L’arte contemporanea presenta un’innovazione assoluta rispetto ai secoli precedenti, cioè quella di aver assorbito un immenso patrimonio stilistico ed espressivo e di avere la libertà di poter reinventare, mescolandoli, stili che in passato avevano linee guida ben definite e separate da quelle di altre correnti coeve; la capacità di ciascun creativo moderno di personalizzare e interpretare le tracce lasciate dai maestri che hanno scritto la storia dell’arte, dipende dalla particolare attitudine alla sperimentazione, la stessa che aveva guidato il secolo scorso, in virtù della quale riescono a scoprire nuovi modi di fare arte. L’artista di cui vi racconterò oggi fonde insieme due tra i maggiori movimenti del recente passato, inserendovi tecniche appartenenti ad altri approcci stilistici per raccontare la realtà e la natura secondo lui.

Nel momento in cui cominciarono a delinearsi le linee guida dell’Espressionismo, in quel periodo a cavallo tra la fine dell’Ottocento e gli inizi del Novecento, ciò che più di tutto colpì l’attenzione del pubblico e dei salotti culturali dell’epoca fu la completa sovversione delle regole pittoriche così come tradizionalmente intese, con quei colori irreali e a volte persino aggressivi nella loro pienezza e con l’annullamento della prospettiva e della profondità, ma soprattutto con la prevalenza della sensazione sull’armonia delle forme. Tutto ciò che contava per i pionieri di questo stile come Henri Matisse, André Derain e Maurice de Vlaminck, i cosiddetti Fauves, era raccontare l’emozione e se per questo dovevano rinunciare alla bellezza, alla perfetta resa della realtà osservata, era un piccolo prezzo da pagare per portare all’attenzione degli amanti dell’arte un’interiorità che aveva bisogno a volte persino di gridare. Le successive evoluzioni di quelle prime intuizioni diedero vita all’Espressionismo, adattato alla personalità di ciascun autore ma sempre focalizzato sulla sfera emozionale e sul distacco dalle regole tradizionali sul disegno, sulla prospettiva, sull’utilizzo della tavolozza cromatica. Il medesimo percorso fu compiuto persino nell’Arte Informale, allorché dopo diversi decenni in cui l’Astrattismo Geometrico, il De Stijl e l’Arte Concettuale avevano promosso il completo estraniamento dell’arte nei confronti di qualunque contaminazione soggettiva e interiore, un gruppo di statunitensi capitanati da Jackson Pollock si ribellarono a questa concezione ormai superata e soprattutto limitante nel coinvolgimento del pubblico. Fu proprio Pollock a trasformare l’Arte Astratta in puro istinto introducendo il gesto creativo come parte attiva della tela attraverso il Dripping, tecnica da lui perfezionata e resa nota al pubblico, che era parte integrante di quell’Action Painting che non può essere scissa dalla sua figura artistica. Parallelamente un altro movimento rivoluzionò e scosse il mondo artistico della metà degli anni Cinquanta, la Pop Art che riprese, soprattutto nel suo ideatore Andy Warhol, la gamma cromatica irreale dell’Espressionismo con cui esaltava i simboli e le icone della società americana del tempo, tornando però a un figurativismo molto più fedele alla realtà perché il linguaggio artistico doveva arrivare diretto all’osservatore, senza intellettualismi, senza divagazioni. L’intento era quello di produrre opere in cui il grande pubblico potesse riconoscersi e trovare i simboli della quotidianità pertanto dai miti del cinema e i beni di largo consumo di Warhol, ai fumetti di Roy Lichtenstein, alle bandiere di Jasper Johns per finire alla tecnica mista fatta di ritagli di giornale e di fotografie della Pop Art inglese e italiana, come i poster strappati e incollati sulla tela tramite collage di Mimmo Rotella e gli inserti fotografici, in questo caso mescolati alla pittura, dell’inglese Richard Hamilton, tutto era funzionale a osservare la società e a riprodurne sagacemente abitudini e difetti ma soprattutto ad avvicinare l’arte alla classe borghese emergente. L’artista valdostano Andrea Zannella, confermando l’attitudine dell’arte contemporanea ad attingere al passato per dare vita a linguaggi nuovi in cui l’intento iniziale dei movimenti viene oltrepassato e adattato alle tematiche più affini all’indole del singolo artista o ad aspetti più attuali, sembra voler fondere nella sua nuova produzione le tecniche dei tre movimenti del Novecento appena menzionati.

Dunque da un lato sceglie la gamma cromatica espressionista per enfatizzare le sensazioni che riceve osservando la sua amata natura, di cui riproduce la fauna, o personaggi iconici che fanno parte del suo immaginario, e anche per scegliere un tratto pittorico impreciso perché ciò che interessa a Zannella non è riprodurre fedelmente la realtà bensì narrare le sensazioni che prova immergendosi nel mondo naturale e che trasporta sulla tela, dall’altro sporca letteralmente le opere con schizzi di colore, riprendendo la tecnica del Dripping di Pollock, per infondere ancor più incisivamente l’impeto emozionale del suo fare arte e del suo interpretare tutto ciò che colpisce la sua sensibilità artistica.

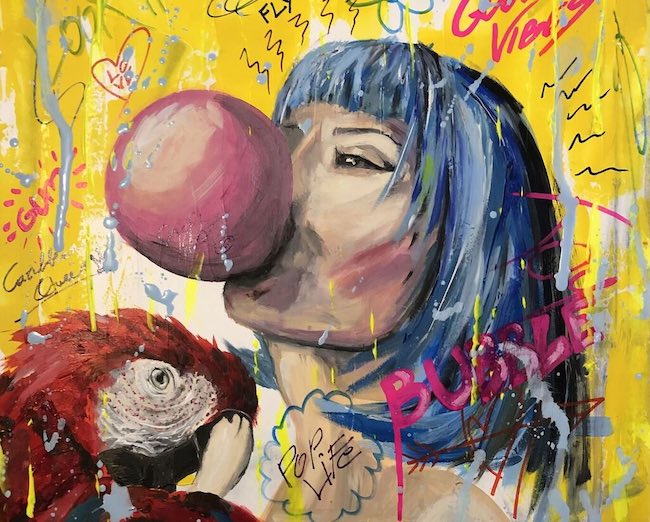

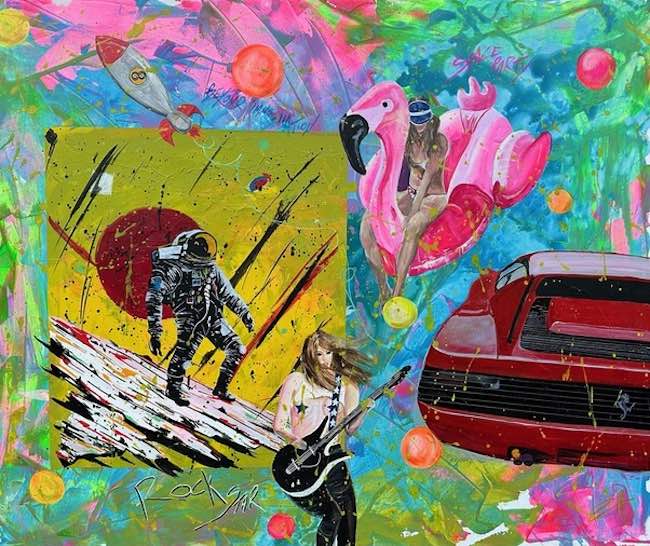

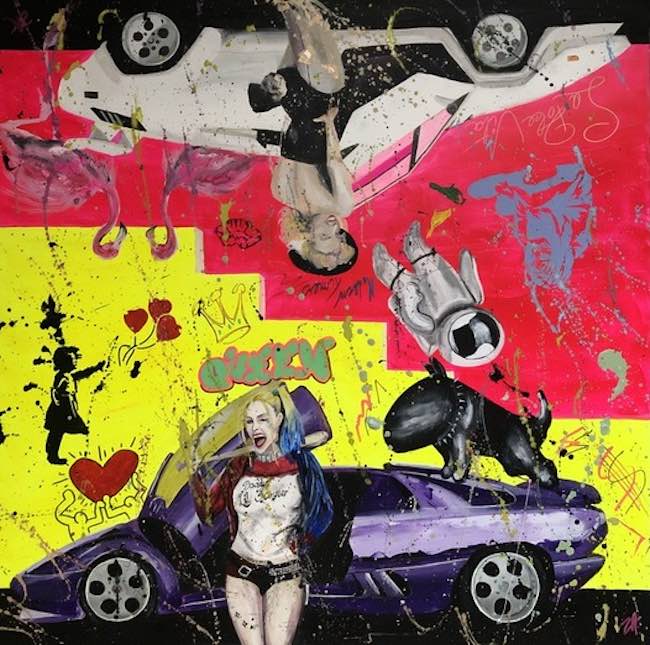

Non solo, la sua natura Pop, lo induce a evidenziare, facendoli diventare iconici, alcuni dettagli degli animali o dei personaggi che desidera raccontare, fino a giungere poi alle opere in tecnica mista dove mostra una capacità di analisi sui parallelismi tra la società di metà Novecento e quella attuale in cui le abitudini e le tendenze sono notevolmente cambiate senza che però sia cambiata la necessità dell’essere umano di uniformarsi a quelle tendenze, a quelle mode, come se in qualche modo l’omologazione fosse necessaria a sentirsi parte di un gruppo.

In quest’ultima categorie di opere Andrea Zannella introduce riferimenti al Graffitismo, evidenziato dagli sfondi vivaci arricchite da scritte che vanno a mettere in luce alcuni dettagli o concetti funzionali alla comprensione dell’opera e del pensiero dell’autore, così come la presenza di molti simboli attuali quasi in contrasto con quelli del passato, ma di fatto testimoni di come il mondo abbia solo sostituito e aggiornato le vecchie icone con altre nuove che sono le loro stesse evoluzioni, se in meglio o in peggio questo sta all’osservatore deciderlo.

La tela It’s just a point of view rappresenta in pieno questo concetto, questa contrapposizione tra ciò che era e ciò che è, tra le figure rappresentative ed emblematiche di metà Novecento, quando la Pop Art vide la luce, e quelle di oggi da cui sono state sostituite; dunque Marylin Monroe è antagonista di Harley Queen, l’antieroina della Marvel che non rappresenta certo un esempio di eleganza e buone maniere. Il bacio simbolo indiscusso degli anni Cinquanta è sostituito nella modernità dal cuore di Keith Haring, tanto quanto l’astronauta è opposto alla bambina con i palloncini rossi di Banksy e così via in una costante alternanza tra passato e presente divisi da un’ideale linea temporale ed entrambi osservabili nel dettagli capovolgendo l’opera. Ciò che resta è il mito intramontabile delle auto sportive.

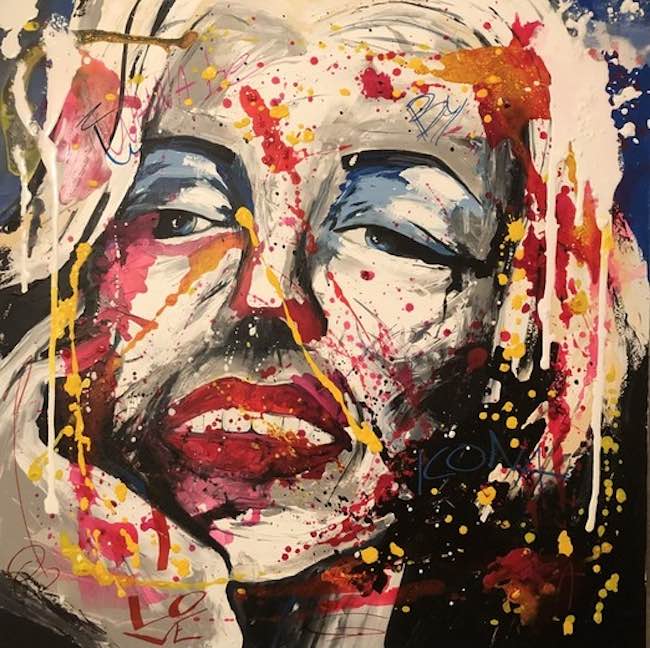

Nella tela Icona è ancora una volta Marylin Monroe a essere protagonista, sebbene privata di tutta quella perfezione estetica che forse ha contribuito a renderla poco umana, troppo inarrivabile per poter porre attenzione a un’interiorità invece molto fragile, tanto da spingerla verso un’infelicità e desiderio di amore che l’ha condotta a fare scelte sbagliate. L’interpretazione di Andrea Zannella ne mette in evidenza i colori nascosti, ne sottolinea volutamente le imperfezioni, le debolezze che traspaiono dalla posa e dal sorriso sicuri che tuttavia suonano stridenti con la malinconia nascosta dietro lo sguardo. Il Dripping diviene qui un mezzo per accentuare la rottura con l’equilibrio estetico impeccabile, come se gli schizzi di colore fossero una manifestazione di tutto ciò che la diva non è stata in grado di esprimere per tutto il corso della sua vita.

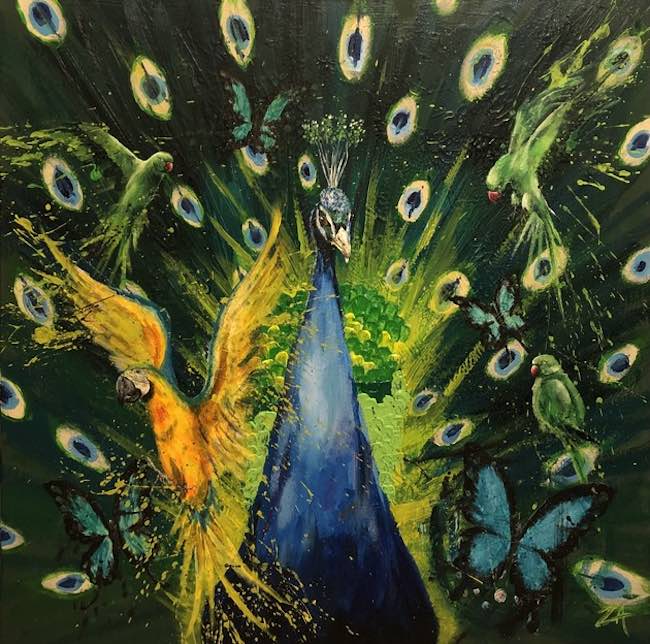

Nel dipinto Peacock Paradise Andrea Zannella mette invece in luce il mondo animale, quello dei volatili esotici come il pavone e i pappagalli circondati da farfalle che sembrano provocare un’esplosione di bellezza, di colore, di magica vitalità che fuoriesce dalla tela in virtù di un senso di movimento incrementato dall’immancabile Dripping e anche dagli occhi delle piume del pavone che sembrano non appartenere più alla coda bensì si disperdono nell’ambiente circostante come a inseguire il volo verso l’alto degli altri uccelli. Lo sfondo verde scuro è la base perfetta per far risaltare i colori degli animali, come se Zannella li avesse posti al centro di una scenografia teatrale di cui dovevano essere gli attori principali. In questa opera il tratto espressionista si ricongiunge a una perfezione descrittiva degli animali che si avvicina al Realismo, perché per l’artista sembra impossibile non raccontare i loro dettagli e la loro armonia estetica in maniera fedele alla realtà.

Andrea Zannella, pittore, scultore e fotografo, ha al suo attivo la partecipazione a molte mostre collettive in Italia e all’estero – Vienna – ricevendo consensi dal pubblico e dagli addetti ai lavori e le sue opere fanno parte di collezioni private in Italia e in Cina.

ANDREA ZANNELLA-CONTATTI

Email: andreazannella84@tiscali.it

Sito web: https://andreazannella.com/

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/andrea.zannella.7

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/zannella_andrea/

Expressionism extends its hand to Pop Art in the explosive artworks by Andrea Zannella

Contemporary art presents an absolute innovation compared to previous centuries, namely that of having absorbed an immense stylistic and expressive heritage and of having the freedom to reinvent, by mixing them, styles that in the past had well-defined guidelines separate from those of other coeval currents. The ability of each modern creative artist to personalise and interpret the traces left by the masters who wrote the history of art depends on a particular aptitude for experimentation, the same that guided the last century, by virtue of which each one is able to discover new ways of making art. The artist I am going to tell you about today fuses together two of the major movements of the recent past, incorporating techniques belonging to other stylistic approaches in order to narrate reality and nature according to his vision.

At the time when the guidelines of Expressionism began to take shape, in that period between the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century, what struck the public and the cultural salons of the time most of all was the complete subversion of the rules of painting as traditionally understood, with those unreal and sometimes even aggressive colours in their fullness and with the cancellation of perspective and depth, but above all with the prevalence of sensation over the harmony of forms. All that mattered to the pioneers of this style such as Henri Matisse, André Derain and Maurice de Vlaminck, the so-called Fauves, was to narrate emotion, and if for this they had to renounce beauty, the perfect rendering of observed reality, it was a small price to pay to bring to the attention of art lovers an interiority that sometimes even needed to be shouted out. The subsequent evolutions of those first intuitions gave birth to Expressionism, adapted to each author’s personality but always focused on the emotional sphere and on the detachment from traditional rules on drawing, perspective, and the use of the colour palette. The same path was followed even in Informal Art, when after several decades in which Geometric Abstractionism, De Stijl and Conceptual Art had promoted the complete estrangement of art from any subjective and inner contamination, a group of Americans led by Jackson Pollock rebelled against this outdated conception and above all limiting the involvement of the public. It was Pollock himself who transformed Abstract Art into pure instinct by introducing the creative gesture as an active part of the canvas through Dripping, a technique he perfected and made known to the public, which was an integral part of that Action Painting that cannot be separated from his artistic figure. At the same time, another movement revolutionised and shook the artistic world of the mid-1950s, Pop Art, which took up, especially in its creator Andy Warhol, the unreal chromatic range of Expressionism with which it exalted the symbols and icons of American society of the time, but returned to a figurativism much more faithful to reality because the artistic language had to reach the observer directly, without intellectualism, without digressions.

The intention was to produce artworks in which the general public could recognise themselves and find the symbols of everyday life, so from Warhol‘s film myths and consumer goods, to Roy Lichtenstein‘s comic strips, Jasper Johns‘ flags, and finally the mixed media of newspaper cuttings and photographs of English and Italian Pop Art, such as Mimmo Rotella‘s posters torn and glued to canvas through collage and the photographic inserts, in this case mixed with painting, by the English Richard Hamilton, everything was aimed at observing society and shrewdly reproducing its habits and faults, but above all at bringing art closer to the emerging middle class. The Valle d’Aosta artist Andrea Zannella, confirming the attitude of contemporary art to draw on the past in order to give life to new languages in which the initial intent of the movements is transcended and adapted to themes more akin to the temperament of the individual artist or to more topical aspects, seems to want to merge the techniques of the three 20th century movements just mentioned in his new production. Thus, on the one hand he chooses the expressionist chromatic range to emphasise the sensations he receives when observing his beloved nature, whose fauna he reproduces, or iconic characters that are part of his imagination, and also to choose an imprecise pictorial stroke because what interests Zannella is not to faithfully reproduce reality but to narrate the sensations he feels when immersing himself in the natural world and which he transports onto the canvas, on the other hand, he literally dirties his works with splashes of colour, echoing Pollock‘s Dripping technique, to infuse even more incisively the emotional impetus of his art-making and his interpretation of everything that strikes his artistic sensibility. Not only that, his Pop nature leads him to emphasise, making them iconic, certain details of the animals or characters he wishes to portray, to the mixed-media paintings where he shows an ability to analyse the parallels between mid-twentieth-century society and today’s one in which habits and trends have changed considerably without, however, changing the human being’s need to conform to those trends, those fashions, as if in some way homologation were necessary to feel part of a group. In this last category of works, Andrea Zannella introduces references to Graffitism, underlined by the lively backgrounds enriched by writings that highlight certain details or concepts functional to the understanding of the work and the author’s thought, as well as the presence of many current symbols almost in contrast with those of the past, but in fact witnesses of how the world has only replaced and updated the old icons with new ones that are their own evolutions, whether for the better or for the worse is up to the observer to decide. The canvas It’s just a point of view fully represents this concept, this contrast between what was and what is, between the representative and emblematic figures of the mid-twentieth century, when Pop Art saw the light, and those of today by which they have been replaced; thus Marylin Monroe is the antagonist of Harley Queen, the Marvel anti-heroine who is certainly not an example of elegance and good manners. The kiss, undisputed symbol of the 1950s, is replaced in modernity by Keith Haring‘s heart, just as the astronaut is opposed to Banksy‘s little girl with red balloons, and so on in a constant alternation between past and present divided by an ideal timeline and both observable in detail by turning the work upside down.

What remains is the timeless myth of sports cars. In the canvas Icona it is once again Marylin Monroe who is the protagonist, although deprived of all that aesthetic perfection that perhaps contributed to making her less human, too unattainable to be able to pay attention to an interiority that was instead very fragile, so much so as to push her towards an unhappiness and desire for love that led her to make wrong choices. Andrea Zannella‘s interpretation highlights her hidden colours, deliberately emphasises her imperfections, the weaknesses that transpire from her confident pose and smile, which nevertheless sound jarring with the melancholy hidden behind her gaze. Dripping here becomes a means of accentuating the break with the impeccable aesthetic balance, as if the splashes of colour were a manifestation of everything the diva was unable to express throughout her life. In the painting Peacock Paradise, Andrea Zannella instead highlights the animal world, that of exotic birds such as peacocks and parrots surrounded by butterflies that seem to provoke an explosion of beauty, of colour, of magical vitality that escapes from the canvas by virtue of a sense of movement increased by the ever-present Dripping and also by the eyes of the peacock’s feathers that seem no longer to belong to the tail but to disperse in the surrounding environment as if chasing the upward flight of the other birds. The dark green background is the perfect basis for bringing out the colours of the animals, as if Zannella had placed them at the centre of a theatrical set in which they were to be the main actors. In this painting, the expressionist trait is reunited with a descriptive perfection of the animals that approaches Realism, because it is impossible for the artist not to portray their details and aesthetic harmony in a manner faithful to reality. Andrea Zannella, painter, sculptor and photographer, has participated in many group exhibitions in Italy and abroad – Vienna – receiving acclaim from the public and insiders, and his artworks are part of private collections in Italy and China.