La capacità di rappresentare la realtà così come osservata, con tutte le sfumature e i dettagli che la definiscono, a volte si limita a una narrazione estetica, formale, di ciò che è senza che subentrino capacità interpretative dell’artista, altre invece l’esecutore dell’opera diviene mezzo di osservazione, filtro emozionale attraverso il quale il fruitore riceve le vibrazioni e le sensazioni che dall’opera fuoriescono. La pittrice di cui vi racconterò oggi rivela una particolare sensibilità in virtù della quale riesce a infondere alle sue tele una singolare atmosfera, un manto emotivo in virtù del quale i suoi personaggi comunicano, oltre che a essere descritti.

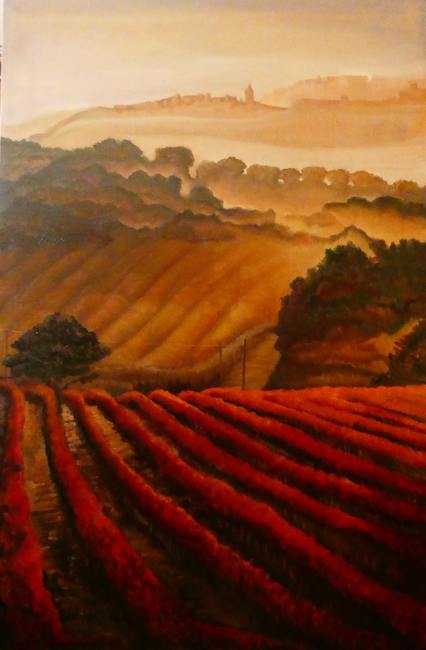

Molto spesso il Realismo è stato accusato, dalle correnti artistiche di fine Ottocento e di quelle di inizi Novecento, di freddezza, di puro racconto estetico da cui non trapelava l’interiorità dell’artista bensì era semplicemente una riproduzione fedele di ciò che il suo sguardo coglieva, senza far avvertire il proprio pensiero, la sensazione percepita davanti ai personaggi che posavano o quelli le cui azioni ne catturavano lo sguardo inducendolo poi a riprodurne le gesta. Soprattutto nel tema del ritratto non vi era una vicinanza tra soggetto e artista, piuttosto sembrava esservi una sorta di distacco emotivo perché ciò che doveva prevalere era la forma. Con l’affermarsi dell’Espressionismo e di tutti i movimenti del Novecento, l’aderenza alla realtà perse lentamente il suo ruolo predominante al punto di essere completamente sostituita dal mondo intenso delle emozioni, nel caso dell’Espressionismo, dei sogni e degli incubi, come nel Surrealismo, dalla scomposizione formale costituente punti di vista differenti e contemporanei di ciò che l’occhio osservava, come nel caso del Cubismo, o con la negazione completa della forma che invece era obiettivo e scopo principale dell’Astrattismo e di tutto ciò che da esso derivò. Tuttavia i volti e le scene di vita quotidiana immortalati da maestri del Realismo lasciavano trapelare non l’interpretazione degli artisti bensì le emozioni e i pensieri oggettivi dei protagonisti raccontati, svelando di fatto una modalità di osservazione più orientata all’ascolto che non al dialogo; con il proseguire del Ventesimo secolo furono diverse le correnti pittoriche che vollero mantenere il contatto con l’oggettività, con la forma estetica, e che rifiutarono dunque le considerazioni degli avanguardisti dimostrando con le loro opere quanto l’immagine formalmente armonica potesse invece lasciar trasparire emozioni e sensazioni malgrado l’apparente perfezione. Negli Stati Uniti il Realismo Americano mostrò un approccio fortemente emozionale e psicologico, a dispetto di una fedele riproduzione dei paesaggi e delle scene raffigurate, in virtù del quale emergeva il disagio e la solitudine dell’essere umano degli anni Cinquanta, le sue condizioni di vita spesso indigenti e difficoltose, e il senso di vuoto che trapelava dagli sguardi dei personaggi ritratti; Edward Hopper con le sue immagini della classe media statunitense, quell’apparente bel vivere accompagnato spesso da un profondo senso di isolamento, dimostrò quanto il nuovo approccio al Realismo potesse essere impregnato di emotività e di esplorazione interiore. La pittrice bolognese Carla Patella, in arte Karlotta, prende il tema del ritratto e lo avvolge di atmosfere che rivelano la sua inclinazione empatica, quel porsi in dialogo in cui però la parte dell’ascolto è prioritaria, riuscendo così a manifestare in maniera figurativa tutto ciò che all’interno della mente e dello sguardo si muove, spesso persino in maniera inconscia.

Il bello può anche non escludere la profondità, sembra suggerire l’artista, tutto ciò che colpisce lo sguardo per forma esteriore ha una sua essenza più intima, più solida rispetto all’apparenza prevalente; i suoi personaggi sono colti in frangenti riservati, quelli durante i quali è più facile mettersi in contatto con il proprio io interiore, la parte più fragile che per questo viene protetta e tutelata, che però davanti allo sguardo avvolgente della Patella emerge e si racconta all’osservatore. Il suo stile è indubbiamente Realista senza tuttavia presentare il distacco dal soggetto raffigurato, tutt’altro, l’artista compartecipa, comprende, accoglie, le sensazioni e le emozioni e le amplificando e indagando la personalità dei protagonisti e le sue sfaccettature per esplicitarle, per diffonderle all’interno della tela.

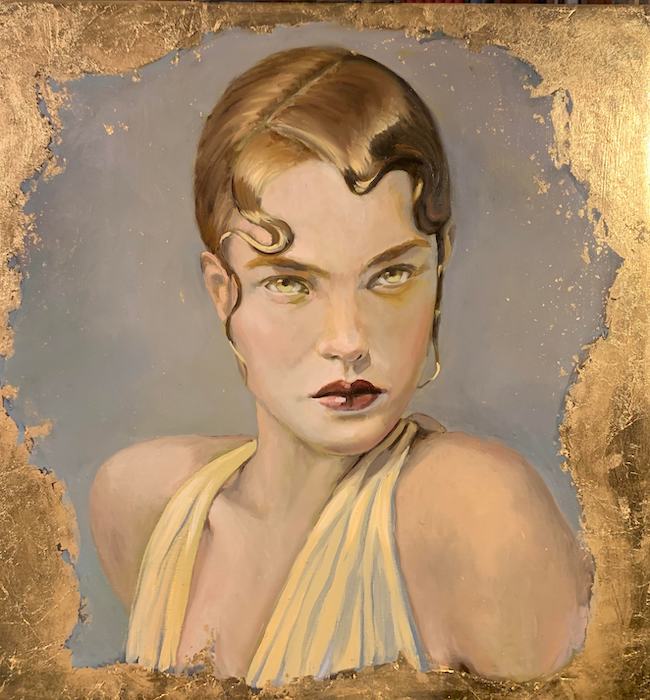

In Polvere di stelle (Stardust) Carla Patella racconta di un’epoca lontana eppure divertente, quella degli Anni Venti, periodo a cavallo tra i due conflitti mondiali durante il quale la gioia di vivere era imperativo e dove la ricerca della bellezza faceva parte di una nuova quotidianità, di un rinnovato senso di sollievo per il ritorno alla pace accompagnato all’inedita consapevolezza di dover approfittare dei doni della vita proprio in virtù del rischio appena passato di perderli; la donna osserva intensamente il fruitore, quasi a sfidarlo a sottrarsi al suo fascino, conscia di quanto l’estetica costituisse e costituisca un elemento importante nella società di allora quanto in quella odierna, forse persino fin troppo attenta alla forma. Il richiamo al passato costituisce un parallelismo con l’attualità rendendo così la tela intensa e attuale.

Nel dipinto L’indecisione di Jolie, l’espressione della protagonista è di dubbio ma anche di meditazione, sembra essere sul punto di fare qualcosa per cui al tempo stesso è trattenuta, come se da quell’azione potessero dipanarsi una serie di reazioni che non è certa di essere in grado di sostenere; i pensieri si manifestano sulla tela grazie alla sensibilità interpretativa della Patella che non giudica, non lo fa mai, semplicemente racconta ciò che il suo sguardo osserva e la sua interiorità riceve. C’è timidezza nello sguardo della ragazza, ma anche spregiudicatezza, determinazione mista a insicurezza, malizia e candore, aspetti contrastanti magistralmente rivelati dall’artista che compartecipa ed esalta le sfaccettature del personaggio raccontato.

In Ti regalerò la rosa la donna si volta come se la sua attenzione fosse stata attratta da una voce, da una persona, forse un uomo, che cerca di trattenerla, di non lasciarla andar via malgrado la sua intenzione di allontanarsi; l’espressione del volto è malinconica e dolce al tempo stesso, quasi a sottolineare una reazione suscitata da un comportamento, da un gesto, da una parola, che hanno provocato in lei una delusione, la disillusione nei confronti di un’aspettativa forse troppo alta. È questo il senso di quella rosa, quell’azione volta a recuperare ciò che è appena stato perduto, a far tornare il sorriso sul volto della donna e cancellare la tristezza che vela il suo sguardo.

Nell’opera La noia, Carla Patella pone l’accento sull’apatia che spesso avvolge l’esistenza contemporanea a causa della consapevolezza di poter avere tutto senza sforzo, un approccio che genera a lungo andare la sensazione che qualsiasi azione, qualunque circostanza, non stimoli l’entusiasmo della conquista, del dover fare uno sforzo per ottenere un risultato o un momento di svago. Nella società dell’immagine dove tutto prevale sulla sostanza, l’imperativo è di rendere prioritaria un’apparenza, una vacuità che non può fare a meno di generare un vuoto interiore che a lungo andare si trasforma in noia, più verso se stessi che non verso ciò che si sta facendo; l’incapacità di emozionarsi per le piccole cose è il limite maggiore dell’uomo contemporaneo che si trova disorientato a non provare emozione per nulla che non sia l’inseguimento di quell’apparire ormai divenuto l’essenza stessa della società.

Carla Patella ha all’attivo la partecipazione a molte mostre collettive su tutto il territorio nazionale, una personale a Bologna nell’anno 2006 e le sue opere sono inserite in numerosi cataloghi e riviste d’arte.

CARLA PATELLA-CONTATTI

Email: karlotta.pat@gmail.com

Sito web: www.carlapatella.it

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/carla.patella.14

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/carla_patella/

Carla Patella’s nostalgic atmospheres, between memories of the past and contemporary emotions

The ability to represent reality as it is observed, with all the nuances and details that define it, is sometimes limited to an aesthetic, formal narration of what it is without the artist’s interpretative skills, while at others the artist becomes a means of observation, an emotional filter through which the viewer receives the vibrations and sensations that emerge from the artwork. The painter I am going to tell you about today reveals a particular sensibility by virtue of which she manages to infuse her canvases with a singular atmosphere, an emotional mantle through which her characters communicate in addition of being described.

Realism has often been accused, by the artistic currents of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, of coldness, of a purely aesthetic narrative from which the artist’s interiority did not emerge, but was simply a faithful reproduction of what his gaze caught, without making his own thoughts, the sensation perceived in front of the characters posing or those whose actions caught his eye, leading him to reproduce their gestures. Especially in the subject of portraits, there was no closeness between the subject and the artist; rather, there seemed to be a kind of emotional detachment because it was the form that had to prevail. With the rise of Expressionism and all the movements of the twentieth century, adherence to reality slowly lost its predominant role to the point of being completely replaced by the intense world of emotions, in the case of Expressionism, of dreams and nightmares, as in Surrealism, by formal decomposition constituting different and contemporary points of view of what the eye observed, as in the case of Cubism, or with the complete negation of form, which instead was the main objective and aim of Abstractionism and all that derived from it. However, the faces and scenes of everyday life immortalised by the masters of Realism did not reveal the interpretation of the artists but rather the emotions and objective thoughts of the protagonists narrated, revealing a mode of observation that was more oriented towards listening than towards dialogue; as the 20th century progressed, there were several currents of painting that wished to maintain contact with objectivity, with aesthetic form, and which therefore rejected the considerations of the avant-gardists, demonstrating through their works how a formally harmonious image could instead allow emotions and feelings to shine through notwithstanding its apparent perfection.

In the United States, American Realism displayed a strongly emotional and psychological approach, despite the faithful reproduction of the landscapes and scenes depicted, by virtue of which the unease and loneliness of human beings in the 1950s emerged, their often destitute and difficult living conditions, and the sense of emptiness that leaked from the gazes of the characters portrayed; Edward Hopper, with his images of the American middle class, that apparent good life often accompanied by a profound sense of isolation, demonstrated how the new approach to Realism could be imbued with emotionality and inner exploration. Bolognese painter Carla Patella, aka Karlotta, takes the theme of the portrait and wraps it in atmospheres that reveal her empathic inclination, that dialogue in which, however, the listening part takes priority, thus succeeding in figuratively manifesting everything that moves within the mind and the gaze, often even in an unconscious manner. Beauty may not exclude depth, the artist seems to suggest; everything that strikes the eye through its external form has its own more intimate essence, more solid than the prevailing appearance; her characters are captured in reserved moments, those during which it is easier to get in touch with one’s inner self, the most fragile part which is therefore protected and safeguarded, but which in front of Patella’s enveloping gaze emerges and tells itself to the observer.

Her style is undoubtedly Realist without, however, presenting a detachment from the depicted subject, quite the contrary, the artist shares, understands, welcomes, the sensations and emotions and amplifies and investigates the personality of the protagonists and its facets to make them explicit, to spread them within the canvas. In Stardust, Carla Patella recounts a distant yet amusing epoch, that of the 1920s, a period between the two world wars during which the joy of living was imperative and where the search for beauty was part of a new everyday life, of a renewed sense of relief at the return to peace accompanied by the unprecedented awareness of having to take advantage of life’s gifts precisely by virtue of the risk just passed of losing them; the woman observes the viewer intensely, almost as if to challenge him to escape her fascination, aware of how aesthetics were and are an important element in the society of the time as well as in today’s society, which is perhaps even too concerned with form. The reference to the past constitutes a parallel with the present, making the canvas intense and topical. In the painting L’indecisione di Jolie (Jolie’s indecision), the protagonist’s expression is that of doubt but also of meditation; she seems to be on the point of doing something, but at the same time she is restrained, as if a series of reactions that she is not sure she can withstand could unravel from that action; her thoughts manifest themselves on the canvas thanks to Patella’s interpretative sensitivity; she never judges, she simply recounts what her gaze observes and her interiority receives. There is shyness in the girl’s gaze, but also unscrupulousness, determination mixed with insecurity, malice and candour, contrasting aspects masterfully revealed by the artist, who shares and enhances the facets of the character she tells. In Ti regalerò la rosa (I will give you the rose) the woman turns as if her attention has been attracted by a voice, by a person, perhaps a man, who is trying to hold her back, not to let her go despite her intention to leave.

The expression on her face is both melancholic and sweet, as to underline a reaction provoked by a behaviour, a gesture, a word, which has caused her disappointment, disillusionment of an expectation that was perhaps was too high. This is the meaning of that rose, that action aimed at recovering what has just been lost, at bringing a smile back to the woman’s face and erasing the sadness that veils her gaze. In her painting La noia (Boredom), Carla Patella emphasises the apathy that often envelops contemporary existence due to the awareness of being able to have everything without effort, an approach that in the long run generates the feeling that any action, any circumstance, does not stimulate the enthusiasm of conquest, of having to make an effort to obtain a result or a moment of leisure. In the society of the image, where everything prevails over the substance, the imperative is to give priority to an appearance, a vacuity that cannot help but generate an inner emptiness that in the long run turns into boredom, more towards oneself than towards what one is doing; the inability to be moved by small things is the greatest limitation of contemporary man, who finds himself disoriented and unable to feel emotion for anything other than the pursuit of that appearance which has now become the very essence of society. Carla Patella has taken part in many group exhibitions throughout Italy, including a solo exhibition in Bologna in 2006, and her artworks have been included in numerous catalogues and art magazines.