La tendenza all’evasione dalla realtà, l’esigenza di rifugiarsi in mondi immaginari o in rappresentazioni fantasiose di paesaggi osservati nella realtà, appartiene da sempre all’animo sensibile degli artisti, anche in quelle fasi della storia dell’arte in cui a predominare doveva essere l’attinenza totale a tutto ciò che fosse visibile con gli occhi. Il mondo del sogno, della dimensione fiabesca o irreale diviene così anche nei tempi contemporanei, il mezzo per lasciar fluire sulla tela quelle sensazioni che solo attraverso l’elevazione dalla contingenza e la fuga verso luoghi fantastici possono manifestarsi liberamente svelando la natura dell’autore dell’opera. L’artista di cui vi racconterò oggi, pur scegliendo uno stile decisamente informale, riesce a infondere nell’osservatore la sensazione di essere trasportato nelle atmosfere magiche evocate nei titoli e poi tradotte in emozioni attraverso i colori.

Malgrado la predominanza di una descrizione fedele dei dettagli della realtà che caratterizzava l’arte del periodo pre Novecento, vi sono stati grandi rappresentanti del panorama artistico che si sono distinti per l’attitudine a evadere dalla narrazione reale dell’epoca in cui hanno operato, trasformando le loro opere in viaggi all’interno di un irreale spesso inquietante ma in ogni caso affascinante. Verso la fine del Quattrocento il pittore fiammingo Hieronymus Bosch fu inseguito e acclamato dai salotti nobili di tutta Europa in virtù dell’originalità della sua produzione e della capacità di rappresentare mondi improbabili, pieni di simboli che persino i suoi collezionisti a volte ignoravano; poco dopo, Pieter Bruegel il Vecchio raccolse l’eredità del maestro e proseguì su un cammino simile raccontando a sua volta di atmosfere surreali o mitologiche. Da quella fase in avanti, nel corso dei secoli, movimenti più strettamente legati alla realtà si alternarono a quelli più orientati a far fuoriuscire le emozioni i a raccontare di tutto l’invisibile intorno all’essere umano; il Novecento per esempio vide l’affermarsi del Simbolismo, a volte più sognante come nelle tele di Gaston Bussière, altre più inquietante come nel caso di Odilon Redon, movimento che fu di fatto precursore delle tematiche ampliate più avanti dal Surrealismo. L’inizio del Novecento ha condotto l’arte verso strade inesplorate, prima fra tutte quella della rinuncia totale della figurazione per dare la priorità alla superiorità del gesto plastico, alla pura bellezza dell’arte anche laddove fine a se stessa, senza che l’esecutore dell’opera lasciasse all’interno della tela la sua soggettività; questo passaggio fu però breve, proprio a causa della mancanza di coinvolgimento da parte dell’osservatore e anche per l’impossibilità di evoluzione da linee guida tanto rigide, come nel caso del De Stijl, pur tuttavia lasciando aperte le infinite possibilità che proprio dalla rinuncia all’osservato si erano generate. L’eredità degli interpreti dell’Astrattismo dei primi ventenni del Novecento fu così raccolta da un gruppo eterogeneo dal punto di vista stilistico ma uniforme nel sostenere il ruolo predominante che avrebbero dovuto avere le emozioni da quel momento in avanti, che prese il nome di Espressionismo Astratto; quella nuova fase diede l’opportunità agli artisti che sentivano il bisogno di esprimersi attraverso lo stile informale di arricchire di fantasia, di sensazioni e di evocazioni di luoghi silenziosi, come nel caso del Color Field di Mark Rothko, le loro tele in cui il colore divenne assoluto interprete della manifestazione espressiva. L’artista Slovacca Ingrid Mária Gábor mescola dunque la capacità immaginativa e l’attitudine a filtrare la realtà con la sua fantasia e sensibilità, alla mancanza di forma, scegliendo pertanto l’Espressionismo Astratto per raccontare il suo mondo, per descrivere quella dimensione fiabesca dentro cui ha bisogno di calarsi per riuscire a liberare un’interiorità troppo ricca per rimanere inespressa.

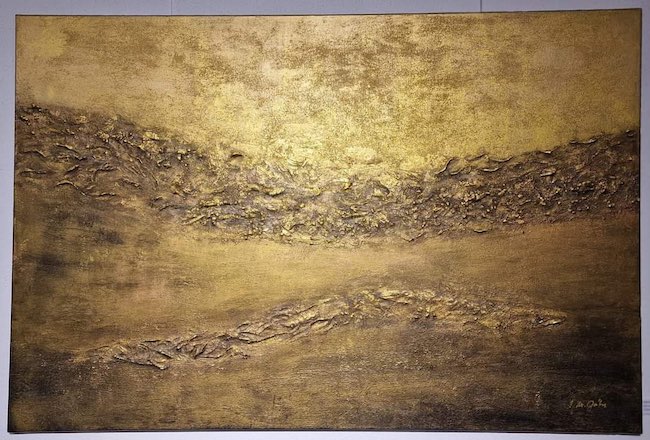

Figlia d’arte, i genitori erano nel campo del teatro, la madre attrice e il padre, Pavol Mária Gábor, scenografo di fama internazionale, viene supportata da entrambi nel perseguimento del suo sogno di essere una pittrice e così coltiva il suo talento naturale fin da bambina. La caratteristica che contraddistingue le opere di Ingrid Mária Gábor è la stratificazione del colore, quelle sovrapposizioni di tonalità, stese con l’utilizzo della spatola e della cazzuola, che sembrano completarsi reciprocamente ampliando le tonalità e l’intensità l’uno dell’altro proprio in virtù dei vari livelli che li compongono. La dimensione evocata dalle sue opere è sempre fiabesca, racconta di geishe, di principesse, di paesi esotici, che siano stati visitati oppure solo frutto della sua immaginazione non importa, ciò che conta è tutta l’emozionalità che dai colori fuoriesce interpretando il pensiero e il sentire dell’autrice e conquistando l’osservatore esattamente in virtù dell’atmosfera sognante che si sprigiona dalla tela.

La luminosità è altro elemento dominante nelle opere di Ingrid Mária Gábor perché la sua positività e il bisogno di lasciarsi andare a tutto ciò che la fantasia le suggerisce, o che la memoria ha bisogno di far fuoriuscire, la conducono verso la luce svelando così il suo approccio nei confronti della vita, morbido, delicato eppure forte e consapevole, resiliente perché non si lascia abbattere dalle ombre e dagli ostacoli bensì cerca, e di conseguenza trova, il modo per oltrepassarli, anche se questo significa a volte astrarsi dalla realtà e rifugiarsi in un ideale mondo fiabesco.

La tela Il giardino della principessa sembra essere una vera e propria evasione, il sogno di un universo costituito da bellezza, da serenità, da un tempo rallentato nei ritmi e proprio per questo in grado di essere quasi una panacea, una riappacificazione con un’interiorità che può emergere e far sentire la propria voce solo attraverso la calma di quel luogo protetto dall’esterno. Le tonalità sono intense, i fiori sono viola, gialli e blu ma lo sfondo circostante è multicolore, come se in lontananza vi fossero altre specie floreali, altri piccoli universi da scoprire avvicinandosi; i rosa e i celesti rappresentano l’interiorità, la dimensione onirica, tanto quanto i gialli e i verdi si legano alla vivacità, all’entusiasmo e alla vitalità che in quel posto incantato sembrano originarsi.

In Ballare a Rio invece Ingrid Mária Gábor racconta di tutta l’allegria e l’entusiasmo della città carioca dove il carnevale è travolgente, esaltante e in grado di conquistare grandi e piccoli per la sua festosità; in quest’opera i colori sembrano letteralmente ballare, sembrano associarsi alle note della samba che pur non potendo essere ascoltate nella realtà si concretizzano grazie alla capacità interpretativa dell’artista, grazie al suo sapiente uso della spatola attraverso cui infonde movimento agli strati in superficie generando una vera e propria danza cromatica dove ogni tonalità si mescola alle altre in un vero e proprio turbinìo.

In Geisha invece l’apparato coloristico si ridimensiona alla tricromia, come se Ingrid Mária Gábor volesse evidenziare la solennità e al contempo il mistero che da sempre avvolge la figura tradizionale giapponese, l’austerità e il contegno che contraddistinguono le ragazze accuratamente selezionate per diventare un vero e proprio simbolo della cultura del paese; il fondo nero permette alla preziosità della foglia oro e alla passionalità del rosso, che nelle geishe è costantemente presente nel trucco e negli accessori, di palpitare sulla tela con grande forza, come se l’alternanza delle due tonalità fosse necessaria a sottolineare la sontuosità dell’abbigliamento delle donne. In basso l’artista pone un richiamo ai ventagli con cui le ragazze giapponesi in abiti tradizionali coprono il volto quasi a nascondersi ma al contempo attraendo l’attenzione sullo sguardo.

In Strada spinosa il colore è neutro, completamente privo di ogni eccesso perché spesso il percorso che si va a intraprendere, pur apparendo sereno e calmo, prima o poi svela le sue difficoltà, le avversità, rappresentate nell’opera dalla riga centrale nera; eppure, esattamente come nel kintsugi giapponese in cui le fratture dei vasi vengono sigillati con l’oro, ai lati del nero Ingrid Mária Gábor appone esattamente la foglia oro per suggerire che le spine, metafora degli ostacoli, diventano un arricchimento non appena vengono superati, rafforzando l’individuo e rendendo ancor più rilevante tutto il cammino effettuato.

Ingrid Mária Gábor ha al suo attivo la partecipazione a molte mostre e premi d’arte in Slovacchia, in Italia e in Francia, dove ha ricevuto numerosi premi per il suo stile pittorico emozionale e coinvolgente e raccolto consensi sia da parte del pubblico che da parte della critica e degli addetti ai lavori.

INGRID MÁRIA GÁBOR-CONTATTI

Email: ingridmariagabor.art@gmail.com

Facebook: www.facebook.com/ingrid.cambalova

Instagram: www.instagram.com/ingridmariagaborart/

The tendency to escape from reality, the need to take refuge in imaginary worlds or in fanciful representations of landscapes observed in reality, has always belonged to the sensitive soul of artists, even in those phases of art history in which total adherence to everything visible with the eyes had to predominate. The world of the dream, of the fairytale or unreal dimension thus becomes, even in contemporary times, the means of letting those sensations flow onto the canvas that only through elevation from contingency and escape to fantastic places can freely manifest themselves, revealing the nature of the author of the artwork. The artist I am going to tell you about today, while choosing a decidedly informal style, manages to instil in the observer the sensation of being transported to the magical atmospheres evoked in the titles and then translated into emotions through the colours.

Despite the predominance of a faithful description of the details of reality that characterised the art of the pre-twentieth century period, there were great representatives of the artistic scene who distinguished themselves by their ability to escape from the real narrative of the era in which they worked, transforming their works into journeys into an often disturbing but in any case fascinating unreal. Towards the end of the 15th century, the Flemish painter Hieronymus Bosch was pursued and acclaimed by the aristocratic salons all over Europe by virtue of the originality of his production and his ability to depict improbable worlds, full of symbols that even his collectors sometimes ignored; shortly afterwards, Pieter Bruegel the Elder took up the master’s legacy and continued along a similar path, in turn narrating surreal or mythological atmospheres. From that phase onwards, over the centuries, movements more closely linked to reality alternated with those more oriented towards unleashing the emotions and recounting the invisible around human beings; the 20th century for example saw the rise of Symbolism, at times more dreamy as in the canvases of Gaston Bussière, at others more disquieting as in the case of Odilon Redon, a movement that was in fact a forerunner of the themes later expanded by Surrealism.

The beginning of the 20th century led art towards unexplored paths, first and foremost that of the total renunciation of figuration in order to give priority to the superiority of the plastic gesture, to the pure beauty of art even when it is an end in itself, without the executor of the artwork leaving his subjectivity within the canvas; this transition was short-lived, however, precisely because of the lack of involvement on the part of the observer and also because of the impossibility of evolving from such rigid guidelines, as in the case of De Stijl, while nevertheless leaving open the infinite possibilities that were generated precisely by the renunciation of the observed. The legacy of the interpreters of Abstractionism in the early twentieth century was thus taken up by a group that was heterogeneous stylistically but uniform in its support of the predominant role that emotions were to play from then on, which took the name of Abstract Expressionism; that new phase gave artists who felt the need to express themselves through the informal style the opportunity to enrich their canvases with fantasy, sensations and evocations of silent places, as in the case of Mark Rothko‘s Colour Field, in which colour became the absolute interpreter of expressive manifestation.

The Slovakian artist Ingrid Mária Gábor thus mixes the imaginative capacity and the aptitude for filtering reality with her imagination and sensitivity, with a lack of form, thus choosing Abstract Expressionism to narrate her world, to describe that fairy-tale dimension into which she needs to immerse herself in order to be able to free an interiority too rich to remain unexpressed. Daughter of art, her parents were in the theatre business, her mother an actress and her father, Pavol Mária Gábor, a set designer of international renown, she was supported by both of them in the pursuit of her dream of being a painter and thus cultivated her natural talent from an early age. The distinguishing feature of Ingrid Mária Gábor‘s artworks is the layering of colour, those superimpositions of tones, spread out with the use of spatula and trowel, that seem to complement reciprocally by amplifying each other’s tones and intensity precisely by virtue of the various layers that compose them.

The dimension evoked by her paintings is always fairytale-like, telling of geishas, princesses, exotic countries, whether they have been visited or are just a figment of her imagination does not matter, what counts is all the emotionality that comes out of the colours, interpreting the author’s thoughts and feelings and conquering the observer precisely by virtue of the dreamy atmosphere that emanates from the canvas. Luminosity is another dominant element in Ingrid Mária Gábor‘s artworks because her positivity and the need to let go of everything that her imagination suggests to her, or that her memory needs to let out, lead her towards the light, thus revealing her approach to life, soft, delicate yet strong and aware, resilient because she does not let herself be beaten down by shadows and obstacles but seeks, and consequently finds, a way to overcome them, even if this sometimes means withdrawing from reality and taking refuge in an ideal fairy-tale world. The painting The Princess’s Garden seems to be a true escape, the dream of a universe made up of beauty, of serenity, of a time slowed down in its rhythms and for this very reason able to be almost a panacea, a reconciliation with an interiority that can only emerge and make its voice heard through the calm of that place protected from the outside.

The tones are intense, the flowers are purple, yellow and blue, but the surrounding background is multicoloured, as if in the distance there were other floral species, other small universes to be discovered by getting closer; the pinks and blues represent interiority, the dreamlike dimension, just as much as the yellows and greens are linked to the vivacity, enthusiasm and vitality that seem to originate in that enchanted place. In Dancing in Rio, on the other hand, Ingrid Mária Gábor tells of all the joy and enthusiasm of the carioca city where the carnival is overwhelming, exhilarating and able to captivate young and old alike with its festivity; in this painting the colours seem to literally dance, they seem to be associated with the notes of the samba which, although they cannot be heard in reality, become concrete thanks to the artist’s interpretative ability, thanks to her skilful use of the spatula through which she infuses movement into the layers on the surface, generating a true chromatic dance where each hue mixes with the others in a veritable whirlwind.

In Geisha, on the other hand, the colour scheme is reduced to three colours, as if Ingrid Mária Gábor wanted to emphasise the solemnity and at the same time the mystery that has always enveloped the traditional Japanese figure, the austerity and demeanour that distinguish the girls carefully selected to become a true symbol of the country’s culture; the black background allows the preciousness of gold leaf and the passion of red, which is constantly present in the geishas’ make-up and accessories, to palpitate on the canvas with great force, as if the alternation of the two tones were necessary to emphasise the sumptuousness of the women’s clothing. At the bottom, the artist places a reference to the fans with which Japanese girls in traditional dress cover their faces almost as if to hide themselves but at the same time drawing attention to their gaze. In Thorny road the colour is neutral, completely devoid of any excess because often the path one is going to take, although appearing serene and calm, sooner or later reveals its difficulties, its adversities, represented in the artwork by the central black line; and yet, exactly as in Japanese kintsugi in which the fractures of the vessels are sealed with gold, on the sides of the black Ingrid Mária Gábor affixes gold leaf to suggest that the thorns, a metaphor for obstacles, become an enrichment as soon as they are overcome, strengthening the individual and making the whole path taken even more relevant. Ingrid Mária Gábor has participated in many art exhibitions and awards in Slovakia, Italy and France, where she has received numerous prizes for her emotional and engaging painting style and has been acclaimed by both the public and critics.

L'Opinionista® © since 2008 Giornale Online

Testata Reg. Trib. di Pescara n.08/08 dell'11/04/08 - Iscrizione al ROC n°17982 del 17/02/2009 - p.iva 01873660680

Pubblicità e servizi - Collaborazioni - Contatti - Redazione - Network -

Notizie del giorno -

Partners - App - RSS - Privacy - Cookie Policy

SOCIAL: Facebook - X - Instagram - LinkedIN - Youtube