L’arte è molto spesso testimone dei tempi, diviene filo narrativo dei periodi storici, delle sensazioni percepite e degli stati d’animo del singolo esecutore dell’opera d’arte, tuttavia in alcuni casi perde la sua funzione interiore e si sposta verso un approccio più leggero nei confronti dell’esistenza, un modo di vedere la realtà circostante attraverso un filtro ironico, sorridente, attraverso il quale potersi prendere un po’ in giro e regalare all’osservatore un punto di vista diverso su ciò che lo circonda. La protagonista di oggi è solare, ironica, in grado di vedere oltre per trovare la parte giocosa non solo dei personaggi noti, le icone del cinema e della musica, ma anche dei migliori amici dell’uomo che a volte sono coprotagonisti mentre altre invece attori principali delle sue tele.

Intorno alla metà degli anni Cinquanta del Ventesimo secolo, quando il mondo conobbe il boom economico post bellico ed emerse la nuova borghesia con un potere di acquisto crescente la quale diede di fatto inizio alla cultura del consumismo, un pioniere nell’arte di quel periodo ebbe l’intuizione di permettere alla classe media di poter acquistare e possedere un’opera pur senza dover investire i capitali del pezzo unico che non era per loro accessibile; Andy Warhol, questo il nome del genio della Pop Art, non solo comprese di dover produrre arte utilizzando un linguaggio conosciuto al popolo, attingendo perciò ai prodotti di largo consumo e ai miti del cinema, che era diventato uno dei principali appuntamenti di svago della società di quegli anni, ma anche di dover trovare un modo per rendere più abbordabile l’acquisto di tali opere. Così elaborò il concetto di serigrafia, di fatto una stampa artistica in copie numerate che avevano un costo relativamente basso e potevano dunque entrare nelle case di molte più persone dando l’opportunità di accogliere in casa la bellezza dell’arte. I grandi personaggi iconici del cinema degli anni Cinquanta come Marilyn Monroe ed Elisabeth Taylor, della musica come Mick Jagger e John Lennon, le etichette pubblicitarie più note come la zuppa Campbell e la Coca Cola, furono solo alcune delle immagini celebrate da Warhol il quale diede di fatto l’avvio a un nuovo modo di fare arte creando un movimento che intendeva andare verso il grande pubblico piuttosto che rimanere legato a un élite culturale che non costituiva più la parte essenziale della nuova società. Dunque la semplificazione del linguaggio espressivo compiuta da Roy Lichtenstein con i suoi riferimenti al mondo dei fumetti, da Steve Kaufman con i suoi supereroi, divennero un mezzo per andare verso un inedito linguaggio artistico e di un relativo collezionismo. Allo stesso modo, seppur con contenuti differenti, il Fotorealismo si imponeva di raccontare con una rappresentazione limpida, cristallina ed incredibilmente fedele alla realtà, frammenti di quotidianità, istanti di vita nelle città, come nelle opere di Richard Estes, nelle tavole calde ritratte da Ralph Goings o nei volti incredibilmente veri di Chuck Close, artisti per i quali l’attinenza all’osservato e la perfezione dell’immagine erano condizioni imprescindibili. L’artista austriaca con lontane origini spagnole Cleo Ruisz unisce i due stili pittorici dando vita a un’impronta fortemente personale e riconoscibile in cui svela il suo approccio alla vita, divertito, sorridente, pronto a far emergere il lato giocoso che costituisce in fondo il modo migliore di attraversare la quotidianità.

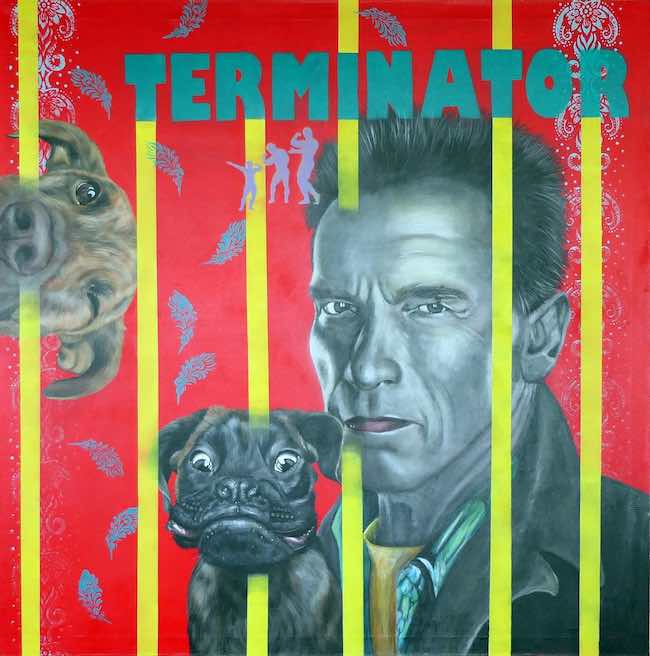

E non può fare a meno di estendere questo suo punto di vista ai personaggi che sceglie di immortalare nelle sue tele, quasi come il suo fosse un invito a prendersi meno sul serio, a coltivare l’autoironia che diviene salvezza, opportunità di osservare tutto dal di fuori e sorridere di se stessi per coltivare l’aspetto spiritoso, quello in grado di indurre a spogliarsi di quell’atteggiamento formale e ufficiale che troppo spesso diviene più una gabbia che non un comportamento legato solo alle occasioni pubbliche. Il suo stile attinge pertanto alla tendenza della Pop art di immortalare divi del cinema o protagonisti del mondo della musica, riproducendoli però con un tratto iperrealista dove la fedeltà all’immagine viene sovvertita da espressioni inaspettate nei personaggi ritratti, collocati in ambientazioni improbabili, se non impossibili che contribuiscono a sottolineare l’aspetto ironico e irriverente della pittura di Cleo Ruisz.

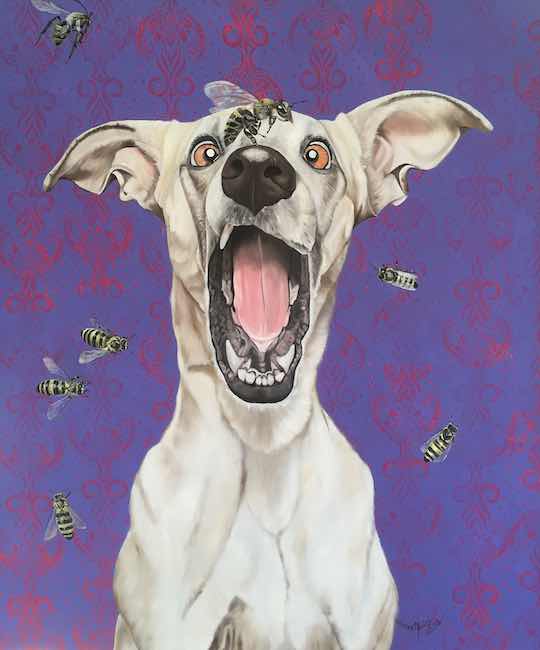

Non solo, l’artista sceglie di affiancare all’essere umano quei rappresentanti del mondo animale che colpiscono la sua attenzione e di cui coglie il lato più comico ritraendoli a volte in atteggiamenti simili a quelle del personaggio in primo piano, oppure rendendoli assoluti protagonisti di un mondo fantastico, in cui predominano l’ilarità, la felicità e la leggerezza; le espressioni degli animali, cani, pellicani, ranocchie, sono vicine a quelli dell’essere umano e la Ruisz ne riproduce la vanità, la tendenza a mettersi in mostra, a pavoneggiarsi ma poi a esplodere in sonore risate, come se in qualche modo volessero suggerire che prendendosi meno sul serio la vita è più piacevole. Gli animali sono più spontanei, meno attenti alla posa, osservano curiosamente ma anche attonitamente ciò che accade intorno a loro e l’artista ama sottolinearne e riprodurne l’aspetto buffo di alcuni comportamenti dei migliori amici dell’uomo, quando non sanno di essere visti o quando semplicemente qualcosa cattura la loro attenzione. Dunque gli umani con la loro solennità, con la loro fama, sono guardati con semplicità e immediatezza dai cani che Cleo Ruisz inserisce nelle composizioni decontestualizzate dove le righe verticali sembrano voler ingabbiare gli attori o i musicisti narrati nei loro ruoli, da cui possono uscire solo con l’autoironia, con la capacità di dimenticare cosa rappresentano ritornando semplicemente a essere.

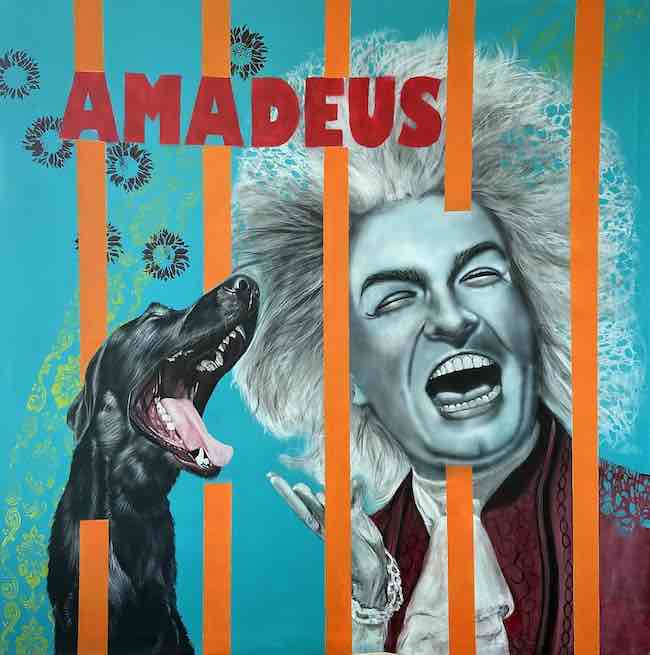

Nella tela Falco l’artista descrive un Mozart inedito, coinvolto in una risata provocata dal cane che sembra irrompere nell’opera per spezzare l’aria seriosa del grande compositore austriaco e per mostrarne il lato più ludico, umano, incapace di trattenersi vedendo e ascoltando la comica risata dell’animale. Le righe verticali sembrano indicare la convenzione dentro cui l’essere umano, più o meno famoso, cade permettendo alla strada intrapresa dal punto di vista professionale di trasformarsi in un modo di essere spesso distante dalla vera natura; lo sfondo che sembra una carta da parati infonde all’opera quella sensazione di essere sospesa nel tempo, potrebbe infatti appartenere al passato come a un impensabile presente.

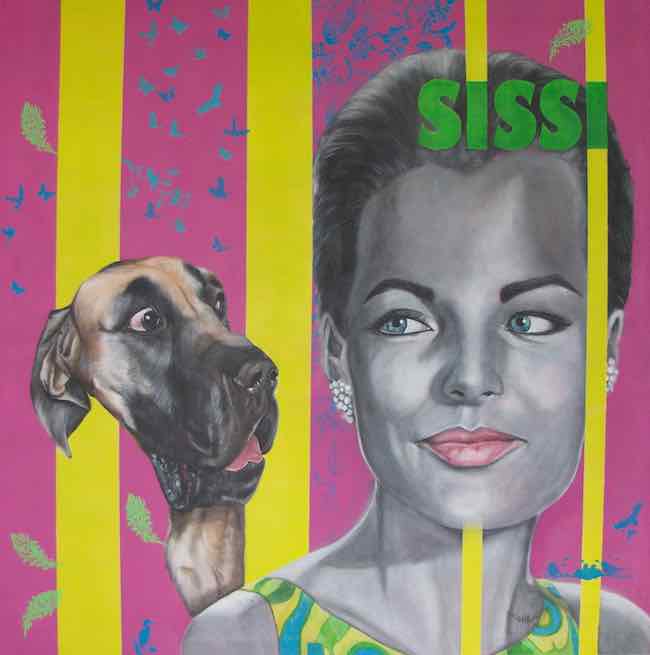

E ancora in Romy, la protagonista Romy Schneider appare curiosa nei confronti dell’alano che vede apparire con la coda dell’occhio, come se uscisse letteralmente dalla superficie della tela per scrutarla e cercare di alleviare la tristezza che l’ha accompagnata nella vita con la simpatica spontaneità che evidentemente raggiunge il suo scopo. Cleo Ruisz esalta la bellezza dell’attrice, lo sguardo limpido e il sorriso dolce e quasi timido contrapponendola allo sguardo allampanato dell’animale, stupito da tanta bellezza e ignaro della fama che la donna che sta osservando ha avuto.

La spontaneità degli animali affascina l’artista al punto di trasformarli in protagonisti assoluti di alcuni dipinti nei quali li pone in abitudini umane, come quella di fare party o di ballare il can can che però riadatta alla sua visione del mondo, quella allegra, irriverente, quasi come se la fauna che l’uomo crede di dominare si ribellasse nel modo più disarmante, deridendo tutte le vezzose abitudini, tutte le reazioni e gli atteggiamenti che all’uomo appartengono. Il mondo animale dunque si trasforma in palcoscenico sorridente e improbabile dove i pellicani convivono nello stesso ambiente con i pesci, i ranocchi, le farfalle, dove i becchi degli uccelli sono aperti in una fragorosa risata e dove tutto sembra possibile quando si sentono al sicuro dallo sguardo vigile dell’uomo.

Divertente, smitizzante, derisorio, ironico, è questo l’atteggiamento di Cleo Ruisz nei confronti della vita e dell’arte che esplora da differenti sfaccettature, infatti è anche interprete di chansons molto apprezzata dal suo pubblico, poiché in fondo la vita è un grande palcoscenico in cui ciascuno può scegliere di essere protagonista secondo le sue caratteristiche. Cleo Ruisz, che ha anche avviato una produzione di oggettistica legata alle sue opere, dalle custodie per cellulari alle borse, ha al suo attivo numerose mostre collettive in Austria e all’estero – Germania, Francia, Stati Uniti, Italia – ricevendo grandi consensi tra gli appassionati e gli addetti ai lavori.

CLEO RUISZ-CONTATTI

Email: art@cleo.at

Sito web: http://www.cleo.at/

https://www.deindesign.at/de/designs/cleo-ruisz

https://www.gabarage.at/produkt/cleo-ruisz/

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/lienhartclaudia

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/ruiszcleo_art_to_order/

The irreverent irony in the Hyperrealist Pop style of Cleo Ruisz’s fun and engaging artworks

Art is very often a witness of the times, it becomes a narrative thread of historical periods, of the perceived feelings and moods of the individual performer of the work of art, yet in some cases it loses its inner function and shifts towards a lighter approach to existence, a way of seeing the surrounding reality through an ironic, smiling filter, through which one can make fun of oneself a little and give the observer a different point of view on what surrounds him. Today’s protagonist is sunny, ironic, able to see beyond to find the playful side not only of well-known characters, the icons of cinema and music, but also of man’s best friends, who are sometimes co-protagonists while others are the main actors in her canvases.

Around the mid-1950s of the 20th century, when the world experienced the post-war economic boom and emerged the new bourgeoisie with increasing purchasing power, which effectively initiated the culture of consumerism, an art pioneer of that period had the intuition to allow the middle class to be able to buy and own a work of art without having to invest the capital of the one-off piece that was not accessible to them; Andy Warhol, this is the name of the genius of Pop Art, not only realised that he had to produce art using a language known to the people, thus drawing on consumer products and the myths of the cinema, which had become one of the main entertainment events of society in those years, but also that he had to find a way to make the purchase of such artworks more affordable. So he came up with the concept of silk-screen printing, in fact an artistic print in numbered copies that were relatively inexpensive and could therefore enter the homes of many more people, giving them the opportunity to welcome the beauty of art into their homes. The great iconic film personalities of the 1950s such as Marilyn Monroe and Elisabeth Taylor, music personalities such as Mick Jagger and John Lennon, the most famous advertising labels such as Campbell’s soup and Coca Cola, were just some of the images celebrated by Warhol who in fact initiated a new way of making art by creating a movement that intended to go towards the general public rather than remaining tied to a cultural elite that no longer constituted an essential part of the new society.

Thus, the simplification of expressive language made by Roy Lichtenstein with his references to the world of comic books, by Steve Kaufman with his superheroes, became a means of moving towards a new artistic language and a related collectionism. In the same way, albeit with different contents, Photorealism imposed itself to tell with a limpid, crystal-clear and incredibly faithful representation of reality, fragments of everyday life, instants of life in the cities, as in the paintings of Richard Estes, in the diners portrayed by Ralph Goings or in the incredibly real faces of Chuck Close, artists for whom relevance to the observed and the perfection of the image were essential conditions. The Austrian artist with distant Spanish roots, Cleo Ruisz, combines these two styles of painting to create a highly personal and recognisable imprint in which she reveals her approach to life, amused, smiling, ready to bring out the playful side that is, after all, the best way to get through everyday life. And she cannot help but extend this point of view to the characters she chooses to immortalise in her canvases, almost as if hers was an invitation to take oneself less seriously, to cultivate the self-irony that becomes salvation, an opportunity to observe everything from the outside and smile at oneself in order to cultivate the witty aspect, the one capable of inducing one to strip off that formal and official attitude that too often becomes a cage more than a behaviour linked only to public occasions.

Her style therefore draws on the Pop Art trend of immortalising film stars or protagonists from the world of music, reproducing them, however, with a hyper-realist stroke where fidelity to the image is subverted by unexpected expressions in the characters portrayed, placed in improbable, if not impossible settings that contribute to emphasising the ironic and irreverent aspect of Cleo Ruisz’s painting. Not only that, but the artist chooses to place alongside the human being those representatives of the animal world that catch her attention and whose more comical side she captures, sometimes portraying them in attitudes similar to those of the character in the foreground, or making them the absolute protagonists of a fantasy world in which hilarity, happiness and lightness predominate; the expressions of the animals – dogs, pelicans, frogs – are close to those of human beings, and Ruisz reproduces their vanity, their tendency to show off, to strut their stuff but then to burst out in loud laughter, as if to somehow suggest that by taking themselves less seriously, life is more pleasant. Animals are more spontaneous, less attentive to pose, they curiously but also attentively observe what goes on around them and the artist likes to emphasise and reproduce the funny aspect of certain behaviours of man’s best friends, when they do not know they are being seen or when something simply catches their attention. So the humans with their solemnity, with their fame, are looked at with simplicity and immediacy by the dogs that Cleo Ruisz inserts in the decontextualised compositions where the vertical lines seem to want to cage the actors or musicians narrated in their roles, from which they can only emerge with self-mockery, with the ability to forget what they represent by simply returning to being.

In the painting Falco, the artist describes an unprecedented Mozart, involved in laughter provoked by the dog that seems to burst into the work to break the great Austrian composer’s serious air and to show his more playful, human side, unable to restrain himself by seeing and hearing the animal’s comical laughter. The vertical stripes seem to indicate the convention within which the human being, more or less famous, falls, allowing the path taken professionally to turn into a way of being often distant from true nature; the wallpaper-like background infuses the artwork with that feeling of being suspended in time, it could in fact belong to the past as well as to an unthinkable present. And again in Romy, the protagonist Romy Schneider appears curious about the Great Dane that she sees appearing out of the corner of her eye, as if literally emerging from the surface of the canvas to peer at her and try to alleviate the sadness that has accompanied her through life with sympathetic spontaneity that evidently achieves its purpose. Cleo Ruisz enhances the actress’s beauty, her clear gaze and sweet, almost shy smile by contrasting it with the lanky gaze of the animal, amazed by so much beauty and unaware of the fame of the woman he is observing. The spontaneity of the animals fascinates the artist to the point of transforming them into the absolute protagonists of some paintings in which she places them in human habits, such as partying or can-can dancing, which she re-adapts to her vision of the world, the cheerful, irreverent one, almost as if the fauna that man believes he dominates were rebelling in the most disarming way, mocking all the vexatious habits, all the reactions and attitudes that belong to man.

The animal world is thus transformed into a smiling, improbable stage where pelicans coexist in the same environment with fish, frogs and butterflies, where birds’ beaks are opened in thunderous laughter and where everything seems possible when they feel safe from man’s watchful gaze. Amusing, demythologising, mocking, ironic, this is Cleo Ruisz’s attitude towards life and art that she explores from different facets. In fact, she is also a performer of chansons that are much appreciated by her audience, because after all, life is one big stage where everyone can choose to be a protagonist according to their own characteristics. Cleo Ruisz, who has also started a production of objects related to her artworks, from mobile phone cases to bags, has numerous group exhibitions to her credit in Austria and abroad – Germany, France, the United States, Italy – receiving great acclaim among enthusiasts and professionals.