Il connubio tra varie forme d’arte appartiene alla contemporaneità tanto quanto nei secoli passati le diverse discipline tendevano a restare ciascuna all’interno del proprio ambito, come se una connessione non fosse possibile; al contrario i creativi attuali hanno ottenuto la libertà di poter sperimentare, mescolare e ispirarsi ad altri settori artistici dando vita a una contaminazione che arricchisce il loro linguaggio pittorico e scultoreo tanto quanto lo studio e l’approfondimento delle innovative tecniche che attingono ad antiche tradizioni artigiane trasformandosi in innovative esplorazioni espressive. L’artista di cui vi racconterò oggi ha effettuato un variegato percorso di approfondimento di differenti approcci che hanno contribuito a tratteggiare la sua personalità creativa mostrando quanto in realtà l’interazione tra le arti possa generare una forza rappresentativa potente e coinvolgente.

Se è vero che alcuni grandi maestri del passato, quelli che hanno lasciato un profondo segno nel corso della storia dell’arte mondiale, amavano circondarsi di note musicali durante l’esecuzione dei loro capolavori, come Leonardo da Vinci che sembra abbia chiamato al suo atelier diversi musicisti per farsi accompagnare nell’esecuzione della Monna Lisa o Delacroix che affrescò la chiesa di Saint Suplice a Parigi sulle note dell’organo, lo è anche che non esistendo le registrazioni non tutti potevano permettersi il lusso di avere un’intera orchestra al loro seguito. Dunque fu necessario attendere il Novecento per assistere al consolidarsi di un legame tra pittura e musica, essenziale per l’indole creativa di Vassily Kandinsky che trovava nelle note l’accompagnamento ideale a quei primordi di Astrattismo di cui gli fu attribuita la paternità. Le opere di Kandinsky erano di fatto un’illustrazione delle note che egli ascoltava, come se in virtù della non forma quella rappresentazione divenisse possibile. Ma anche Paul Klee amava lasciarsi trasportare dalle melodie classiche di Bach concretizzando l’energia che gli trasmettevano nelle sue suggestive tele; Henri Matisse, a sua volta appassionato di musica classica, in età matura incontrò il jazz da cui fu affascinato per il senso di libertà con la quale gli strumentisti affrontavano le note e le plasmavano armonicamente tanto quanto lui fece con le sue opere della. Anche Piet Mondrian fu conquistato dal jazz che conobbe quando fuggì a New York, durante la seconda guerra mondiale, ma anche dalle note divertenti e vivaci del Boogie Woogie a cui dedicò alcuni dipinti. Per non parlare poi dello stile libero che contraddistinse Jackson Pollock la cui Action Painting, con l’irruenza espressiva e la mancanza di regole strutturali figurative e cromatiche, poteva essere paragonata alle improvvisazioni virtuose dei musicisti jazz. Dunque la contaminazione tra le note musicali e il tratto figurativo diede vita a interazioni superbe in grado di conquistare il pubblico che comprendeva, grazie alla musicalità evidente dei dipinti di questi grandi esponenti dell’arte moderna, il messaggio nascosto all’interno di una rappresentazione Informale che non poteva essere compresa con l’intelletto bensì solo lasciandosi andare all’istinto e permettendo all’armonia e al canale comunicativo tra emotività e intenzione musicale delle opere, di far vibrare le corde interiori. È esattamente dalla sinergia tra musica e pittura che nasce e si sviluppa la cifra stilistica dell’artista ligure Luana Gibaldi, cresciuta letteralmente tra colori e trementina avendo una madre e un cugino pittori, peraltro con un solido percorso artistico, dunque la conseguenza naturale è stata che anche lei fosse travolta dalla creatività da cui si è lasciata condurre verso l’Astrattismo, il linguaggio più affine alla sua esigenza comunicativa proprio in virtù di un’indefinitezza funzionale a rappresentare anche il suo amore per la musica.

Malgrado la madre fosse un’artista tendente al figurativo naturalista, chi ne influenzò in maniera più forte il gusto stilistico fu suo cugino Salvatore Marrali, studente insieme a Emilio Vedova presso l’Accademia di Belle Arti di Firenze, da cui rimase colpita e affascinata per le linee sospese di grande impatto emozionale che caratterizzavano le opere di entrambi; gli inizi della Gibaldi furono orientati a studiare e rielaborare gli ideogrammi giapponesi adeguandoli al suo intento espressivo fino a farli diventare tratti distintivi di tele in cui ciò che era imprescindibile era esattamente quel senso di musicalità che le veniva dallo studio del pianoforte e che sentiva la necessità di imprimere nelle sue opere. Dunque i segni grafici cominciarono ad armonizzarsi al suo stile Informale attraverso il quale riusciva a dare sfogo alle sue sensazioni legate all’armonia di quella musica che per lei era fortemente legata all’atto creativo.

L’eredità materna invece, costituita dalla capacità di utilizzare il colore in maniera densa, quasi tridimensionale, per dipingere i grandi fiori che identificavano il suo stile, è stata rielaborata nell’interesse successivo verso la struttura materica che Luana Gibaldi infonde alle sue opere più recenti dove il segno grafico ha lasciato spazio a una persino maggiore indefinitezza, come se le emozioni avessero bisogno di più libertà e al tempo stesso di una consistenza che trova realizzazione solo in materiali inconsueti eppure incredibilmente efficaci per armonizzarsi al suo messaggio espressivo. Paste modellanti, malta, e ovviamente il colore, contribuiscono a trascinare l’osservatore nel mondo magnetico delle sensazioni che traspaiono dalle opere a cui talvolta non viene dato titolo per non interrompere il libero fluire della comunicazione tra l’intenzione dell’autrice e il ricevente che può così lasciarsi andare senza azionare il lato razionale, abbandonandosi letteralmente al proprio sentire; malgrado la concretezza di questa serie di opere, l’armonia musicale è sempre presente, quasi come se le pennellate, i vortici appena accennati si muovessero in circolo danzando al ritmo delle note fuoriuscenti dal pianoforte.

L’opera L’inizio, con la sua armonia cromatica tendente al ciclamino, sembra rivolgersi all’anima, perché è esattamente quest’ultima a essere stimolata dalla tonalità rosacea predominante, e infonde un senso di pace, come se in quel principio di cui parla il titolo vi fosse l’essenza di tutto, della vita da cui si genera molto altro, sulla base della direzione in cui l’individuo, più o meno consapevolmente, sceglie debba andare. La pasta modellante sembra quasi graffiata, stesa sulla carta Arches in maniera consistente per sottolineare l’importanza dell’origine da cui poi si possono diramare tutti i passi, la sequenza di causa ed effetto che determinerà la direzione dell’esistenza.

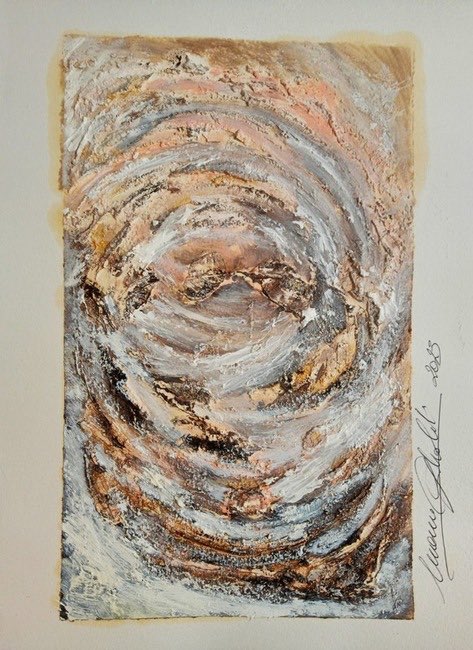

In Opera n. 1 invece le tonalità sono più cipriate, terrose, eppure sempre incredibilmente tenui, positive, come se Luana Gibaldi osservasse il mondo con sguardo morbido, contrariamente a quanto potrebbe apparire a causa della sua necessità di arricchire di consistenza le sue tele, guidando il fruitore in quell’universo artistico e, ancora una volta, musicale che ha costituito la sua vita e la sostanza del suo percorso. Le larghe pennellate vanno, anche in quest’opera, a generare una sorta di vortice, come se volesse sottolineare l’inseguirsi di quelle note attraverso cui nasce una sinfonia e dunque il riferimento del titolo potrebbe anche essere riconducibile proprio a quello delle composizioni classiche; perdersi all’interno delle sfumate tonalità significa effettuare un tuffo nella delicatezza dell’anima, quel mondo troppo spesso messo a tacere per il timore che venga ferito.

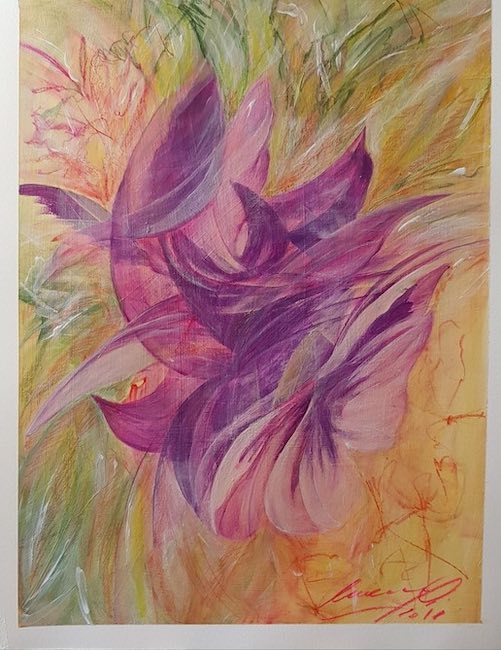

Ed è proprio questo forse il senso dell’opera Freedom, in cui Luana Gibaldi rinuncia alla materia e sceglie la bidimensionalità dell’acrilico e dell’acquerello su carta, un modo per sottolineare quanto tutto ciò che è spesso lasciato in silenzio nelle pieghe della quotidianità abbia invece bisogno di liberarsi, di trovare un suo canale espressivo in virtù del quale lasciar fluire quella leggerezza, rappresentata ancora una volta dal colore rosa intenso, fondamentale per smettere di doversi nascondere. Dunque supporti diversi, tanto quanto differenti sono i materiali usati da questa poliedrica artista che per seguire la sua inclinazione creativa si è spostata a Venezia dove ha studiato la tecnica incisoria che contraddistingue alcune sue opere in cui la lastra di zinco fa da base all’incisione calcografica, senza però mai rinunciare a quella tendenza all’approfondimento che è essenza stessa del suo approccio artistico.

Luana Gibaldi ha al suo attivo la partecipazione a importanti mostre collettive, come la Biennale di Mantova presenziata dagli storici dell’arte Vittorio Sgarbi e Philippe Daverio, e molti eventi dedicati alla tecnica incisoria, per cui è inserita nell’Albo Nazionale Incisori.

LUANA GIBALDI-CONTATTI

Email: luanagibaldi@blu.it

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/luana.gibaldi

https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100091763344926

Luana Gibaldi’s Informal Art, where Japanese ideograms and matter dance with music

The combination of various art forms belongs to the contemporary world just as much as in past centuries the various disciplines tended to remain each within their own sphere, as if a connection were not possible. On the contrary, today’s creative artists have been given the freedom to experiment, mix and draw inspiration from other artistic fields, giving rise to a contamination that enriches their pictorial and sculptural language just as much as the study and deepening of innovative techniques that draw on ancient artisan traditions, transforming them into innovative expressive explorations. The artist I am going to tell you about today has pursued a varied path of in-depth study of different approaches that have contributed to outlining her creative personality, showing how in reality the interaction between the arts can generate a powerful and engaging representational force.

If it is true that some great masters of the past, those who have left a profound mark on the history of world art, loved to surround themselves with musical notes during the execution of their masterpieces, such as Leonardo da Vinci who seems to have called several musicians to his atelier to be accompanied in the execution of the Mona Lisa or Delacroix who frescoed the church of Saint Suplice in Paris to the notes of the organ, it is also true that since recordings did not exist, not everyone could afford the luxury of having an entire orchestra in tow. So it was necessary to wait until the 20th century to witness the consolidation of a link between painting and music, which was essential to the creative nature of Vassily Kandinsky, who found in notes the ideal accompaniment to those beginnings of Abstractionism for which he was attributed the paternity. Kandinsky‘s artworks were in fact an illustration of the notes he heard, as if by virtue of non-form that representation became possible. But also Paul Klee loved to let himself be carried away by Bach’s classical melodies, concretising the energy they conveyed to him in his evocative canvases; Henri Matisse, himself a classical music enthusiast, encountered jazz in his later years and was fascinated by it because of the sense of freedom with which the instrumentalists approached the notes and moulded them harmonically, just as he did with his works of art. Piet Mondrian was also won over by jazz, which he encountered when he fled to New York during the Second World War, but also by the fun and lively notes of the Boogie Woogie to which he dedicated some paintings.

Not to mention the free style that distinguished Jackson Pollock whose Action Painting, with its expressive impetuosity and lack of figurative and chromatic structural rules, could be compared to the virtuoso improvisations of jazz musicians. Thus, the contamination between musical notes and the figurative trait gave rise to superb interactions capable of conquering the public who understood, thanks to the evident musicality of the paintings of these great exponents of modern art, the message hidden within an Informal representation that could not be understood with the intellect but only by letting oneself go to instinct and allowing the harmony and the communicative channel between emotionality and the musical intention of the artworks to vibrate the inner chords. It is precisely from the synergy between music and painting that the stylistic trait of Ligurian artist Luana Gibaldi was born and developed. She literally grew up amidst colours and turpentine, having a mother and a cousin who were painters, and had a solid artistic background, so it was only natural that she too was overwhelmed by creativity, which led her towards Abstractionism, the language most akin to her communicative needs, precisely because of an indefiniteness that also represented her love for music. Despite the fact that her mother was an artist with a tendency towards naturalist figurative art, the one who most strongly influenced her stylistic taste was her cousin Salvatore Marrali, a student together with Emilio Vedova at the Accademia di Belle Arti in Florence, by whom she was struck and fascinated by the suspended lines of great emotional impact that characterised the artworks of both; Gibaldi‘s beginnings were oriented towards studying and re-elaborating Japanese ideograms, adapting them to her expressive intentions until they became distinctive features of canvases in which what was essential was precisely that sense of musicality that came to her from studying the piano and that she felt she needed to imprint in her artworks.

Thus the graphic signs began to harmonise with her Informal style through which she was able to give vent to her feelings connected to the harmony of that music that for her was strongly linked to the creative act. Her mother’s inheritance, on the other hand, consisting of her ability to use colour in a dense, almost three-dimensional manner to paint the large flowers that identified her style, was reworked in her later interest in the material structure that Luana Gibaldi infuses into her more recent artworks where the graphic sign has given way to an even greater indefiniteness, as if her emotions needed more freedom and at the same time a consistency that only finds realisation in unusual yet incredibly effective materials to harmonise with her expressive message. Modelling pastes, mortar and, of course, colour, contribute to drawing the observer into the magnetic world of sensations that transpire from the works, which are sometimes untitled so as not to interrupt the free flow of communication between the author’s intention and the receiver, who can thus let himself go without activating the rational side, literally abandoning himself to his own feeling; despite the concreteness of this series of artworks, the musical harmony is always present, almost as if the brushstrokes, the barely hinted at swirls, were moving in circles, dancing to the rhythm of the notes coming out of the piano. The work The Beginning, with its chromatic harmony tending towards cyclamen, seems to address the soul, because it is precisely the soul that is stimulated by the predominant rosy hue, and it instils a sense of peace, as if in that principle of which the title speaks there is the essence of everything, of life from which much else is generated, based on the direction in which the individual, more or less consciously, chooses to go. The modelling paste seems almost scratched, spread out on Arches paper in a consistent manner to emphasise the importance of the origin from which all the steps can then branch out, the sequence of cause and effect that will determine the direction of existence.

In Opera n. 1, on the other hand, the tones are more powdery, earthy, yet always incredibly soft, positive, as if Luana Gibaldi were observing the world with a soft gaze, contrary to what might appear due to her need to enrich her canvases with consistency, guiding the viewer into that artistic and, once again, musical universe that has constituted her life and the substance of her path. The broad brushstrokes go, also in this work, to generate a sort of vortex, as if to emphasise the chasing of those notes through which a symphony is born, and thus the reference of the title could also be traced back precisely to that of classical compositions; to lose oneself within the nuanced tones means taking a plunge into the delicacy of the soul, that world too often silenced for fear that it will be wounded. And this is perhaps the sense of the work Freedom, in which Luana Gibaldi renounces the material and chooses the two-dimensionality of acrylic and watercolour on paper, a way of emphasising how all that is often left in silence in the folds of everyday life needs instead to free itself, to find its own channel of expression by virtue of which it can let that lightness flow, represented once again by the intense pink colour, which is fundamental in order to stop having to hide. So different are the supports, just as different as the materials used by this multifaceted artist who, in order to follow her creative inclination, moved to Venice where she studied the engraving technique that characterises some of her artworks in which the zinc plate forms the basis of the chalcographic engraving, without ever renouncing that tendency towards in-depth study that is the very essence of her artistic approach. Luana Gibaldi has participated in important group exhibitions to her credit, such as the Mantua Biennial attended by art historians Vittorio Sgarbi and Philippe Daverio, and many events dedicated to engraving technique, for which she is listed in the National Register of Engravers.