Il mondo moderno rincorre costantemente modelli di bellezza, canoni estetici, troppo spesso irraggiungibili che hanno dunque la conseguenza di far sentire inadeguato l’individuo, come se il non corrispondere a quell’ideale comporti l’esclusione dalla società, l’emarginazione dovuta a un approccio eccessivamente superficiale all’esistenza che sembra però dettarne le regole. Esistono tuttavia nella contemporaneità artisti che desiderano sottolineare quanto il non rientrare all’interno di quelle rigide linee guida esteriori generi un senso di libertà e di sicurezza in se stessi che rende l’individuo spogliato da convenzioni e felice di essere se stesso, di restare nella propria pelle. L’artista di cui vi racconterò oggi esalta la tendenza ad andare contro gli schemi e, proprio per questo, ad assaporare la vita in tutte le sue sfumature, anche le più rotonde.

Dopo molti secoli in cui l’arte aveva esaltato la bellezza riproducendo i modelli estetici del periodo storico a cui gli artisti appartenevano, si è generato nel Novecento un corto circuito, quello che di fatto ha sovvertito le regole e messo in discussione tutti i punti fermi delle linee guida accademiche, durante il quale si è verificata una ribellione nei confronti dell’armonia estetica così come classicamente intesa, perché il corpo umano doveva diventare un’emanazione dell’interiorità, una connessione tra sentire ed essere a prescindere che la sua forma visibile fosse o meno piacevole. Agli inizi del Ventesimo secolo fu l’Espressionismo ad aprire le porte alla distorsione delle forme per prediligere l’espressività che spesso doveva allontanarsi dalla perfezione, dall’equilibrio che aveva contraddistinto i secoli precedenti, per allinearsi con quelle profondità emozionali spesso destabilizzanti; e il corpo umano inteso come narrazione di quelle inquietudini, sfocianti a volte in atteggiamenti estremi e dissoluti a coprire la voce delle angosce, fu protagonista della pittura di Egon Schiele. Qualche anno dopo il tema fu ripreso e ampliato da un grande esponente della Scuola di Londra, Lucian Freud che con le sue figure nude e corpulente voleva evidenziare la debolezza della carne intesa sia dal punto di vista sessuale che da quello della fragilità umana; ciò che emerge dalle sue opere di grandi dimensioni è l’insicurezza, la timidezza generata dalla coscienza di non appartenere alla parte bella della società, quella più patinata, elegante, sobria, eppure i suoi personaggi sfidano quasi quelle convenzioni, si mostrano per come sono, nella loro nudità che rappresenta il loro modo di essere. Parallelamente all’interiorizzazione compiuta da questi due grandi maestri, vi fu il lavoro di un altro mostro sacro dell’arte del Novecento, il colombiano Fernando Botero il quale con la semplicità e la spontaneità di uno stile immediato e facilmente fruibile, il Naif, scelse di esaltare il mondo rotondo, quello di persone che rifiutano di farsi dettare le regole dall’esterno e vivono il loro peso in maniera serena, appagante, quasi lasciando intendere all’osservatore che la loro vita sia forse più felice perché priva di quel frustrante inseguimento di un modello troppo spesso irraggiungibile.

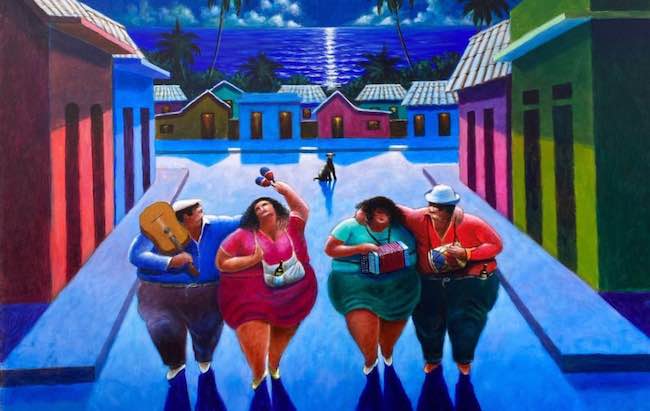

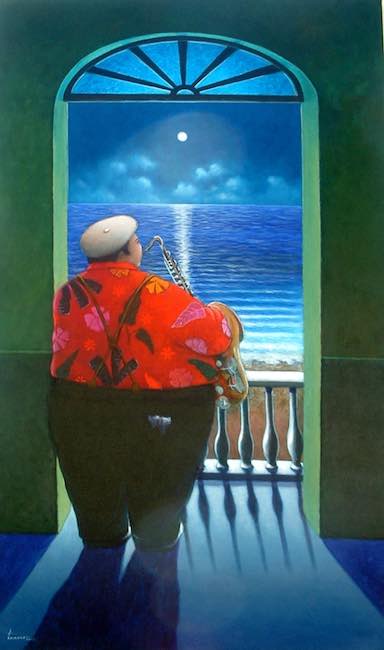

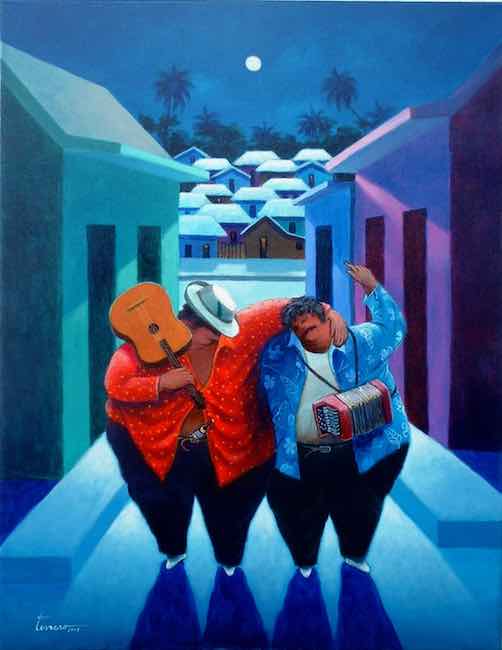

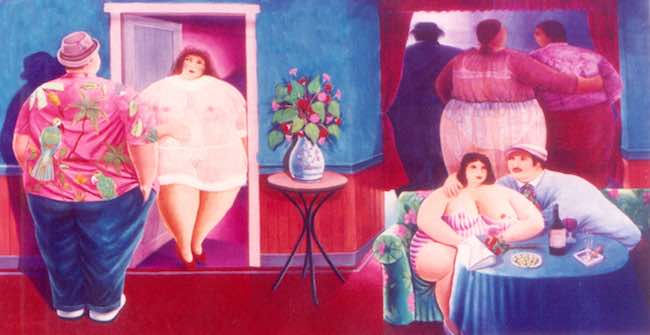

Laddove il peso è raccontato da Botero in modo sognante, ambientato in atmosfere reali ma quasi parte di una fiaba moderna, riadattando al suo punto di vista scene di vita quotidiana in cui tutto è visto in modo extralarge senza però perdere grazia, delicatezza e fascino, per l’artista dominicano Melchor Terrero invece la rotondità assume la connotazione di musicalità, di gioia che contraddistingue i popoli caraibici e che fuoriesce dai suoi scenari coinvolgenti e colorati proprio in virtù della loro immediatezza narrativa, di quell’essere su una linea a metà tra quotidianità tropicale e sogno di un mondo migliore, spensierato, in cui la capacità di assaporare ogni singolo istante prevale su tutto ciò che domina invece la cultura occidentale fatta di complicazioni, fretta, arrivismo che pur dando l’illusione di una felicità tende al contrario a generare frustrazioni, competitività e inappagamento. Ciò su cui si sofferma l’attenzione di Terrero, sono le immagini più tipiche del suo meraviglioso e colorato paese, i frammenti di lavoro quotidiano nei campi oppure la civetteria delle sue donne che non si curano di un peso eccessivo anzi, portano con orgoglio quelle rotondità che le fanno sentire affascinanti, sicure di sé, sottolineando come i canoni della bellezza siano differenti di paese in paese, di cultura in cultura. Melchor Terrero osserva i suoi personaggi nella loro essenza, in quell’attitudine a ricercare la felicità nelle piccole cose, il senso di appagamento in quei gesti semplici e ripetitivi che in fondo costituiscono la base stessa dell’esistenza, per poi, una volta terminato il dovere, lasciarsi andare al piacere, al divertimento, alla festa come gli abitanti della meravigliosa isola di Santo Domingo sanno fare.

Lo stile Naif latinoamericano è contraddistinto da una gamma cromatica vivace, intensa, variopinta esattamente come lo sono i palazzi, gli abiti, i contrasti tra cielo e mare in cui il popolo di quell’angolo di mondo è abituato a vivere, pertanto l’arte non può distaccarsi da quella che è la loro realtà quotidiana, la loro natura e Melchor Terrero sceglie a sua volta tonalità affini alla leggerezza del vivere felice, del superare ogni difficoltà con un sorriso, un momento di festa con gli amici per poi tornare a svolgere il proprio compito quotidiano. Dunque in lui il sovrappeso, la rotondità, divengono celebrazioni dell’interiorità, elevazione da un modello esteriore troppo spesso irraggiungibile per spingersi verso la vita vera, quella dell’imperfezione, della capacità di sentirsi a proprio agio nelle proprie nelle proprie vesti, a prescindere da quale taglia si abbia.

L’opera Pasarela (Passerella) ironizza sulla legge della moda che vuole far sfilare ragazze magrissime, mostrando all’osservatore quanto invece una donna di un peso più consistente possa in ogni caso apparire affascinante, seducente, sicura di sé anche stando sotto quei riflettori da cui, se si lasciasse intimorire dalla visione comune, dovrebbe sentirsi intimidita. La protagonista al contrario indossa un colore vivace ed è orgogliosa di avere addosso gli sguardi di un pubblico entusiasta e ammirato, composto da persone rotonde tanto quanto lei, quasi come se Terrero volesse mostrare all’osservatore un’altra possibilità, una realtà in cui potrebbero essere i magri a sembrare strani, come se la giovialità corrispondesse alla chiave di una felicità diversa.

La serie Recoletoras de flores (Raccoglitrici di fiori) racconta del momento del lavoro, di quella fatica quotidiana che permette però alle donne protagoniste di tornare a casa soddisfatte per aver svolto il loro compito, quello grazie al quale possono sfamare i loro bambini, sostenere i loro compagni e mariti nell’economia domestica; è un mondo di valori quello di Melchor Terrero, una dimensione in cui ciò che conta è l’interiorità, i buoni sentimenti, la sostanza che sovrasta l’apparenza sebbene anche in quelle grandi dimensioni, in quelle forme rotonde, si possa trovare una bellezza inaspettata se si è capaci di andare oltre tutto ciò che le convenzioni sociali impongono, quell’ideale i cui parametri sono stati definiti arbitrariamente e basandosi sulla superficialità dell’immagine, senza andare considerare l’interiorità, perché in fondo, sembra dire l’artista, la felicità è molto più raggiungibile e a portata di mano di quanto venga raccontato.

Ed è attraverso la convivialità, i momenti di condivisione dopo aver svolto il proprio lavoro che è possibile assaporare piccoli frangenti di spensieratezza e di gioia, raccontati da Melchor Terrero attraverso una delle sue serie più coinvolgenti, Musica y Ron, di cui fanno parte sia la sognante tela Serenata che la Noche de parranda (Notte fuori casa) in cui interpreta le sensazioni percepite durante una notte di divertimento, di leggerezza, di allontanamento della quotidianità per entrare nel mondo della musica, sempre presente nelle zone caraibiche, e in quello dell’allegria, della piacevolezza del vivere ballando e assaporando i momenti belli per portarli con sé nei giorni successivi. Il messaggio delle opere di Terrero è di indipendenza, libertà dalle regole e dai canoni tradizionali, suggerendo che forse è proprio ipotizzando il mondo al contrario, quello in cui i modelli imposti decadono e in cui la rotondità significa abbondanza di emozioni, di sensazioni e di naturalezza, che si nasconde la chiave della vera felicità.

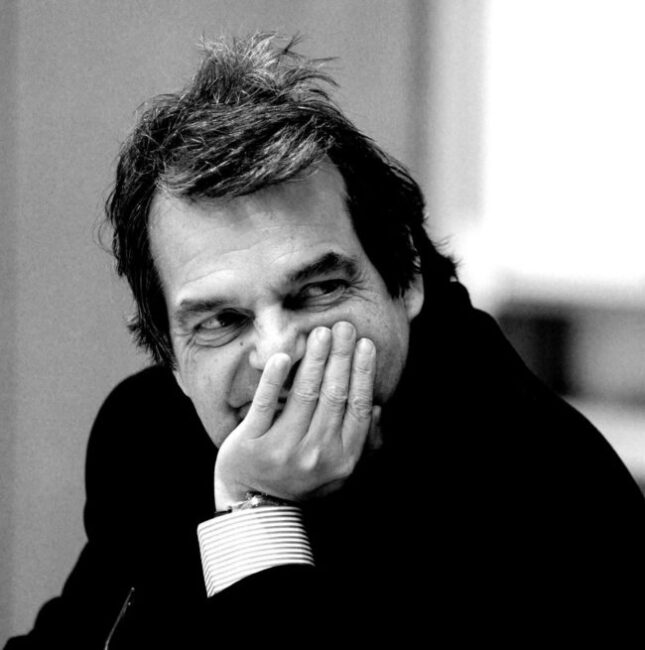

Melchor Terrero, artista da sempre, ha al suo attivo sette mostre personali a Santo Domingo e una a Miami, ha partecipato a settanta mostre collettive nazionali e venti internazionali e le sue opere fanno parte di collezioni pubbliche e private in molte città del mondo; è rappresentato in Spagna dalla Galeria Andrea di Alicante, e in Inghilterra dalla Redmondrian Fine Art Publishing di Devon.

MELCHOR TERRERO-CONTATTI

Email: melchorterrero@gmail.com

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/melchorterrero

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/melchorterrero/

The cheerful and carefree overweight world of the Naif by Melchor Terrero

The modern world constantly chases after models of beauty, aesthetic canons, all too often unattainable, which therefore have the consequence of making the individual feel inadequate, as if not corresponding to that ideal entails exclusion from society, marginalisation due to an excessively superficial approach to existence that seems to dictate the rules. However, there are artists in the contemporary world who wish to emphasise how not fitting within those rigid external guidelines generates a sense of freedom and self-confidence that makes the individual stripped of conventions and happy to be himself, to remain in his own skin. The artist I am going to tell you about today exalts the tendency to go against the box and, because of this, to savour life in all its nuances, even the most rounded.

After many centuries in which art had exalted beauty by reproducing the aesthetic models of the historical period to which the artists belonged, a short-circuit was generated in the 20th century, one that in fact subverted the rules and challenged all the fixed points of the academic guidelines, during which a rebellion against aesthetic harmony as classically understood took place, because the human body had to become an emanation of interiority, a connection between feeling and being regardless of whether its visible form was pleasing or not. At the beginning of the 20th century, it was Expressionism that opened the door to the distortion of forms to favour expressiveness that often had to move away from perfection, from the balance that had characterised previous centuries, to align itself with those often destabilising emotional depths; and the human body intended as the narration of those anxieties, sometimes resulting in extreme and dissolute attitudes to cover the voice of anxieties, was the protagonist of Egon Schiele’s painting.

A few years later, the theme was taken up and expanded by a great exponent of the School of London, Lucian Freud, who, with his naked and corpulent figures, wanted to highlight the weakness of the flesh understood both from a sexual point of view and from that of human frailty; what emerges from his large-scale paintings is the insecurity, the shyness generated by the consciousness of not belonging to the beautiful part of society, the more glossy, elegant, sober part, yet his characters almost defy those conventions, they show themselves as they are, in their nakedness that represents their way of being. Parallel to the interiorisation carried out by these two great masters, there was the work of another sacred monster of 20th century art, the Colombian Fernando Botero, who with the simplicity and spontaneity of an immediate and easily usable style, the Naif, chose to exalt the round world, that of people who refuse to be dictated to from the outside and live their weight in a serene, fulfilling way, almost suggesting to the observer that their life is perhaps happier because it is free of that frustrating pursuit of a model that is too often unattainable. Where the weight is told by Botero in a dreamy way, set in real atmospheres but almost part of a modern fairy tale, readapting to his point of view scenes of everyday life in which everything is seen in an extra-large way without losing grace, delicacy and charm, for the Dominican artist Melchor Terrero, on the other hand, roundness takes on the connotation of musicality, of joy that distinguishes the Caribbean peoples and that emerges from his engaging and colourful scenarios precisely by virtue of their narrative immediacy, of that being on a line between tropical everyday life and the dream of a better, carefree world, in which the ability to savour every single moment prevails over everything that dominates western culture, made up of complications, haste, and careerism, which, while giving the illusion of happiness, tends on the contrary to generate frustration, competitiveness and lack of satisfaction. What Terrero dwells on are the most typical images of his wonderful and colourful country, the fragments of daily work in the fields or the coquetry of his women who do not care about excessive weight; on the contrary, they proudly wear those roundnesses that make them feel charming, self-confident, underlining how the canons of beauty differ from country to country, from culture to culture.

Melchor Terrero observes his characters in their essence, in that attitude of searching for happiness in small things, the sense of fulfilment in those simple and repetitive gestures that after all constitute the very basis of existence, and then, once duty is over, let yourself go to pleasure, to fun, to celebration as the inhabitants of the wonderful island of Santo Domingo know how to do. The Latin American Naif is characterised by a lively, intense, colourful range of colours, just like the buildings, the clothes, the contrasts between sky and sea in which the people of that corner of the world are accustomed to live, so art cannot be detached from their daily reality, their nature, and Melchor Terrero in turn chooses shades akin to the lightness of happy living, of overcoming every difficulty with a smile, a moment of celebration with friends and then going back to their daily tasks. So, in him, overweight, roundness, become celebrations of interiority, elevation from an exterior model that is all too often unattainable in order to push on towards real life, that of imperfection, of the ability to feel at ease in one’s own clothes, no matter what size one is. The painting Pasarela makes an ironic comment on the law of fashion that wants very thin girls to walk on the catwalk, showing the observer how a woman of a more substantial weight can in any case appear fascinating, seductive, self-confident even when she is in the spotlight from which, if she were to be intimidated by the common view, she should feel intimidated. The protagonist, on the contrary, wears a bright colour and is proud to have the gazes of an enthusiastic and admiring audience on her, made up of people as round as she is, almost as if Terrero wanted to show the observer another possibility, a reality in which it might be the thin ones who look strange, as if joviality were the key to a different happiness.

The series Recoletoras de flores tells of the moment of work, of that daily toil that nonetheless allows the women protagonists to return home satisfied with having fulfilled their task, the one thanks to which they can feed their children, support their partners and husbands in the household economy; it is a world of values that of Melchor Terrero, a dimension in which what counts is interiority, good feelings, the substance that surpasses appearance, although even in those large dimensions, in those round shapes, one can find an unexpected beauty if one is capable of going beyond everything that social conventions impose, that ideal whose parameters have been defined arbitrarily and based on the superficiality of the image, without going into the interiority, because after all, the artist seems to be saying, happiness is much more attainable and within reach than what is being told. And it is through conviviality, the moments of sharing after having done one’s work, that it is possible to savour small moments of light-heartedness and joy, recounted by Melchor Terrero through one of his most engaging series, Musica y Ron, which includes both the dreamy canvas Serenata and Noche de parranda in which he interprets the sensations perceived during a night of fun, of lightness, of moving away from everyday life to enter into the world of music, always present in the Caribbean, and into that of cheerfulness, of the pleasure of living by dancing and savouring the good times to take with you into the days to come. The message of Terrero’s artworks is one of independence, freedom from rules and traditional canons, suggesting that perhaps it is precisely by hypothesising the world in reverse, the world in which imposed models decay and in which roundness means an abundance of emotions, sensations and naturalness, that the key to true happiness is hidden. Melchor Terrero, a lifelong artist, has seven solo exhibitions in Santo Domingo and one in Miami to his credit; he has participated in seventy national and twenty international group exhibitions and his artworks are part of public and private collections in many cities around the world; he is represented in Spain by Galeria Andrea in Alicante, and in England by Redmondrian Fine Art Publishing in Devon.