L’arte contemporanea spesso è una manifestazione interiore, un modo per comunicare tutto ciò che la coscienza e la razionalità non sarebbero in grado di spiegare né di rappresentare proprio perché appartenente alla dimensione dell’impulso che se da un lato è in grado di influenzare il comportamento quotidiano e l’approccio alla vita, dall’altro non può essere filtrato dalla ragione. Lo stile pittorico più affine a questo tipo di intenzione artistica è senza alcun dubbio quello che rinuncia alla rappresentazione della realtà e si inoltra nelle pieghe della non forma, proprio perché è attraverso l’indefinitezza che le emozioni possono trovare una loro concretezza e affiorare alla piena coscienza della loro forza. La protagonista di oggi appartiene a questo gruppo di creativi, e attraverso l’espressività artistica impulsiva, irrazionale, ha approfondito la conoscenza di se stessa e dell’alchemico mondo delle emozioni.

Il mondo interiore, quell’universo segreto e tumultuoso che da sempre appartiene all’essere umano, è stato lungamente escluso dall’arte poiché le regole accademiche si concentravano prevalentemente sulla perfezione, sull’equilibrio estetico e formale, sulla riproduzione esatta e dettagliata di tutto ciò che l’occhio poteva cogliere nella realtà; questo tipo di schema artistico escludeva la soggettività dell’autore di un’opera che poteva inserire solo il tocco personale e la maestria esecutiva, distinguendosi così dai colleghi, ma senza immettere nella tela il suo sentire e le sue emozioni. Gli inizi del Novecento però rivoluzionarono l’intero mondo creativo, il modo di intendere la pittura dando maggiore rilevanza a tutta quell’interiorità precedentemente esclusa, soprattutto attraverso un utilizzo del colore completamente divergente dalla tecnica e dalle regole esecutive fino a poco prima prioritarie; furono inizialmente i Fauves, un gruppo che non riuscì mai a diventare un vero e proprio movimento, a sovvertire ogni regola cromatica associando tonalità forti alle sensazioni percepite dall’esecutore. Dunque i dipinti di Henri Matisse, nella sua prima fase pittorica, di André Derain e di Maurice de Vlaminck, apparivano violenti e aggressivi agli occhi dei frequentatori dei salotti culturali dell’epoca, proprio a causa della loro intensità e irrealtà funzionali a legarsi unicamente al mondo interiore. Quella scelta di libertà espressiva non solo fu motore propulsivo per l’appena successivo Espressionismo, che si diffuse nell’intero continente europeo declinandosi dal punto di vista formale secondo il retaggio culturale dei singoli paesi di provenienza degli artisti, ma divenne la base per la successiva reinterpretazione statunitense di uno stile informale, in precedenza distaccato dall’emozionalità, che doveva essere indissolubilmente legato alla soggettività intima dell’esecutore dell’opera. Jackson Pollock e i suoi colleghi irascibili mostrarono nel desiderio di affermarsi e di veder considerata la loro corrente, l’Espressionismo Astratto, anche nei conservatori salotti americani, tutto l’impeto emozionale di cui erano capaci e di cui erano intrise le loro tele, sia che adottassero il Dripping, caro proprio a Pollock, sia che si orientassero alla manifestazione più contemplativa come nel Color Field di Mark Rothko e di Clyfford Still, oppure alla pittura segnica e gestuale di Franz Kline e Willem De Kooning o ancora alla monocromia di Barnett Newman.

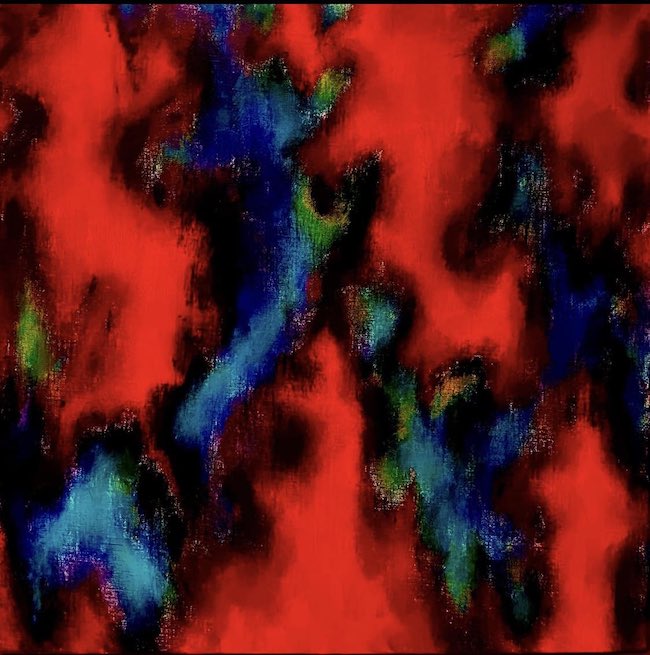

L’artista coreana Susanna Yang ripercorre lo scopo primario dell’Espressionismo Astratto e lo utilizza come linguaggio creativo quasi inconsapevole, perché la sua esigenza istintiva è quella di liberare tutto ciò che sente ruotare all’interno di sé e che non può essere contenuto, né spiegato, dalla ragione; completamente autodidatta sceglie di lasciarsi guidare dall’energia del colore, avvicinandosi al Color Field a macchie di Clyfford Still, per dare voce alle sue pulsioni più profonde, trasformando il gesto pittorico in manifestazione delle passioni, intese nell’accezione più ampia del termine, che non potevano più essere trattenute. Dunque la pittura assume per lei un ruolo curativo, una catarsi che funge da valvola comunicativa di tutte quelle tempeste interiori che affiorano in superficie e devono fuoriuscire per liberare l’anima da tutto ciò che diversamente potrebbe opprimerla; la tonalità predominante è pertanto il rosso, il colore associato all’energia, alla passione, alla determinazione, al coraggio di fronteggiare le proprie insicurezze, le proprie paure, e trasformale in un punto di forza.

È stato esattamente l’impulso dell’anima, l’esigenza di espellere tutto ciò che in qualche modo bloccava la sua serenità e il suo equilibrio a spingere Susanna Yang a dipingere, a dispetto della sua mancanza di formazione specifica e solo con il bisogno di stare davanti alla tela e ai i colori per lasciarsi andare a quel processo quasi inconsapevole che contraddistingue l’Arte Informale e grazie al quale l’artista può raggiungere un equilibrio che diversamente la costringerebbe a essere sbilanciata a causa delle emozioni trattenute.

Altre tonalità predominanti solo il giallo, che corrisponde alla vitalità, alla speranza e all’allegria, e l’azzurro, che si lega invece alla spiritualità, all’universalità, alla trascendenza, entrambi indicativi del necessario percorso della Yang per raggiungere una consapevolezza di sé e una liberazione interiore funzionali alla sua evoluzione come individuo.

L’opera Desire sembra essere una poetica visione di un sentimento struggente, di mancanza di ciò che si necessita per sentirsi felici e appagati, e al contempo anche una dedica poetica a un’emozione in grado di avvolgere l’anima e travolgere i sensi, in virtù di quella fase di aspettativa che segue o che precede l’incontro con la persona che suscita quella sensazione. Il rosso si mescola all’azzurro come se in qualche modo l’attesa rendesse più morbido e spirituale la pausa che precede il momento del sopraggiungere di ciò che il protagonista dell’emozione aspetta con trepidazione, al contempo il rosso riempie di energia e di determinazione la sensazione del desiderare, come se fosse proprio dall’ambivalenza tra le due parti, quella più spirituale e quella più concreta, che si amplificasse il sentire.

In My great life invece Susanna Yang non si limita solo a giocare con la spiritualità e il sogno, definiti dall’azzurro, e con la forza propulsiva e quasi travolgente del rosso, bensì introduce anche il violetto legato all’anima, alle sue pulsioni silenziose, all’ascolto di quelle vibrazioni sottili che spesso sanno esattamente dove condurre se si comprende la rilevanza del loro sussurrato messaggio. Questa tela è particolarmente autobiografica poiché è proprio grazie al coraggio e alla risolutezza nel perseguire il suo desiderio di essere un’artista che Susanna Yang ha fortemente voluto cominciare a dipingere, a dispetto delle limitazioni, dei pregiudizi intorno a sé che volevano in qualche modo soffocare la sua spinta creativa a causa della mancanza di una formazione accademica, e lasciandosi guidare dalla forza di rompere quella barriera di silenzio interiore che in precedenza avvolgeva la sua vera essenza. È solo attraverso l’unione delle molteplici sfaccettature della propria natura, la comprensione e l’accettazione delle differenti parti di sé, quella più impulsiva, quella riflessiva e quella sognante, che è possibile raggiungere un equilibrio in grado di tenere in piedi l’individuo e di sostenerlo nelle avversità.

La tela The promise (Passion for you) sembra dunque essere una sintesi di questo percorso aperto all’imprevisto, alla felicità di abbracciare una promessa che può essere stata ricevuta da un uomo o da qualcuno all’esterno del sé, oppure è un dialogo interiore con quel lato insicuro e spaventato che non avrebbe mai previsto di essere in grado di raggiungere e realizzare i propri sogni. In entrambe le opzioni, un amore coinvolgente e destabilizzante oppure un’autorealizzazione necessaria a rinforzare e curare il proprio ego, l’emozione che si genera è quella della gioiosità, della felicità sorridente che si percepisce in virtù della presenza del giallo, colore solare e caldo esattamente come le sensazioni che derivano dalla coscienza di avere ciò per cui si è lottato. Dunque l’Espressionismo Astratto assume in Susanna Yang tinte intimiste, un bilanciamento tra istinto e riflessione, tra impulso primordiale e morbidezza di un’anima sensibile e proprio per questo bisognosa di concretizzare sulla tela le emozioni più profonde.

Dal 2007 Susanna Yang ha aperto una sua galleria in Corea dove genera una sinergia tra arte e moda attraendo un interessato pubblico di collezionisti appassionati della sua maestria nell’utilizzo del colore; negli ultimi anni ha cominciato a seguire un percorso espositivo internazionale, mostrando le sue opere in gallerie e spazi istituzionali in Italia, a Parigi e a New York.

Marta Lock

SUSANNA YANG-CONTATTI

Email: herosk1539@naver.com

Facebook: www.facebook.com/suwaart

Instagram: www.instagram.com/cheongcho_susanna/

The regenerative and healing power of passion in Abstract Expressionism by Susanna Yang

Contemporary art is often an inner manifestation, a way of communicating all that conscience and rationality would not be able to explain or represent precisely because it belongs to the dimension of impulse that, while it is able to influence everyday behaviour and approach to life, cannot be filtered by reason. The style of painting most akin to this type of artistic intention is undoubtedly that which renounces the representation of reality and enters into the folds of non-form, precisely because it is through indefiniteness that emotions can find their concreteness and emerge to the full consciousness of their power. Today’s protagonist belongs to this group of creatives, and through impulsive, irrational artistic expressiveness, she has deepened her knowledge of herself and the alchemic world of emotions.

The inner world, that secret and tumultuous universe that has always belonged to the human being, was excluded from art for a long time because the academic rules concentrated mainly on perfection, on aesthetic and formal balance, on the exact and detailed reproduction of everything the eye could grasp in reality; this type of artistic scheme excluded the subjectivity of the author of an artwork who could only insert his personal touch and executive mastery, thus distinguishing himself from his colleagues, but without putting his feelings and emotions onto the canvas. The beginning of the 20th century, however, revolutionised the entire creative world, the way of understanding painting, giving greater relevance to all that interiority previously excluded, above all through a use of colour that completely diverged from the technique and executive rules that had been prioritised until a short time before; it was initially the Fauves, a group that never managed to become a real movement, who subverted all chromatic rules by associating strong tones with the sensations perceived by the executor. Thus, the paintings of Henri Matisse, in his early pictorial phase, of André Derain and Maurice de Vlaminck, appeared violent and aggressive in the eyes of the frequenters of the cultural salons of the time, precisely because of their intensity and unreality that only served to bind them to the inner world. That choice of expressive freedom was not only a driving force for the just subsequent Expressionism, which spread across the entire European continent declining in formal terms according to the cultural heritage of the artists’ individual countries of origin, but also became the basis for the subsequent American reinterpretation of an informal style, previously detached from emotionality, that was to be inextricably linked to the intimate subjectivity of the artwork’s author. Jackson Pollock and his irascible colleagues showed all the emotional impetus they were capable of and with which their canvases were imbued, in their desire to assert themselves and have their current, Abstract Expressionism, considered even in the conservative American salons, whether they adopted Dripping, dear to Pollock himself, or whether they turned to a more contemplative manifestation as in Mark Rothko‘s and Clyfford Still‘s Colour Field, or to the sign and gesture painting of Franz Kline and Willem De Kooning or again to Barnett Newman‘s monochrome.

Korean artist Susanna Yang retraces the primary purpose of Abstract Expressionism and uses it as an almost unconscious creative language, because her instinctive need is to release all that she feels revolving within herself and that cannot be contained, nor explained, by reason; completely self-taught, she chooses to let herself be guided by the energy of colour, approaching Clyfford Still‘s spot Color Field, to give voice to her deepest impulses, transforming the pictorial gesture into a manifestation of the passions, understood in the broadest sense of the term, that could no longer be restrained. Hence painting takes on a curative role for her, a catharsis that acts as a communicative valve for all those inner storms that surface and must come out to free the soul from everything that might otherwise oppress it; the predominant shade is therefore red, the colour associated with energy, passion, determination, the courage to face one’s insecurities, one’s fears, and transform them into a point of strength. It was exactly the impulse of the soul, the need to expel everything that in some way blocked her serenity and balance that drove Susanna Yang to paint, in spite of her lack of specific training and only with the need to stand in front of the canvas and colours to let herself go in that almost unconscious process that characterises Informal Art and thanks to which the artist can achieve a balance that would otherwise force her to be unbalanced due to withheld emotions. Other predominant tones are yellow, which corresponds to vitality, hope and cheerfulness, and light blue, which is linked instead to spirituality, universality and transcendence, both indicative of the Yang‘s necessary journey to achieve a self-awareness and inner liberation that is functional to her evolution as an individual.

The painting Desire seems to be a poetic vision of a poignant feeling, of the lack of what one needs to feel happy and fulfilled, and at the same time also a poetic dedication to an emotion capable of enveloping the soul and overwhelming the senses, by virtue of that phase of expectation that follows or precedes the meeting with the person who arouses that sensation. Red is mixed with blue as if in some way the expectation would soften and spiritualise the pause that precedes the moment of the arrival of what the protagonist of the emotion is anxiously awaiting, at the same time red fills the sensation of desire with energy and determination, as if it were from the ambivalence between the two parts, the more spiritual and the more concrete, that the feeling is amplified. In My great life, on the other hand, Susanna Yang does not limit herself to playing with spirituality and dreams, defined by blue, and with the propulsive and almost overwhelming force of red, but also introduces the violet linked to the soul, to its silent impulses, to listening to those subtle vibrations that often know exactly where to lead if one understands the relevance of their whispered message. This canvas is particularly autobiographical because it is thanks to her courage and resolution in pursuing her desire to be an artist that Susanna Yang strongly wanted to start painting, in spite of the limitations, the prejudices around her that wanted to somehow stifle her creative drive due to her lack of academic training, and letting herself be guided by the strength to break through that barrier of inner silence that previously shrouded her true essence. It is only through the union of the many facets of one’s nature, the understanding and acceptance of the different parts of oneself, the more impulsive, the reflective and the dreamy, that it is possible to achieve a balance capable of holding the individual up and sustaining him in adversity. The canvas The promise (Passion for you) thus seems to be a synthesis of this path open to the unexpected, to the happiness of embracing a promise that may have been received from a man or someone outside the self, or it is an inner dialogue with that insecure and frightened side that never expected to be able to achieve and realise its dreams.

In both options, an enthralling and destabilising love or a self-realisation necessary to reinforce and cure one’s ego, the emotion generated is that of joyfulness, of smiling happiness that is perceived by virtue of the presence of yellow, a colour that is sunny and warm exactly like the sensations that derive from the consciousness of having what one has fought for. Thus, Abstract Expressionism takes on intimist tones in Susanna Yang, a balance between instinct and reflection, between primordial impulse and the softness of a sensitive soul and for this very reason in need of concretising her deepest emotions on canvas. Since 2007, Susanna Yang has opened her own gallery in Korea where she generates a synergy between art and fashion, attracting an interested public of collectors who are passionate about her mastery in the use of colour. In recent years, she has started to follow an international exhibition path, showing her artworks in galleries and institutional spaces in Italy, Paris and New York.