Il legame tra natura ed essere umano è una simbiosi indivisibile che però spesso nella contemporaneità viene dimenticato, quasi lasciato in disparte rispetto ad altre urgenze, a un approccio all’esistenza che sembra trascurare tutto ciò che invece oltre il visibile si nasconde. Eppure nelle epoche precedenti questa profonda connessione era stata grande protagonista dell’arte fino a trasformare addirittura gli elementi del cielo, del mare e della terra in metafora del sentire, in scrigno delle energie sottili che si nascondevano all’interno di essi e che si rivelavano attraverso lo sguardo sensibile degli artisti. Il protagonista di oggi recupera quel contatto e se ne avvale per lasciare all’osservatore una riflessione nei confronti del vivere attuale, uno stimolo ad approfondire quei simboli spesso ignorati eppure fondamentali per compiere un percorso di consapevolezza.

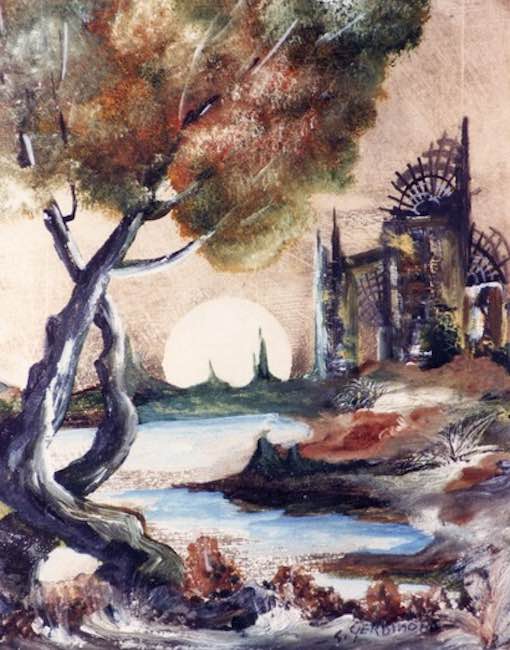

Il primo movimento pittorico orientato a considerare il paesaggio non più come mera riproduzione estetica bensì come espressione dell’interiorità dell’autore dell’opera ma anche di manifestazione della spiritualità, della forza di una natura ingestibile, imprevedibile e per questo suggestiva, fu il Romanticismo che prese piede agli inizi dell’Ottocento esattamente come rinascita rispetto al periodo dell’Illuminismo che aveva razionalizzato ogni settore dell’esistenza e del relativo Neoclassicismo artistico il quale era un pura riproduzione della realtà così come osservata. In particolar modo furono i grandi esponenti del Romanticismo inglese, come William Turner e John Constable, e di quello tedesco con Caspar David Friedrich, dalle opere dei quali emerge il senso del sublime inteso come capacità distruttiva della natura volta a sottolineare l’esiguità dell’uomo, le sensazioni emozionali suscitate dai paesaggi su cui l’occhio si sofferma e lo stimolo alla riflessione su se stessi offerto proprio dalla contemplazione dei panorami in cui spesso l’uomo è solo una piccola parte dell’immagine finale, seppure il sentire sia invece prioritario su tutti gli altri aspetti. Qualche decennio dopo, intorno agli anni Ottanta del Diciannovesimo secolo, le medesime tematiche vennero ampliate e arricchite da un nuovo approccio più spirituale, quello del Simbolismo, più orientato a prendere in considerazione l’irrazionale, l’inconoscibile, correlato al soggettivismo dell’esecutore dell’opera molto spesso attratto dal mistero e da atmosfere inquietanti e altre invece narrando quella connessione con tutto ciò che resta invisibile allo sguardo pur essendo fortemente percepibile dall’anima. Esponenti come Arnold Böcklin, che pose l’accento sul mondo ultraterreno e sulle metafore morali costituite dai miti greci e romani, Odilon Redon dove ogni paesaggio nasconde un elemento inquietante, decontestualizzato e destabilizzante di cui i protagonisti sembrano non accorgersi, e poi Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, che introdusse nelle sue tele paesaggiste le immagini del soprannaturale come angeli, spiriti e personaggi di episodi biblici. L’artista siciliano Salvatore Gerbino unisce i due generi pittorici, il Romanticismo e il Simbolismo, per dare vita a un linguaggio pittorico decisamente personale dove la natura è sfondo e al tempo stesso messaggio metaforico della condizione dell’uomo contemporaneo, spunto di riflessione su tutto ciò che nella società attuale è stato dimenticato ma che continua ad avere profonde radici da cui è impossibile prescindere.

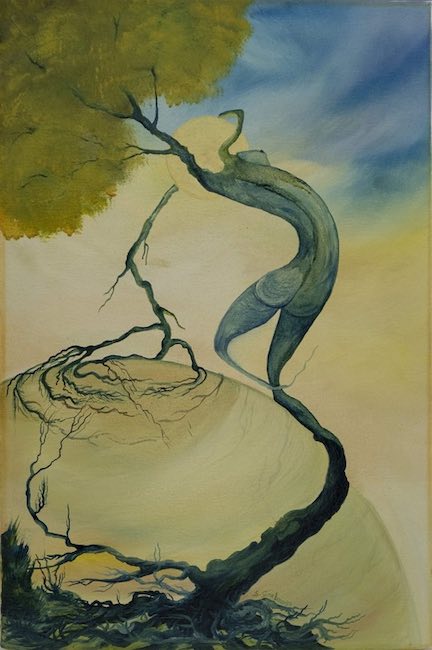

Infatti gli alberi sono protagonisti di quasi ogni sua tela, spesso spogli e apparentemente secchi eppure con la resiliente capacità di restare in piedi e resistere alle intemperie; è impossibile non percepire quei tronchi come allegoria dell’essere umano, di cui in alcuni casi assumono le sembianze avvicinando così il suo stile anche a un leggero Surrealismo che però non diviene mai predominante, che si trova a dover combattere una battaglia interiore tra la direzione verso cui il mondo sta andando e il legame con quella spiritualità e quel desiderio di restare in qualche modo legato alla sua interiorità, al suo individualismo inteso come salvezza e preservazione di tutto ciò che rende unico ciascuna persona.

Le atmosfere sono sempre irreali, decontestualizzate dalla realtà osservabile perché per Salvatore Gerbino conta molto di più portare alla luce le energie che si nascondono all’interno di un paesaggio immaginario, il quale discostandosi dall’oggettività permette all’osservatore di meditare su una difficilmente notabile essenza delle cose; ed è questo l’intento dell’artista, quello di sollecitare un approccio più introspettivo e al tempo stesso di ascolto empatico nei confronti di tutto ciò che circonda l’esistenza rendendola di fatto possibile.

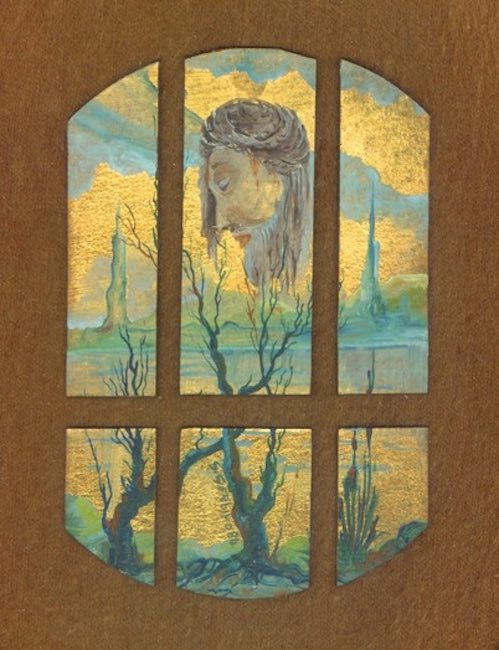

La natura dunque diviene simbolo dell’anima dell’uomo, si trasforma in voce figurativa attraverso cui portare alla luce le sottili inquietudini, l’ineluttabilità del destino umano, la sua distrazione nei confronti della sacralità e della morale a causa della quale si trova a commettere errori fatali per la sua evoluzione e per la salvezza intesa come possibilità di non perdere se stesso; Salvatore Gerbino lascia però sempre la speranza alla base delle sue tele, infatti i suoi alberi non sono mai così tanto secchi da cadere a terra, manifestano un attaccamento alle proprie radici che non riesce ad abbatterli completamente perché al di sopra di essi, nei cieli a volte più cupi e altre più sereni, c’è sempre l’energia superiore, la divinità o comunque la si voglia definire, che si pone come stimolo al miglioramento, al risveglio e all’opportunità di elevarsi.

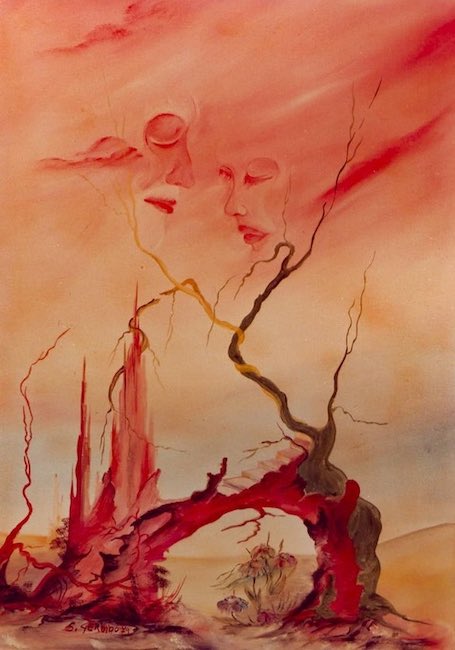

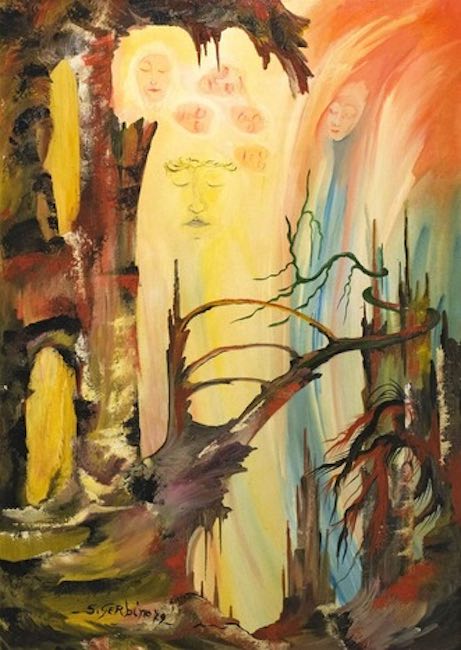

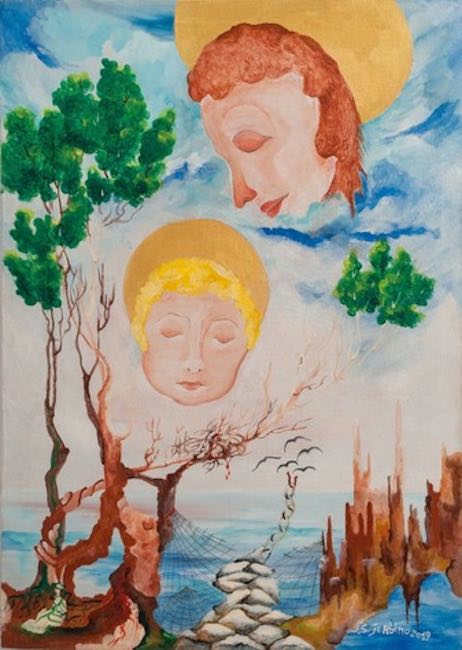

L’opera L’uomo vecchio e l’uomo nuovo rappresenta al meglio questo concetto dove i due tronchi sembrano essere la manifestazione della vita stessa, quella che appare nel cielo rosso di un tramonto che però potrebbe anche essere un’alba e che è narrata da Gerbino con i profili dei protagonisti del titolo; di fatto l’alternanza tra ciò che è stato e ciò che sarà è la base e il fine stesso della vita, quel rigenerarsi non solo dell’umanità ma anche dell’individuo quando è in grado di abbandonare il vecchio sé per aprirsi a tutto il nuovo che gli si pone davanti. Se da un lato il ciclo vitale è ineluttabile dall’altro l’artista evidenzia anche la possibilità di scelta di ciascuno, quel libero arbitrio biblico che può permettere all’uomo di sollevarsi dal suo apparente destino. Ecco perché i due tronchi sono legati, sono l’uno il divenire dell’altro, in ogni fine esiste sempre il seme di un nuovo inizio.

Nella tela Poveri cristi, allo stesso modo, le due figure stilizzate e quasi indistinguibili dai tronchi a cui sono legate, sono l’immagine dell’essere umano attuale, non quella che si vede sulla patina lucente della facciata che abitualmente viene mostrata bensì quella che si spinge oltre la superficie ed esplora le paure, il senso di inadeguatezza, le ansie e la consapevolezza dei propri errori che inevitabilmente emergono quando le persone trovano il coraggio di guardarsi allo specchio e fare un percorso introspettivo. Nel momento in cui l’uomo si assume la piena responsabilità delle proprie colpe, quelle che hanno determinato il corso della sua vita, e comprende che non è possibile continuare a perseguire la medesima strada, a quel punto l’universo si apre, lascia uno spiraglio di luce che indica la possibilità di trovare una soluzione, di dare nuova linfa a quelle interiorità messe costantemente in secondo piano rispetto alla priorità dell’apparire, imperativo della società del Ventunesimo secolo.

Altrimenti, sembra dire Salvatore Gerbino, il rischio è quello che si concretizza nella tela Ante-inquietudine d’anime in post sentenza, quel trovarsi nell’oltre, in quel troppo tardi che costringe poi l’anima, appunto, a guardarsi indietro con nostalgia o rimorso, senza poter far altro che osservare dal luogo della maggiore consapevolezza tutti gli errori che l’hanno condotta a inaridirsi, a lasciar morire ciò che di prezioso ha avuto tra le mani senza comprenderne a pieno l’importanza. Il panorama sotto lo sguardo dei volti che rappresentano lo spirito, l’essenza delle persone, è post-apocalittico, come se proprio a causa del cammino fallimentare percorso, quello che ha provocato la caduta e di conseguenza l’atteggiamento di rimorso, fossero state bruciate tutte le opportunità di porre rimedio lasciando dietro di sé aridità e desolazione.

Salvatore Gerbino ha alle sue spalle un lunghissimo percorso nel mondo dell’arte, ben cinquanta sono gli anni di attività di questo artista nato con formazione accademica ma poi in grado di crearsi una propria personale cifra stilistica che lo rende immediatamente riconoscibile; ha partecipato a numerose mostre collettive e premi d’arte, ricevendo innumerevoli premi e riconoscimenti, le sue opere sono inserite nei più importanti cataloghi italiani e la sua opera Accendi il desiderio di Preghiera è esposta in maniera permanente presso il Museo Internazionale del Crocifisso di Caltagirone, in provincia di Catania.

SALVATORE GERBINO-CONTATTI

Email: s_gerbino@virgilio.it

Sito web: https://www.salvatoregerbino.it/

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/salvatore.gerbino.77

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/sgerbino58/

Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/in/salvatore-gerbino-49528774/

The Symbolism of Salvatore Gerbino, from the silent cry of nature to a reflection on humanity

The bond between nature and the human being is an indivisible symbiosis that is, however, often forgotten in contemporary times, almost left aside in comparison to other urgencies, to an approach to existence that seems to neglect all that is hidden beyond the visible. Yet in previous epochs this profound connection had been the great protagonist of art to the point of even transforming the elements of the sky, sea and earth into a metaphor for feeling, into a treasure chest of the subtle energies hidden within them and revealed through the sensitive gaze of artists. Today’s protagonist recovers that contact and makes use of it to leave the observer with a reflection on present-day living, a stimulus to delve into those symbols that are often ignored and yet fundamental to a path of awareness.

The first pictorial movement oriented towards considering the landscape no longer as a mere aesthetic reproduction rather as an expression of the interiority of the author of the artwork, but also as a manifestation of spirituality, of the force of an unmanageable, unpredictable and therefore evocative nature, was Romanticism, which took hold at the beginning of the 19th century exactly as a rebirth compared to the period of the Enlightenment that had rationalised every sector of existence and the relative artistic Neoclassicism that was a pure reproduction of reality as observed. In particular were the great exponents of English Romanticism, such as William Turner and John Constable, and of German Romanticism with Caspar David Friedrich, from whose paintings emerges the sense of the sublime understood as nature’s destructive capacity to emphasise man’s meagreness, the emotional sensations aroused by the landscapes on which the eye lingers and the stimulus to self-reflection offered precisely by the contemplation of panoramas in which man is often only a small part of the final image, although feeling takes priority over all other aspects. A few decades later, around the 1880s, the same themes were extended and enriched by a new, more spiritual approach, that of Symbolism, more oriented towards taking into consideration the irrational, the unknowable, related to the subjectivism of the artwork’s executor very often attracted by mystery and disturbing atmospheres and others narrating that connection with everything that remains invisible to the eye despite being strongly perceptible to the soul. Exponents such as Arnold Böcklin, who emphasised the otherworldly world and the moral metaphors constituted by Greek and Roman myths, Odilon Redon where every landscape conceals a disturbing, decontextualised and destabilising element that the protagonists seem not to notice, and then Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, who introduced images of the supernatural such as angels, spirits and characters from biblical episodes into his landscape paintings. Sicilian artist Salvatore Gerbino combines the two pictorial genres, Romanticism and Symbolism, to give life to a decidedly personal pictorial language where nature is the background and at the same time a metaphorical message of the condition of contemporary man, a cue to reflect on all that has been forgotten in today’s society but continues to have deep roots from which it is impossible to disregard. In fact, trees are the protagonists of almost every one of his canvases, often bare and apparently dry yet with the resilient capacity to stand and resist the elements; it is impossible not to perceive those trunks as an allegory of the human being, whose features they sometimes take on, thus bringing his style even closer to a slight Surrealism that never becomes predominant, who finds himself having to fight an inner battle between the direction in which the world is going and the link with that spirituality and that desire to remain in some way tied to his interiority, to his individualism understood as the salvation and preservation of everything that makes each person unique.

The atmospheres are always unreal, decontextualised from observable reality, because for Salvatore Gerbino it is much more important to bring to light the energies that are hidden within an imaginary landscape, which, departing from objectivity, allows the observer to meditate on a hardly noticeable essence of things; and this is the artist’s intention, that of soliciting a more introspective approach and at the same time of empathetic listening to everything that surrounds existence, making it possible. Nature therefore becomes a symbol of man’s soul, it transforms itself into a figurative voice through which to bring to light the subtle anxieties, the inevitability of human destiny, his distraction from sacredness and morality due to which he finds himself committing errors that are fatal to his evolution and to salvation intended as the possibility of not losing himself; however Salvatore Gerbino always leaves hope at the base of his canvases, in fact his trees are never so withered to fall to the ground, they manifest an attachment to their roots that cannot completely cut them down because above them, in the sometimes darker and sometimes more serene skies, there is always the superior energy, the divinity or however one wishes to define it, which acts as a stimulus for improvement, awakening and the opportunity to rise. The painting The Old Man and the New Man best represents this concept where the two trunks seem to be the manifestation of life itself, the one which appears in the red sky of a sunset that could also be a dawn and which is narrated by Gerbino with the profiles of the protagonists of the title; in fact, the alternation between what has been and what will be is the basis and the very purpose of life, that regeneration not only of humanity but also of the individual when he is able to abandon his old self to open up to all the new that is set before him. If, on the one hand, the life cycle is inescapable, on the other, the artist also highlights the possibility of choice for each individual, that biblical free will that can allow man to rise from his apparent destiny. This is why the two trunks are linked, they are one the becoming of the other, in every end there is always the seed of a new beginning. In the painting Poor Christs, in the same way, the two stylised figures, almost indistinguishable from the trunks to which they are tied, are the image of the current human being, not the one that can be seen on the shiny veneer of the façade that is usually shown, but the one that goes beyond the surface and explores the fears, the sense of inadequacy, the anxieties and the awareness of one’s own mistakes that inevitably emerge when people find the courage to look in the mirror and take an introspective path.

The moment man takes full responsibility for his own faults, those that have determined the course of his life, and realises that it is not possible to continue pursuing the same path, at that point the universe opens up, leaves a glimmer of light that indicates the possibility of finding a solution, of giving new life to those inner selves that are constantly put in the background compared to the priority of appearance, the imperative of twenty-first century society. Otherwise, Salvatore Gerbino seems to be saying, the risk is the one that is realised in the canvas Ante-inquietude of souls in post judgement, that finding oneself in the beyond, in that too late which then forces the soul to look back with nostalgia or remorse, without being able to do anything other than observe from the place of greater awareness all the errors that have led it to wither away, to let die what was precious in its hands without fully understanding its importance. The panorama under the gaze of the faces representing the spirit, the essence of the people, is post-apocalyptic, as if precisely because of the failed path travelled, the one that caused the fall and consequently the attitude of remorse, all opportunities to remedy the situation had been burnt up, leaving behind aridity and desolation. Salvatore Gerbino has a very long career in the art world behind him, with no less than fifty years of activity by this artist, who was born with an academic education but was then able to create his own personal stylistic code that makes him immediately recognisable. He has taken part in numerous collective exhibitions and art prizes, receiving countless awards and recognitions, his artworks are included in the most important Italian catalogues and his painting Ignite the desire for Prayer is on permanent display at the Museo Internazionale del Crocifisso in Caltagirone, in the province of Catania.