Il mondo degli oggetti che appartengono al quotidiano è stato argomento di studio e di approfondimento di molti artisti dei secoli precedenti e si è concretizzato nell’arte contemporanea nella tendenza a dare risalto a tutto ciò che sarebbe diversamente considerato un semplice strumento di utilizzo funzionale e che trasforma invece la sua essenza grazie allo sguardo dell’artista. Nel caso del protagonista di oggi le cose inanimate assumono quasi un aspetto animato, come se la loro presenza nello spazio costituisse un modo per mostrarsi, per sottolineare il loro esistere, per affermare una nascosta e improbabile personalità in grado di fuoriuscire dall’opera mettendosi in comunicazione con l’osservatore.

Con la nascita dell’Espressionismo, tra fine Ottocento e i primi anni del Novecento, tutti gli oggetti e i luoghi in cui l’essere umano si muoveva cominciarono a divenire essenziali coprotagonisti delle opere, sia per la loro rilevanza nel vissuto ordinario sia per la capacità di assorbire le emozioni e le sensazioni emanate dei personaggi ritratti o dai paesaggi immortalati dai grandi protagonisti di questa corrente artistica. A partire dalla sperimentazione e dalle teorie dei Fauves, che furono la base da cui vennero delineate le linee guida dell’Espressionismo, l’attenzione alla semplicità emozionale di tutto ciò che circondava l’essere umano, comprese quelle rassicurazioni costituite da ambienti e oggetti di uso quotidiano, divenne parte integrante dell’approccio pittorico e della propagazione delle sensazioni percepite, protagoniste di fatto delle tele dei maggiori esponenti di quegli inizi di rivoluzione espressiva, tra cui Henri Matisse, Maurice De Vlamink e André Derain. Gli interni dettagliati e contraddistinti da colori saturi e intensi di Matisse raccontavano di un attaccamento a tutte quelle cose che appartenevano alla sua routine, o a quella dei suoi protagonisti, e da cui nessuno era in grado di prescindere proprio perché a essi si legavano sensazioni rassicuranti, avvolgenti proprio per la loro costante presenza, per il loro essere parte dello scorrere del tempo, protagonisti di azioni quasi automatiche senza i quali le certezze sarebbero venute meno. Laddove Matisse poneva in primo piano l’intero ambiente, i particolari ma anche le stanze o gli angoli in cui gli oggetti erano contenuti, l’altro grande esponente del movimento dei Fauves, Maurice De Vlamink, poneva invece in luce il singolo oggetto, o la composizione, astraendolo dallo sfondo come se quest’ultimo non fosse fondamentale bensì dovesse solo essere una indefinita base per mettere in risalto l’immagine in primo piano. Quando invece decideva di allargare lo sguardo alla totalità di un luogo chiuso, di una camera o di una stanza, non poteva fare a meno di introdurre la figura umana, sottolineando quanto per lui l’oggetto fosse legato all’utilizzante, tanto quanto l’emozione suscitata e diffusa verso gli oggetti non potesse prescindere da chi la provava. L’artista laziale Faustino Roncoroni si lega fortemente all’Espressionismo, e a tratti ai Fauves, sia per le sue tonalità emozionali, connesse con il ventaglio di sensazioni che l’uomo avverte e che tutto ciò che lo circonda riflette, sia per la particolarità di dare risalto alle cose che riempiono la vita di ciascuno, a quei prodotti, a quegli articoli che sono fondamentali per permettere di compiere i semplici gesti della routine, per connettersi ai ricordi, e restare legati a un’abitudine che rasserena.

Eppure in quell’immobilità apparente l’artista sembra sottintendere la vitalità di quegli oggetti, come se essi stessi avessero una vita propria all’interno della quale giocano a nascondersi, a sparire per essere ricercati, ed è proprio questa la sensazione che Roncoroni suscita nell’osservatore, quella di dover lasciar vagare lo sguardo sulla tela per riconoscere quei dettagli familiari, per trovare quel particolare libro, quella coperta, vaso o bicchiere in virtù del quale sentirsi a casa, come se quel disordine di cui narrano le opere dell’artista corrispondesse in fondo alla confusione che spesso assale la mente umana e che necessita di perdersi nel caos prima di riuscire a dare un ordine alle idee e da lì in avanti proseguire con maggiore consapevolezza.

La prospettiva, spesso inesistente nelle linee guida dell’Espressionismo, in Roncoroni diviene funzionale a nascondere e accatastare gli oggetti necessitando perciò dei livelli di profondità all’interno dei quali porre e lasciar intravedere spigoli, dettagli, particolari attraverso cui l’artista guida lo sguardo dell’osservatore alla scoperta di ciò che va oltre l’apparenza immediata. La narrazione non ha nulla di romantico, di poetico come nelle opere dei maestri del Novecento bensì entra nella contemporaneità raccontando tutto ciò che fa parte del vivere attuale pur enfatizzando l’importanza della cultura, quel riempire le stanze osservate di scaffali pieni di libri per indurre l’osservatore a non dimenticare né tralasciare l’importanza della conoscenza, sia essa del presente, della storia o di qualsiasi argomento che abbia bisogno di approfondimento.

Nella tela Stanza di Roma, Faustino Roncoroni si lascia letteralmente affascinare, avvolgere da tutto ciò che trova davanti ai suoi occhi, ciascun elemento è complementare al successivo come se l’uno avesse bisogno dell’altro per esistere, come se la presenza dello schermo del pc fosse indivisibile da quello della sedia di fronte, come se lo specchio fosse funzionale a mettere in evidenza tutto ciò che si trova al di sotto. Gli elementi della composizione dialogano tra loro rimandando all’osservatore un’immagine divertita e divertente che lo fa sentire coinvolto esattamente in virtù di quella confusione, di quell’accostamento di forte impatto che tutto sommato somiglia alle stanze di lavoro della maggior parte delle persone, quell’ordinato caos in cui tutto può essere trovato perché affine alla personalità e al processo mentale del possedente gli oggetti.

In Dopo il trasloco l’artista racconta il senso di disorientamento che si è costretti ad affrontare a seguito di uno spostamento, di un cambiamento radicale in cui sono proprio gli oggetti gli unici a costituire le certezze e a dare la possibilità di ricostruire un’atmosfera che in fondo non appartiene a un luogo bensì al bagaglio emotivo, ed è in questo che le cose si legano alle sensazioni, che segue l’essere umano ovunque scelga di vivere. Il disordine descritto da Roncoroni corrisponde al disorientamento emozionale che ciascuna modificazione, ogni trasformazione, porta con sé, malgrado la consapevolezza, costituita dalla razionalità delle cose possedute, che alcuni passaggi siano necessari per andare verso un nuovo domani. Le tonalità si accordano così all’entusiasmo di quel nuovo cammino, alla vivacità che inevitabilmente avvolge nel momento appena successivo alla scelta di staccarsi dal passato, al calore del desiderare di ricostruire nuove sicurezze e nuove rassicurazioni avvalendosi di ciò che di quel passato si è voluto conservare.

Quando esce dagli interni e racconta paesaggi e scorci Faustino Roncoroni si lascia influenzare dallo stile intenso di André Derain ma anche dall’irrealtà sospesa di Maurice De Vlamink, realizzando una sintesi in cui le tonalità cromatiche emozionali si fondono con il trasporto percepito nel momento in cui il suo sguardo si è posato su quei luoghi, evidenziandone i dettagli che lo hanno conquistato ma anche concedendo all’osservatore di ampliare la sua attenzione su tutto ciò che è circostante, che si trova intorno come se, allo stesso modo delle opere dedicate agli interni, ogni elemento della composizione fosse essenziale per amplificare la coralità finale.

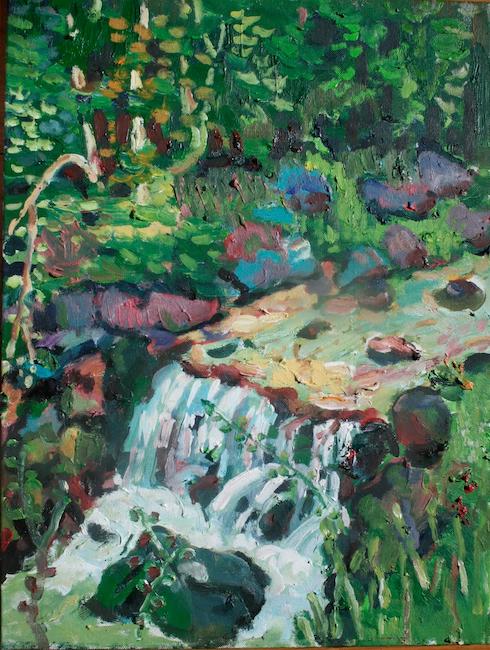

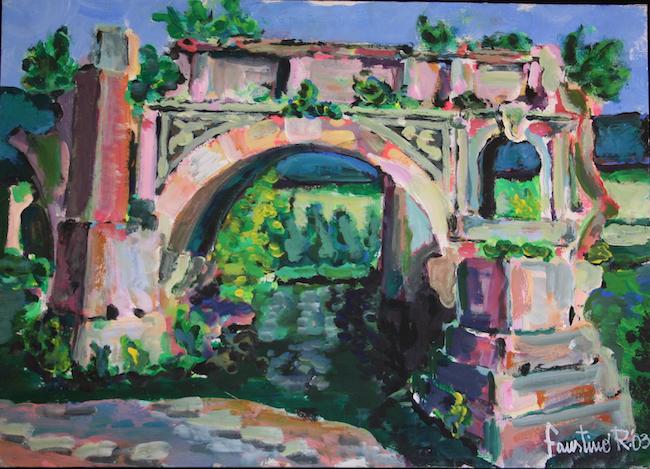

Questo concetto descrittivo si manifesta in particolar modo in Cascata da Ratzes, in cui i particolari della vegetazione intorno alla cascata sembrano confondersi con il corso d’acqua prima che compia il salto e i cui colori intensificano la chiarezza dell’acqua stessa, e in Ponte rotto 3 dove l’arco sembra essere entrato nel paesaggio, accolto dalla natura e inglobato all’interno di essa anche se di fatto appartiene all’opera dell’uomo in grado di generare qualcosa di grande senza perdere il rispetto per il mondo che lo accoglie, come avviene invece nella società contemporanea. Faustino Roncoroni, ex architetto ha deciso di dedicarsi solo alla sua carriera artistica, impartisce lezioni di disegno dal vero e prospettiva, ha al suo attivo molte mostre collettive in Italia e all’estero, diverse personali di cui due a Bruxelles e fa parte del gruppo artistico Scketchcrawl di Roma.

FAUSTINO RONCORONI-CONTATTI

Email: faustino.artista@gmail.com

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/faustino.roncoroni

Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/in/faustino-roncoroni-790b2586/

The secret and amusing life of untidy objects in Faustino Roncoroni’s Expressionism

The world of everyday objects has been subject of study and investigation for many artists in previous centuries, and in contemporary art it has taken the form of a tendency to emphasise everything that would otherwise be considered a simple tool of functional use and that instead transforms its essence thanks to the artist’s gaze. In the case of today’s protagonist, inanimate things almost take on an animated aspect, as if their presence in space constituted a way of showing themselves, of underlining their existence, of affirming a hidden and improbable personality capable of escaping from the artwork and communicating with the observer.

With the birth of Expressionism, between the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth, all the objects and places in which human beings moved began to become essential co-protagonists of the artworks, both because of their relevance to ordinary life and because of their ability to absorb the emotions and sensations emanating from the people portrayed or from the landscapes immortalised by the great protagonists of this artistic movement. Beginning with the experimentation and theories of the Fauves, who were the basis from which the guidelines of Expressionism were outlined, attention to the emotional simplicity of everything that surrounded human beings, including the reassurance provided by environments and everyday objects, became an integral part of the pictorial approach and the propagation of perceived sensations, the protagonists of the canvases of the major exponents of those early expressive revolutions, including Henri Matisse, Maurice De Vlamink and André Derain. Matisse’s detailed interiors, distinguished by saturated, intense colours, told of an attachment to all those things that belonged to his routine, or to that of his protagonists, and from which no one was able to disregard them precisely because they were linked to reassuring sensations, enveloping because of their constant presence, their being part of the passing of time, protagonists of almost automatic actions without which certainties would have been lost.

Whereas Matisse focused on the entire room, the details but also the rooms or corners in which the objects were contained, the other great exponent of the Fauves movement, Maurice De Vlamink, instead highlighted the individual object or composition, abstracting it from the background as if the latter were not fundamental but merely an indefinite base to focus the image in the foreground. When, on the other hand, he decided to widen his gaze to the totality of an enclosed space, a room or a bedroom, he could not help but introduce the human figure, underlining how much for him the object was linked to the user, as much as the emotion aroused and diffused towards objects could not be separated from the person feeling it. The artist from Lazio, Faustino Roncoroni, is strongly linked to Expressionism, and at times to the Fauves, both for his emotional tones, connected with the range of sensations that man feels and that everything around him reflects, and for the particularity of emphasising the things that fill everyone’s life, those products, those articles that are fundamental for allowing simple routine gestures to be carried out, for connecting to memories, and remaining tied to a habit that reassures. And yet in that apparent immobility the artist seems to imply the vitality of those objects, as if they had a life of their own within which they play at hiding, disappearing in order to be sought out, and this is precisely the sensation that Roncoroni arouses in the observer, that of having to let his gaze wander over the canvas to recognise those familiar details, to find that particular book, blanket, vase or glass in virtue of which he feels at home, as if that disorder of which the artist’s artworks speak corresponds at bottom to the confusion that often assails the human mind and that needs to get lost in the chaos before being able to put ideas in order and from there go on with greater awareness. Perspective, often non-existent in the guidelines of Expressionism, in Roncoroni’s painting is used to conceal and stack objects, thus requiring levels of depth within which to place and allow a glimpse of edges, details and particulars through which the artist guides the observer’s gaze to discover what goes beyond immediate appearance. The narrative has nothing romantic or poetic about it, as in the artworks of the masters of the twentieth century, but rather enters into the contemporary world, recounting everything that is part of modern life while emphasising the importance of culture, that filling the rooms observed with shelves full of books to induce the observer not to forget or neglect the importance of knowledge, be it of the present, of history or of any subject that needs to be explored. In Stanza di Roma (Roma’s room) painting, Faustino Roncoroni literally lets himself be fascinated, enveloped by everything he finds in front of his eyes, each element complementing the next as if one needed the other to exist, as if the presence of the computer screen were indivisible from that of the chair opposite, as if the mirror were functional to highlight everything that lies beneath.

The elements of the composition converse with each other, sending the observer an amused and amusing image that makes him feel involved precisely because of that confusion, that high-impact juxtaposition that all in all resembles most people’s workrooms, that orderly chaos in which everything can be found because it is akin to the personality and mental process of the owner of the objects. In Dopo il trasloco (After the moving) the artist recounts the sense of disorientation that one is forced to face following a move, a radical change in which objects are the only ones to constitute the certainties and to give the possibility of reconstructing an atmosphere that in the end does not belong to a place but to the emotional baggage, and it is in this that things are linked to sensations, that follows the human being wherever he chooses to live. The disorder described by Roncoroni corresponds to the emotional disorientation that each modification, each transformation, brings with it, despite the awareness, constituted by the rationality of the things possessed, that certain passages are necessary to move towards a new tomorrow. The tones are thus in tune with the enthusiasm of that new path, with the liveliness that inevitably envelops the moment just after the decision to break away from the past, with the warmth of the desire to reconstruct new securities and new reassurances, making use of what has been preserved from that past. When he comes out of the interior to describe landscapes and views Faustino Roncoroni lets himself be influenced by the intense style of André Derain but also by the suspended unreality of Maurice De Vlamink, creating a synthesis in which the emotional chromatic tones blend with the transport perceived at the moment when his gaze rests on those places, highlighting the details that captivated him, but also allowing the observer to broaden his attention to all that is around, as if, in the same way as in the artworks dedicated to interiors, each element of the composition were essential to amplify the final chorus. This descriptive concept is particularly evident in Cascata da Ratzes (Da Ratzes waterfall), in which the details of the vegetation around the waterfall seem to merge with the river before it makes its leap and whose colours intensify the clarity of the water itself, and in Ponte rotto 3 where the arch seems to have entered the landscape, welcomed by nature and incorporated within it even though it actually belongs to the work of man, capable of generating something great without losing respect for the world that welcomes it, as instead happens in contemporary society. Faustino Roncoroni, a former architect, has decided to devote himself solely to his artistic career. He gives lessons in life drawing and perspective, and has to his credit many group exhibitions in Italy and abroad, several personal exhibitions, including two in Brussels, and is a member of the Scketchcrawl art group in Rome.