Molto spesso la necessità di guardare e rielaborare il passato artistico sfocia in una presa di posizione da parte dei creativi contemporanei attraverso la quale si pongono in posizione di ammirazione, oppure di rifiuto o ancora di contestazione di tutti i punti di vista, gli approcci pittorici e la narrazione che è stata fatta della realtà. E poi vi sono quelle voci fuori dal coro che si pongono in modo ironico nei confronti della storia e ipotizzano possibilità impensate in virtù delle quali mostrano un concetto diverso e una sottile critica nei confronti della società attuale e passata e che concretizzano con uno stile inedito e accattivante. Il protagonista di oggi appartiene a questo gruppo di artisti.

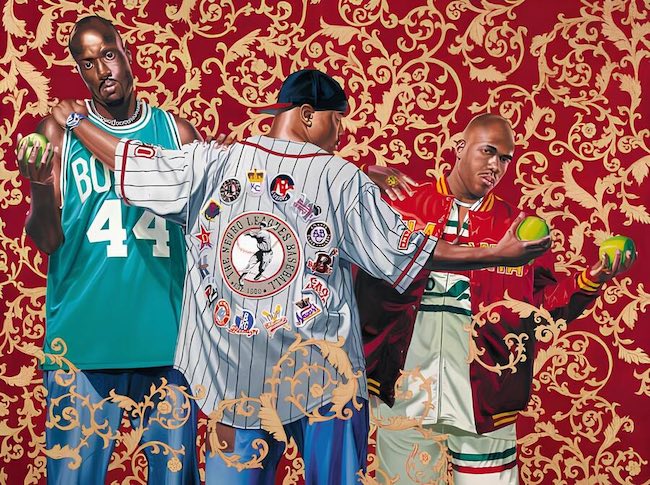

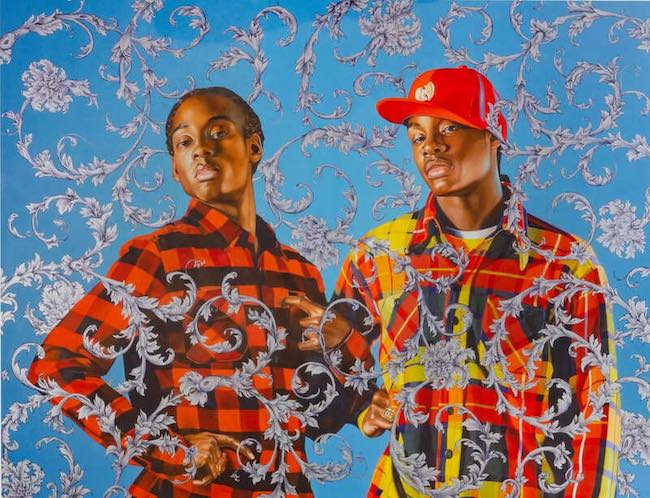

Intorno alla metà del Novecento cominciarono a emergere movimenti pittorici che recuperarono quella figurazione in precedenza ripudiata per dare spazio alla scoperta della non forma come massima espressione dell’autonomia dal gesto plastico rispetto alla realtà osservata, come supremazia dell’atto creativo in sé prescindendo da ciò che lo sguardo era abituato a vedere nella quotidianità. Le nuove correnti artistiche degli anni Cinquanta del Ventesimo secolo andarono verso due diverse e opposte direzioni: quella della riproduzione fedele ed esatta, esteticamente perfetta e fotografica dell’osservato, che prese il nome di Iperrealismo, e quella dell’irridente evidenziazione delle abitudini della società borghese e consumistica dell’epoca, con le sue debolezze e il suo bisogno di entrare in un mondo dell’arte fino a poco prima completamente ignorato dalla nuova classe emergente, che venne per questo denominata Pop Art. L’Iperrealismo volle riprodurre fedelmente gli scorci delle metropoli statunitensi, la bellezza quasi algida dei grattacieli e delle pareti a specchio, gli oggetti delle tavole calde, senza preoccuparsi di infondere emozione bensì solo con l’intento di riprodurre fedelmente la realtà; eppure le incredibili opere di Richard Estes, più concentrato sulle superfici lucide dei palazzi, sui sedili in plastica con vedute sulla città degli autobus newyorkesi e sulle cabine telefoniche, e quelle di Ralph Goings, orientato invece a mettere in risalto i luoghi dove le persone erano abituate a consumare i propri pasti, le cosiddette tavole calde, anticipatrici dei fast food, così come i cibi tipici che lì si consumavano, ebbero un successo planetario proprio grazie alla capacità di questi grandi artisti di parlare il linguaggio delle persone comuni, lo stesso che esse vivevano ogni giorno, ritrovandosi in quelle immagini. La Pop Art invece, che a sua volta comprese l’importanza di rivolgersi alla nuova classe media emergente priva di cultura di base necessaria a comprendere un tipo di arte più intellettuale ma con sufficiente capacità economica da potersi permettere di acquistare un’opera, scelse di avvalersi di linguaggi espressivi facilmente comprensibili e popolari ma in maniera irriverente, giocosa, e di rendere protagoniste le icone del cinema e i materiali di consumo di Andy Warhol, i personaggi dei fumetti di Roy Licthenstein e di Steve Kaufman, gli scorci di vita quotidiana raccontati con elementi di collage e arricchiti dalla presenza decontestualizzata di personaggi del cinema di Richard Hamilton o quelli eseguiti in stile quasi grafico e fumettistico di David Hockney. Entrambi gli stili avevano come denominatore comune quello di andare verso il pubblico, di volersi avvicinare a una nuova società destinata a rompere gli schemi e il divario tra aristocrazia e classe operaia, che apprezzò tutti questi artisti fino a decretarne l’enorme successo. L’artista afroamericano Kehinde Whiley mescola i due linguaggi pittorici, l’Iperrealismo e la Pop Art, che utilizza in modo insolito dando una nuova linfa al modo di intendere il ritratto, contraddistinto da sfondi che richiamano le decorazioni delle carte da parati su cui si stagliano i suoi protagonisti.

Ma ciò che rende questo artista davvero unico sono due caratteristiche inusuali; la prima è quella di scegliere sempre persone afroamericane, come a sottolineare quanto tutta la storia dell’arte, tranne qualche raro caso, sia sempre stata piena di personaggi con tratti caucasici, spesso diafani, senza mai prendere in considerazione altre etnie se non nell’arte orientale e in quella indigena, che hanno però solo in alcuni rari casi raggiunto il successo internazionale degli artisti occidentali.

La seconda, quella che forse manda il messaggio più forte, è di prendere come spunto grandi opere dell’arte tradizionale, le più celebri, facendo mettere in posa i suoi personaggi afroamericani come gli eroi di pelle bianca del passato, quasi a sovvertire le regole di una narrazione che avrebbe anche potuto essere diversa, quasi a voler sottolineare e mettere in evidenza quanto tutto ciò che è stato quasi sempre appannaggio della razza bianca oggi può essere eradicato e rivisitato con un punto di vista differente.

Kehinde Whiley ha un approccio ironico all’arte, ammirato nei confronti della sua gente, quella che ha tutti i diritti di avere un posto di primo piano nel panorama artistico, e così sceglie un modo per renderla protagonista anche di un passato glorioso in cui è stata assente, di cui non ha fatto parte perché i tempi non erano maturi, perché non ha avuto le stesse opportunità di poter divenire icona dei grandi maestri, e trasforma le persone di strada, a volte vestite con gli abiti che abitualmente indossano, altre invece abbigliate con vesti affini a quelle delle opere originali a cui si rifà.

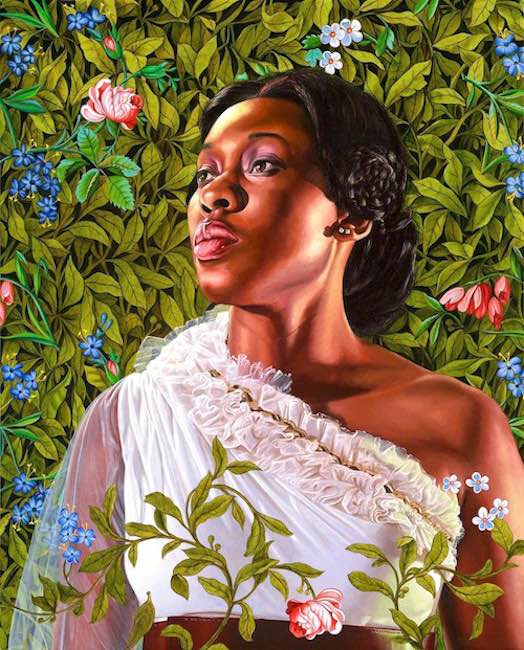

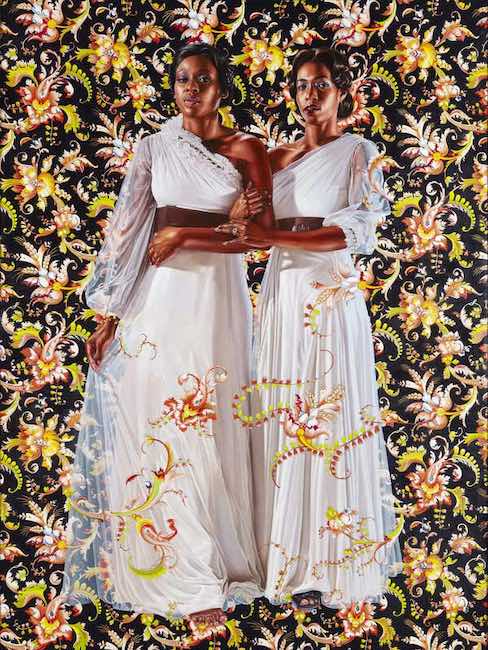

Il dipinto The Two Sisters, ispirato all’opera dell’artista esponente del Romanticismo Theodore Chasseriau, ripropone la delicatezza della posa delle donne, abbigliate con vesti bianche in contrasto con il colore della pelle e la medesima espressione timida, quasi insicura nel sentirsi osservate e in procinto di essere protagoniste di un pezzo d’arte; l’Iperrealismo utilizzato per riprodurre perfettamente i volti e gli abiti delle ragazze si mescola alla decontestualizzazione Pop di uno sfondo floreale che addirittura osa spingersi fino alla parte inferiore delle gonne, quasi a voler sottolineare l’irrealtà della composizione ma anche in fondo l’apertura al fatto che tutto sia possibile e avere un aspetto differente da quello a cui da sempre si è abituati.

In Officer of the Hussars, Kehinde Whiley osa persino di più perché pone un afroamericano vestito in jeans e canottiera nella medesima posa della tela originale, con lo stesso titolo di quella del pittore romantico Theodore Gericault che riproduce un ufficiale di cavalleria napoleonico; nella contemporaneità l’ufficiale non è un militare bensì un uomo comune, un eroe della vita quotidiana che spesso si trova a combattere battaglie persino più complesse e che per questo merita di essere celebrato tanto quanto un uomo che ha combattuto in guerra. L’orgoglio nello sguardo del giovane protagonista della tela di Whiley rappresenta la soddisfazione nell’avere finalmente un ruolo di primo piano, per vedersi riconosciuto il diritto di diventare, nel suo essere comune, immortale in virtù dell’arte.

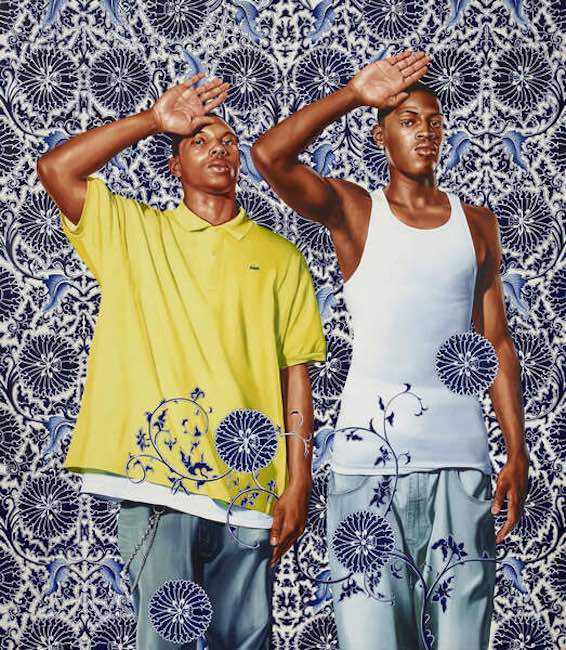

Nel dipinto Two Heroic Sisters of the Grasslands invece, l’artista rivisita un manifesto di propaganda della Repubblica Popolare Cinese del 1965 che esaltava il gesto eroico di due sorelle originarie della Mongolia che hanno rischiato le loro vite per proteggere le pecore della loro comune durante una tempesta di neve; nella tela di Whiley emerge la medesima stima nei ragazzi protagonisti, sconosciuti eppure simbolo anche loro della resistenza del loro popolo che ha dovuto subire emarginazioni e rifiuto da parte della società bianca, quella che aveva il potere negli Stati Uniti, per molti anni fino a quando il coraggio e la forza di combattere per i propri diritti non ha scalfito il sistema permettendo agli afroamericani di emergere dall’ombra e perseguire i propri sogni come chiunque altro. Anche in questo caso i due ragazzi indossano abiti comuni, quelli della strada, quelli con cui si intrattengono a giocare a basket con gli amici o a divertirsi cantando il rap; sembra giocare con gli stereotipi Kehinde Whiley, li prende, li immortala e poi li trasforma, suggerendo che l’apparenza esteriore non conta, ciò che conta è l’essenza e quella non ha razza, né religione, né colore, è semplicemente manifestazione dell’interiorità.

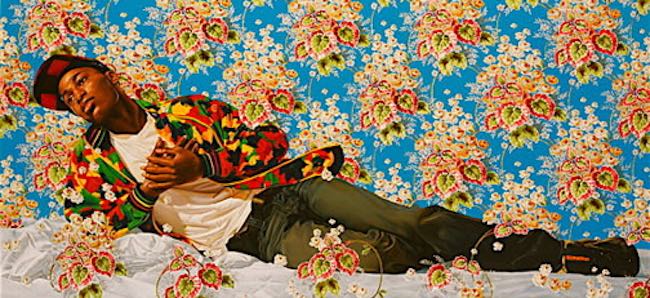

E ancora in Christian Martyr Tarcisius Whiley si ispira alla scultura di Alexandre Falguière proponendo il suo protagonista afroamericano in una posa meno sofferente rispetto all’originale, e tuttavia ugualmente intensa, più nostalgica, quasi sospirante nei confronti di qualcosa che desidera ma che ancora non è riuscito a ottenere; il parallelismo tra il ragazzino che si è fatto picchiare pur di proteggere i sacramenti che aveva con sé, e l’uomo di colore, inteso come popolo, che ha dovuto subire in passato ogni genere di sofferenza e di discriminazione, è intenso e colpisce l’interiorità, che pur si distrae un attimo dopo con lo sfondo fiorato che stempera la gravità dell’atmosfera e che rende Pop l’insieme. Kehinde Whiley ha ricevuto il suo MFA da Yale nel 2001 e ha esposto a New York, Los Angeles, Parigi, Berlino e Milano, tra le altre città. Il suo lavoro appartiene alle collezioni del Metropolitan Museum of Art, del Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles e del Nasher Museum of Art, e i suoi dipinti sono stati venduti a sei cifre sul mercato secondario.

KEHINDE WHILEY-CONTATTI

Email: kat@kehindewiley.com

Sito web: https://kehindewiley.com

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100044507078357

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/kehindewiley/

Kehinde Whiley, art classics revisited in a Hyperrealist Pop key and with African-American pride

Very often, the need to look at and rework the artistic past results in a stance by contemporary creatives through which they place themselves in a position of admiration, rejection or even contestation of all points of view, pictorial approaches and the narrative that has been made of reality. And then there are those voices out of the chorus that pose ironically in relation to history and hypothesise unthought-of possibilities by virtue of which they show a different concept and a subtle critique of current and past society, and which they realise with an unprecedented and captivating style. Today’s protagonist belongs to this group of artists.

Around the middle of the 20th century, began to emerge pictorial movements that recovered that previously repudiated figuration to make room for the discovery of non-form as the utmost expression of the autonomy of the plastic gesture with respect to the observed reality, as the supremacy of the creative act in itself, prescinding from what the eye was accustomed to seeing in everyday life. The new artistic currents of the 1950s moved in two different and opposing directions: that of the faithful and exact, aesthetically perfect and photographic reproduction of the observed, which took the name of Hyperrealism, and that of the irreverent highlighting of the habits of the bourgeois and consumerist society of the time, with its weaknesses and its need to enter an art world that had until recently been completely ignored by the newly emerging class, which was therefore called Pop Art. Hyperrealism wanted to faithfully reproduce the views of American metropolises, the almost algid beauty of skyscrapers and mirrored walls, the objects in the cafeterias, without worrying about infusing emotion but only with the intention of faithfully reproducing reality; and yet the incredible artworks of Richard Estes, more focused on the surfaces of buildings, plastic seats with city views of New York buses and telephone booths, and those of Ralph Goings, oriented instead towards highlighting the places where people used to eat their meals, the so-called diners, the forerunners of fast food, as well as the typical foods that were eaten there, enjoyed worldwide success precisely because of the ability of these great artists to speak the language of ordinary people, the same that they lived every day, finding themselves in those images.

Pop Art, on the other hand, which in turn understood the importance of addressing the newly emerging middle class lacking the basic culture necessary to understand a more intellectual type of art but with sufficient economic capacity to be able to afford to buy an artwork, chose to make use of easily understandable and popular expressive languages but in an irreverent manner, playful way, and to make protagonists of Andy Warhol‘s film icons and consumables, Roy Licthenstein‘s and Steve Kaufman‘s comic strip characters, the glimpses of everyday life told with collage elements and enriched by the decontextualised presence of film characters by Richard Hamilton, or those executed in an almost graphic and comic style by David Hockney. Both styles had as their common denominator that of reaching out to the public, of wanting to approach a new society destined to break the mould and the gap between the aristocracy and the working class, which appreciated all these artists to the point of decreeing their enormous success. The African-American artist Kehinde Whiley mixed the two pictorial languages, Hyperrealism and Pop Art, which he used in an unusual way, giving a new lease of life to the way of intending portraits, characterised by backgrounds that recall the wallpaper decorations on which his protagonists stand out. But what makes this artist truly unique are two unusual particularities; the first is that he always chooses African-American people, as if to emphasise how the entire history of art, except for a few rare cases, has always been full of characters with Caucasian features, often diaphanous, without ever taking other ethnicities into consideration except in Oriental and indigenous art, which have however only in some rare cases achieved the international success of Western artists. The second, the one that perhaps sends the strongest message, is to take great works of traditional art, the most famous ones, as a cue, by posing his African-American characters as the white-skinned heroes of the past, almost as if to subvert the rules of a narrative that could also have been different, almost as if to emphasise and highlight how everything that has almost always been the prerogative of the white race can now be eradicated and revisited with a different point of view.

Kehinde Whiley has an ironic approach to art, admiring towards his people, those who have every right to have a prominent place in the artistic panorama, and so he chooses a way to make them protagonists even of a glorious past in which they were absent, of which they were not a part because the time was not ripe, because they did not have the same opportunities to become icons of the great masters, and transforms the people in the street, sometimes dressed in the clothes they usually wear, others in clothes similar to those of the original artworks to which he refers. The painting The Two Sisters, inspired by the work of the Romanticist artist Theodore Chasseriau, re-proposes the delicacy of the women’s pose, dressed in white robes that contrast with the colour of their skin, and the same shy, almost insecure expression as they feel observed and about to be the protagonists of a piece of art; the Hyperrealism used to perfectly reproduce the girls’ faces and dresses is mixed with Pop‘s decontextualisation of a floral background that even dares to go as far as the bottom of their skirts, almost as if to emphasise the unreality of the composition but also, at bottom, the openness to the fact that everything is possible and looks different from what we have always been used to. In Officer of the Hussars, Kehinde Whiley dares even more because he places an African-American man dressed in jeans and a tank top in the same pose as the original canvas, with the same title as that of the Romantic painter Theodore Gericault‘s depiction of a Napoleonic cavalry officer; in the contemporary world, the officer is not a soldier but an ordinary man, a hero of everyday life who often finds himself fighting even more complex battles and that for this he deserves to be celebrated as much as a man who has fought in the war. The pride in the gaze of the young protagonist of Whiley‘s canvas represents the satisfaction at finally having a leading role, at having his right to become immortal by virtue of art.

In the painting Two heroic sisters of the Grasslands, on the other hand, the artist revisits a 1965 People’s Republic of China propaganda poster extolling the heroic gesture of two sisters from Mongolia who risked their lives to protect their commune’s sheep during a snowstorm; in Whiley‘s canvas, the same esteem emerges in the young protagonists, unknown and yet also a symbol of the resistance of their people who had to endure marginalisation and rejection by white society, the society that had power in the United States, for many years until the courage and strength to fight for their rights did not make a dent in the system, allowing African-Americans to emerge from the shadows and pursue their dreams like anyone else. Again, the two boys wear ordinary clothes, the ones of the street, those they wear to play basketball with friends or to have fun singing rap; Kehinde Whiley seems to be playing with stereotypes, taking, immortalising and then transforming them, suggesting that outward appearance does not count, what counts is essence and that has no race, no religion, no colour, it is simply the manifestation of inwardness. And again in Christian Martyr Tarcisius Whiley is inspired by Alexandre Falguière‘s sculpture, proposing his African-American protagonist in a pose that is less suffering than the original, and yet equally intense, more nostalgic, almost sighing towards something he desires but has not yet managed to obtain; the parallelism between the little boy who let himself be beaten up in order to protect the sacraments he had with him, and the black man, understood as a people, who has had to suffer all kinds of suffering and discrimination in the past, is intense and affects the interiority, which is nevertheless distracted a moment later by the flowery background that dilutes the seriousness of the atmosphere and makes the whole pop. Kehinde Whiley received her MFA from Yale in 2001 and has exhibited in New York, Los Angeles, Paris, Berlin and Milan, among other cities. His artworks belongs to the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles and the Nasher Museum of Art, and his paintings have sold for six figures on the secondary market.