Nel corso della storia dell’arte alcuni artisti hanno lasciato un segno nell’immaginario collettivo per la loro capacità di parlare un linguaggio semplice, elementare, facilmente comprensibile dall’adulto come dal bambino che spesso si nasconde all’interno di un’apparenza più matura; il vivere contemporaneo, le complicazioni dell’esistenza molto più articolata rispetto a quella dei secoli precedenti, hanno indotto i creativi ad affrontare temi consistenti, facendo emergere ferite e dolori, lasciando trapelare l’irruenza del proprio sentire interiore sulle tele. La protagonista di oggi recupera invece la precedente tendenza a mettere in luce la spontaneità fanciullesca, un mondo pieno di gioia proprio perché legato a quelle emozioni misurate e serene che sembrano appartenere ormai a tempi lontani.

Molto spesso un approccio eccessivamente semplice nello stile pittorico è stato guardato con distacco e diffidenza dagli ambienti artistici di fine Ottocento e del Novecento, perché l’arte doveva essere appannaggio degli intellettuali, di chi aveva una cultura adeguata a poter comprendere il messaggio di bellezza e di somma espressività che l’arte porta con sé. Tuttavia vi furono diverse correnti e, soprattutto, maestri del secolo scorso che vollero contrastare questo concetto e basarono tutta la loro produzione esattamente sul concetto di semplicità, di mantenimento di quello spirito fanciullesco in grado di trasportare l’osservatore in una dimensione di sogno, o fiaba oppure in mondi improbabili dove tutto poteva essere vissuto con lo stesso sguardo meravigliato e puro del bambino. I primi a voler dare rilevanza a questo tipo di approccio semplice e diretto furono gli artisti che aderirono al movimento Naif, uno fra tutti Henri Rousseau che con le sue riproduzioni immaginarie di mondi lontani, con l’approccio spontaneamente ingenuo alla tela fu osteggiato dai critici e dalle grandi gallerie della sua epoca ma apprezzato dagli artisti coevi fondatori di altre correnti; la trasposizione della realtà al mondo del sogno, del mito e dell’immaginario, completamente privi di apparato prospettico, furono i suoi tratti distintivi in virtù dei quali le sue opere furono apprezzate da un pubblico più vasto di quello ristretto dei salotti culturali. Marc Chagall, nel medesimo periodo, scelse di adottare uno stile differente e difficilmente classificabile, a metà tra Espressionismo e Cubismo, per narrare il suo mondo magico in cui i buoni sentimenti, le situazioni quotidiane e le emozioni serene e pacate costituivano il fulcro di un modo di intendere la vita molto vicino a quello del bambino che aveva mantenuto dentro di sé; tele come La passeggiata e Compleanno evocano la purezza del sentire in grado di elevare e di trasportare in una dimensione al di sopra del cielo, come in una bellissima favola da cui osservare il mondo sottostante e sorridere del benessere che la capacità di apprezzare le piccole cose sa infondere. Ma anche il Surrealismo con Joan Mirò ha avuto il suo esponente che si è distinto per la linearità del tratto e per le forme essenziali attraverso cui riusciva a esprimere il suo mondo onirico e incantato in modo diretto, basico eppure in grado di emozionare il pubblico adulto tanto quanto quello dei più giovani. Sulla scia di questo intento pittorico, di questa necessità interiore di restare legata alle emozioni più pure, primordiali, giocose perché appartenenti a memorie di istanti quotidiani piacevoli e felici, si delinea l’estro creativo dell’artista abruzzese Raspu Paola, la quale pur scegliendo uno stile Espressionista, lo personalizza traslandolo verso la dimensione fantastica, incantata che però non riesce a distaccarsi completamente dalla realtà osservata.

Lo sguardo della Raspu diviene filtro per permettere all’osservatore di astrarsi da una contingenza che spesso sembra non avere più niente di piacevole né motivi per sorridere, e di ritornare al contatto con la parte più semplice di sé, quella che gli consente di evidenziare quanta bellezza e letizia si nasconde dentro le pieghe della quotidianità; l’artista racconta di momenti conviviali, ordinari eppure straordinari proprio in virtù delle sensazioni di leggerezza e di tranquillità che rilasciano non solo nelle sensazioni dell’autrice delle tele bensì anche di chi osserva e si ritrova trasportato nella dimensione della favola.

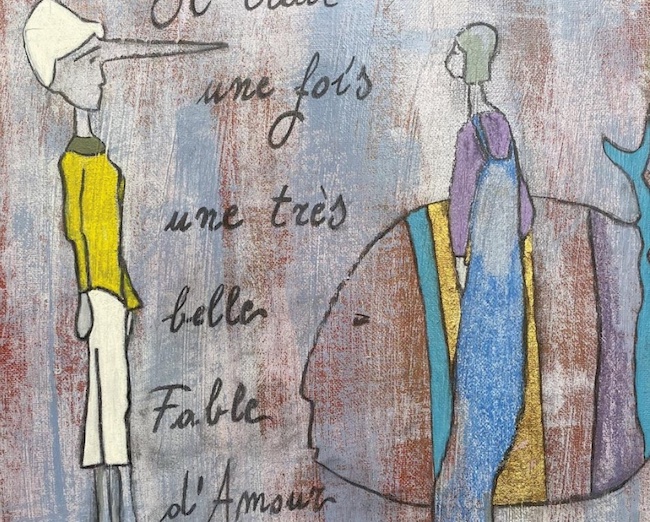

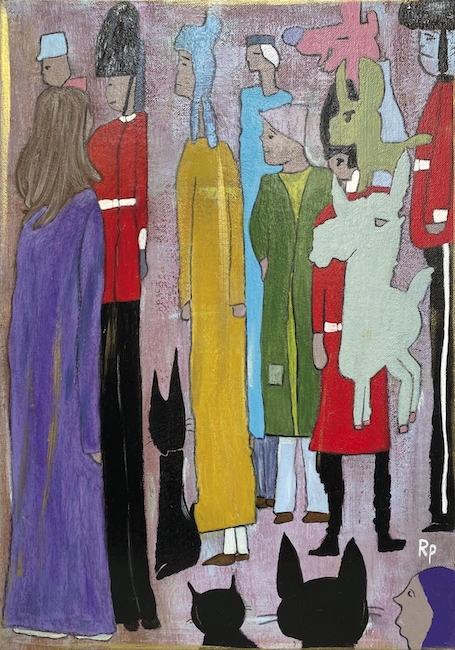

I personaggi reali si alternano a quelli fantastici appartenenti all’immaginario comune, come nella tela Cupido in cui il folletto dell’amore sembra assistere alla scena indeciso su chi puntare la sua freccia fatale, o forse semplicemente si sta guardando intorno per proteggerlo quel sentimento appena nato; la narrazione della Raspu è lineare, ha il sapore delle feste in casa organizzate per far conoscere gli amici single, di quelle in cui nascevano gli amori più duraturi perché chi decideva di combinare gli incontri la sapeva lunga su cosa è necessario affinché due persone restino insieme. La figura mitica è inserita nell’ambiente circostante come se la sua presenza fosse naturale, come se la fantasia si mescolasse con la realtà per generare una dimensione intermedia in cui tutto è possibile.

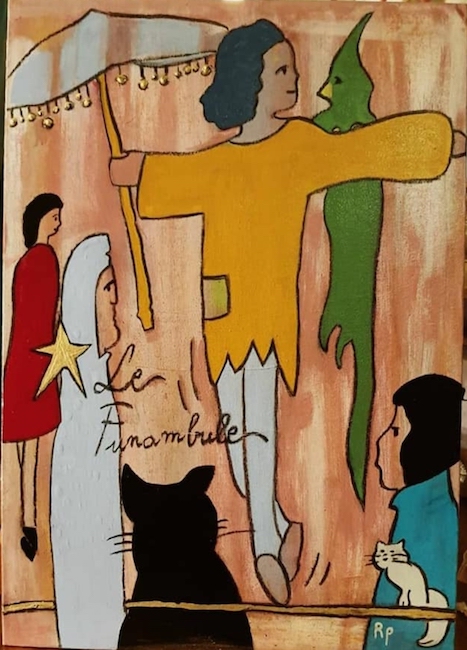

In Le Funambule l’artista racconta un’atmosfera bohemienne, un’ambientazione nostalgica di un’epoca in cui gli artisti di strada si esibivano per strabiliare i passanti, per esibire le loro capacità e solo al termine della dimostrazione del loro talento lasciavano scegliere a chi aveva osservato se donare un piccolo obolo; la prospettiva è completamente sovrapposta, quasi come se il funambolo si trovasse in mezzo alle persone che lo osservano, non sopra come sarebbe naturale, e volesse coinvolgerle nel suo gioco. La gioia che si percepisce nel protagonista della tela è quella di chi ha scelto di fare ciò che ama di più, senza regole, senza gabbie, senza formalità, ed è proprio questo che sembra colpire tutto il mondo intorno a lui, che sia costituito di persone sensibili in grado di andare oltre il visibile o di animali che si affidano costantemente al proprio intuito, all’istinto che permette loro di distinguere ciò che è buono da ciò che non lo è. Il tratto espressionista è evidente sia nei netti contorni ma anche nel colore steso in maniera uniforme e netta, senza chiaroscuro e senza affidarsi alla terza dimensione per definire il suo approccio nostalgico.

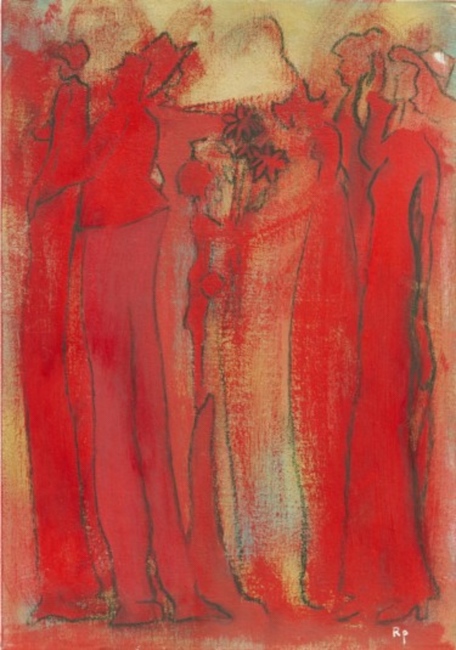

Allo stesso modo nelle opere in cui Raspu Paola decide di abbandonare la visione della realtà e spostarsi verso la memoria sognante o, per meglio dire, la fantasia di un istante che può essere accaduto o esistere solo nella mente dell’artista, viene meno anche la necessità di ampliare la gamma cromatica e di delineare con nitidezza i bordi, le sagome, che divengono così figure idealizzate appartenenti a una terra di mezzo tra ciò che esiste davvero e ciò che è solo un desiderio, una dimensione ideale; l’opera Il regalo dal mare rappresenta esattamente questo concetto, quel lasciare all’osservatore il sapore morbido della fantasia tra il mitologico e il fantastico, un’ambientazione ideale in cui i sentimenti sono puri e limpidi come l’acqua e quel dono di cui accenna nel titolo è la vita, rappresentata da un neonato giunto a illuminare di luce i protagonisti adulti, i genitori.

Si muove sul filo sottile tra gioco e sorridente ironia Raspu Paola che manifesta la sua creatività con spontaneità, con la gioia di restituire immagini positive, serene, di frangenti della sua vita familiare oppure semplicemente osservati da tutto ciò che le ruota intorno. Nel corso della sua carriera Raspu ha partecipato a numerose e importanti mostre collettive a Roma, Perugia, Chieti, e una personale alla Fortezza di Civitella del Tronto, ha ricevuto un premio della critica da Irdidestinazionearte presso il Museo Ugo Guidi di Forte dei Marmi ed è stata selezionata e inserita nell’edizione dell’anno 2021 dell’Atlante dell’Arte Contemporanea De Agostini.

RASPU PAOLA-CONTATTI

Email: raspupaola@yahoo.com

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/paola.raspu

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/raspu.paola/

The simplicity and joy of a fairytale world in Raspu Paola’s artworks

Throughout the history of art, some artists have left their mark on the collective imagination for their ability to speak a simple, elementary language, easily understood by adults as well as by children, who often hide within a more mature appearance. Contemporary life, the complications of a much more articulated existence compared to that of previous centuries, have led artists to deal with substantial themes, bringing out wounds and pain, letting the impetuousness of their inner feelings seep out onto their canvases. Today’s protagonist, on the other hand, recovers the previous tendency to highlight childlike spontaneity, a world full of joy precisely because it is linked to those measured and serene emotions that now seem to belong to distant times.

Very often, an excessively simple approach to painting was viewed with detachment and distrust by the artistic circles of the late 19th and 20th centuries, because art was supposed to be the prerogative of intellectuals, of those who had an adequate culture to be able to understand the message of beauty and supreme expressiveness that art brings. However, there were various currents and, above all, masters of the last century who wanted to oppose this concept and based their entire production precisely on the concept of simplicity, of maintaining that childlike spirit capable of transporting the observer into a dreamy dimension, or a fairy tale, or into improbable worlds where everything could be experienced with the same amazed and pure gaze of a child. The first to give importance to this type of simple and direct approach were the artists who adhered to the Naïve movement, one of whom was Henri Rousseau, whose imaginary reproductions of distant worlds and spontaneously naïve approach to the canvas were opposed by the critics and the great galleries of his time but appreciated by the contemporary artists who founded other currents; the transposition of reality into the world of dreams, myth and the imaginary, completely devoid of any perspective apparatus, were his distinctive traits, thanks to which his works were appreciated by a broader public than the narrow cultural salons. Marc Chagall, in the same period, choosed a different style, difficult to classify, halfway between Expressionism and Cubism, to narrate his magical world in which good feelings, everyday situations and calm emotions were at the heart of a way of understanding life very close to that of the child he had kept within himself; Canvases such as La passeggiata (The Walk) and Compleanno (Birthday) evoke the purity of feeling capable of elevating and transporting to a dimension above the sky, as in a beautiful fairytale from which to observe the world below and smile at the well-being that the ability to appreciate small things can instil. But Surrealism with Joan Mirò also had an exponent who stood out for the linearity of his strokes and the essential forms through which he was able to express his dreamlike and enchanted world in a direct, basic way that was nevertheless able to excite the adult public as much as the younger ones.

In the wake of this pictorial intent, of this inner need to remain tied to the purest, most primordial, playful emotions because they belong to memories of pleasant, happy everyday moments, is outlined the creative flair of the Abruzzese artist Raspu Paola who, although choosing an Expressionist style, she personalises it by shifting it towards a fantastic, enchanted dimension which, however, is unable to detach itself completely from the observed reality. Raspu’s gaze becomes a filter that allows the observer to withdraw from a contingency that often seems to have nothing pleasant and no reason to smile, and to return to contact with the simplest part of himself, the part that allows him to highlight how much beauty and joy is hidden within the folds of everyday life; The artist tells of convivial, ordinary yet extraordinary moments precisely because of the sensations of lightness and tranquillity that they release not only in the feelings of the author of the paintings but also in those who observe them and find themselves transported into the dimension of the fairytale. The real characters alternate with the fantastic ones belonging to the common imagination, as in the painting Cupid in which the elf of love seems to be watching the scene, undecided on whom to aim his fatal arrow, or perhaps he is simply looking around to protect his new-born feeling; Raspu’s narration is linear, it has the flavour of the house parties organised to introduce single friends, of those in which the most lasting loves were born because those who decided to arrange the meetings knew a lot about what was necessary for two people to be together. The mythical figure is inserted into its surroundings as if its presence were natural, as if fantasy blended with reality to generate an intermediate dimension in which anything is possible.

In Le Funambule, the artist recounts a bohemian atmosphere, a nostalgic setting of a time when street artists used to perform to amaze passers-by, to show off their skills and only at the end of the demonstration of their talent did they let the onlookers choose whether to donate a small obolus; the perspective is completely superimposed, almost as if the tightrope walker were in the midst of the people watching him, not above as would be natural, and wanted to involve them in his game. The joy perceived in the protagonist of the canvas is that of someone who has chosen to do what he loves best, without rules, without cages, without formality, and it is precisely this that seems to affect the whole world around him, whether it is made up of sensitive people capable of going beyond the visible or animals who constantly rely on their intuition, on the instinct that allows them to distinguish what is good from what is not. The expressionist trait is evident both in the clear contours but also in the colour spread evenly and sharply, without chiaroscuro and without relying on the third dimension to define his nostalgic approach. In the same way, in the artworks in which Raspu Paola decides to abandon the vision of reality and move towards the dreaming memory or, to put it better, the fantasy of an instant that may have happened or exist only in the artist’s mind, the need to widen the chromatic range and sharply delineate the edges, the silhouettes, is also reduced. They thus become idealised figures belonging to a middle ground between what really exists and what is only a desire, an ideal dimension; The painting Il regalo dal mare (The gift from the sea) represents exactly this concept, leaving the observer with the soft taste of fantasy between mythology and fantasy, an ideal setting in which feelings are pure and limpid like water and the gift mentioned in the title is life, represented by a newborn baby who has come to illuminate the adult protagonists, the parents, with light. Raspu Paola moves along a fine line between playfulness and smiling irony, manifesting her creativity with spontaneity, with the joy of portraying positive, serene images of moments in her family life or simply observed from all that revolves around her. Over the course of her career, Raspu has taken part in numerous important group exhibitions in Rome, Perugia, Chieti, and a solo exhibition at the Fortezza di Civitella del Tronto. She received a critics’ prize from Irdidestinazionearte at the Museo Ugo Guidi in Forte dei Marmi and was selected and included in the 2021 edition of the Atlante dell’Arte Contemporanea De Agostini.