Nell’arte contemporanea l’innovazione risiede nella capacità di un creativo di dar vita a una cifra stilistica in grado di oltrepassare e a volte fondere gli insegnamenti e le tracce lasciate da movimenti precedenti e risalenti spesso al secolo scorso, per dar vita a un tratto pittorico assolutamente personale, distintivo che possa renderlo facilmente riconoscibile fin da un primo sguardo. Malgrado la tendenza di taluni appartenenti al mondo pittorico attuale a inoltrarsi all’interno delle sensazioni più nascoste, quelle più nebulose che necessitano un atteggiamento introspettivo e orientato a osservare le ombre dei percorsi interiori, ve ne sono altri che al contrario scelgono di osservare la luce, la luminosità e la positività che può emergere solo nel momento in cui lo sguardo si sofferma su tutte quelle minuscole meraviglie che avvolgono l’esistenza. L’artista di cui vi racconterò oggi ha generato un linguaggio artistico assolutamente unico e originale, attraverso la sua capacità di lasciar fuoriuscire, e suscitare nell’osservatore, le emozioni più coinvolgenti proprio in virtù dell’approccio sorridente nei confronti della realtà che lo circonda.

Nel momento in cui l’arte si stava avviando verso la più radicale trasformazione che si concretizzò agli inizi del Novecento, vi furono delle correnti artistiche che già a partire dagli ultimi decenni del Diciannovesimo secolo cominciarono a rompere alcuni schemi fortemente legati alle regole accademiche che non erano più sufficienti agli artisti allora considerati emergenti per dar vita a opere nuove, più affini alle modificate condizioni di vita delle persone e anche al bel vivere della nuova borghesia che stava acquisendo sempre più spazio nella società. L’Impressionismo mostrò al mondo culturale dell’epoca un rivoluzionario approccio nei confronti della pittura sia dal punto di vista esecutivo poiché gli appartenenti al movimento rinunciarono completamente al disegno così come alla tecnica classica nei confronti della stesura del colore, sia dal punto di vista delle ambientazioni scelte e delle scene di vita ritratte non più legate ai ritratti di personaggi nobili o di persone del ceto sociale più basso, bensì orientate a immortalare momenti di svago e di piacevolezza nei giardini e nei parchi cittadini. Ma ciò che più determinò la reale trasformazione fu l’abitudine di dipingere en plein air, all’aperto, dunque senza la ricerca e la lentezza della pittura in studio dando dunque priorità alla velocità e all’immediatezza della realizzazione attraverso brevi pennellate da cui far emergere la luce e la fedeltà al movimento vitale dell’ambiente circostante. Le vedute e le atmosfere delicate di Claude Monet, le ballerine di Edgar Degas, i momenti di piacevolezza dei pomeriggi squisitamente francesi di Édouard Manet e di Berthe Morisot hanno reso le impressioni degli autori immortali nel tempo. D’altro canto però l’estetica e l’equilibrio formale degli impressionisti fu criticato e osteggiato da un altro gruppo pittorico altrettanto innovativo in cui invece doveva essere l’interiorità a fuoriuscire, anche a costo di allontanarsi dall’equilibrio e dall’armonia dell’immagine; l’Espressionismo infatti, questo il nome della corrente antagonista e contraria, si avvaleva di tinte irreali, forti, discostanti dalla realtà osservata purché si armonizzassero con il pulsare interiore dell’esecutore dell’opera, a volte più intenso come nei Fauves Henri Matisse e André Derain, altre più esistenzialista e cupo come nei nordeuropei Edvard Munch ed Erns Ludwig Kirchner.

L’artista abruzzese David Ariel dopo aver vissuto anni in giro per il mondo per assorbire emozioni e sensazioni da poter imprimere nella sua arte, decide di stabilirsi a Venezia per trovare la dimensione a lui più affine, quella in cui il suo canale creativo potesse realizzarsi in pieno; la possibilità di vivere nella magia della città lagunare gli ha consentito di consolidare la sua personalità artistica fino a giungere alla creazione del linguaggio attuale, un’originale mescolanza tra la frammentazione dell’immagine tipica dell’Impressionismo, il legame con la gamma cromatica più affine al mondo interiore che non alla realtà osservata appartenente alle linee guida dell’Espressionismo, e un approccio moderno, divertente, solare e a volte ironico su tutto ciò che desidera mettere in evidenza che lo avvicina alla Pop Art.

La sua tecnica prende il nome di Action Impressionist perché in realtà David Ariel entra in connessione con l’osservatore il quale diventa interprete dell’opera trasformandone il senso e il significato sulla base del proprio punto di vista, quasi come se il lavoro fosse completo solo nel momento in cui va a interagire con chi lo osserva.

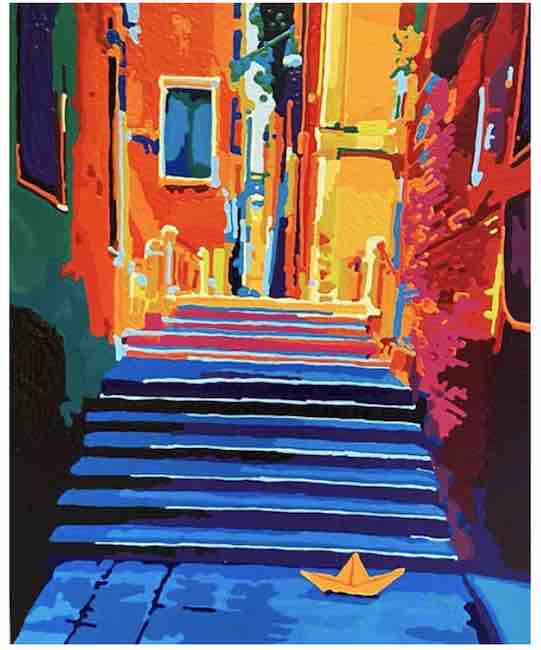

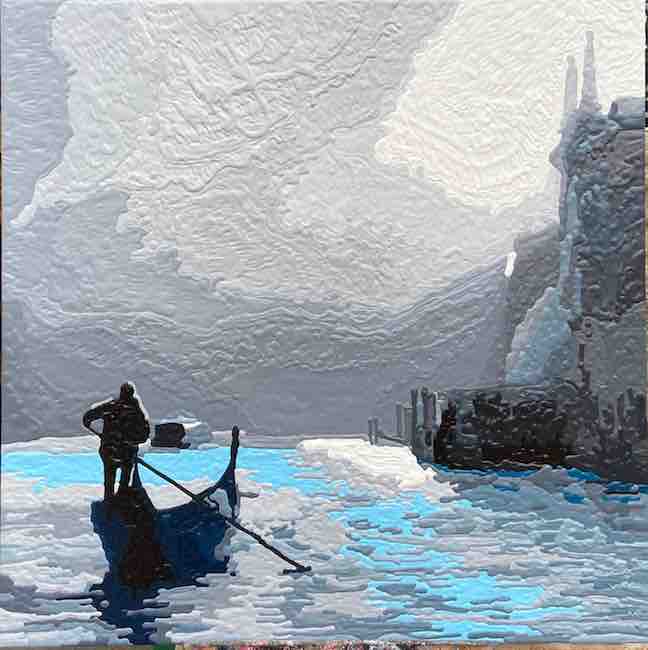

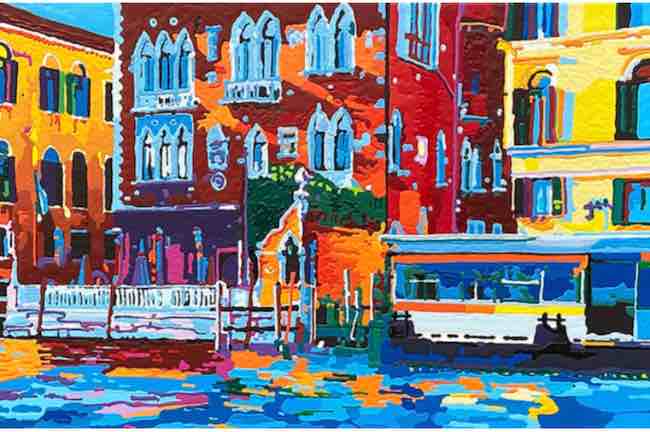

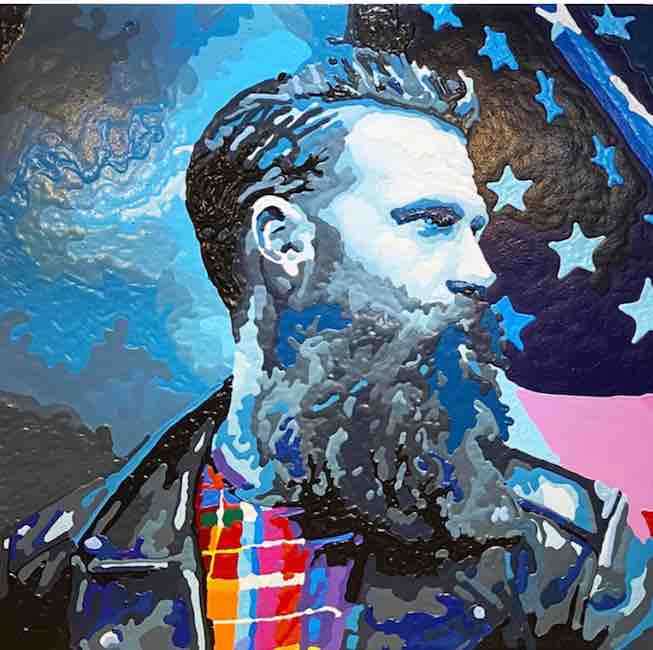

I suoi dipinti, tutti in acrilico materico su tela, coinvolgono non solo il senso della vista bensì anche quello del tatto perché il rilievo del colore utilizzato sembra richiedere il tocco per generare una connessione e un coinvolgimento maggiori trascinando letteralmente il fruitore all’interno delle scene descritte che, alla maniera impressionista, appaiono più definite da lontano e tendono invece a dissolversi in macchie colorate avvicinandosi. Ciò che resta a quel punto è il fascino e la vitalità delle tonalità Pop, le stesse che permettono all’artista di rendere iconici i soggetti da lui descritti, sia che si tratti delle calle o dei simboli di Venezia, sia che si tratti di un animale che costituisce un simbolo per lui importante, esattamente quanto iconiche erano le dive del cinema degli anni Cinquanta raccontate da Andy Warhol.

Nella tela Palazzetto Stern David Ariel immortala uno dei simboli che costantemente vede sotto i propri occhi modificandone però l’aspetto dal punto di vista cromatico perché per lui la realtà non può non essere a tinte forti, altrimenti diventerebbe ordinaria; l’individuo da solo non è in grado di cogliere le sfumature più piacevoli e divertenti di tutto ciò che passa sotto il suo sguardo pertanto il ruolo dell’artista diviene quello di interprete filtrante, o meglio di lente di ingrandimento delle emozioni spesso latenti o nascoste dietro una quotidianità che induce a prendere in considerazione la ripetitività e dunque la noia piuttosto che aprirsi alla bellezza dell’attimo presente. La vivacità dei colori rispecchia la piacevolezza di un paesaggio magico e incantato, quello di Venezia, che sembra mettersi in posa a ogni angolo per regalare ai turisti e ai visitatori un ricordo indelebile; attraverso la lente caleidoscopica di David Ariel ogni dettaglio di quello scorcio diventa più intenso e travolgente.

Nella tela Sara immortala invece un grande felino di cui viene messa in evidenza la forza ma al tempo stesso la regalità, la fierezza, pronto a scattare verso la preda o a correre verso una nuova meta; dunque i colori scelti sembrano creare la suggestione della notte intorno al suo manto, come se l’oscurità ne mettesse in evidenza la bellezza e la plasticità del corpo pronto a compiere un balzo qualora si rivelasse necessario. L’opera è dedicata alla figlia dell’artista, alla quale augura silenziosamente di avere lo stesso coraggio, la stessa indipendenza, la medesima capacità di adattarsi alle situazioni della leonessa protagonista. Anche in questo caso la matericità dei colori genera quel lieve rilievo che in qualche modo punta a interagire con l’esterno, perché in fondo l’arte è comunicazione con ciò che è intorno, con l’ambiente, con l’osservatore, con chi non può fare a meno di lasciarsi conquistare dalla narrazione unica e coinvolgente di David Ariel.

Ma la sua anima più Pop si svela nel dittico La scelta di Adam dove un Adamo caduto scopre di aver determinato il proprio destino, inconsapevole della positività o negatività della conseguenza generata eppure sicuro che la sua scelta non sia più reversibile dunque, a fronte della decisione presa, quella di effettuare la caduta commettendo il peccato originale, non può che adeguarsi alla vita in cui si trova; l’uomo dunque osserva la bandiera che sventola come se in qualche modo essa costituisse il simbolo di ciò che nel paradiso precedente ha perduto trovandosi in una dimensione differente, possibilista e libera, certo, ma forse non la migliore realtà in cui avrebbe potuto finire. Il mondo contemporaneo fatto di superficialità, di formalità e di irrequietezza, si oppone dunque alla serenità e ai valori più profondi sperimentati nella vita passata, inducendolo forse a desiderare di poter tornare indietro pur nella consapevolezza di non poterlo fare. David Ariel vive e lavora a Venezia, dove ha un suo studio visitato quotidianamente da molti turisti attratti e conquistati dall’energia dei colori delle sue opere e vanta collezionisti in tutto il mondo.

DAVID ARIEL-CONTATTI

Email: gallerialevantina@icloud.com

Sito web: https://www.levantinafactory.com/

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/davide.deguglielmi.16

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/galleria_levantina/

Impressionism Pop-colored and vital, engaging emotions in the artworks by David Ariel

In contemporary art, innovation lies in the ability of a creative artist to create a stylistic signature that goes beyond and sometimes merges the teachings and traces left by previous movements, often dating back to the last century, to create an absolutely personal, distinctive pictorial trait that can make it easily recognisable at first glance. In spite of the tendency of some in today’s pictorial world to delve into the most hidden sensations, the most nebulous ones that require an introspective attitude and oriented towards observing the shadows of inner paths, there are others who, on the contrary, choose to observe the light, the luminosity and the positivity that can only emerge when the gaze lingers on all those tiny wonders that envelop existence. The artist I am going to tell you about today has generated an absolutely unique and original artistic language, through his ability to let out, and arouse in the observer, the most engaging emotions precisely by virtue of his smiling approach to the reality that surrounds him.

At a time when art was heading towards the most radical transformation that took place at the beginning of the 20th century, there were artistic currents that, already in the last decades of the 19th century, began to break certain patterns strongly linked to academic rules that were no longer sufficient for the artists then considered emerging to create new works, more akin to the changed living conditions of people and also to the good living of the new bourgeoisie that was gaining more and more space in society. Impressionism showed the cultural world of the time a revolutionary approach to painting, both from the point of view of execution, since the members of the movement completely renounced drawing as well as the classical technique of applying colour, and from the point of view of the settings chosen and the scenes of life portrayed, no longer linked to portraits of noble figures or people from the lower social classes, but rather oriented towards immortalising moments of leisure and pleasure in gardens and city parks. But what brought about the real transformation was the habit of painting en plein air, in the open air, therefore without the research and slowness of studio painting, giving priority to the speed and immediacy of realisation through short brush strokes from which light and fidelity to the vital movement of the surrounding environment could emerge.

The views and delicate atmospheres of Claude Monet, the ballerinas of Edgar Degas, the pleasant moments of exquisitely French afternoons of Édouard Manet and Berthe Morisot have made the authors’ impressions immortal in time. On the other hand, however, the aesthetics and formal balance of the Impressionists was criticised and opposed by another, equally innovative group of painters in which instead it was the interiority that was to come through, even at the cost of straying from the balance and harmony of the image; Expressionism, in fact, this is the name of the antagonist and opposing current, used unreal, strong colours, deviating from the observed reality as long as they harmonised with the inner pulsation of the artwork’s executor, sometimes more intense as in the Fauves Henri Matisse and Andre Derain, other times more existentialist and gloomy as in the northern Europeans Edvard Munch and Erns Ludwig Kirchner. Abruzzese artist David Ariel, after living for years around the world to absorb emotions and sensations that he could imprint in his art, decided to settle in Venice to find the dimension most akin to him, the one in which his creative channel could be fully realised; the possibility of living in the magic of the lagoon city allowed him to consolidate his artistic personality to the point of creating his current language, an original mixture of the fragmentation of the image typical of Impressionism, the link with the chromatic range more akin to the inner world than to the observed reality belonging to the guidelines of Expressionism, and a modern, amusing, sunny and sometimes ironic approach to everything he wants to highlight that brings him closer to Pop Art. His technique is called Action Impressionist because David Ariel actually connects with the observer who becomes the interpreter of the artwork, transforming its meaning and significance on the basis of his own point of view, almost as if the work were only complete when it interacts with the observer.

His paintings, all in textured acrylic on canvas, involve not only the sense of sight but also that of touch because the relief of the colour used seems to require touch to generate a greater connection and involvement, literally dragging the viewer into the scenes described which, in the Impressionist manner, appear more defined from afar and tend instead to dissolve into coloured patches as one approaches. What remains at that point is the fascination and vitality of the Pop tones, the same that allow the artist to make iconic the subjects he describes, whether it be the calle or the symbols of Venice, or an animal that is a symbol for him, just as iconic as the film divas of the 1950s depicted by Andy Warhol. In the Palazzetto Stern canvas, David Ariel immortalises one of the symbols he constantly sees before his eyes, but modifying its appearance from a chromatic point of view, because for him reality cannot but be in strong colours, otherwise it would become ordinary; the individual alone is not able to grasp the most pleasant and amusing nuances of everything that passes under his gaze, so the artist’s role becomes that of filtering interpreter, or rather of magnifying glass of the emotions that are often latent or hidden behind an everyday life that induces one to consider repetitiveness and therefore boredom rather than opening up to the beauty of the present moment. The vividness of the colours reflects the pleasantness of a magical and enchanted landscape, that of Venice, which seems to pose at every corner to give tourists and visitors an indelible memory; through David Ariel’s kaleidoscopic lens every detail of that glimpse becomes more intense and overwhelming.

On the other hand, in the canvas, Sara he immortalises a large feline whose strength is highlighted, but at the same time its royalty, its pride, ready to pounce on its prey or to run towards a new destination; thus, the colours chosen seem to create the suggestion of night around its coat, as if the darkness highlighted its beauty and the plasticity of its body ready to make a leap should it prove necessary. The painting is dedicated to the artist’s daughter, to whom he silently wishes to have the same courage, the same independence, the same ability to adapt to situations as the protagonist lioness. In this case too, the materiality of the colours generates that slight relief that somehow aims at interacting with the outside world, because after all, art is communication with what is around, with the environment, with the observer, with those who cannot help but be captivated by David Ariel’s unique and engaging narrative. But its most Pop soul is revealed in the diptych The Choice of Adam where a fallen Adam discovers that he has determined his own destiny, unaware of the positivity or negativity of the consequence generated and yet certain that his choice is no longer reversible therefore, faced with the decision he has made, that of making the fall by committing original sin, he cannot but adapt to the life he finds himself in; man therefore observes the flag that flies as if in some way it constitutes the symbol of what he lost in the previous paradise, finding himself in a different dimension, possibilistic and free, certainly, but perhaps not the best reality in which he could have ended up. The contemporary world made up of superficiality, formality and restlessness is therefore opposed to the serenity and deeper values experienced in his past life, perhaps leading him to wish he could go back even though he knows he cannot. David Ariel lives and works in Venice, where he has his own studio visited daily by many tourists attracted and won over by the energy of the colours of his paintings, and boasts collectors all over the world.