La meditazione sulle tematiche esistenziali costituisce uno dei punti focali dell’arte contemporanea, un approccio fondamentale per capire, e scoprire, le riflessioni più profonde, l’invisibile che si nasconde oltre il visibile e le domande che affiorano osservando il mondo circostante e che spesso restano senza risposta. Esistono però artisti in grado di lasciar trapelare intuizioni ed emozioni sotterranee semplicemente descrivendo un paesaggio, lo scorcio di una città, che diventano altro attraverso il filtro emozionale dell’autore della tela. La protagonista di oggi svela un approccio informale eppure incredibilmente coinvolgente e in grado di far vibrare le corde emotive del fruitore.

Ai suoi esordi, intorno agli anni Quaranta del Novecento, l’Informale Materico manifestò un criterio meditato, studiato nell’affrontare il dialogo con la tela perché ciò che contava era sperimentare l’interazione dei colori con la materia, la risposta della sostanza quando sottoposta all’intervento di tonalità cromatiche che potessero darle un senso più logico e scientifico che non emozionale. Contrariamente al coevo Espressionismo Astratto, in cui le sensazioni dell’artista dovevano emergere e travolgere l’osservatore, nella corrente europea tutto doveva avere un approccio più mentale, ragionato, esplorativo dell’atto plastico. Malgrado l’intenzione di partenza tuttavia, le opere dei grandi maestri di questo movimento riuscirono a trasmettere all’osservatore la loro interiorità, le loro sensazioni, il disagio esistenziale che proprio nel periodo del secondo conflitto mondiale, e in quello immediatamente successivo, non poteva fare a meno di manifestarsi. L’intervento sulla materia trascurando la forma definita, l’introduzione di sabbia, gesso, sassi, carta di giornale, plastica, nylon, fil di ferro, contraddistinsero opere di forte impatto che giungevano in maniera aggressiva verso il fruitore, come se quelle sostanze sottolineassero, con la loro ruvidità e incisività, la difficoltà del vivere, il disagio di guardarsi dentro e accettare ferite insanabili, cercando però al contempo la terza dimensione, l’interazione con un esterno che in qualche modo avrebbe potuto alleviare il dolore delle cicatrici. Dunque in qualche modo i sacchi, le plastiche e le combustioni del maestro Alberto Burri si ricongiunsero alle tele enigmatiche e segniche di Hans Hartung, le composizioni tenui e leggere di Jean Fautrier si avvicinarono alle opere realizzate con materiali poveri di Antoni Tapìes, concludendo perciò che l’atto plastico della creazione, per quanto studiato, meditato, pensato, non poteva e non può prescindere dal comunicare le sensazioni dell’artista. Nel corso del Ventunesimo secolo tutti i confini che avevano teso a separare e differenziare le correnti creative si sono sfumati, si sono fusi ed emulsionati, proprio come i colori, dunque anche lo stile appartiene non più a un movimento bensì all’indole espressiva di ciascun artista. La dalmata Petra Forman, esponente dell’Informale Materico, mostra uno stile fortemente personale, individuale e legato al suo modo di osservare la realtà circostante in maniera aperta, empatica, e solo in un secondo momento, quando cioè si appresta a dare inizio alla fase creativa, manifesta con moderazione ed equilibrio le sensazioni assorbite in maniera quasi inconsapevole davanti ai paesaggi, agli scorci, ai frammenti di esistenza che si sono posti davanti ai suoi occhi.

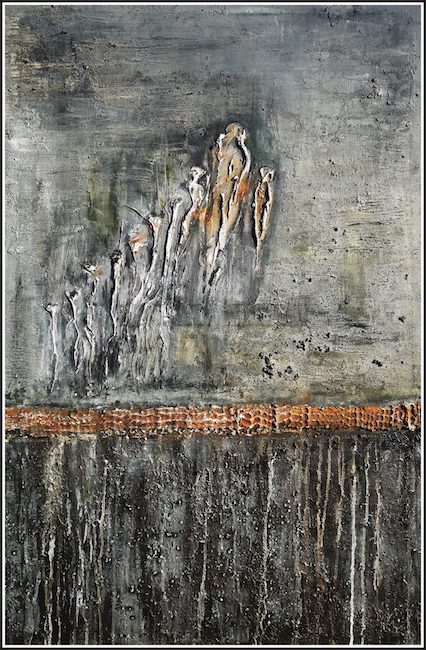

Le sue opere raccontano di panorami che hanno colpito lo sguardo della Forman e che nella loro semplicità, attraverso un fascino apparentemente invisibile, sono state in grado di far vibrare le corde interiori che si sono poi fissate nella sua memoria emotiva; il fascino del mare della Dalmazia è spesso presente nelle tele in cui sono stratificati materiali ruvidi, solidi, come ferro, farina di marmo, olio di lino, caffè, carta pigmenti, a formare quell’accumulo di sostanze che sembra metafora della vita, dei suoi percorsi, delle sovrapposizioni di esperienze e di sensazioni che ciascun evento, ciascuna circostanza portano con sé.

Il mondo emozionale di Petra Forman si esprime dunque attraverso un cammino di consapevolezza, di ascolto interiore ma anche di impulso a far vibrare le corde emotive per indurre l’osservatore a riflettere su se stesso, sulle esperienze, sui frammenti di ricordi che l’immagine narrata dall’artista porta alla luce all’interno di un eco silenzioso, di una suggestiva e avvolgente quiete.

Nel lavoro Prizba corals (Coralli di Prizba) l’artista evoca il Mar Mediterraneo con le sue acque calde e calme che non vengono raccontate attraverso una forma definita bensì in virtù del moto emozionale in cui si è perso il suo sguardo nel momento in cui l’obiettivo interiore ha scelto di immortalare quel frammento di bellezza; si ha la sensazione di sentire l’odore della salsedine, il lento muoversi delle acque, guardando la tela in cui gli alberi sono posti in fondo, quasi come se il punto di osservazione fosse quello del mare, un luogo al largo non definito da cui è possibile apprezzare il confine tra terra e acqua. L’elemento materico è limitato al tronco dell’albero, arso dal sole e piegato dal vento, che sembra volersi aggrappare al colore per sottolineare la sua presenza, il suo esistere malgrado la consapevolezza che la bellezza del mare di fronte possa metterlo in secondo piano.

Nella tela Jubilee Street Cave (La grotta del Giubileo) Petra Forman immortala un paesaggio tranquillo, ancora una volta osservato dal mare, in cui lascia emergere la magia di un luogo incantato in cui il suo sguardo si è perso, ammaliato dalla calma e dalla pace che sembra trapelare malgrado la presenza del movimento delle acque; non c’è presenza umana, forse perché abitualmente l’uomo turba l’equilibrio silenzioso di luoghi quasi mistici, o forse perché semplicemente l’artista induce l’osservatore a sentirsi egli stesso protagonista di quel frangente, a immaginarsi all’interno di quel quadro idilliaco approfittando della sensazione di pace che il panorama infonde.

Da una vaga figurazione la Forman si sposta però anche verso un distacco quasi totale dall’immagine, come nella tela Beirut in cui la parte inferiore del dipinto è rigata di nero, come se l’artista volesse mantenere memoria della guerra civile che ha attanagliato il Libano per quindici lunghi anni; la parte superiore invece rappresenta il successivo periodo di pace, di stabilità e di rigenerazione che ha permesso la rinascita di un paese e della sua gente. Il riverente silenzio che fuoriesce dalla tela è contraddistinto dalle tonalità chiare e aeree in grado di infondere nell’osservatore quel senso di compartecipazione, di solidarietà nei confronti di ciò che il popolo ha superato e la stima per essere stato in grado di rialzarsi e ricominciare.

E ancora, in Fistful of love (Pugno d’amore) l’artista sembra proporre un mondo ideale, appena intuibile in lontananza, rappresentando in maniera sfumata le nazioni che fanno parte del globo terrestre, sottolineando quanto sarebbe auspicabile trascorrere il tempo costruendo armonia e tranquillità piuttosto che pensare a come vincere le guerre; è questo il pugno di cui parla del titolo, quello della forza con la quale i potenti si oppongono gli uni agli altri dimenticando l’essenza e le esigenze del popolo, di quella comunità di persone che avrebbero solo bisogno di sentirsi bene, di non avere paura e di credere che un mondo migliore possa essere realizzabile.

Le opere di Petra Forman sono vere e proprie sovrapposizioni di colore, di materie, di sensazioni, dunque il processo creativo è lento, meditato, pur emergendo con tutto l’impatto emotivo di chi non ha bisogno di eccedere per indurre gli altri all’ascolto; il suo narrare sottovoce, pur scolpendo le sensazioni sui materiali usati, è in grado di conquistare e coinvolgere l’osservatore in maniera istintiva, emozionale. Petra Forman ha all’attivo molte mostre collettive in territorio austriaco, dove vive ormai da molti anni, e anche all’estero, tra le città più importanti Venezia, New York e Madrid.

PETRA FORMAN-CONTATTI

Email: petraforman46@gmail.com

Sito web: https://www.formanpetra.com/

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/forman.petra

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/petra_forman/

The fascination and silent magic of the indefinite in Petra Forman’s Informal Art

Meditation on existential issues is one of the focal points of contemporary art, a fundamental approach to understanding, and discovering, the deepest reflections, the invisible that hides beyond the visible and the questions that emerge when observing the world around us and that often remain unanswered. There are, however, artists who are able to reveal subterranean intuitions and emotions simply by describing a landscape, a glimpse of a city, which become something else through the emotional filter of the author of the canvas. Today’s protagonist reveals an informal yet incredibly engaging approach capable of vibrating the viewer’s emotional chords.

At its beginnings, around the 1940s, Material Informalism manifested a meditated, studied criterion in tackling the dialogue with the canvas because what mattered was experimenting the interaction of colours with matter, the response of the substance when subjected to the intervention of chromatic tones that could give it a more logical and scientific sense than an emotional one. In contrast to the Abstract Expressionism of the same period, in which the artist’s sensations had to emerge and overwhelm the observer, in the European movement everything had to have a more mental, reasoned, exploratory approach to the plastic act. Despite the initial intention, however, the artworks of the great masters of this movement succeeded in conveying to the observer their interiority, their feelings, the existential unease that could not fail to manifest itself during the Second World War and in the period immediately following it.

The intervention on the material, neglecting the defined form, the introduction of sand, plaster, stones, newspaper, plastic, nylon and wire, distinguished artworks with a strong impact that reached the viewer in an aggressive way, as if those substances underlined, with their roughness and incisiveness, the difficulty of living, the discomfort of looking inside oneself and accepting irremediable wounds, while at the same time seeking a third dimension, interaction with an outside world that could in some way alleviate the pain of the scars. Thus, in some way, the sacks, plastics and combustions of the master Alberto Burri were reunited with the enigmatic and sign-like canvases of Hans Hartung, and the soft, light compositions of Jean Fautrier came close to the works made with poor materials of Antoni Tapìes, thus concluding that the plastic act of creation, however studied, meditated and thought out, could not and cannot do without communicating the artist’s feelings.

In the course of the twenty-first century, all the boundaries that had tended to separate and differentiate creative currents have blurred, merged and emulsified, just like colours, so style no longer belongs to a movement but to the expressive nature of each artist. The Dalmatian Petra Forman, an exponent of the Material Informalism, shows a highly personal, individual style, linked to her way of observing the surrounding reality in an open, empathic way, and only later, when she is about to begin the creative phase, she manifests with moderation and balance the sensations absorbed in an almost unconscious way in front of the landscapes, the views, the fragments of existence that have been placed before her eyes. Her artworks tell of panoramas that caught Forman’s eye and that in their simplicity, through an apparently invisible charm, were able to vibrate the inner chords that were then fixed in her emotional memory; The fascination of the Dalmatian sea is often present in canvases in which rough, solid materials such as iron, marble flour, linseed oil, coffee, paper and pigments are layered, forming that accumulation of substances that seems to be a metaphor for life, its paths, the overlapping of experiences and sensations that each event, each circumstance brings with it. Petra Forman’s emotional world is thus expressed through a path of awareness, of inner listening but also of an impulse to make the emotional chords vibrate in order to induce the observer to reflect on himself, on his experiences, on the fragments of memories that the image narrated by the artist brings to light within a silent echo, of an evocative and enveloping stillness.

In the artwork Prizba corals, the artist evokes the Mediterranean Sea with its warm and calm waters which are not narrated through a defined form but rather by virtue of the emotional motion in which her gaze was lost at the moment when her inner lens chose to immortalise that fragment of beauty; one has the sensation of smelling the saltiness, the slow movement of the water, looking at the canvas where the trees are placed at the bottom, almost as if the point of observation were that of the sea, an undefined offshore place from which it is possible to appreciate the boundary between land and water. The material element is limited to the trunk of the tree, burnt by the sun and bent by the wind, which seems to want to cling to the colour to underline its presence, its existence despite the awareness that the beauty of the sea in front of it may overshadow it. In the painting Jubilee Street Cave, Petra Forman immortalises a tranquil landscape, once again observed from the sea, where she lets the magic of an enchanted place emerge in which her gaze is lost, bewitched by the calm and peace that seems to transpire despite the presence of the movement of the water; there is no human presence, perhaps because man usually disturbs the silent equilibrium of almost mystical places, or perhaps because the artist simply induces the observer to feel that he himself is the protagonist of that situation, to imagine himself inside that idyllic picture, taking advantage of the sensation of peace that the panorama instils. From a vague figuration, Forman also moves towards an almost total detachment from the image, as in the painting Beirut in which the lower part of the painting is striped black, as if the artist wished to preserve the memory of the civil war that gripped Lebanon for fifteen long years; the upper part, on the other hand, represents the subsequent period of peace, stability and regeneration that allowed the rebirth of a country and its people.

The reverent silence that emerges from the canvas is characterised by the light and airy tones that instil in the observer a sense of sharing, of solidarity with what the people have overcome and the esteem for having been able to get up and restart. And again, in Fistful of Love, the artist seems to propose an ideal world, barely perceptible in the distance, representing in a blurred way the nations that make up the globe, emphasising how desirable it would be to spend time building harmony and tranquillity rather than thinking about how to win wars; this is the fist she speaks of in the title, that of the force with which the powerful oppose one another, forgetting the essence and the needs of the people, of that community of persons who would only need to feel good, to not be afraid and to believe that a better world could be possible. Petra Forman’s artworks are true superimpositions of colour, materials and sensations, so the creative process is slow, meditated, while emerging with all the emotional impact of someone who does not need to exaggerate in order to induce others to listen; her whispered narration, while sculpting the sensations on the materials used, is able to conquer and involve the observer in an instinctive, emotional way. Petra Forman has had many group exhibitions in Austria, where she has lived for many years, and also abroad, the most important cities being Venice, New York and Madrid.