per frammentare l’immagine in maniera differente rispetto all’Impressionismo tradizionale per la grandezza dei tocchi regolari a cui affida la composizione finale; la stesura è sottile ma al tempo stesso graffiata, quasi scolpita nella memoria emotiva, come se quell’incisione fosse necessaria a fissare sulla tela le emozioni che altrimenti fuggirebbero risultando troppo fluide, perdendosi così nel quadro generale della composizione.

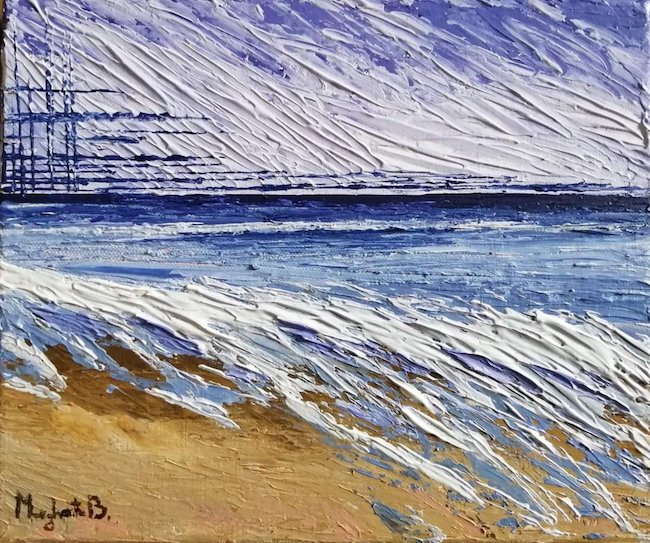

La tela Illusioni Estive è simbolica del particolare stile pittorico di Margherita Brunetti, per le spatolate brevi e rettangolari che definiscono il movimento del mare, la schiuma delle acque che si infrangono sul bagnasciuga e che si allungano sulla sabbia; l’artista riesce a infondere nell’osservatore quel senso di luminosità del sole e dell’estate, quel ricordo di momenti di vacanza che restano anche dopo essere tornati alla vita quotidiana che spesso tende a fagocitare il benessere del frangente di divertimento e di riposo.

In Dissolvenza Urbana i palazzi appaiono piccoli e lontani, come se al loro interno si perdesse l’individualità e la capacità di arrestare la corsa all’inseguimento degli impegni, di fermarsi e osservarsi mettendosi in contatto con la realtà interiore; la frammentazione del cielo, narrata con tonalità pastello in scala di rosa, è un invito da parte della Brunetti a recuperare quella connessione, a non perdere l’attitudine a dialogare con se stessi in maniera profonda e con l’altro in maniera empatica. È come se quel cielo roseo rappresentasse le mille sfaccettature, le infinite diversità dell’essere umano che spesso si nascondono dietro l’uniformità del quotidiano, dietro i pensieri e le distrazioni che impediscono di vedere i propri stessi veri colori e quelli di chi ruota intorno all’individuo.

Il dipinto Albastratta mostra tutta la necessità dell’artista di rappresentare un’immagine che poi si scolpisce nella sua anima, in quella memoria emotiva da cui non riesce a cancellarsi; è questo il motivo per cui Margherita Brunetti traccia, solca il paesaggio con incisioni emozionali, quelle linee che definiscono i punti, i dettagli che non vanno dimenticati proprio perché corrispondenti alle vibrazioni interiori del frangente in cui il suo sguardo ha fotografato il paesaggio ritratto. Il cielo e il mare fanno parte di un unico scenario in cui il sorgere del sole è protagonista, un disco rosso la cui luce evidenzia la calma dell’acqua e la leggerezza dell’aria mattutina, quella dell’inizio di un nuovo giorno pieno di speranza di serenità e di aspettativa di appagamento, quella che deriva dal saper apprezzare le piccole cose.

Sono i dipinti della serie Rose bianche a sottolineare questo concetto caro a Margherita Brunetti, quello cioè della bellezza che emerge da tutto ciò che è semplice, naturale eppure incredibilmente in grado di avvolgere lo sguardo e la sensibilità in virtù del suo essere presente intorno all’individuo senza che quest’ultimo riesca a rendersene conto; ecco perché nelle sue nature morte l’artista desidera mettere in risalto la forza emotiva che può nascere da un fiore, capace di indurre a perdersi all’interno di tutto ciò che racchiude, quel misto di regalità e di delicatezza che tanto somigliano all’anima dell’essere umano, protetta da schermi e barriere tanto quanto la rosa protegge se stessa attraverso le spine.

Le atmosfere delicate e liriche di Margherita Brunetti inducono l’osservatore a lasciarsi trasportare e conquistare dal benessere che scaturisce dalle tonalità pastello e dalle spatolate a volte più piatte altre più dense ma in entrambi i casi in grado di scomporre la realtà osservata per mostrarne la reazione alla luce, per infonderle il movimento, per indicarne le molteplici sfaccettature. Margherita Brunetti ha al suo attivo diverse mostre collettive a Mantova, Venezia e a Milano e la sua opera Dissolvenza Urbana ha ricevuto un importante premio.

MARGHERITA BRUNETTI-CONTATTI

Email: margheritabrunetti450@gmail.com

Sito web: https://www.artegante.it/margheritabrunetti

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/I-Dipinti-Di-Margherita-Brunetti-333036003871124/

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/margherita_brunetti_fine_art/

The landscapes sculpted in the soul of Neo-impressionist Minimalism by Margherita Brunetti

The artistic world of the last two centuries has approached the landscape, discovering its beauty, its expressive capacity, the emotional impact it could have even though it constitutes a single narrative, even though it is the sole protagonist of an artwork. Contemporary reinterpretation has seen a personalisation of the pictorial language on the basis of the stylistic choice of each protagonist of the art of our century. The artist I am going to tell you about today has a minimalist and neo-impressionist approach characterised by a strong emotional impact that cannot fail to strike the observer for its delicacy and also for its strength.

After experiencing a golden age around the first two decades of the 19th century, with the spread of Romanticism, especially the English Romanticism of William Turner and John Constable where the power of nature or its ability to soothe the soul through the narration of familiar places was the absolute protagonist, landscape returned to the shadows, overtaken by the advent of Realism which gave precedence to the portrait or the human figure with all its weaknesses and struggles for independence from power. It was only from the second half of the nineteenth century, first with the Tuscan Macchialioli and then with the rise of Impressionism, that the narrative of the countryside, of seascapes, of bourgeois gardens, of charming lakes, that panoramas found their respectable place in art, a place they continued to have despite the pictorial revolutions that marked the twentieth century. From Giovanni Segantini’s Divisionism to the complete decomposition of the image of Abstractionism, in which all contact with observed reality was effectively denied in order to assert the superiority of the plastic act over contingency; despite this pictorial innovation, there were nevertheless movements that wanted to continue to express their feelings by reproducing the landscapes that passed before their eyes, as in the Expressionism of Vincent Van Gogh and Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, whose landscapes testified to the ability to let the interior speak rather than limiting to pure aesthetic observation.

Surrealism, too, was strongly linked to the panoramas in order to describe it as an imaginary place in which to give space to nightmares and disquiet, as in the case of Salvador Dalì’s paintings, or to maintain contact, by virtue of the silent and immobile atmospheres, with a classical past that had escaped and whose mystery could not be revealed, as in Giorgio de Chirico’s Metaphysics. A few years later, the Novecento Group and the School of Rome recovered a more traditional but at the same time Minimalist approach, focusing on personalised details in the colours and images that became the very centre of the painting, which no longer manifested itself in the general and aesthetic context, but rather as a reflection and inner perception of the artist executing the work. In contemporary art, Neo-impressionism and Neo-realism have focused on urban landscapes, with their lights, noisy or silent streets, as in Jeremy Mann’s night visions, and the fascination they inevitably exert on the viewer due to their proximity to familiar places and the sensations they perceive. It is somewhere between Neo-Impressionism and Minimalism that the artworks of Margherita Brunetti, an artist from the Marche region of Italy, are set. Although self-taught, she has a great expressive talent that allows her to infuse her atmospheric landscapes with all the emotion she perceived when she looked at them. The tones she chooses are soft and delicate, as if to underline her inner need to observe reality from a positive point of view, open to beauty but above all to the regenerating sensations that the approach to nature instils in her; seascapes and flowers are her favourite subjects, those through which she manages to convey the emotional journey that her soul makes when it finds itself in front of everything that is familiar but also close to her delicate sensitivity. Margherita Brunetti uses the spatula, necessary to fragment the image in a different way from traditional Impressionism because of the size of the regular touches to which she entrusts the final composition; the drafting is subtle but at the same time scratched, almost sculpted in the emotional memory, as if that incision were necessary to fix on the canvas the emotions that would otherwise escape by being too fluid, thus getting lost in the general picture of the composition.

The canvas Summer Illusions is symbolic of Margherita Brunetti’s particular style of painting, with its short, rectangular brushstrokes defining the movement of the sea, the foam of the water breaking on the shoreline and stretching out on the sand. The artist succeeds in instilling in the observer that sense of the brightness of the sun and summer, that memory of holiday moments that remain even after returning to daily life, which often tends to engulf the well-being of juncture of fun and relaxation. In Urban Fading the buildings appear small and distant, as if within them one loses individuality and the ability to stop the race in pursuit of commitments, to stop and observe oneself, getting in touch with one’s inner reality; the fragmentation of the sky, narrated with pastel shades on a pink scale, is an invitation on Brunetti’s part to recover that connection, not to lose the aptitude to dialogue with oneself in a profound way and with others in an empathetic manner. It is as if that rosy sky represented the thousand facets, the infinite diversity of the human being that are often hidden behind the uniformity of everyday life, behind the thoughts and distractions that prevent from seeing our own true colours and those of the ones around us. The painting Albastratta shows all the artist’s need to represent an image that is then sculpted in her soul, in that emotional memory from which she cannot erase herself; this is the reason why Margherita Brunetti traces, furrows the landscape with emotional incisions, those lines that define the points, the details that should not be forgotten precisely because they correspond to the inner vibrations of the juncture in which her gaze has photographed the landscape portrayed. The sky and the sea are part of a single scenario in which the sunrise is the protagonist, a red disc whose light highlights the calmness of the water and the lightness of the morning air, that of the beginning of a new day full of hope of serenity and the expectation of fulfilment, that which comes from knowing how to appreciate the little things.

The paintings of the White Roses series underline this concept dear to Margherita Brunetti, that of the beauty that emerges from everything that is simple, natural and yet incredibly capable of enveloping the eye and sensitivity by virtue of its being present around the individual without that he could be able to realise it; this is why in his still lifes the artist wishes to emphasise the emotional strength that can arise from a flower, capable of inducing to lose oneself in all that it contains, that mixture of royalty and delicacy that so closely resembles the soul of the human being, protected by screens and barriers just as the rose protects itself through its thorns. Margherita Brunetti’s delicate and lyrical atmospheres induce the observer to let himself be transported and conquered by the well-being that comes from the pastel shades and the spatula strokes, sometimes flatter, sometimes denser, but in both cases able to break down the observed reality to show its reaction to light, to infuse it with movement, to indicate its many facets. Margherita Brunetti has several group exhibitions to her credit in Mantua, Venice and Milan, and her artwork Urban Fading received an important award.