L’arte ha la caratteristica di rivelare il tipo di sguardo con cui ciascun creativo si pone nei confronti della vita, di quale sia la direzione verso cui egli si orienta e quali siano le linee guida su cui muove non solo i suoi passi esistenziali bensì anche quelli espressivi; lo stile dunque si conforma alla personalità e all’intento dell’esecutore dell’opera svelando quanto egli sia più predisposto all’osservazione puramente emozionale della contemporaneità, oppure quanto sia proiettato alla lucida analisi del presente, o ancora quanto abbia bisogno di restare nostalgicamente attaccato a un passato distante eppure pieno di attrattiva che sembra quasi essere un modo per allontanarsi da una dimensione attuale che si è spinta in una direzione completamente divergente da quella sperata. La protagonista di oggi appartiene a quest’ultima categoria di artisti e con un tocco pittorico poetico e ricercato mostra differenti sfaccettature di una femminilità senza tempo.

Tra la fine dell’Ottocento e gli inizi del Novecento si sviluppò nell’intero continente europeo uno stile in cui la bellezza, il fasto, l’eleganza, erano denominatori comuni e linee guida imprescindibili, e dove l’equilibrio estetico doveva essere accompagnato dalla delicatezza delle decorazioni floreali; questo stile prese un nome diverso sulla base del paese da cui provenivano gli artisti, dunque si chiamò Stile Liberty in Italia, Art Nouveau in Francia e in Belgio, Secessione Viennese in Austria e nell’impero austro-ungarico e Modernismo in Spagna. Le linee morbide, la presenza di elementi di rami, foglie e fiori che facevano da cornice alle bellissime figure femminili rappresentate con innocenza ammaliante, erano caratteristiche peculiari del movimento, così come l’estensione di questi princìpi a molti settori figurativi come l’architettura, le decorazioni, l’oggettistica, trasformando così quel gusto estetico in uno stile di vita. In particolar modo nella Secessione Viennese emerse anche un largo uso della foglia oro, simbolo di opulenza e di sfarzosità, che è riscontrabile nel celeberrimo periodo aureo di Gustav Klimt. Il sopraggiungere della prima guerra mondiale determinò però la prematura fine di quel periodo di benessere e di desiderio di bellezza, costringendo molti artisti ad andare in guerra e a osservare la distruzione che ne seguì, determinando così un’inversione di tendenza e l’affermarsi di un altro movimento, l’Espressionismo, dove tutte le regole e l’attenzione all’estetica furono messi in disparte in favore di un apparato figurativo che si adeguasse ai tormenti interiori e al mondo delle emozioni. Dopo la fine del conflitto vi fu però anche un ritorno all’ottimismo, una rinnovata fiducia nel futuro, la possibilità di assaporare la vita essendo grati di essere sopravvissuti e questo si tradusse, dal punto di vista stilistico con quella che può essere considerata un’evoluzione dell’Art Nouveau, una rivisitazione in cui l’eleganza, la raffinatezza e la bellezza si spogliarono della frivolezza rappresentativa dell’elemento floreale, le linee divennero meno tondeggianti e più squadrate mentre venne mantenuta l’opulenza della foglia oro e la classe indiscussa che gli edifici, le decorazioni e gli accessori appartenenti all’Art Déco, mostrarono al mondo. Fu in questo contesto che si distinse l’opera pittorica, quasi unica in realtà, dell’artista polacca Tamara de Lempicka le cui donne stilose e affascinanti lasciarono un’importante testimonianza del gusto di quell’epoca e dell’attenzione al lusso e alla ricercatezza. Kinga Łapot-Dzierwa ha in comune con la grande interprete dell’Art Déco del secolo scorso non solo la nazionalità polacca, ma anche l’attenzione al mondo femminile attraverso il quale esprime il suo punto di vista, il suo desiderio di mantenere un profondo legame con il buongusto estetico che sembra essere scomparso nel vivere contemporaneo, un’attenzione alla signorilità che comprende anche la capacità di vestirsi ponendo attenzione ai dettagli, ai particolari che vengono accompagnati da gesti morbidi, moderati come alle signorine d’altri tempi veniva insegnato.

Laddove la de Lempicka rappresentava un mondo nuovo, una rinascita dopo le atrocità della guerra, la Łapot-Dzierwa invece racconta con sguardo nostalgico un passato in cui la donna era tenuta su un più alto livello di considerazione, e malgrado non avesse acquisito tutti i diritti conquistati con le lotte sociali e femministe della seconda metà del Novecento, in ogni caso era ammirata e profondamente rispettata dal mondo maschile anche per il suo atteggiamento composto e moderato.

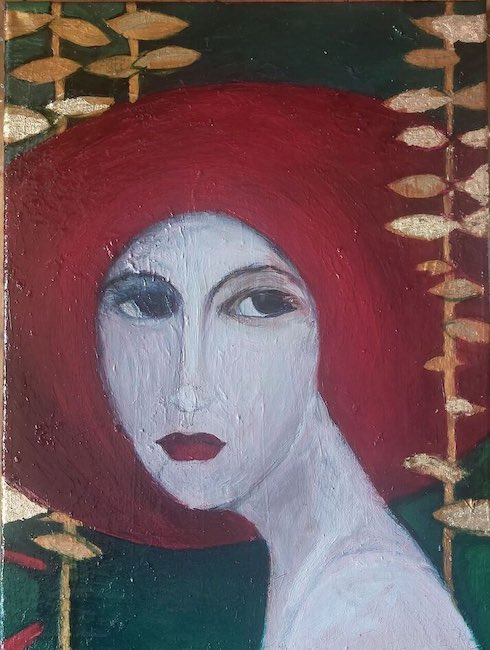

Questo è ciò che esprimono le donne raccontate da Kinga Łapot-Dzierwa, quel manierismo di grande classe accompagnato spesso da uno sguardo malinconico, lontano, come se le sue protagoniste desiderassero sempre di trovarsi in un altro luogo e si stupissero di essere immortalate in un’opera d’arte, mostrando un senso di straniamento che le fa apparire vicine all’osservatore ma al tempo stesso lontane, perse nel loro mondo emozionale.

Dal punto di vista stilistico Kinga Łapot-Dzierwa non si limita a rielaborare e personalizzare le tematiche Art Déco bensì introduce anche elementi riconducibili ad altre cifre pittoriche come una vicinanza all’Espressionismo di Amedeo Modigliani, che si manifesta con i colli allungati delle sue figure femminili e la forma del volto ispirato alle maschere indigene tipiche del Primitivismo a cui il maestro italiano si ispirò; d’altro canto gli sguardi persi e quasi ipnotici non possono non ricondurre, almeno nell’intenzione espressiva, a quel Realismo Magico in cui il senso di straniamento era ciò che colpiva in maniera travolgente l’attenzione dell’osservatore.

Le pose delle donne sono però quasi frivole, ricordano i ritratti delle nobildonne eseguiti dai grandi rappresentanti dell’Impressionismo, come se quel gusto retrò non dovesse essere mai perduto perché simbolo di una femminilità marcata e consapevole. Nella tela Woman with red hat 1, Kinga Łapot-Dzierwa racconta di una donna sicura e distaccata, ma forse anche essenzialmente timida al punto di nascondere una parte del suo volto sotto la tesa del cappello, irrinunciabilmente rosso come l’intera serie pittorica dedicata al mondo femminile; la presenza delle farfalle azzurre sottolinea la predisposizione al sogno, a un desiderio di poter volare verso un luogo lontano, più vicino a ciò che la protagonista desidera diventare. La durezza dello sguardo e la determinazione svelata dalla scelta del rosso per il cappello e per l’abbigliamento, sembrano dunque ammorbiditi dalla presenza di quei leggerissimi animali che sembrano evocare la necessità di lasciarsi andare, di abbandonare l’apparente rigidità e abbandonarsi alla possibilità di realizzare un desiderio segreto.

In Smoking a cigarette la donna sembra essere colta di sorpresa, chiamata da qualcuno che si trovava nello stesso punto da cui Kinga Łapot-Dzierwa l’ha osservata, e dunque si volta senza smettere di compiere il gesto rilassato di tenere in mano la sigaretta sostenuta da un lungo bocchino, come era d’abitudine negli anni Venti e Trenta del secolo scorso; in quest’opera l’eleganza è persino più sottolineata, l’opulenza è enfatizzata dalla presenza della foglia oro nello sfondo, a riprodurre lo sfarzo dei salotti aristocratici evocati nei romanzi di Francis Scott Fitzgerald e in grado di suscitare uno sguardo nostalgico nell’osservatore, come se fosse irresistibile il desiderio di immaginarsi protagonisti delle atmosfere raccontate dall’autrice dell’opera.

Il colore rosso dunque costituisce l’elemento energetico, suggerisce la sicurezza in se stesse delle figure femminili immortalate, consapevoli di essere una parte importante ed emblematica della società dell’epoca e dunque forse l’invito di Kinga Łapot-Dzierwa alle donne moderne è quello di recuperare la propria femminilità, di ricordarsi che essere eleganti e aggraziate non significa rinunciare all’emancipazione e all’indipendenza faticosamente conquistate, bensì la sfida è quella di riuscire a farle convivere mantenendo il misterioso fascino che da sempre è appartenuto all’universo femmineo.

Anche nelle opere in cui lascia parlare i fiori l’artista non rinuncia all’energia del rosso, infatti dedica un’intera serie ai papaveri intitolata Polish flowers, Poppies in cui sceglie degli sfondi prevalentemente scuri ma anche azzurri con elementi tendenti al bianco ghiaccio, come nella tela Poppies 3, proprio per evidenziare la loro forza a dispetto dell’apparente delicatezza, metafora dell’essenza della femminilità. Kinga Łapot-Dzierwa, educatrice artistica e professoressa presso la Facoltà di Arte dell’Università della Commissione per l’Educazione Nazionale di Cracovia, nel corso della sua carriera ha vinto numerosi e prestigiosi premi d’arte, le sue opere sono regolarmente battute nelle case d’asta e ha partecipato a mostre collettive e personali in tutto il mondo – Italia, Spagna, USA, Ucraina, Germania, Romania, Thailandia, Svezia, Slovacchia, e ovviamente, Polonia -.

KINGA ŁAPOT-DZIERWA-CONTATTI

Email: kdzierwa@op.pl

Facebook: www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100001100395710

Instagram: www.instagram.com/lapotdzierwa/

Linkedin: www.linkedin.com/in/kinga-%C5%82apot-dzierwa-31477169/

The Art Deco women by Kinga Łapot-Dzierwa, between the passion of red and the elegant refinement of a timeless style

Art has the characteristic of revealing the kind of outlook with which each creative approaches life, what direction is heading in and what are the guidelines on which he moves not only his existential steps but also his expressive ones; the style, therefore, conforms to the personality and intent of the work’s executor, showing how much he is more inclined to a purely emotional observation of contemporaneity, or how much he is projected towards a lucid analysis of the present, or how much he needs to remain nostalgically attached to a distant yet attractive past that seems almost to be a way of distancing from a current dimension that has moved in a completely divergent direction from the one he had hoped for. Today’s protagonist belongs to the latter category of artists and with a poetic and refined pictorial touch shows different facets of a timeless femininity.

Between the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century, developed a style across the entire European continent in which beauty, splendour and elegance were common denominators and inescapable guidelines, and in which aesthetic balance had to be accompanied by the delicacy of floral decorations; this style took on a different name depending on the country the artists came from, so it was called Stile Liberty in Italy, Art Nouveau in France and Belgium, Viennese Secession in Austria and the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and Modernism in Spain. The soft lines, the presence of elements of branches, leaves and flowers that framed the beautiful female figures depicted with bewitching innocence, were peculiar features of the movement, as was the extension of these principles to many figurative fields such as architecture, decoration, and objects, thus transforming that aesthetic taste into a lifestyle.

Particularly in the Viennese Secession there also emerged a widespread use of gold leaf, a symbol of opulence and sumptuousness, which can be seen in Gustav Klimt‘s celebrated Golden Age. The coming of the First World War, however, brought an untimely end to that period of prosperity and desire for beauty, forcing many artists to go to war and observe the destruction that followed, leading to a reversal and the rise of another movement, Expressionism, where all rules and attention to aesthetics were sidelined in favour of a figurative apparatus that was in tune with inner torments and the world of the emotions. After the end of the conflict, however, there was also a return to optimism, a renewed faith in the future, the possibility of savouring life while being thankful for having survived, and this translated stylistically into what can be considered an evolution of Art Nouveau, a reinterpretation in which elegance refinement and beauty were stripped of the representative frivolity of the floral element, the lines became less rounded and more squared while the opulence of gold leaf and the undisputed class that Art Deco buildings, decorations and accessories displayed to the world was retained. It was in this context that stood out the almost unique pictorial work of the Polish artist Tamara de Lempicka, whose stylish and glamorous women left an important testimony to the taste of the time and the focus on luxury and sophistication. Kinga Łapot-Dzierwa shares with the great interpreter of Art Deco of the last century not only her Polish nationality, but also the attention to the world of women through which she expresses her point of view, her desire to maintain a profound link with aesthetic good taste that seems to have disappeared in contemporary life, an attention to elegance that also includes the ability to dress with attention to detail, to particulars that are accompanied by soft, moderate gestures as the ladies of the past were taught. While de Lempicka represented a new world, a rebirth after the atrocities of the war, Łapot-Dzierwa, on the other hand, nostalgically recounts a past in which women were held in higher regard, and although they had not acquired all the rights conquered with the social and feminist struggles of the second half of the 20th century, they were in any case admired and deeply respected by the male world also for their composed and moderate attitude. This is what the women portrayed by Kinga Łapot-Dzierwa express, that mannerism of great class often accompanied by a melancholic, distant gaze, as if her protagonists always wished they were in another place and were surprised to be immortalised in an artwork, showing a sense of estrangement that makes them appear close to the observer but at the same time distant, lost in their emotional world.

From a stylistic point of view, Kinga Łapot-Dzierwa not only reworks and personalises Art Deco themes, but also introduces elements that can be traced back to other pictorial guidelines, such as a closeness to Amedeo Modigliani‘s Expressionism, which is manifested in the elongated necks of her female figures and the shape of their faces inspired by the indigenous masks typical of Primitivism, from which the Italian master drew inspiration; on the other hand, the lost and almost hypnotic gazes cannot fail to lead back, at least in their expressive intention, to that Magic Realism in which the sense of estrangement was what overwhelmingly captured the observer’s attention. The poses of the women, however, are almost frivolous, reminiscent of the portraits of noblewomen painted by the great masters of Impressionism, as if that retro taste were never to be lost because it symbolised a marked and conscious femininity. In the canvas Woman with red hat 1, Kinga Łapot-Dzierwa tells the story of a woman who is confident and detached, but perhaps also essentially shy to the point of hiding part of her face under the brim of her hat, which is unmistakably red like the entire pictorial series dedicated to the world of women. The presence of the blue butterflies emphasises the predisposition to dream, to a desire to be able to fly towards a faraway place, closer to what the protagonist wishes to become. The hardness of her gaze and the determination revealed by the choice of red for her hat and clothing thus seem to be softened by the presence of those very light animals that seem to evoke the need to let go, to abandon apparent rigidity and surrender to the possibility of realising a secret desire.

In Smoking a cigarette the woman seems to be taken by surprise, called by someone who was standing in the same spot from which Kinga Łapot-Dzierwa observed her, and so she turns without ceasing to make the relaxed gesture of holding a cigarette supported by a long mouthpiece, as was the custom in the 1920s and 1930s; in this artwork the elegance is even more emphasised, the opulence is underlined by the presence of gold leaf in the background, reproducing the sumptuousness of the aristocratic salons evoked in Francis Scott Fitzgerald‘s novels and capable of arousing a nostalgic look in the observer, as if it were an irresistible desire to imagine oneself as the protagonist of the atmospheres narrated by the author of the painting. The colour red therefore constitutes the energetic element, suggesting the self-confidence of the female figures immortalised, aware of being an important and emblematic part of the society of the time, and so perhaps Kinga Łapot-Dzierwa‘s invitation to modern women is to recover their femininity, to remind themselves that being elegant and graceful does not mean renouncing their hard-won emancipation and independence, but rather the challenge is to manage to combine them while maintaining the mysterious charm that has always belonged to the feminine universe. Even in the artworks in which she lets the flowers speak, the artist does not renounce the energy of red. In fact, she dedicates an entire series to poppies entitled Polish flowers, Poppies, in which she chooses predominantly dark backgrounds but also light blues with elements tending towards ice white, as in the painting Poppies 3, precisely to highlight their strength despite their apparent delicacy, a metaphor for the essence of femininity. Kinga Łapot-Dzierwa, an art educator and professor at the Faculty of Art at the University of the National Education Commission in Cracow, in the course of her career has won numerous prestigious art awards, her artowrks are reguarly on auction houses and participated in group and individual exhibitions all over the world – Italy, Spain, USA, Ukraine, Germany, Romania, Thailand, Sweden, Slovakia, and of course, Poland.