Il vivere contemporaneo conduce molto frequentemente gli artisti a entrare nei meandri delle difficoltà, delle ansie di un vivere costantemente all’inseguimento di obiettivi materiali, dei disagi appartenenti a un mondo moderno in cui l’individualismo sembra essere assoluto protagonista nonostante di fatto ciò che più affligge l’esistenza sia proprio la solitudine che da esso deriva; questo atteggiamento introspettivo produce opere in cui le riflessioni, le domande a cui spesso non si trova risposta, danno vita a opere in cui a emergere è proprio questo lato della realtà, questa analisi di tutto ciò che appartiene al vivere contemporaneo. Ma di contro vi sono altri tipi di creativi che hanno bisogno di astrarsi da quel tipo di osservazione per entrare in una dimensione in cui a emergere deve essere la semplicità, la leggerezza nell’affrontare tutto ciò che appartiene alla quotidianità con un approccio più sognante, come se dipingere divenisse evasione, rifugio ideale in cui manifestare le proprie emozioni positive. L’artista di cui vi racconterò oggi ha esattamente questo tipo di atteggiamento espressivo, rendendo la pittura un mezzo per raccontare la delicatezza, la spontaneità e la semplicità necessari a trovare la bellezza e la positività in ogni dettaglio dell’esistenza.

Quando a fine Ottocento cominciarono a delinearsi i primi battiti di ribellione nei confronti dell’arte accademica precedente, gli artisti che furono anticipatori delle rivoluzioni che di lì a poco si sarebbero susseguite vollero affermare con forza l’esigenza di rompere completamente gli schemi ma soprattutto di dare vita a un tipo di arte che risultasse meno formale e più sostanziale, dove l’interiorità dell’esecutore dell’opera non dovesse più rimanere in silenzio nel nome di una perferzione estetica che ormai non era più al passo con i cambiamenti che la società stava subendo. Dunque i Fauves, precursori del più esteso e diffuso Espressionismo, decisero di stravolgere letteralmente ogni regola stilistica ideando un tipo di pittura in cui non esisteva più chiaroscuro, profondità, prospettiva né tanto meno perfetta resa della realtà osservata perché la tela doveva divenire estensione delle emozioni provate, così come i colori dovevano essere affini al sentire del momento della creazione artistica. Laddove i successivi espressionisti nord europei si concentrarono sulle ansie, sulle angosce generate dai periodi bellici, sull’ipocrisia della nuova borghesia emergente e sul senso di disorientamento dell’essere umano che stava perdendo ogni certezza, i francesi invece raccolsero l’eredità di Henri Matisse, che mise principalmente in evidenza le emozioni suscitate dalle piccole cose quotidiane, dalla familiarità degli oggetti e degli ambienti domestici, e mantennero il medesimo approccio sognante e positivo, in cui l’evasione dalla realtà osservata permetteva loro di creare un mondo parallelo dentro cui astrarsi dalla contingenza e continuare a sognare. Tra i maggiori esponenti di questa sfumatura interpretativa dell’Espressionismo non si può non citare Marc Chagall, l’ingenuo e visionario artista le cui opere avevano il potere di trasportare l’osservatore nel suo mondo quasi magico, e che modificò le linee guida Fauves in delicata interpretazione di una gamma cromatica sempre accesa ma più modulata sul suo sentire poetico, delicato e sognante. L’evasione dalla realtà diviene con il maestro russo-francese un mezzo per osservare tutto con uno sguardo fanciullesco, sereno e gioioso, dove ciò che domina il suo tratto è la capacità di trovare il buono e il positivo in ogni circostanza e dove ogni evento può essere visto con occhi pragmatici oppure con quelli di un bambino, costantemente in grado di meravigliarsi e di credere che la magia si nasconda dietro ogni angolo. L’artista di origine rumena ma naturalizzata ungherese Aranka Székely in qualche modo si avvicina all’intento espressivo sognante di Chagall, perché per lei dipingere equivale a trovare uno spazio lontano dalla quotidianità in cui scrivere un racconto diverso, fatto di bei sentimenti e di frangenti indimenticabili che appartengono a giorni piacevoli e spensierati. La sua carriera di medico infatti la pone costantemente a contatto con la sofferenza umana pertanto dipingere diviene un modo per oltrepassare ciò con cui è quotidianamente a contatto e lasciar fluire invece tutto ciò che di bello la vita ha e che si armonizza molto di più alle sue inclinazioni interiori.

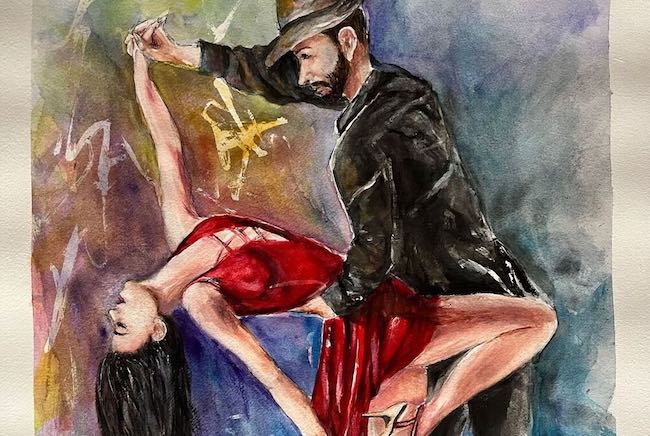

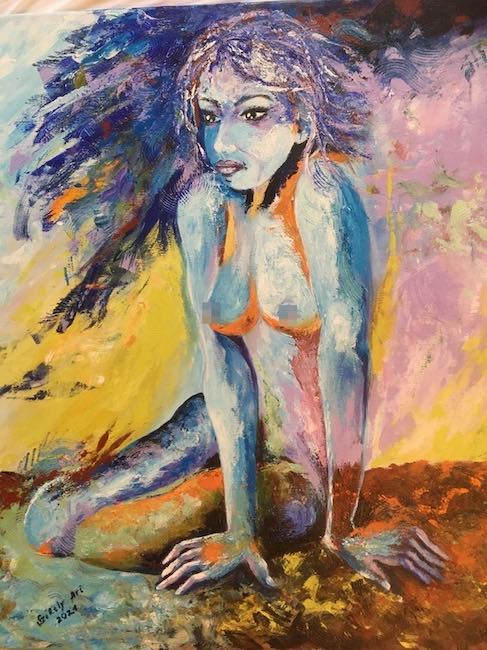

La protagonista quasi assoluta delle opere di Aranka Székely è la donna, in ogni sua sfaccettarua, dunque a volte mamma, altre amante, altre semplicemente se stessa nelle numerose sfaccettature della personalità, quasi le sue protagoniste fossero un alter ego dell’artista che di opera in opera sceglie di mettere in luce un lato di sé. Il tratto pittorico fortemente espressionista viene mitigato da una gamma cromatica a volte vicina alla realtà, altre invece più legata all’interiorità della percezione del personaggio ritratto, ma in ogni caso ciò che colpisce l’attenzione è la tendenza a sfumare molti dettagli, come lo sfondo o gli abiti, quasi a generare un’atmosfera irreale per sottolineare l’appartenenza al mondo parallelo della creazione artistica.

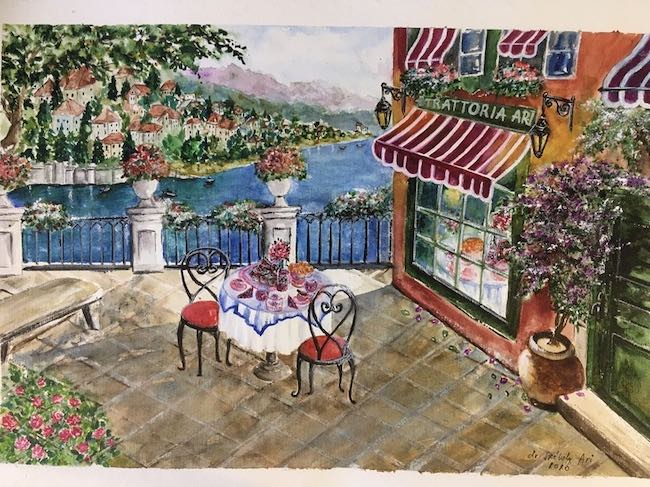

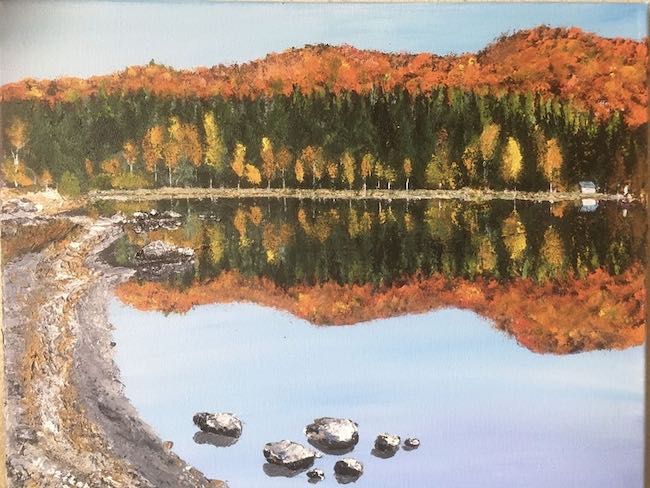

Altri particolari invece vengono evidenziati con colori pieni, molto affini a quelli reali, forse per permettere all’osservatore di concentrarsi sul messaggio che quei volti, quegli abbracci, quel volteggiare sulla pista da ballo, emanano in virtù di quel processo liberatorio che compie la Székely ogni qualvolta di pone di fronte alla tela e comincia a sognare quel mondo parallelo in cui tutto è più semplice e immediato. Anche quando descrive i paesaggi l’artista lo fa in modo sognante, come se quei ricordi, quei frammenti di vita costituissero un’evasione verso una circostanza o un frangente in il suo sguardo si è perso dentro istanti irripetibili; nel caso dei panorami i dettagli dell’intera composizione sono più specifici, più attinenti a ciò che i suoi occhi hanno visto, sebbene non manchi mai la sensazione di immergersi in un sogno, in un’atmosfera incantata dove tutto è al suo posto perché il cuore ne ha colto ogni piccolo particolare.

In Italian idyll infatti, Aranka Székely descrive uno scorcio di una cittadina sul mare italiana, dove probabilmente ha trascorso momenti indimenticabili e spensierati che l’hanno condotta a desiderare di imprimere sulla tela la bellezza che ha avuto davanti agli occhi in quel frangente. Nella serie Fairy sottolinea invece quanto la femminilità possa essere magica, possa ricondurre al mondo delle fiabe dove il positivo, il lato buono è affidato alle mani delle fate in grado di proteggere con la loro aura e di mettere al sicuro da tutto ciò che costituisce una minaccia; in fondo questi personaggi fantastici sono la metafora della figura femminea, di quel misto tra delicatezza, sensibilità, intuizione e accoglienza che contraddistingue per natura la donna.

In Autumn Fairy ciò che predomina è il leggero vento, i colori tendenti all’arancio e al giallo delle foglie malgrado lo sfondo sia decontestualizzato, come se intorno a sé la ragazza avesse solo la magia del suo potere soprannaturale; il suo volto è serio ma al contempo sereno, come se emanasse un’energia positiva quasi inconsapevole, evidenziata dal suo non rivolgere lo sguardo all’osservatore.

Allo stesso modo Winter Fairy affronta serena il freddo della stagione che rappresenta, e tradotta in termini cromatici con le tonalità degli azzurri e dei bianchi, con una leggerezza soave, quasi a voler contrastare il gelo esterno suggerendo che il calore resta costante all’interno di sé; è un’invito a danzare all’interno di quel mondo paralizzato dal freddo senza lasciarsi modificare l’atmosfera interiore. Anche in questa tela lo sfondo è dissolto, tende verso l’Astratto per mettere in evidenza le sensazioni delle donne, quell’emozionalità che permette loro di trovarsi a proprio agio in qualunque ambiente perché in perfetto equilibrio con se stesse. Sembra essere un’invito a ogni donna a trovare la medesima sicurezza, la stessa tranquillità che permette a quelle fate di non essere influenzate dall’esterno proprio perché il bilanciamento tra il positivo e il negativo che appartiene all’essere umano riesce a rendere ogni difficoltà superabile.

In Waiting for him dunque, la ragazza si sente messa a nudo nei suoi sentimenti, attende con trepidazione l’arrivo dell’amato evocato dal titolo, di cui però non è certa e pertanto sembra rimanere sospesa nella fase dell’aspettativa, su un filo che la lascia incapace di muoversi nel timore che qualunque azione possa cambiare il corso degli eventi; la sensazione di incertezza emerge dall’espressione del volto, tanto quanto l’inquietudine traspare dallo sfondo che da un lato si tinge dei colori chiari del rosa e del giallo che rappresentano il sogno d’amore, ma dall’altro viene contaminato dal blu scuro che sembra evocare il timore che il suo desiderio non si realizzi.

Aranka Székely ha coltivato da sempre il suo lato artistico parallelamente alla sua professione medica; ha al suo attivo mostre personali e collettive a Budapest, Zagabria, Roma, Firenze, Zurigo, Milano, Barcellona, New York, Venezia, Basilea, Fuerteventura, Lisbona, San Diego, Parigi, Montreux, solo per citare le più importanti, ha ricevuto numerosi premi d’arte e le sue opere sono inserite in molti annuari d’arte contemporanea.

ARANKA SZÉKELY-CONTATTI

Email: arankadr@gmail.com

Facebook: www.facebook.com/aranka.szekely.5

Instagram: www.instagram.com/arankaszekely/

The Expressionism by Aranka Székely, to observe the thousand shades of the lightness of life

Contemporary life very often leads artists to enter into the meanders of difficulties, of the anxieties of a life constantly in pursuit of material objectives, of the discomforts of a modern world in which individualism seems to be the absolute protagonist, despite the fact that what most afflicts existence is precisely the loneliness that derives from it. This introspective attitude produces reflections, questions that are often not answered, giving rise to artworks in which emerges this side of reality, this analysis of everything that belongs to contemporary life. But on the other hand, there are other types of creatives who need to abstract themselves from that type of observation in order to enter a dimension in which must emerge simplicity, lightness in facing everyday life, showing a more dreamy approach, as if painting became an escape, an ideal refuge in which to manifest their positive emotions. The artist I am going to tell you about today has exactly this kind of expressive attitude, making painting a means of conveying the delicacy, spontaneity and simplicity necessary to find beauty and positivity in every detail of existence.

When, at the end of the 19th century, began to emerge the first beats of rebellion against the previous academic art, the artists who were the forerunners of the revolutions that were to follow shortly afterwards wanted to forcefully affirm the need to completely break the mould but above all to give life to a type of art that was less formal and more substantial, where the interiority of the executor of the artwork no longer had to remain silent in the name of an aesthetic perfection that was no more in step with the changes that society was undergoing. Thus the Fauves, forerunners of the more widespread Expressionism, decided to literally overturn every stylistic rule by devising a type of painting in which there was no chiaroscuro, depth, perspective or even the perfect rendering of observed reality because the canvas had to become an extension of the emotions felt, just as the colours had to be harmonised with the feeling of the moment of artistic creation. Whereas the later Northern European Expressionists focused on the anxieties, anxieties generated by wartime, the hypocrisy of the newly emerging bourgeoisie and the sense of disorientation of the human being who was losing all certainty, the French took up the legacy of Henri Matisse, who mainly emphasised the emotions aroused by small everyday things and the familiarity of objects and domestic environments, maintaining the same dreamy and positive approach, in which evasion from observed reality allowed them to create a parallel world within which to abstract themselves from contingency and to continue dreaming.

Among the greatest exponents of this interpretative nuance of Expressionism, one cannot fail to mention Marc Chagall, the naive and visionary artist whose artworks had the power to transport the observer into his almost magical world, and who modified the Fauves guidelines into a delicate interpretation of a chromatic range that was always bright but more modulated to his poetic and delicate feeling. The escape from reality became with the Russian-French master a means of observing everything with a childlike, serene and joyful gaze, where what dominated his strokes was the ability to find the good and the positive in every circumstance and where every event could be seen with pragmatic eyes or with those of a child, constantly able to marvel and believe that magic lurks around every corner. The Romanian-born but naturalised Hungarian artist Aranka Székely is in some ways close to Chagall‘s dreamy expressive intentions, because for her, painting means finding a space away from everyday life in which to write a different story, made up of beautiful feelings and unforgettable moments that belong to pleasant and carefree days. In fact, her career as a doctor puts her constantly in contact with human suffering, so painting becomes a way of going beyond what is daily in front of her and instead letting flow all that is beautiful in life and that is much more in tune with her inner inclinations. The almost absolute protagonist of Aranka Székely‘s works is the woman, in all her facets, so sometimes a mother, sometimes a lover, sometimes simply herself in the many facets of her personality, almost as if her protagonists were an alter ego of the artist who from work to work chooses to highlight a side of her personality. The strongly expressionist pictorial stroke is mitigated by a chromatic range that is sometimes close to reality, at others more linked to the interiority of the perception of the character portrayed, but in any case what strikes the eye is the tendency to blur many details, such as the background or the clothes, almost as if to generate an unreal atmosphere to emphasise the belonging to the parallel world of artistic creation. Other details, on the other hand, are highlighted with solid colours, very close to the real ones, perhaps to allow the observer to concentrate on the message that those faces, those embraces, that twirling on the dance floor, emanate by virtue of the liberating process that Székely carries out every time she places herself in front of the canvas and begins to dream of that parallel world in which everything is lighter.

Even in describing landscapes, the artist does it in an idyllic manner, as if those memories, those fragments of life constituted a going back to a circumstance or a juncture in which her gaze was lost in unrepeatable instants; in the case of the panoramas, the details of the entire composition are more specific, more pertinent to what her eyes have seen, although is never lacking the sensation of immersing in a dream, in an enchanted atmosphere where everything is in its place because the heart has grasped every little detail. Indeed, in Italian idyll, Aranka Székely describes a view of an Italian seaside town where she probably spent unforgettable, carefree moments that led her to wish to imprint on canvas the beauty she had in front of her at that juncture. In the Fairy series, however, she emphasises how magical femininity can be, how much it can lead back to the world of fables where the positive, the good side, is entrusted to the hands of fairies who can protect with their aura and make us safe from everything that constitutes a threat; after all, these fantastic characters are the metaphor of the female figure, of that mixture of delicacy, sensitivity, intuition and acceptance that characterises women by nature.

In Autumn Fairy, what predominates is the light wind, the colours tending towards orange and the yellow of the leaves, despite the background being decontextualised, as if the girl had only the magic of her supernatural power around her; her face is serious but at the same time serene, as if emanating an almost unconscious positive energy, highlighted by her not looking at the observer. Similarly, Winter Fairy serenely faces the cold of the season she represents, and translated in chromatic terms with the tones of blues and whites, with a suave lightness, almost as if to counteract the frost outside by suggesting that the warmth remains constant within; it is an invitation to dance into that world paralysed by the cold without allowing the inner atmosphere to change. In this canvas too, the background is dissolved, tending towards the abstract to highlight the feelings of the girls described, that emotionality that allows them to be at ease in any environment because they are in perfect balance with themselves. It seems to be an invitation to every woman to find the same security, the same tranquillity that allows those fairies not to be influenced by the outside precisely because the balance between the positive and the negative that belongs to the human being manages to make every difficulty surmountable. In Waiting for him, therefore, the protagonist feels her feelings laid bare, she anxiously awaits the arrival of the beloved evoked by the title, of what she is not certain, and therefore seems to remain suspended in the phase of expectation, on a thread that leaves her unable to move in the fear that any action may change the course of events; the feeling of uncertainty emerges from the expression on her face, just as much as the restlessness transpires from the background, which on the one hand is tinged with the light colours of pink and yellow representing the dream of love, but on the other is contaminated by the dark blue that seems to evoke the shadowy fear that her desire will not be realised.

Aranka Székely, who has always cultivated her artistic side alongside her medical profession, has had solo and group exhibitions in Budapest, Zagreb, Rome, Florence, Zurich, Milan, Barcelona, New York, Venice, Basel, Fuerteventura, Lisbon, San Diego, Paris, Montreux, to name but the most important and she has received numerous art awards and her artworks are included in many contemporary art yearbooks.