La durezza del vivere contemporaneo induce spesso gli artisti a liberare le proprie emozioni in maniera istintiva, primordiale, senza alcun freno stilistico perché ciò che è davvero importante è portare alla luce tutto quel vortice interiore che non riesce a trovare altra voce se non quella dell’espressione pittorica; dunque il distacco dalla forma osservata è funzionale all’esigenza di non avere regole, schemi a cui attenersi o linee guida che romperebbero quel libero fluire. Alcuni creativi mettono in atto questo processo di liberazione in maniera impulsiva usando solo il colore nella maniera più indefinita possibile, mentre altri hanno al contrario bisogno di delimitare contorni e figure, seppure su forme inconosciute dall’occhio, all’interno dei quali si possono perdere e spingere verso l’indagine dei significati della realtà osservata o percepita. L’artista di cui vi parlerò oggi utilizza quest’ultimo approccio per scoprire lo spazio circostante ma anche quello interiore, silenzioso eppure costantemente udibile se solo si pone la giusta attenzione.

Il tema del distacco da ogni realtà osservata cominciò a emergere nel primo ventennio del Novecento, quando cioè alcuni artisti avvertirono la necessità di affrancarsi dall’arte accademica e dalla riproduzione estetica tendente alla perfezione dei soggetti ritratti per affermare la supremazia dell’arte rispetto a ciò che l’occhio poteva cogliere intorno a sé e per suggerire quanto in fondo i colori e le non forme potessero avere una vita propria più vicina alla purezza del gesto creativo perché non condizionata dalla mente o dalla soggettività dell’esecutore dell’opera. Tuttavia il maestro considerato fondatore dell’Astrattismo, Vassily Kandinsky, si soffermò su quella capacità della forma indefinita di essere accompagnamento e amplificazione del mondo interiore, di quel sentire che non poteva prescindere dall’essere umano; nell’eseguire le sue opere addirittura si lasciava trasportare dalle note musicali perché l’armonia del suono aveva il potere di indurre l’inconscio a manifestarsi fino a giungere a connettersi con il pennello che diveniva semplicemente mezzo attraverso il quale raccontare sotto forma di linee e di balletto cromatico quelle sensazioni che liberamente fluivano. Poco dopo però dalla parte opposta dell’Europa, prese piede un movimento pittorico, il De Stijl, che contrariamente alle linee guida di Kandinsky, voleva invece affermare l’indipendenza del gesto plastico da qualsiasi contaminazione emozionale, da ogni interferenza della soggettività sulla tela che doveva così distaccarsi completamente dall’esecutore; l’utilizzo dei soli colori primari, delle forme rettangolari o quadrate ma soprattutto la mancanza di emozione che pertanto non risultava coinvolgente per l’osservatore, condussero le figure chiave del movimento, Piet Mondrian e Theo Van Doesburg, a essere isolate dagli altri artisti di quel periodo che pur volendo mantenere la geometricità come base della loro ricerca, decisero però di ampliare la gamma cromatica e di inserire anche le linee diagonali e molte altre figure comprese quelle tondeggianti, considerate invece ambigue e dunque escluse dal De Stijl. Quella nuova corrente prese il nome di Astrattismo Geometrico e, seppur mantenendo il distacco dall’emozione evocata dalle opere di Kandinsky, risultò essere più comprensibile e coinvolgente per il pubblico che si lasciava trasportare da una maggiore ampiezza di tonalità e da quell’intreccio di linee e geometricità che lo astraevano e distaccavano dalla confusa realtà quotidiana, rassicurandolo. L’artista bresciana Annamaria Giugni, con la libertà tipica del periodo artistico contemporaneo, si avvicina all’Astrattismo in maniera singolare perché se da un lato mantiene un contatto con la geometria, pur facendo prevalere la morbidezza e la sinuosità delle curve e dei cerchi, dall’altro infonde nelle sue tele emozione e riflessione, quell’indagare sulle grandi questioni della vita che appartengono all’uomo e da cui l’arte non può prescindere, certamente non la sua.

Non solo, ciò che è essenziale per l’artista è la correlazione tra interno ed esterno, tra il sentire e l’essere in un dialogo costante che non può rimanere inascoltato, tutt’altro, ha invece bisogno di essere meditato, indagato, scoperto con un approccio mentale ma al contempo guidato dall’emozione perché è quest’ultima la guida per scendere verso le profondità dell’animo e per mettersi in connessione con le energie sottili apparentemente silenziose ma in realtà sottilmente determinate a emergere.

È questo il percorso che le opere di Annamaria Giugni stimolano a intraprendere, con quei colori morbidi e vivaci, con quelle linee quasi ipnotiche che non possono fare a meno di affascinare l’osservatore costringendolo a porsi in posizione di ascolto, di apertura verso un contatto tra mente e anima per capire quanto profonde siano le radici che li legano; nell’opera Fondale dell’anima l’artista mette in evidenza i frammenti che compongono quella delicata e fragile parte dell’essere umano troppo spesso lasciata in un angolo nascosto per non essere ferita, per non essere calpestata da un altro individuo o dagli eventi. Le tonalità scelte sono quelle delle emozioni, il blu della malinconia, il rosso della passione, il giallo dell’entusiasmo, il viola delle vibrazioni interiori, mentre le forme che a ciascun colore si legano cambiano divenendo più piccole o più grandi a seconda di quanto profonda sia la traccia che l’esperienza e il ricordo hanno lasciato sull’anima. Il grembo silenzioso dentro il quale si muovo quelle sensazioni sembra essere immobile eppure la sensazione è di lenta fluttuazione, come se tutto possa cambiare e modificare la propria rilevanza sulla base di nuove esperienze in procinto di sopraggiungere.

Nella tela Logos la Giugni sottolinea l’importanza della sinergia tra pensiero e parola, quella evidenziata e auspicata dai grandi filosofi greci, che rende l’essere umano in grado di filtrare l’istinto e le sensazioni apparentemente ingestibili grazie all’intervento della capacità di riflettere, di ricordare, di elaborare tutto ciò per cui è necessario interporre un argine alla parte più impulsiva; nella tela infatti le tonalità sono più nette, determinate, soprattutto nell’immagine al centro dell’opera, quella dunque legata al verbo che fuoriesce lentamente e in maniera articolata solo dopo aver toccato la consapevolezza della coscienza e dell’interiorità. Tuttavia intorno a quella razionalità esiste il lato più emozionale, quello che non verrà mai ridotto al silenzio bensì farà da sfondo e da base di partenza per l’elaborazione della logica che, a sua volta, non potrà prescindere dall’impulso iniziale alla riflessione stimolato proprio dal sentire istintivo.

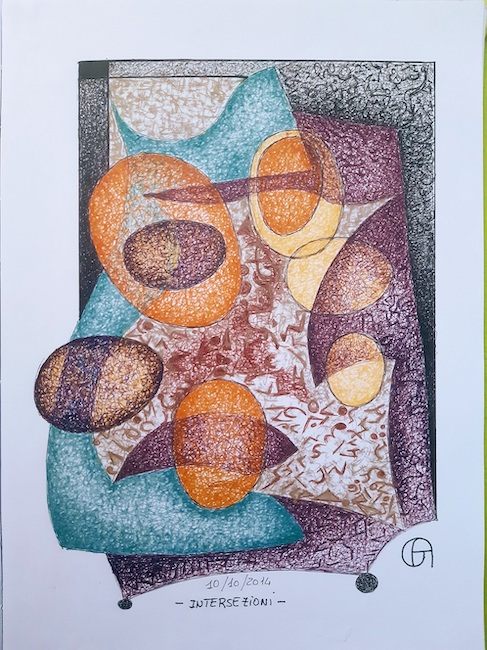

E ancora in Intersezioni l’artista, ancora una volta, gioca con gli opposti, con il sentire e con il riflettere che sono necessari e motore stesso della vita e dell’evoluzione, componendo quella ricchezza interiore che si concretizza proprio nel bilanciamento tra i due estremi in maniera personale definendo così le peculiarità, le caratteristiche di ciascuno. Qui il colore non è dato attraverso la pittura acrilica bensì la Giugni usa china e pennarelli infondendo all’opera grafica uno stile vicino al Puntinismo funzionale a sottolineare l’importanza di quelle frammentazioni a cui quotidianamente l’individuo è sottoposto e con cui può ricostruirsi in maniera differente attraverso la meditazione, la presa d’atto dell’importanza degli eventi e delle circostanze, e la capacità di analizzare per poi ricomporre un nuovo sé, più consapevole, più evoluto anche grazie alle interazioni con l’esterno. Quando si sposta verso la narrazione, o meglio l’interrogazione, di quei temi che da sempre affascinano l’uomo senza che sia però capace di dargli una spiegazione, una risoluzione, perché non tutto può essere spiegabile attraverso la ragione o conoscibile dalla capacità umana, lo stile della Giugni si fa più ipnotico, più tendente a un Surrealismo Astratto dove colori e forme si intrecciano per dare vita a quegli intrecci energetici che si susseguono e si generano a dispetto dell’abilità dell’essere umano di poterle comprendere e a cui spesso deve arrendersi.

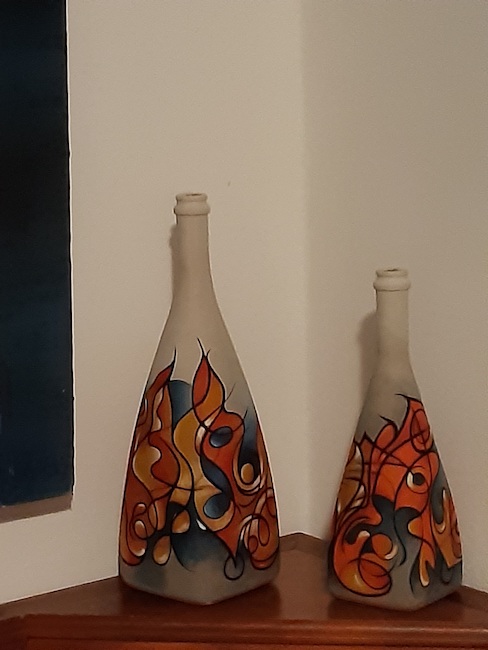

Non solo pittrice ma anche decoratrice di ceramiche Annamaria Giugni ha creato una linea di anfore, vasi, bottiglie e vasi in cui imprime in maniera artigianale le sue forme astratte, giocando con le superfici e adattando le sue immagini alle curvature degli oggetti che verranno personalizzati; nel corso della sua carriera ha partecipato a mostre personali in Italia e una molto importante a Hong Kong e una mostra personale in provincia di Brescia.

ANNAMARIA GIUGNI-CONTATTI

Email: annamariagiugni178@gmail.com

Sito web: http://annamariagiugni.blogspot.com/

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100008659331977

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/annamariagiugni/

Annamaria Giugni’s Abstractionism, where sinuous shapes investigate the depths of the mind and soul

The harshness of contemporary life often induces artists to release their emotions in an instinctive, primordial manner, without any stylistic restraint, because what is really important is to bring to light all that inner vortex that cannot find any other voice but that of pictorial expression; thus detachment from the observed form is functional to the need not to have rules, schemes to follow or guidelines that would break that free flow. Some creatives implement this process of liberation in an impulsive manner using only colour in the most indefinite manner possible, while others, on the contrary, need to delimit contours and figures, albeit on forms unknown to the eye, within which they can lose themselves and push towards the investigation of the meanings of the reality observed or perceived. The artist I am going to talk about today uses this latter approach to discover the surrounding space but also the inner space, silent yet constantly audible if one only pays the right attention.

The theme of detachment from any observed reality began to emerge in the first twenty years of the twentieth century, when some artists felt the need to free themselves from academic art and from the aesthetic reproduction tending towards the perfection of the subjects portrayed, in order to affirm the supremacy of art over what the eye could perceive around it and to suggest how colours and non-forms could have a life of their own closer to the purity of the creative gesture because it was not conditioned by the mind or subjectivity of the artwork’s executor. However, the master considered to be the founder of Abstractionism, Vassily Kandinsky, dwelled on the capacity of the undefined form to accompany and amplify the inner world, of that feeling that could not be separated from the human being; in executing his paintings he even allowed himself to be carried away by musical notes because the harmony of sound had the power to induce the unconscious to manifest itself to the point of connecting with the brush that became simply a means through which to recount in the form of lines and a chromatic ballet those sensations that flowed freely. Shortly afterwards, however, on the opposite side of Europe, a pictorial movement took hold, the De Stijl, which, contrary to Kandinsky’s guidelines, wanted to affirm the independence of the plastic gesture from any emotional contamination, from any interference of subjectivity on the canvas, which thus had to be completely detached from the executor; the use of only primary colours, rectangular or square shapes and above all the lack of emotion, which was therefore not involving the observer, led the key figures of the movement, Piet Mondrian and Theo Van Doesburg, to be isolated from the other artists of the period who, while wishing to maintain geometricity as the basis of their research, decided to broaden the range of colours and insert diagonal lines and many other figures, including rounded ones, which were considered ambiguous and therefore excluded from De Stijl. This new current took the name of Geometric Abstractionism and, although it maintained the detachment from the emotion evoked by Kandinsky’s artworks, it proved to be more comprehensible and involving for the public who let be carried away by a greater range of tones and by that interweaving of lines and geometricity that distanced and detached them from the confused everyday reality, reassuring them.

The Brescian artist Annamaria Giugni, with the freedom typical of the contemporary artistic period, approaches Abstractionism in a singular way because if on the one hand she maintains a contact with geometry, while letting the softness and sinuosity of curves and circles prevail, on the other hand she infuses her canvases with emotion and reflection, that investigation of the great questions of life that belong to man and from which art cannot prescind, certainly not hers. Not only that, but what is essential for the artist is the correlation between inside and outside, between feeling and being in a constant dialogue that cannot go unheard, on the contrary, it needs to be meditated upon, investigated, discovered with a mental approach but at the same time guided by emotion because it is the latter that is the guide to descend towards the depths of the soul and to connect with the subtle energies apparently silent but in reality subtly determined to emerge. This is the path that Annamaria Giugni’s paintings stimulate to take, with their soft and lively colours, with their almost hypnotic lines that cannot fail to fascinate the observer, forcing him to place himself in a position of listening, of openness towards a contact between mind and soul to understand how deep are the roots that bind them; in the artwork Fondale dell’anima the artist highlights the fragments that make up that delicate and fragile part of the human being, too often left in a hidden corner so as not to be wounded, not to be trampled on by another individual or by events. The shades chosen are those of the emotions, the blue of melancholy, the red of passion, the yellow of enthusiasm, the purple of inner vibrations, while the shapes that are linked to each colour change, becoming smaller or larger depending on how deep the trace that experience and memory have left on the soul. The silent womb within which these sensations move seems to be motionless and yet the sensation is one of slow fluctuation, as if everything could change and modify its relevance on the basis of new experiences about to arrive. In the canvas Logos, Giugni emphasises the importance of the synergy between thought and word, the synergy highlighted and hoped for by the great Greek philosophers, which makes the human being capable of filtering instinct and apparently unmanageable sensations thanks to the intervention of the capacity to reflect, to remember, to elaborate everything for which it is necessary to interpose a barrier to the more impulsive part; in the canvas, in fact, the tones are sharper, more determined, especially in the image at the centre of the painting, the one therefore linked to the verb that emerges slowly and articulately only after touching the awareness of conscience and interiority.

However, around that rationality there is the more emotional side, the one that will never be reduced to silence but will act as a background and starting point for the elaboration of logic, which, in turn, cannot be separated from the initial impulse to reflection stimulated by instinctive feeling. In Intersections, the artist once again plays with opposites, with feeling and reflection, which are necessary and the very engine of life and evolution, composing that inner richness that is realised precisely in the balancing of the two extremes in a personal way, thus defining the peculiarities and characteristics of each. Here the colour is not given by acrylic paint by Giugni but using Indian ink and felt-tip pens, imbuing the graphic work with a style close to Pointillism, underlining the importance of those fragmentations to which the individual is subjected every day and which he can use to reconstruct himself in a different way through meditation, awareness of the importance of events and circumstances, and the ability to analyse and then recompose a new self, more aware, more evolved thanks also to interactions with the outside world. When she moves towards the narration, or rather the questioning, of those themes that have always fascinated man without him being able to give an explanation, a resolution, because not everything can be explained through reason or known by human ability, Giugni’s style becomes more hypnotic, more inclined towards an Abstract Surrealism where colours and shapes intertwine to give life to those energetic interweavings that follow one another and are generated in spite of the human being’s ability to understand them and to which he often has to surrender. Not only a painter but also a ceramics decorator, Annamaria Giugni has created a line of amphorae, vases, bottles and pots in which she imprints her abstract forms in an artisanal manner, playing with the surfaces and adapting her images to the curvatures of the objects that will be personalised. During her career she has taken part in personal exhibitions in Italy and a very important one in Hong Kong, as well as a personal exhibition in the province of Brescia.