La rappresentazione della contingenza, dei paesaggi o dei protagonisti di un’opera si legano indissolubilmente allo stato d’animo, all’approccio alla vita contemporanea e al sentire filosofico di ciascun artista, divenendo così mezzo per narrare un punto di vista unico, personale, a volte intimo; in questa molteplicità di visioni, di modi di esprimersi, qualcuno si orienta verso una narrazione perfettamente attinente all’osservato, alla riproduzione, se pur arricchita di emozioni, di ciò che l’occhio coglie intorno a sé. Altri invece si pongono in una dimensione di ascolto dell’interiorità immaginando tutto ciò che si nasconde oltre lo sguardo, intuendo il legame sottile che lega indissolubilmente l’anima dell’essere umano alla parte più spirituale del visibile. L’artista di cui vi racconterò oggi è stata costantemente attratta da quell’interregno a metà tra ciò che è reale e tangibile e ciò che invece appartiene alla sfera dell’utopico, dell’illusione dentro cui rifugiarsi per manifestare le sensazioni più intime.

L’arte del Diciannovesimo fu contraddistinta da un ancora forte legame con i canoni estetici ed esecutivi accademici in cui la figurazione era necessaria all’artista per produrre un’opera, malgrado all’interno delle varie correnti che si avvicendarono in quel periodo cominciassero a emergere differenze espressive e soprattutto di intento creativo che le rendevano profondamente differenti. Dunque mentre il Romanticismo tendeva verso l’infinito, verso l’illimitato che spesso veniva identificato con la natura e tutti i suoi fenomeni che però generavano nell’uomo un senso di terrore e di impotenza ampiamente e variamente narrati dai romantici inglesi John Constable e William Turner, il Simbolismo andava invece a scavare nei significati profondi e sottili nascosti nella realtà trasformando l’opera d’arte nell’espressione dell’io, della spiritualità dell’esecutore dell’opera proiettando nell’oggetto il sentire del soggetto; e infine il Realismo si proponeva di cogliere ogni aspetto della realtà osservata raccontando l’immagine esattamente come percepita dall’occhio, senza influire personalmente su di essa bensì semplicemente mettendone in risalto la perfezione esecutiva e la fedeltà ai paesaggi, ai gesti e alle situazioni vissute dai personaggi immortalati dando una fotografia dell’epoca con particolare attenzione alle condizioni di vita della parte di popolazione meno abbiente. Successivamente a queste correnti artistiche il mondo dell’arte cominciò a essere scosso da profondi cambiamenti, a cominciare dall’Espressionismo che rivoluzionò ogni schema coloristico, prospettico ed esecutivo precedente per poi andare verso tutte quelle radicali modificazioni di inizio Novecento in cui tutte le regole accademiche furono sovvertite. Tuttavia vi furono artisti che vollero continuare a mantenersi legati allo stile figurativo pur oltrepassando le singole regole dei movimenti dell’Ottocento, in alcuni casi distaccandosene completamente ed estremizzandone le linee guida come nel caso dell’Iperrealismo che ebbe i maggiori rappresentanti negli Stati Uniti, in altri invece mescolando abilmente le tematiche principali fino a giungere a uno stile in cui interiorità, spiritualità e realtà sono in perfetto equilibrio e riescono a infondere nell’osservatore sensazioni avvolgenti e di incredibile familiarità. È stato questo il caso di Gabriella Atanasi, in arte Gata, artista umbra prematuramente scomparsa nel 2020, le cui opere costituiscono un ponte tra il visibile e l’immaginato, tra la concretezza di tutto ciò che appare davanti agli occhi e la pulsione emozionale in cui l’interiorità lo trasforma, passando dalla nostalgia del ricordo all’aspettativa del desiderato o più semplicemente all’equilibrio, appartenente all’essere umano, tra l’intimità di un pensiero, di una speranza, di una sensazione e il circostante che quella sensazione suscita.

Le protagoniste, sempre donne quasi come se fossero un alter ego dell’artista oppure un modo per dar voce a quel femmineo che troppo spesso viene trascurato nella sua complessa fragilità, si lasciano andare al loro mondo emozionale, colte dalla Atanasi nelle loro espressioni più inconsapevoli, più intimiste, raccolte in riflessione su ciò che è stato e su ciò che potrebbe verificarsi se le loro aspettative si trasformassero in realtà.

La dimensione del sogno, quell’interregno in cui diviene necessario rifugiarsi per cercare una fuga dalla realtà, un luogo in cui trovare il contatto con se stesse, conduce così verso un avvicinamento alla Metafisica, in cui l’osservato perde il suo senso contingente e ne trova un altro in cui gli oggetti si decontestualizzano o, per meglio dire, trovano un’identità diversa che permette loro di infondere nell’opera quel senso di mistero, di enigma interrogativo sull’interazione tra il profondo sentire e tutto ciò che circonda il soggetto.

L’opera Realtà ambivalenti è emblematica di questo concetto in virtù del suo confondere l’ambiente in cui è collocata la protagonista, di spalle rispetto all’osservatore, e un oggetto osservato, un quadro nel quadro, che sembra rappresentare una realtà più viva e intensa, in grado di catturare lo sguardo della donna al punto di indurla a immaginare che i dettagli entrino nella stanza dalla quale sta guardando; emerge un bisogno di protezione della ragazza per la quale l’interno costituisce un guscio in cui si sente sicura, pur non potendo fare a meno di desiderare di essere capace di uscire da quella corazza e scoprire tutto ciò che la vita reale offre. Le due forze sembrano essere opposte e il risultato è il senso di incertezza, di immobilità che non le permette di fare quel passo in più che la renderebbe protagonista scegliendo così di restare spettatrice; o forse al contrario, Gata la ritrae nel momento prima che la decisione di agire venga presa e il cambiamento venga attuato.

Anche in Risveglio si conferma la vicinanza con la Metafisica poiché la protagonista sembra volersi allontanare da un mondo omologato, da regole e schemi che rendono l’individuo simile ai manichini che l’artista pone nello sfondo, simbolo di un vivere contemporaneo troppo alienante e distaccato dalle naturali inclinazioni interiori; nel distacco la donna in primo piano trova se stessa, i suoi veri colori, la sua purezza, la sensibilità profonda che non riesce a uniformarsi alla freddezza e alle condizioni implicite nella generalizzazione verso cui il mondo vorrebbe condurla.

Nella tela La realtà del sogno è nuovamente messa in evidenza la distanza tra immaginario e contingenza che però non può fare a meno di avvolgere e coinvolgere le sensazioni percepite, respirate dalla donna al punto di non riuscire a farle uscire dalla propria mente e dalla propria interiorità; così l’osservato si confonde con il ricordo, con un visibile che disorienta poiché impossibile stabilire se sia qualcosa di effettivamente davanti allo sguardo oppure prodotto dal sogno nostalgico della protagonista. L’abilità di Gabriella Atanasi è quella di condurre l’osservatore nel suo mondo emozionale per poi destabilizzarlo attraverso l’illusione che tutto ciò vedono i suoi occhi non sia effettivamente lì, come nel caso dell’immagine della casa immersa tra le colline che a tratti sembra essere una cartolina, un frammento di memoria della ragazza in primo piano.

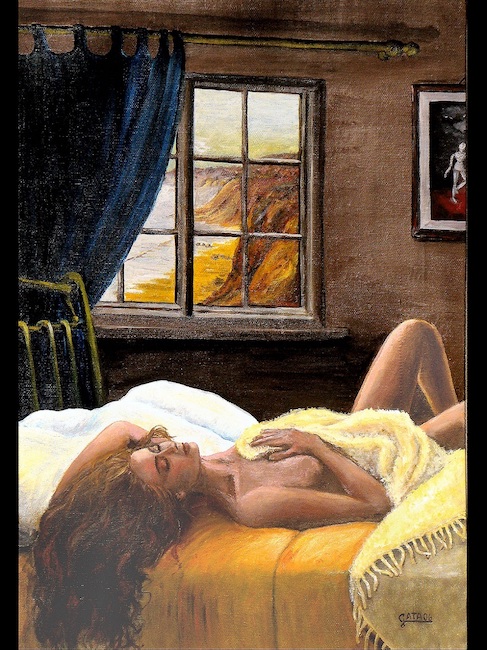

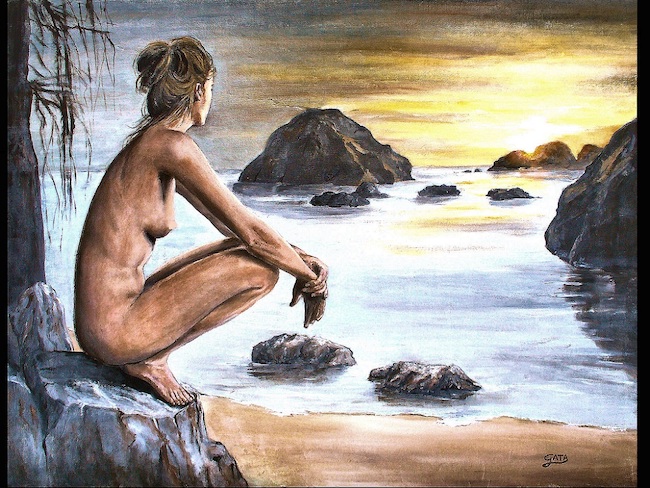

Poi vi sono le opere più realiste, intimiste, in cui emerge un Simbolismo che non cerca nulla al di fuori dell’individuo bensì lo induce a ripiegarsi su se stesso, a interrogarsi sul proprio percorso e sulla personale evoluzione; a questa serie di tele appartiene Prima di conoscere in cui la nudità della protagonista rappresenta la tela bianca antecedente il successivo cammino di approfondimento e di scoperta della reale essenza, quella che può fuoriuscire ed essere svelata solo a seguito delle esperienze, delle circostanze che, nel bene e nel male, contribuiscono a costruire le complesse sfaccettature della personalità.

Nel corso della sua lunga carriera artistica Gata, formatasi frequentando corsi di maestri di rilevanza nazionale, ha frequentato la comunità di Carmel by the Sea di San Francisco, acquisendo alcune delle tecniche e caratteristiche stilistiche del gruppo che le hanno permesso di ampliare e personalizzare il suo linguaggio pittorico; le sue opere sono presenti in collezioni private in Italia, Francia, Austria, Germania, Gran Bretagna, Messico e Stati Uniti.

GABRIELLA ATANASI-CONTATTI

Email: gatanasi@gmail.com

sergioserani@gmail.com

The middle ground between dream and reality in the Realist artworks of Gabriella Atanasi

The representation of the contingency, the landscapes or the protagonists of an artwork are inextricably linked to the state of mind, the approach to contemporary life and the philosophical feelings of each artist, thus becoming a means of narrating a unique, personal, sometimes intimate point of view. In this multiplicity of visions and ways of expressing oneself, some tend towards a narration perfectly pertinent to the observed, to the reproduction, albeit enriched with emotions, of what the eye catches around it. Others, on the other hand, place themselves in a dimension of listening to interiority, imagining all that is hidden beyond the gaze, intuiting the subtle link that indissolubly binds the soul of the human being to the most spiritual part of the visible. The artist I am going to tell you about today was constantly attracted by that interregnum halfway between what is real and tangible and what belongs to the sphere of the utopian, of illusion in which to take refuge in order to manifest the most intimate feelings.

Nineteenth-century art was still marked by a strong bond with the aesthetic and executive academic canons in which figuration was necessary for the artist to produce an artwork, despite the fact that within the various currents that followed one another in that period, differences in expression and above all began to emerge in creative intent that made them profoundly different. Thus, while Romanticism tended towards the infinite, towards the limitless, which was often identified with nature and all its phenomena that, however, generated in man a sense of terror and impotence widely and variously narrated by the English Romantics John Constable and William Turner, Symbolism, on the other hand, delved into the deep and subtle meanings hidden in reality, transforming the artwork into an expression of the ego, of the spirituality of the work’s creator, projecting the subject’s feelings onto the object; and finally Realism aimed to capture every aspect of the reality observed by telling the image exactly as perceived by the eye, without personally influencing it but simply highlighting the perfection of the execution and the fidelity to the landscapes, gestures and situations experienced by the characters immortalised by giving a photograph of the time with particular attention to the living conditions of the less wealthy population. After these artistic currents, the art world began to be shaken by profound changes, starting with Expressionism, which revolutionised every previous colouristic, perspective and executive scheme, and then moving on to all those radical changes of the early 20th century in which all academic rules were subverted. However, there were artists who wanted to continue to be linked to the figurative style while going beyond the individual rules of the 19th century movements, in some cases completely detaching themselves from it and taking its guidelines to extremes, as in the case of Hyperrealism, which had its greatest representatives in the United States, while in others they skilfully mixed the main themes until reaching a style in which interiority, spirituality and reality are in perfect balance and succeed in instilling in the observer enveloping sensations of incredible familiarity.

This was the case of Gabriella Atanasi, known as Gata, an Umbrian artist who died prematurely in 2020, whose artworks form a bridge between the visible and the imagined, between the concreteness of everything that appears before the eyes and the emotional impulse into which interiority transforms it, passing from the nostalgia of memory to the expectation of the desired or, more simply, to the balance, belonging to the human being, between the intimacy of a thought, of a hope, of a sensation and the surroundings that those sensation arouses. The protagonists, always women, almost as if they were an alter ego of the artist or a way to give voice to that feminine side which is too often neglected in its complex fragility, let themselves go to their emotional world, caught by Atanasi in their most unconscious, most intimate expressions, gathered in reflection on what has been and what could happen if their expectations were transformed into reality. The dimension of the dream, that interregnum in which it becomes necessary to take refuge in order to seek an escape from reality, a place in which to find contact with oneself, thus leads towards a rapprochement with Metaphysics, in which the observed loses its contingent sense and finds another in which the objects are decontextualised or, rather, find a different identity that allows them to instil in the artwork that sense of mystery, of enigma questioning the interaction between deep feeling and everything that surrounds the subject. The painting Realtà ambivalenti (Ambivalent Realities) is emblematic of this concept by virtue of its confusion between the setting in which the protagonist is placed, with her back to the observer, and an observed object, a painting within a painting, which seems to represent a more vivid and intense reality, capable of capturing the woman’s gaze to the point of leading her to imagine that the details enter the room from which she is looking; there emerges a need for protection in the girl, for whom the interior constitutes a shell in which she feels safe, although she cannot help wishing she were able to get out of that shell and discover all that real life has to offer.

The two forces seem to be opposed and the result is a sense of uncertainty, of immobility that does not allow her to take that extra step that would make her a protagonist, thus choosing to remain a spectator; or perhaps on the contrary, Gata portrays her in the moment before the decision to act is taken and the change is implemented. In Risveglio (Awakening), too, is confirmed the proximity to Metaphysical Art, as the protagonist seems to want to distance herself from a standardised world, from the rules and schemes that make the individual similar to the mannequins the artist places in the background, the symbol of a contemporary way of life that is too alienating and detached from natural inner inclinations; in detachment, the woman in the foreground finds herself, her true colours, her purity, the profound sensitivity that is unable to conform to the coldness and conditions implicit in the generalisation towards which the world would like to lead her. In the painting La realtà del sogno (The Reality of the Dream), the distance between the imaginary and the contingency is once again highlighted, but it cannot fail to envelop and involve the sensations perceived and breathed in by the woman to the point that she is unable to get them out of her mind and her interiority; thus the observed is confused with the memory, with a visible that is disorienting because it is impossible to establish whether it is something actually before the eyes or something produced by the protagonist’s nostalgic dream. Gabriella Atanasi’s skill is to lead the observer into her emotional world and then destabilise him through the illusion that whatever his eyes see is not actually there, as in the case of the image of the house surrounded by hills which at times seems to be a postcard, a fragment of the girl’s memory in the foreground.

Then there are the more realistic, intimist artworks, in which a Symbolism emerges that seeks nothing outside the individual but induces him to withdraw into himself, to question his own path and personal evolution; to this series of canvases belongs Prima di conoscere (Before knowing), in which the nudity of the protagonist represents the blank canvas preceding the subsequent path of in-depth study and discovery of her real essence, which can only emerge and be revealed as a result of the experiences and circumstances that, for better or worse, contribute to building the complex facets of her personality. In the course of her long artistic career, Gata, trained by attending courses held by nationally renowned masters, has frequented the Carmel by the Sea community in San Francisco, acquiring some of the group’s techniques and stylistic characteristics that have enabled her to broaden and personalise her pictorial language; her artworks are present in private collections in Italy, France, Austria, Germany, Great Britain, Mexico and the United States.