Il ritratto nella modernità sembra aver perduto l’essenza per la quale era stato concepito alla sua nascita, trasformandosi di fatto nella rappresentazione di un’emozione, di un’espressione di un volto comune, di una persona qualunque, in cui ciascun osservatore possa ritrovarsi e identificarsi attraverso il sentire, senza che lo sguardo sia distratto da un’icona o da un personaggio noto. Tuttavia alcuni artisti mantengono inalterata la tradizione del ritratto attraverso un proprio personale stile, come la protagonista di oggi che racconta le icone della nuova nobiltà contemporanea.

Fin dalle prime forme creative l’uomo ha sempre desiderato immortalare se stesso affinché il suo volto rimanesse per sempre a ricordo del suo passaggio nella vita; nell’antico Egitto le effigi rappresentanti i Faraoni erano ovunque, dai muri delle piramidi ai palazzi, dai sarcofagi agli oggetti in terracotta. Ma anche i Greci utilizzarono il ritratto, soprattutto quello scultoreo per narrare i filosofi e gli eroi del mito; e ancora i Romani immortalarono i re e i personaggi fondamentali nella vita dell’Impero. Con l’avvento della pittura la nobiltà non poté sottrarsi al fascino dell’avere un ritratto di famiglia all’interno delle dimore sontuose e rappresentative così, nel corso dell’avvicendarsi dei secoli, i grandi maestri delle varie epoche hanno dipinto volti di re, regine, duchi, contesse, permettendo loro di divenire icone della storia dell’arte. La scuola Fiamminga aprì le porte alle effigi dei signori dell’alta società, quei potenti affrancati dalla condizione di peccatori risalente alle convinzioni del Medioevo, i cui ritratti contraddistinti da colori scuri e posizione a tre quarti di Jan van Eyck e Albrecht Dürer sono divenuti simbolo di un’epoca ma anche della loro rilevanza storica; nel Rinascimento italiano, che invece preferì, salvo qualche eccezione, colori chiari e luminosi e le posizioni di profilo dei volti protagonisti, tutti i più grandi maestri si dedicarono al ritratto, da Raffaello a Leonardo da Vinci, la cui Monna Lisa è un’icona pittorica senza tempo, da Sandro Botticelli a Piero della Francesca, il cui Doppio ritratto dei Duchi d’Urbino affascina tutt’oggi appassionati di tutto il mondo. La staticità delle pose e l’attenzione ai soli volti cominciò a essere superata nei periodi artistici del Barocco e del Rococò in cui i pittori cominciarono non solo a interpretare l’espressione interiore dei loro soggetti bensì anche il momento dell’azione del corpo, come il sollevare una mano nel momento del dialogo, ed enfatizzando anche l’opulenza e la ricchezza delle vesti dei signori immortalati; Pieter Paul Rubens, Rembrandt, Gian Lorenzo Bernini furono i massimi rappresentanti di questi due stili. Con il Realismo invece il ritratto perse la sua funzione iniziale di fotografia pittorica della nobiltà o dei nuovi signori della borghesia poiché l’interesse degli artisti si spostò sulla gente comune, sui lavoratori più umili, le loro sofferenze nel vivere, la faticosa routine della quotidianità e le lotte per ottenere maggiori diritti; con il sopraggiungere del Novecento invece vi fu un ritorno alla narrazione di volti di signori, di borghesi e poi, con l’avvicinarsi agli anni Cinquanta, anche delle nuove icone cinematografiche. Da Gustav Klimt a Egon Schiele, da Picasso a Modigliani, da Tamara de Lempicka a Andy Warhol, tutti ebbero un ruolo di primo piano nell’evidenziare e mettere in luce volti che hanno acquisito notorietà anche grazie alla loro produzione artistica. La pittrice norvegese Zoja Sperstad riprende il tema del ritratto nella sua accezione più tradizionale, immortalando le personalità nobiliari contemporanee in tutta la loro regalità ed eleganza ma anche rivelandone i veri colori, quelli più emozionali che in virtù dell’occhio e dell’abilità descrittiva dell’artista vengono svelati anche all’osservatore.

Il suo stile è Espressionista, per l’utilizzo della gamma cromatica spesso irreale e legata più alla personalità e alle caratteristiche tipiche del personaggio che ritrae, che non ai palazzi e ai giardini in cui colloca i suoi protagonisti; ma presenta anche le caratteristiche del Realismo Magico per la tendenza a narrare i suoi soggetti come se fossero sospesi, avvolti da un’atmosfera sognante, immersi nella natura circostante che si accorda perfettamente al loro stato d’animo, sereno e incantato.

Immortala i nobili che ruotano intorno a Villa Cesarina nella località di Valganna che periodicamente frequenta, di proprietà del Duca di Valganna ma aperta a eventi in cui arte e cultura sono protagonisti; la cornice incantata in cui è collocato il palazzo fa da coprotagonista a molte delle opere in cui emergono le personalità eleganti ma sfaccettate delle donne e degli uomini che appartengono alla famiglia o che ruotano intorno a essa, permettendo a Zoja Sperstad di lasciarne emergere le peculiarità espressive, l’approccio alla vita che ciascuno di loro, nella propria sfaccettata individualità, dimostra.

La tela Violetta è dedicata alla campionessa internazionale di ginnastica artistica e coreografa Violetta Ballirano, rappresentata durante ciò che ama di più fare, cioè armonizzare il proprio corpo alla musica, alla connessione tra precisione esecutiva ed emotività che contraddistingue discipline ferree eppure incredibilmente morbide nell’espressione corporea; la Sperstad la racconta poeticamente immersa nella natura davanti a uno scorcio di Villa Cesarina, luogo che la ginnasta frequenta e in cui ha spesso la possibilità di esibirsi. La perfezione del movimento è narrata attraverso il corpo, la concentrazione e la gioia nell’eseguire la sua performance sono invece descritte dal suo sguardo, dalla sua espressione sicura e al tempo stesso appagata nel fare ciò che ama.

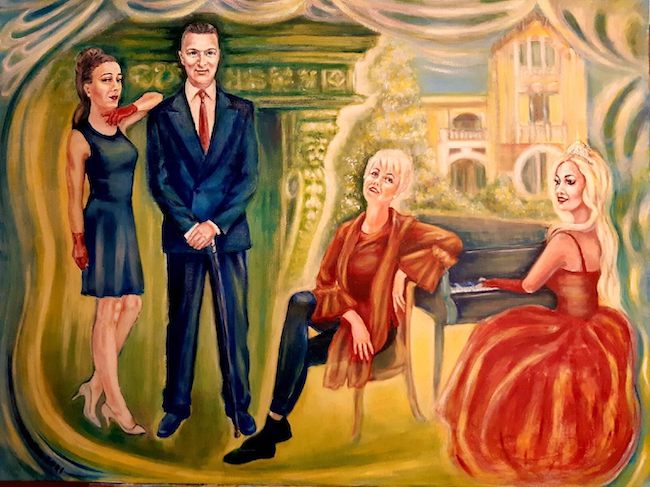

Il dipinto Famiglia di Villa Cesarina è invece dedicato, secondo la maniera più classica, al ritratto di famiglia, quell’immortalare i componenti di una dinastia nobile, sopravvissuti alla contemporaneità e in grado di apportare un contributo aprendo le porte della loro dimora per promuovere moda, arte, letteratura, musica, tutto ciò che è in grado di elevare gli animi e di spostare l’attenzione verso qualcosa che sia in grado di distogliere dalla realtà quotidiana diffondendo al tempo stesso la cultura; in questa tela la posa dei personaggi raccontati è quella più tradizionale, quasi in stile Rococo per la caratteristica di raffigurare i personaggi nella piena consapevolezza di essere ritratti, scegliendo la movenza o l’atteggiamento più consono a ciò che vogliono esprimere all’osservatore, osservando diretti e con sicurezza l’esecutrice dell’opera come se si trovassero di fronte all’obiettivo di un fotografo. L’aderenza al Realismo Magico la spinge però a sospendere il luogo e il collocamento nello spazio circostante i personaggi, a mescolare le scene come se ciascuno di loro portasse con sé il proprio mondo emozionale, il posto in cui preferiscono trattenersi, perché ciò che davvero conta è l’atmosfera che circonda l’edificio, sia all’esterno che al suo interno.

L’amore di Zoja Sperstad per il luogo fiabesco che ospita la famiglia del Duca di Valganna emerge forse ancora di più nella tela Villa Cesarina in cui la dimora si trasforma in assoluta protagonista della tela, con le sue tonalità chiare e luminose, circondata da una natura che non può fare a meno di diventare cornice all’interno della quale l’artista pone il Duca con sua moglie nella loro veste più ufficiale, nella loro espressione più solenne ma anche serena per il piacere di trovarsi immersi in uno scenario tanto accogliente.

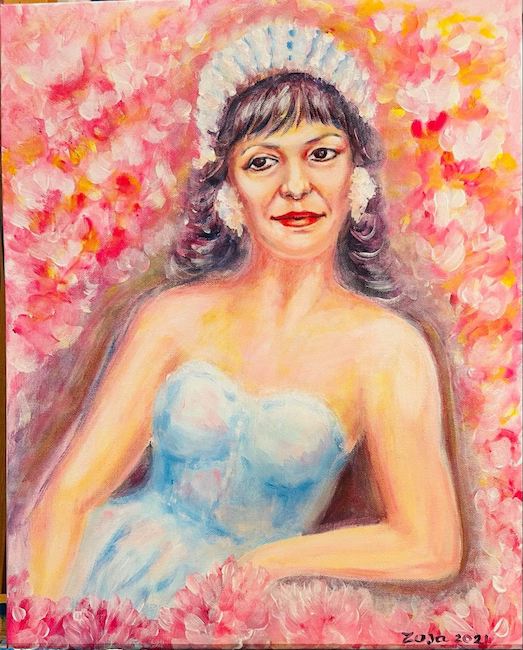

Nell’opera The creators of masterpieces (I creatori di capolavori) l’artista abbandona il ritratto nobiliare e si sposta su atmosfere più universali, più orientate a evidenziare il rapporto tra essere umano e natura attraverso la bellezza, la perfezione dell’una in correlazione all’altro, descrivendo la donna protagonista come avvolta in un bozzolo protettivo in cui la nudità rappresenta il bisogno di guardarsi dentro e al tempo stesso proteggere un’interiorità fragile, delicata, che proprio dalla natura, intesa come naturalezza, viene curata. Racconta un mondo sospeso Zoja Sperstad, decontestualizzando, ancora una volta, la protagonista della tela per collocarla in un luogo ideale, quello dell’anima, dentro il quale molto spesso l’uomo contemporaneo desidera nascondersi per coltivare ciò che viene perduto nella quotidianità.

Zoja Sperstad ha all’attivo molte mostre personali in Norvegia, Russia, Italia e Francia, e le sue opere sono state esposte in mostre collettive a Parigi, Venezia, Pesaro, Milano, Tiblisi (Georgia), in Finlandia, Norvegia, Russia e collabora continuativamente per l’organizzazione di eventi d’arte e cultura presso Villa Cesarina in Valganna.

ZOJA SPERSTAD-CONTATTI

Email: zojasperstad@live.no

Sito web: https://zojasperstadakantus-com.webnode.com/om-meg/

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/zoja.sperstad

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/zojasperstad/

The atmosphere of nobility in portraits halfway between Magic Realism and Expressionism by Zoja Sperstad

In modern times the portrait seems to have lost the essence for which it was conceived at its birth, transforming itself into the representation of an emotion, an expression of a common face, of an ordinary person, in which each observer can find himself and identify through feeling, without his gaze being distracted by an icon or a well-known character. However, some artists maintain the tradition of portraiture through their own personal style, like today’s protagonist who tells of the icons of the new contemporary nobility.

From the earliest creative forms, man has always wanted to immortalise himself so that his face would remain forever as a reminder of his passage through life; in ancient Egypt, effigies of Pharaohs were everywhere, from the walls of pyramids to palaces, from sarcophagi to terracotta objects. But the Greeks too used portraits, especially sculpture, to narrate philosophers and mythical heroes; and the Romans immortalised kings and key figures in the life of the Empire. With the advent of painting, the nobility could not escape the fascination of having a family portrait in their sumptuous and representative homes, and so, over the centuries, the great masters of the various eras painted the faces of kings, queens, dukes and countesses, allowing them to become icons of art history. The Flemish school opened the door to the portraits of the lords of high society, those powerful people freed from the condition of sinners dating back to the convictions of the Middle Ages, whose portraits marked by dark colours and three-quarter position by Jan van Eyck and Albrecht Dürer have become symbols of an era but also of their historical importance; in the Italian Renaissance, which, with a few exceptions, preferred light, luminous colours and profile positions of the protagonists’ faces, all the greatest masters devoted themselves to portraits, from Raffaello to Leonardo da Vinci, whose Mona Lisa is a timeless pictorial icon, and from Sandro Botticelli to Piero della Francesca, whose Double Portrait of the Dukes of Urbino still fascinates fans all over the world.

The static poses and the focus on faces alone began to be overcome in the artistic periods of the Baroque and Rococo in which painters began not only to interpret the inner expression of their subjects but also the moment of the body’s action, such as raising a hand in the moment of dialogue, and also emphasising the opulence and richness of the clothes of the gentlemen immortalised; Pieter Paul Rubens, Rembrandt, Gian Lorenzo Bernini were the greatest representatives of these two styles. With Realism, on the other hand, portraits lost their initial function as pictorial photographs of the nobility or of the new lords of the bourgeoisie, as the artists’ interest shifted to ordinary people, to the humblest workers, their sufferings in life, the tiring routine of everyday life and the struggles to obtain greater rights; with the arrival of the twentieth century, however, there was a return to the portrayal of the faces of lords and bourgeoisie and then, with the approach of the 1950s, also of the new film icons. From Gustav Klimt to Egon Schiele, from Picasso to Modigliani, from Tamara de Lempicka to Andy Warhol, they all played a major role in highlighting faces that gained notoriety through their artistic production. Norwegian painter Zoja Sperstad takes up the theme of the portrait in its most traditional sense, immortalising contemporary noblemen in all their royalty and elegance but also revealing their true colours, the more emotional ones which, thanks to the artist’s eye and descriptive skill, are also revealed to the observer.

Her style is Expressionist, due to the use of a range of colours that is often unreal and linked more to the personality and typical characteristics of the characters she portrays than to the palaces and gardens in which she places her protagonists; but she also has the characteristics of Magic Realism due to the tendency to portray her subjects as if they were suspended, enveloped in a dreamy atmosphere, immersed in the surrounding nature that perfectly matches their serene and enchanted state of mind. She immortalises the nobles who revolve around Villa Cesarina in Valganna, which she frequents periodically, owned by the Duke of Valganna but open to events in which art and culture are the protagonists; the enchanted setting in which the palace is located acts as a co-protagonist for many of the artworks in which the elegant but multi-faceted personalities of the women and men who belong to the family or that revolve around it, allowing Zoja Sperstad to bring out the expressive peculiarities, the approach to life that each of them, in their multifaceted individuality, demonstrates. Violetta canvas is dedicated to the international artistic gymnastics champion and choreographer Violetta Ballirano, who is portrayed doing what she loves to do most, that is harmonising her body to music, to the connection between precision of execution and emotionality that distinguishes disciplines that are strict and yet incredibly soft in their bodily expression. Sperstad describes her poetically immersed in nature in front of a view of Villa Cesarina, a place that the gymnast frequents and where she often has the opportunity to perform.

The perfection of her movement is portrayed through her body, while her concentration and joy in performing are described by her gaze, her confident yet satisfied expression as she does what she loves. The painting Famiglia di Villa Cesarina, on the other hand, is dedicated, in the most classic manner, to the family portrait, that of immortalising the members of a noble dynasty who have survived the contemporary world and are able to make a contribution by opening the doors of their home to promote fashion, art, literature, music, everything that is able to lift the spirits and shift the attention towards something that is able to distract from everyday reality while at the same time spreading culture; in this canvas, the poses of the characters depicted are more traditional, almost Rococo in style due to the fact that they are portrayed in the full knowledge that they are being portrayed, choosing the most appropriate movement or attitude for what they want to express to the observer, looking directly and confidently at the artist as if they were in front of a photographer’s lens. Her adherence to Magic Realism, however, pushes her to suspend the place and placement in the space surrounding the characters, to mix the scenes as if each of them carried with them their own emotional world, the place where they preferred to stay, because what really counts is the atmosphere surrounding the building, both outside and inside.

Zoja Sperstad’s love for the fairy-tale setting of the Duke of Valganna’s family emerges even more clearly in the painting Villa Cesarina, in which the dwelling becomes the absolute protagonist of the canvas, with its light and luminous tones, surrounded by nature that cannot fail to become a frame within which the artist places the Duke and his wife in their most official guise, in their most solemn but also serene expression due to the pleasure of being immersed in such a welcoming setting. In The creators of masterpieces, the artist abandons noble portraiture and shifts to more universal atmospheres, more oriented towards highlighting the relationship between human beings and nature through beauty, the perfection of one in relation to the other, describing the woman as wrapped in a protective cocoon in which nudity represents the need to look inside oneself and at the same time protect a fragile, delicate interiority, which is nurtured by nature, understood as naturalness. Zoja Sperstad tells of a suspended world, once again decontextualising the protagonist of the canvas to place her in an ideal place, that of the soul, within which contemporary man often wishes to hide in order to cultivate what is lost in everyday life. Zoja Sperstad has had many solo exhibitions in Norway, Russia, Italy and France, and her artworks have been shown in group exhibitions in Paris, Venice, Pesaro, Milan, Tbilisi (Georgia), Finland, Norway and Russia. She also collaborates in the organisation of art and cultural events at Villa Cesarina in Valganna.