Il mondo contemporaneo sembra essere costantemente una contrapposizione nei confronti di tutto ciò che si allontana dall’urgenza di ottenere obiettivi materiali, dalla tecnologia sempre più presente nella vita di ciascuno e dall’abitudine a vivere in luoghi dove si è completamente dimenticato il contatto con la natura; eppure, non molto distanti esistono realtà diverse, dove tutto ha un ritmo più lento e dove l’uomo mantiene un forte e indissolubile legame con gli animali che regnano, di fatto, in quella dimensione lontana eppure ancestrale. Alcuni creativi scelgono di mettere in evidenza la necessità dell’individuo di riconnettersi con un mondo solo apparentemente distante da sé, e soprattutto con la magia e la solennità che ne derivano contrapponendosi in qualche modo al vivere attuale dove tutti i valori della terra e della semplicità sembrano essere dimenticati, pur mostrando tuttavia la capacità di sottolineare anche il bello e l’impatto estetico che le grandi città con il loro traffico e la loro brulicante vitalità infondono. Il protagonista di oggi mostra una straordinaria capacità di restare quasi sospeso tra queste due dimensioni, svelando da un lato l’incisività dei ricordi legati al suo paese di provenienza, dall’altro la piacevolezza dell’osservare orizzonti diversi su cui si stagliano i grattacieli metropolitani.

La seconda metà del Diciannovesimo secolo ha assistito a un’evoluzione impensata dell’arte che si è rivelata essere poi anticipatrice di tutti i cambiamenti e gli sviluppi compiuti nel Novecento, quando cioè tutte le regole e gli schemi precedenti furono ripudiati per tendere verso una modernità più adeguata ai tempi; ma già verso gli anni Sessanta dell’Ottocento cominciò a formarsi un gruppo di artisti che, pur rimanendo fortemente legati all’equilibrio estetico e alla riproduzione della realtà osservata, promossero un approccio pittorico completamente innovativo che doveva adeguarsi al desiderio di raccontare immagini della vita borghese all’aria aperta, nei momenti più piacevoli e rilassati. Per fare questo scelsero di uscire dai loro studi e calarsi direttamente nelle atmosfere esterne, facendo pertanto emergere la conseguente esigenza di trovare una soluzione realizzativa più rapida della classica tavolozza dove i colori dovevano essere mescolati e sfumati; la soluzione fu quella dell’utilizzo dei nuovi colori a tubetti, di facile asciugatura, stesi sulla tela con piccole e rapide pennellate il cui impatto visivo finale era dato dall’armonia delle varie tonalità posizionate le une accanto alle altre e di cui il risultato finale era visibile solo allontanandosi dal dipinto. Claude Monet con il suo Impression au soleil levant, diede ufficialmente inizio all’Impressionismo, un movimento artistico che ebbe tra i suoi rappresentanti i maggiori maestri dell’epoca, come Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Alfred Sisley, Edgar Degas, Berthe Morisot e l’italiano Giovanni Boldini, e che segnò letteralmente l’inizio dell’epoca moderna dal punto di vista artistico. L’eredità di questi grandi interpreti fu poi raccolta e modificata dal Puntinismo, dal Post-Impressionismo e dal Divisionismo ma poi superata dal rifiuto della forma che si ebbe nei primi decenni del Novecento; troppo legato all’estetica e alla ricerca della perfezione l’Impressionismo fu considerato desueto fino alla seconda metà del Ventesimo secolo, quando cioè alcuni artisti, tra cui Leonid Afremov e poco dopo Jeremy Mann, hanno deciso di darne un’interpretazione differente, enfatizzando la scomposizione della pennellata realizzata a spatola, oppure declinandolo in visione rapita della bellezza dei paesaggi urbani, tra luci e ombre delle città.

L’artista Mande Ahmed, formatosi accademicamente in Uganda e residente a Vienna dal 2020, raccoglie l’eredità impressionista ma la riformula, ne dà una versione più fresca e originale attraverso l’uso della spatola e al contempo estremizza e quasi dissolve la definizione di ciò che i suoi occhi vedono nella quotidianità attuale o nei suoi viaggi in giro per il mondo; tuttavia l’artista non riesce a dimenticare quel mondo più selvaggio, legato alla sua Africa, che conosce tanto bene e che non può fare a meno di narrare, dividendo così la sua produzione in due serie diverse eppure incredibilmente complementari, come se queste due dimensioni tanto divergenti fossero entrambe parte della stesa realtà, quella dell’uomo che malgrado la necessità di essere razionale, efficiente, di stare al passo con i tempi, non debba mai dimenticare le proprie radici, quell’essenza primordiale di cui gli animali, nel caso di Mande Ahmed quelli della savana, sono il simbolo. Il tocco pittorico è molto frammentato, come se la spatola fosse emanazione dell’urgenza dell’artista di raccontare uno sguardo magnetico, un incedere maestoso o la curiosità che sembra coinvolgere completamente l’osservatore anche in virtù dell’assenza di contestualizzazione degli sfondi, quasi l’attenzione dovesse essere tutta focalizzata sui soggetti principali.

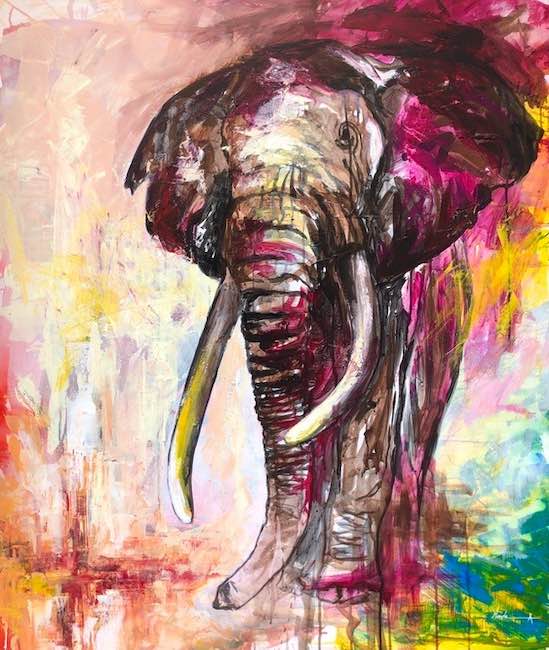

L’opera The journey home mostra l’imponenza di un gigante della savana, l’elefante, la sua lentezza e una pesantezza che di fatto sono stemperate dalle tonalità con cui Mande Ahmed avvolge l’immagine, quasi come se l’animale fosse metafora del viaggio che spesso si è chiamati a compiere, per evolvere e per accrescere la propria conoscenza, senza mai dimenticare il punto da cui si è partiti e verso cui inevitabilmente si cercherà sempre di tornare, con il corpo o con l’anima. In Quiet soul

4 Quiet soul – acrilico su tela, 40x40cm

invece racconta la calma e la regalità del re della savana, il leone, che riempie la tela con i colori che l’artista gli attribuisce, quei frammenti scomposti di sensazioni che lo contornano come se fosse attento a tutto ciò che gli accade intorno pur infondendo nell’osservatore l’impressione che sia assorto nei suoi pensieri; le spatolate sono brevi e veloci, quasi Ahmed avesse fretta di immortalare quell’istante, consapevole che nella savana un attimo dopo tutto può modificarsi e chiamare l’azione immediata. In qualche modo la consapevolezza della fugacità di ogni frangente diviene parte del patrimonio di sensazioni che appartengono all’artista e che lo hanno indotto a scegliere la tecnica impressionista applicandola anche all’altra sua serie produttiva, quella dei paesaggi urbani dove i ritmi sono persino più veloci di quelli della savana seppure meno improvvisi; il caos del rumore del traffico, dell’impellenza di correre verso qualcosa, fosse anche solo l’appartamento dove rientrare dopo una giornata di lavoro, sono perfettamente rappresentati dalla frammentazione dell’immagine, dalle pennellate indistinte che diventano più chiare solo nel momento in cui l’osservatore si allontana dalla tela, metafora di quanto in fondo all’interno di quel caleidoscopio di colori, di luci e di esistenze, quasi ci si dimentica di soffermarsi sui dettagli, sulla necessità di assaporare la bellezza intorno a sé, diversa da quella della natura eppure altrettanto coinvolgente.

Il senso di questa intenzione pittorica di Mande Ahmed emerge chiaramente dal dipinto Evening after work in cui il crepuscolo sembra accendere ancor di più la luminescenza di una città che potrebbe trovarsi in qualunque parte del mondo, con i suoi grattacieli che fanno solo da sfondo alla vita che si svolge al di sotto, sulle strade o dentro di essi, mentre attraverso lo sguardo dell’artista essi diventano protagonisti, quasi guglie protettive per tutto ciò che accade al loro interno. La sensazione che si riceve osservando quest’opera è di ammirazione nei confronti di un mondo tanto frenetico quanto però ricco di cose da fare, di interessi da coltivare, di persone da incontrare e dunque l’accezione che Ahmed dà alla vita metropolitana è positiva, ammirata, anche e soprattutto per le differenze culturali con il suo paese di provenienza dove invece a prevalere è lo stretto contatto con la natura.

Once upon a time in Vienna è invece una dedica alla città che lo ospita, a quell’atmosfera mitteleuropea che non può fare a meno di ammaliare, di conquistare con la sua eleganza qualunque viaggiatore si trovi tra le sue strade che trasudano cultura e storia; attraverso lo sguardo di Ahmed il paesaggio assume le tinte della fiaba, di un mondo incantato e magico che sembra raccontare di cavalieri, principesse, di carrozze a cavalli, di serate di gala e di mondanità dal sapore di altri tempi. Il cielo è rosso poiché probabilmente il paesaggio è stato immortalato al tramonto, ma nel contempo contribuisce a infondere all’immagine finale quell’aura fiabesca che rende il desiderio di calarsi in quelle atmosfere persino più forte. Anche in questo caso la frammentazione della pennellata, che contraddistingue lo stile di Mande Ahmed, infonde un’illusione ottica che si chiarisce solo a distanza dalla tela, anche se l’istinto è quello di avvicinarsi per scorgere dettagli che poi si perdono dentro l’interazione e la vicinanza tra le differenti tonalità.

Mande Ahmed ha esposto le sue opere in mostre collettive in Austria, Stati Uniti, Italia, Spagna, Uganda, Svezia, Kenya, Sud Africa, Paesi Bassi e Inghilterra ricevendo consensi proprio per la sua capacità di suscitare emozioni e di travolgere l’osservatore con i suoi colori.

MANDE AHMED-CONTATTI

Email: mande@mandea.art

Sito web: www.mandea.art/

Facebook: www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100066564215814

Instagram: www.instagram.com/mandea.art/

The contemporary Impressionism of Mande Ahmed, between the majesty of wild animals and the fascination of urban landscapes of the metropolis

The contemporary world seems to be in constant opposition to everything that moves away from the urgency to achieve material goals, from the technology that is increasingly present in everyone’s life, and from the habit of living in places where contact with nature has been completely forgotten; yet, not far away, there are different realities, where everything has a slower pace and where man maintains a strong and indissoluble bond with the animals that reign, in fact, in that distant yet ancestral dimension. Some creatives choose to emphasise the individual’s need to reconnect with a world only apparently distant from himself, and above all with the magic and solemnity that derive from it, contrasting in some way with present-day living where all the values of the earth and simplicity seem to be forgotten, while also showing the ability to emphasise the beauty and aesthetic impact that large cities with their traffic and teeming vitality instil. Today’s protagonist shows an extraordinary ability to remain almost suspended between these two dimensions, revealing on the one hand the incisiveness of memories linked to his country of origin, and on the other the pleasantness of observing different horizons over which metropolitan skyscrapers stand out.

The second half of the 19th century witnessed an unprecedented evolution of art that turned out to be a forerunner of all the changes and developments in the 20th century, when all previous rules and patterns were repudiated in order to strive for a modernity more in keeping with the times; but already towards the 1860s, began to form a group of artists who, while remaining strongly attached to aesthetic balance and the reproduction of observed reality, promoted a completely innovative pictorial approach that had to adapt to the desire to portray images of bourgeois life in the open air, in the most pleasant and relaxed moments. To do this they chose to leave their studios and immerse themselves directly in the outdoor atmospheres, thus giving rise to the consequent need to find a quicker solution than the classic palette where colours had to be mixed and blended; the solution was to use the new tube colours, easy to dry, spread on the canvas with small, rapid brush strokes whose final visual impact was given by the harmony of the various shades positioned next to each other and whose final result was only visible when moving away from the painting.

Claude Monet, with his Impression au soleil levant, officially initiated Impressionism, an artistic movement whose representatives included the greatest masters of the time, such as Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Alfred Sisley, Edgar Degas, Berthe Morisot and the Italian Giovanni Boldini, and which literally marked the beginning of the modern era from an artistic point of view. The legacy of these great interpreters was later picked up and modified by Pointillism, Post-Impressionism and Divisionism, but then superseded by the rejection of form in the first decades of the 20th century; too closely linked to aesthetics and the search for perfection, Impressionism was considered obsolete until the second half of the 20th century, when some artists, including Leonid Afremov and shortly afterwards Jeremy Mann, decided to give it a different interpretation, emphasising the decomposition of the brushstroke made with a palette knife, or declining it into a rapt vision of the beauty of urban landscapes, amidst the light and shadow of cities. The artist Mande Ahmed, academically trained in Uganda and resident in Vienna since 2020, takes up the Impressionist legacy but reformulates it, gives it a fresher and more original version through the use of the palette knife, and at the same time extremes and almost dissolves the definition of what his eyes see in current everyday life or in his travels around the world; he shares his production into two different yet incredibly complementary series, as if these two very divergent dimensions were both part of the same reality, that of man who, despite the need to be rational, efficient, to keep up with the times, must never forget his roots, that primordial essence of which animals, in the case of Mande Ahmed those of the savannah, are the symbol.

The pictorial touch is very fragmented, as if the palette knife were an emanation of the artist’s urgency to narrate a magnetic gaze, a majestic gait or the curiosity that seems to involve the observer completely, also by virtue of the absence of contextualisation of the backgrounds, almost as if all attention were to be focused on the main subjects. The artwork The journey home shows the impressiveness of a giant of the savannah, the elephant, its slowness and heaviness actually diluted by the tones with which Mande Ahmed envelops the image, almost as if the animal were a metaphor for the journey we are often called upon to make, to evolve and to increase our knowledge, without ever forgetting the point from which we started and towards which we will inevitably always try to return, with body or soul. In Quiet soul, on the other hand, he recounts the calm and royalty of the king of the savannah, the lion, who fills the canvas with the colours that the artist attributes to him, those decomposed fragments of sensations that surround him as if he were attentive to everything that happens around him while instilling in the observer the impression that he is absorbed in his thoughts; the strokes are short and quick, almost as if Ahmed were in a hurry to immortalise that instant, aware that in the savannah a moment later everything can change and call for immediate action. Somehow the awareness of the fleeting nature of each juncture becomes part of the heritage of sensations that belong to the artist and that led him to choose the Impressionist technique, applying it also to his other productive series, that of urban landscapes where the rhythms are even faster than those of the savannah, even if less sudden; the chaos of traffic noise, the urge to run towards something, even if only to the flat to return to after a day’s work, are perfectly represented by the fragmentation of the image, by the indistinct brushstrokes that only become clearer as the observer moves away from the canvas, a metaphor for how, deep down within that kaleidoscope of colours, lights and existences, one almost forgets to dwell on the details, on the need to savour the beauty around one, different from that of nature and yet just as captivating.

The sense of this pictorial intention of Mande Ahmed‘s emerges clearly from the painting Evening after work in which the twilight seems to light up even more the luminescence of a city that could be anywhere in the world, with its skyscrapers that only act as a backdrop to the life that takes place below, on the streets or within them, while through the artist’s gaze they become protagonists, almost protective spires for everything that happens within them. The sensation one receives when observing this artwork is of admiration for a world that is as frenetic as it is rich in things to do, interests to cultivate, and people to meet and so Ahmed‘s view of metropolitan life is therefore positive and admired, especially because of the cultural differences with his country of origin, where close contact with nature prevails. Once upon a time in Vienna is instead a dedication to the city that hosts him, to that Central European atmosphere that cannot fail to enchant, to conquer with its elegance any traveller who finds himself among its streets that exude culture and history; through Ahmed‘s gaze, the landscape takes on the hues of a fairy tale, of an enchanted and magical world that seems to tell of knights, princesses, horse-drawn carriages, gala evenings and worldliness with a flavour of times gone by. The sky is red because the landscape was probably immortalised at sunset, but at the same time it contributes to infusing the final image with that fairy-tale aura that makes the desire to immerse oneself in those atmospheres even stronger. Also in this case, the fragmentation of the brushstroke, which distinguishes Mande Ahmed‘s style, infuses an optical illusion that only becomes clear at a distance from the canvas, although the instinct is to get closer to catch a glimpse of details that are then lost in the interaction and proximity between the different tones. Mande Ahmed has exhibited his artworks in group exhibitions in Austria, the United States, Italy, Spain, Uganda, Sweden, Kenya, South Africa, the Netherlands and England, receiving acclaim for his ability to arouse emotions and overwhelm the observer with his colours.