In un’epoca in cui ogni cosa è sottoposta all’esame attento e acuto dell’aderenza all’esatta riproduzione della realtà con tutti i suoi punti di forza, mostrando la spasmodica ricerca di un perfezione che se non effettiva va assolutamente migliorata e abbellita fin quasi a renderla innaturale, vi sono artisti che vanno invece controcorrente e così pur mantenendo uno stile fortemente legato alla figurazione e alla fedeltà a tutto ciò che lo sguardo vede, riescono a darne una versione originale, persino nostalgica perché lasciano trasparire un romanticismo osservativo e interpretativo in cui tutto può avere un aspetto differente, più intimista, più concentrato sull’atmosfera che non sulla esatta raffigurazione di ogni sfumatura cromatica. La protagonista di oggi sceglie in modo originale di raccontare il suo punto di vista sull’umanità contemporanea, costituita da personaggi intensi e presi dai loro pensieri, attraverso l’utilizzo di una scala di grigi che non può non ricondurre alla grande fotografia d’artista del secolo scorso.

L’utilizzo della pittura in bianco e nero nel corso della storia dell’arte ha costituito una tendenza che non si è mai concretizzata, piuttosto è rimasta legata a singoli esempi sporadici il cui significato rimane a oggi un enigma; la prima opera importante in scala di grigi per cui è stata utilizzata la pittura a olio, e dunque non il tradizionale tratto del carboncino funzionale a realizzare disegni preparatori, fu Odalisque in Grisaille di Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres che sembra essere stata una copia di più piccole dimensioni, o forse uno studio per sfumature e luce della Grande odalisque. Il fascino silenzioso di questa opera minore giunge all’osservatore proprio in virtù dell’eleganza algida e al contempo morbida della bicromia. Qualche secolo dopo fu Pablo Picasso a irrompere e scuotere il mondo artistico di inizio Novecento con il suo capolavoro Guernica, in cui la mancanza del colore era simbolo dell’assenza di vita generata dalla guerra che si stava combattendo tra fratelli all’interno della Spagna. Fu però l’avvento della fotografia ad avvicinare il grande pubblico alla bellezza delle immagini in bianco e nero, che in quel caso erano però una necessità più che una scelta poiché il colore non era ancora stato introdotto, riproducendo immagini di grande impatto ma anche di grande intensità in virtù della capacità della scala di grigi di catalizzarare l’attenzione su ciò che conta, sul dettaglio che si espande fino a influenzare l’intera atmosfera circostante.

Robert Doisneau con la sua capacità di raccontare intere storie da un solo fotogramma, i frammenti di vita di Henri Cartier-Bresson, i reportage di Robert Capa, lasciarono un segno profondo nella cultura dell’epoca ma anche nell’apertura da parte degli artisti a nuove opportunità espressive. Con il sopraggiungere delle nuove correnti di avanguardia pittorica infatti, il bianco e nero fu utilizzato per introdurre l’effetto dell’illusione ottica dell’Op Art, come nelle opere di Bridget Riley, o nell’Espressionismo Astratto di Franz Kline o ancora nel Minimalismo di Ad Reinhardt; non solo, anche la magia floreale di Georgia O’Keeffe ha incontrato la suggestione del contrasto bicromo tra bianco e nero in alcune delle sue più note opere, mentre nella contemporaneità lo stesso Banksy, ritenuto il fenomeno artistico dei tempi moderni, realizza i suoi murales di denuncia della società attraverso l’utilizzo della scala di grigi. L’artista Angeles Ollarburo, di origine argentina ma ormai da molti anni residente in Italia, si ispira alla magia poetica delle immagini più iconiche dei grandi fotografi di inizio Novecento per dare vita a uno stile in cui l’Iperrealismo che emerge dalla perfezione dei dettagli raccontati, dagli sguardi, dall’atmosfera suggestiva che avvolge i suoi protagonisti, si arricchisce del fascino di una scala di grigi in cui la luce del bianco diviene rivelatoria di particolari essenziali a trasmettere la sensazione, l’emozione provata dai personaggi ritratti.

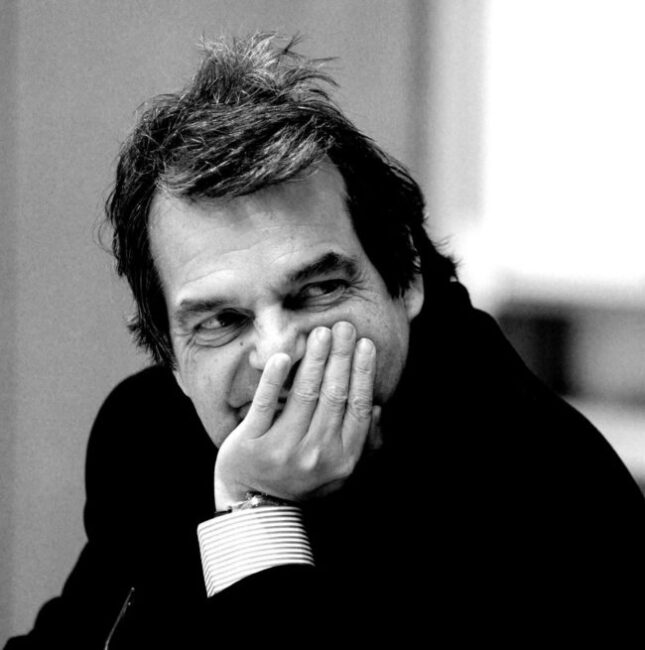

I volti sono perfettamente dettagliati, ogni espressione riesce a far percepire all’osservatore lo stato d’animo, il pensiero sotterraneo che appartiene al protagonista e che si svela attraverso la decontestualizzazione che Angeles Ollarburo dà alle sue tele, come se il nero, quasi sempre predominante, fosse un palcoscenico teatrale su cui si svolge la narrazione degli attori solisti generando un isolamento dall’ambiente circostante necessario a mettere in risalto il sentire più autentico.

Il tratto iperrealista indugia sulla resa perfetta di ogni particolare, ogni minuzioso dettaglio appartenente ai volti di bambini, alle ragazze, ai drappeggi degli abiti che si intravedono grazie alla luce apparentemente assente eppure fondamentale per sottolineare, come illuminato da un occhio di bue, tutto ciò che ha bisogno di essere colto; Angeles Ollarburo usa sapientemente il nero e il grigio, quasi alla stessa maniera in cui i maestri dell’arte dei secoli passati usavano il carboncino, eppure in lei la raffigurazione magistrale degli occhi, delle pieghe della pelle, dell’alternarsi tra luce e ombra, viene realizzata con la pittura a olio stesa in modo lineare, liscia, perfettamente sfumata ma senza alcun tipo di rilievo materico perché quella parte è affidata al disegno preparatorio che getta la base per un’impeccabilità esecutiva di cui il colore è solo funzionale all’enfatizzazione. Dunque escludendo ogni divagazione cromatica l’artista va all’essenziale, mette in evidenza uno sguardo, una posa oppure semplicemente la concentrazione di qualcuno nei confronti di ciò che si sta impegnando a fare; a volte inconsapevoli, a volte ammiccanti e altre assorti nelle loro riflessioni, i personaggi prendono vita sussurrando all’osservatore cosa sia davvero importante, quanto il resto sia superfluo per chi desidera trovare la sostanza dell’essere umano.

L’opera Soulful performance, per esempio, racconta di un frangente colto da Angeles Ollarburo durante l’ascolto di un concerto soul, quando la sua attenzione si è concentrata sull’atteggiamento del cantante completamente immerso nelle note musicali, assolutamente preso non solo dalla sua esibizione bensì anche da quel particolare stato di benessere che si sprigiona dalla sua interiorità, dal coinvolgimento totale che gli permette di fondersi con ciò che sta facendo. Qui l’artista mette in evidenza il contrasto del buio del locale con le luci soffuse che contraddistinguono i locali fumosi dove si può ascoltare quel genere di musica eppure nella tela sembra essere proprio la luce a predominare, come se la performance dell’uomo riuscisse a catturare e irradiare luminosità intorno a sé proprio per la capacità di comunicare emozione attraverso il canto.

Deep look invece rappresenta un dialogo complice tra la donna e l’osservatore, quasi lei volesse raccontare un segreto, quasi vi fosse una richiesta di attenzioni che può essere comunicata solo attraverso gli occhi; lo sguardo rappresenta pertanto una richiesta di approfondimento, di andare oltre la superficie per scoprire un mondo diverso, un universo appartenente all’altro, che sia interiore o culturale poco importa. La presenza di un chador sulla testa della ragazza sottolinea l’atmosfera intimista, segreta persino, all’interno della quale si genera quella strana e inspiegabile vicinanza nel sentire; le pieghe del velo sono perfettamente drappeggiate e in questo caso la luce emerge solo e unicamente dal volto, come se fosse esso stesso funzionale a riflettere la luminosità che catalizza l’attenzione proprio sugli occhi e sull’espressione allusiva della donna.

In Sabrina Angeles Ollarburo racconta la delicatezza di una ballerina, della sua posa delicata e leggera che sembra quasi in contrasto con la forza e la determinazione che escono dal suo sguardo, diretto in maniera sicura verso l’osservatore, perché la danza richiede autocontrollo e abnegazione completa per riuscire a eseguire passi che coinvolgono lo sforzo completo dell’intero corpo. Qui la luce è molto più presente, quasi come se la ballerina avesse appena terminato la sua esibizione e si trovasse nella posa finale e per questo ancora illuminata dall’occhio di bue che ne mette in risalto la plasticità dell’atteggiamento del corpo; il tocco iperrealista dell’artista indugia sui muscoli allungati, appena evidenti eppure presenti, sulla morbidezza delle mani, sulle scarpette da punta simbolo di leggiadria e sul tutù che però resta sullo sfondo, si confonde con lo scenario perché ciò su cui l’attenzione si concentra è la passione con cui la donna induce tutto il suo corpo a lasciarsi andare alla poesia del ballo.

Nel momento in cui Angeles Ollarburo racconta i bambini poi, la luminosità della loro innocenza si diffonde fino a pervadere l’intera tela, scacciando quasi le ombre del nero che diviene solo mezzo per enfatizzare alcuni dettagli; questa tendenza è particolarmente visibile in Sofia, dove la bambina è colta in un istante di distrazione, non guarda verso l’autrice dell’opera, sembra concentrata su qualcosa che accade al di fuori della scena e che rende il dipinto più autentico. Il bianco avvolge l’intera composizione e illumina la stanza dove la piccola protagonista si trova come se la sua spontaneità e purezza fossero capaci di diffondersi nello spazio intorno.

Angeles Ollarburo, architetto e artista con molti anni di esperienza alle spalle, prende ispirazione per le sue opere dai numerosi viaggi effettuati in Medio Oriente, Africa, America del Sud ed Europa e attualmente ha al suo attivo la partecipazione a mostre collettive in Italia e all’estero ricevendo riconoscimenti come nel caso dell’Art Box Project di Zurigo dove è stata tra le finaliste al premio.

ANGELES OLLARBURO-CONTATTI

Email: angeles.ollarburo@gmail.com

Sito web: www.saatchiart.com/en-it/account/profile/1194133

Facebook: www.facebook.com/aollarburo

Instagram: www.instagram.com/oa_is_painting/

The fascination and magic of black and white in Angeles Ollarburo’s Hyperrealism, discovering the intensity of details

At a time when everything is subjected to the careful and acute scrutiny of adherence to the exact reproduction of reality with all its strengths, showing the spasmodic search for a perfection that, if not effective, must be absolutely improved and embellished almost to the point of making it unnatural, on the other hand, there are artists who go against the current and thus, while maintaining a style strongly tied to figuration and fidelity to everything the eye sees, manage to give an original, even nostalgic version of it because they allow an observational and interpretative romanticism to shine through in which everything can have a different aspect, more intimist, more focused on the atmosphere than on the exact depiction of every chromatic nuance. Today’s protagonist chooses, in an original way, to tell her point of view on contemporary humanity, made up of intense characters caught up in their thoughts, through the use of a grey scale that cannot fail to recall the great artist photography of the last century.

The use of black and white painting throughout art history has been a trend that has never materialised, rather it has remained linked to sporadic individual examples whose significance remains an enigma to this day; the first major greyscale work for which oil paint was used, and thus not the traditional charcoal stroke used to make preparatory drawings, was Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres‘ Odalisque in Grisaille, which seems to have been a smaller copy, or perhaps a study in nuance and light of the Grande odalisque. The silent charm of this minor work comes to the viewer precisely because of the algid yet soft elegance of the two-tone painting. A few centuries later it was Pablo Picasso who broke into and shook the art world of the early 20th century with his masterpiece Guernica, in which the lack of colour symbolised the absence of life generated by the war being fought between brothers within Spain.

It was, however, the advent of photography that brought the general public closer to the beauty of black and white images, which in that case were a necessity rather than a choice since colour had not yet been introduced, reproducing images of great impact but also of great intensity by virtue of the greyscale’s ability to focus attention on what matters, on the detail that expands to influence the entire surrounding atmosphere. Robert Doisneau with his ability to tell entire stories from a single frame, Henri Cartier-Bresson‘s fragments of life, Robert Capa‘s reportages, left a profound mark on the culture of the time but also on the artists’ openness to new expressive opportunities.

With the arrival of the new avant-garde currents in painting, black and white was used to introduce the optical illusion effect of Op Art, as in the works of Bridget Riley, or in Franz Kline‘s Abstract Expressionism or Ad Reinhardt‘s Minimalism; not only that, even the floral magic of Georgia O’Keeffe has encountered the suggestion of the bichromatic contrast between black and white in some of her best-known works, while in contemporary art Banksy, considered the artistic phenomenon of modern times, creates his murals denouncing society through the use of greyscale.

The artist Angeles Ollarburo, of Argentine origin but now living in Italy for many years, is inspired by the poetic magic of the most iconic images of the great photographers of the early 20th century to give life to a style in which the Hyperrealism that emerges from the perfection of the details portrayed, from the glances, from the suggestive atmosphere that envelops hers protagonists, is enriched with the charm of a grey scale in which the light of white becomes revelatory of details that are essential to convey the sensation, the emotion felt by the characters portrayed.

The faces are perfectly detailed, each expression manages to make the observer perceive the state of mind, the subterranean thought that belongs to the protagonist and that is revealed through the decontextualisation that Angeles Ollarburo gives to her canvases, as if the black, almost always predominant, were a theatrical stage on which takes place the narrative of the solo actors, generating an isolation from the surrounding environment necessary to highlight the most authentic feeling. The hyperrealist stroke lingers on the perfect rendering of every detail, every meticulous detail belonging to children’s faces, to girls, to the draperies of dresses that can be glimpsed thanks to the apparently absent yet fundamental light that emphasises, as if illuminated by a bull’s eye, everything that needs to be captured; Angeles Ollarburo skilfully uses black and grey, almost in the same way as the masters of art of past centuries used charcoal, yet in her masterly depiction of the eyes, the folds of the skin, the alternation of light and shadow, is achieved with oil paint applied in a linear, smooth, perfectly shaded manner but without any kind of material relief because that part is entrusted to the preparatory drawing that lays the basis for an impeccable execution of which colour is only functional to emphasise.

Thus, excluding all chromatic digressions, the artist goes to the essential, highlighting a glance, a pose or simply the concentration of someone in relation to what they are undertaking to do; sometimes unconscious, sometimes winking and others absorbed in their reflections, the characters come to life whispering to the observer what is really important, how superfluous the rest is for those who wish to find the substance of the human being. The work Soulful performance, for example, recounts a moment captured by Angeles Ollarburo while listening to a soul concert, when her attention was focused on the attitude of the singer completely immersed in the musical notes, absolutely taken not only by his performance but also by that particular state of well-being that emanates from his interiority, from the total involvement that allows him to merge with what he is doing. Here the artist highlights the contrast of the darkness of the venue with the soft lights that characterise smoky places where that kind of music can be heard, and yet in the canvas it seems to be the light that predominates, as if the man’s performance manages to capture and radiate brightness around him precisely because of his ability to communicate emotion through singing. Deep look, on the other hand, represents a complicit dialogue between the woman and the observer, almost as if she wanted to tell a secret, almost as if there were a request for attention that can only be communicated through the eyes; the gaze therefore represents a request for in-depth examination, to go beyond the surface to discover a different world, a universe belonging to the other, whether it be interior or cultural, it matters little.

The presence of a chador on the girl’s head emphasises the intimist atmosphere, secret even, within which that strange and inexplicable closeness of feeling is generated; the folds of the veil are perfectly draped, and in this case the light emerges only and solely from the face, as if it were reflecting the luminosity that draws attention to the woman’s eyes and allusive expression. In Sabrina Angeles Ollarburo depicts the delicacy of a dancer, her delicate and light pose that seems almost at odds with the strength and determination that come out of her gaze, directed in a confident manner towards the viewer, because dance requires self-control and complete self-denial in order to be able to perform steps that involve the complete effort of the entire body. Here, the light is much more present, almost as if the dancer had just finished her performance and was in her final pose and therefore still illuminated by the bull’s eye that highlights the plasticity of her body posture; the artist’s hyper-realist touch lingers on the elongated muscles, barely evident yet present, on the softness of the hands, on the pointe shoes, symbol of gracefulness, and on the tutu, which, however, remains in the background, blending in with the scenery because what the attention is focused on is the passion with which the woman induces her whole body to let itself go to the poetry of the dance.

When Angeles Ollarburo tells the children, then the luminosity of their innocence spreads out until it pervades the entire canvas, almost chasing away the shadows of the black which becomes merely a means of emphasising certain details; this tendency is particularly visible in Sofia, where the little girl is caught in an instant of distraction, she is not looking towards the author of the work, she seems to be concentrating on something happening outside the scene and which makes the painting more authentic. White envelops the entire composition and illuminates the room where the little protagonist is standing, as if her spontaneity and purity were able to spread into the space around her. Angeles Ollarburo, an architect and artist with many years of experience behind her, takes inspiration for her paintings from her numerous trips to the Middle East, Africa, South America and Europe. She currently participates in group exhibitions in Italy and abroad, receiving awards such as the Art Box Project in Zurich, where she was one of the finalists for the prize.