A volte un punto di vista, un ricordo, un paesaggio non possono essere rappresentati in maniera nitida e definita, perché all’interno di essi si affollano frammenti di emozioni, di particolari colti attraverso la sensibilità che non corrispondono all’osservato, e dunque l’artista può avvertire l’esigenza di trovare un approccio pittorico in grado di divenire voce di quelle sfaccettature indefinibili eppure tutte essenziali per interpretare ciò che la sua interiorità coglie. Il protagonista di oggi sceglie uno stile in cui il velo delle sensazioni costituisce la linea guida delle sue opere lasciando la figurazione in secondo piano, come se lo sguardo non riuscisse a mettere a fuoco ciò che è stato osservato attraverso la sensibilità, attraverso quella morbidezza dell’anima che diviene filtro di ciò che gli occhi vedono mentre la materia, i graffi, la stratificazione del colore sembrano voler scolpire quei frammenti di memoria o di paesaggi immaginari.

Nel corso dei primi ventenni del Novecento si susseguirono una serie di rivoluzioni espressive che si proponevano di superare un punto di vista classico e figurativo sulla pittura e sull’arte, dando vita a diversi movimenti in cui la rottura con il passato e il distacco da tutto ciò che l’occhio poteva riconoscere erano funzionali ad affermare la supremazia della purezza del gesto plastico, senza che venisse coinvolta la soggettività dell’esecutore dell’opera. Ben presto però la totale astrazione e il completo distacco dell’emotività richiesti nelle correnti più radicali come il Neoplasticismo, il Suprematismo e il Costruttivismo, l’Astrattismo Geometrico e la Bauhaus, mostrarono il loro limite soprattutto riguardo al coinvolgimento dell’osservatore che non riceveva dalle immagini quell’energia comunicativa che si genera invece quando un’opera viene arricchita dal sentire dell’artista che la realizza. Dunque intorno agli anni Quaranta nacque l’Espressionismo Astratto in cui fondamentale era recuperare quel mondo emotivo troppo a lungo escluso dalla nuova arte pur mantenendo però il distacco dalla realtà osservata perché era proprio in virtù della libertà esecutiva e formale che il contatto con le emozioni, l’immediatezza del lasciar fluire tutto ciò che apparteneva all’interiorità, poteva fuoriuscire in maniera intensa e priva di qualsiasi condizionamento. In Italia il movimento pittorico fu riadattato e rielaborato secondo le tendenze avanguardiste che da un lato volevano allinearsi ai colleghi statunitensi ma dall’altro intendevano anche far emergere la propria voce in maniera netta e distinguibile, dando vita pertanto a una mescolanza tra astrazione e materia che prese il nome di Arte Informale Materica, dove le sensazioni dovevano essere esaltate e rese più concrete, più incisive, con l’uso di plastiche, sabbie, iuta, metalli, lamiere come nelle impetuose opere di Alberto Burri dove il sentire sembrava voler scaturire dalla materia ed esplodere verso l’esterno legandosi e emozioni che non volevano più essere trattenute, o come in quelle dello spagnolo Antoni Tapìes evocative di una dimensione in cui la materia stessa diveniva messaggio per l’osservatore.

L’artista laziale Amadio Lancia, nato e cresciuto a Rieti dove tuttora vive, rielabora i concetti dell’Espressionismo Astratto e dell’Informale Materico mescolandoli e fondendoli per adattarli alla sua inclinazione pittorica, quella in cui la realtà interiore, il mondo emozionale non può essere assolutamente definito ma neanche totalmente distaccato dall’osservato poiché le sensazioni per riemergere e manifestarsi sulla tela cercano un contatto con il visibile, trasformato, rarefatto dalla coltre dell’interiorità che ne scorpora e ne confonde i confini infondendo alle sue opere una suggestione che non può fare a meno di conquistare lo sguardo dell’osservatore il quale ricerca i riferimenti pur avvertendo il trasporto nei confronti dell’immagine globale, della visione d’insieme in grado di far vibrare le sue corde emotive riconoscendo alle tele di Lancia un’atmosfera di familiarità, come se potessero adattarsi alla memoria di ciascuno.

Al medesimo tempo, proprio per sottolineare la rilevanza di quelle sensazioni colte durante viaggi o esperienze del passato, diventa essenziale per l’artista concretizzare o mettere in risalto alcuni frammenti, alcuni dettagli attraverso la consistenza del gesso, dello stucco o del colore acrilico dato a più strati in modo da donargli un’apparenza solida, stratificata. Oppure graffiandone la superficie per incidere i sentimenti che fuoriescono dal suo scrigno emotivo nel momento in cui si pone in dialogo con la tela per rappresentare un istante contemplato e poi sfuggito, osservato ma poi allontanato da una distanza fisica o esistenziale che lo ha portato in un altro luogo; tuttavia le immagini si sono incise nel ricordo, scontornandone i confini e i limiti fisici per entrare nell’indefinito mondo dell’immaterialità della memoria, quella terra di mezzo tra la realtà e l’impalpabilità di ciò che appartiene al ricordo.

I paesaggi sono pertanto luoghi che potrebbero essere lì, dove li colloca Amadio Lancia perché ispirati da un viaggio o da un’esperienza vissuta, oppure in qualsiasi altro posto l’interiorità dell’osservatore li riconduca, nei momenti in cui si lascia trasportare dalla suggestione che le opere riescono a suscitare. La gamma cromatica è varia e si assoggetta non solo al tipo di paesaggio o di sensazione riprodotti bensì anche allo stato emotivo in cui l’artista si trovava nella fase in cui è iniziato il suo approccio alla tela, quella scintilla creativa mossa da uno stato emotivo che poi si manifesta attraverso la pittura.

Il dipinto America racconta di una veduta dal mare, o dal largo di uno dei grandi laghi statunitensi, su cui dominano i grattacieli tipici che però appaiono sfocati, come se la meraviglia nello sguardo di Lancia si fosse soffermata sulla totalità di quella veduta, fosse stata suscitata da quell’incontro tra acqua e palazzi rappresentativo delle grandi città. Non si percepisce il rumore del traffico, le sirene delle ambulanze, i clacson, le persone che camminano velocemente bensì si respira il silenzio di un punto di vista privilegiato, quello dal largo dello specchio d’acqua su cui si affacciano i palazzi e che consente alla vista di godere dello spettacolo senza dover fare i conti con tutto ciò che quella bellezza implica.

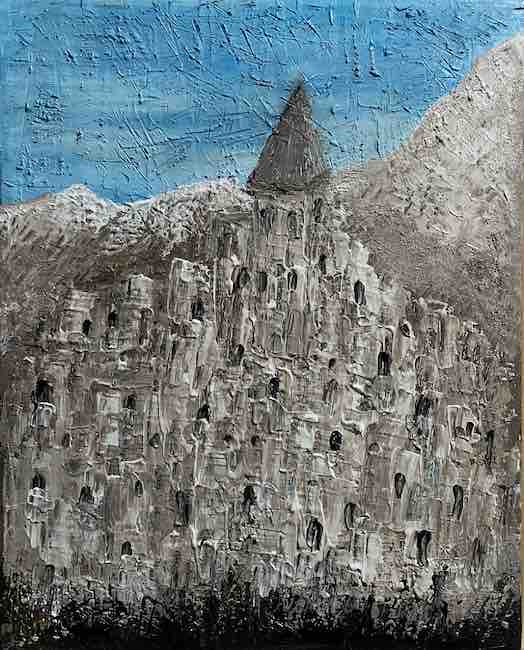

In Borgo montano invece la figurazione sembra voler emergere più incisivamente, sebbene sempre stemperata da un approccio mnemonico oppure immaginario in cui l’artista riunisce e somma differenti frammenti di scorci, poiché le case, abbarbicate le une sulle altre, segnano il profilo e l’essenza dell’opera stessa, con quell’essere tanto simili sempre perché nella memoria dell’artista ciò che conta è il colpo d’occhio completo, oltre alla sensazione che la vista di tanto fascino ha esercitato su di lui nel momento in cui si è sentito rapito allo scorcio montano. I graffi sulla parte dell’opera riservata al cielo infondono alla composizione un senso nostalgico di antichi sapori, quel senso di un passato che emerge dalle case e si propaga verso l’azzurro, pur costituendo il presente per tutte quelle persone che in quei luoghi tutt’ora abitano.

Nella tela Ho inventato un’alba Amadio Lancia fonde la sua immaginazione, che appare come la rappresentazione pittorica di molte aurore viste nel corso della sua vita, all’esigenza di sperimentare materiali attraverso i quali dare consistenza a quel paesaggio idilliaco fatto solo di acqua, montagne e cielo; dunque per realizzare l’opera utilizza colori acrilici e tempere, sabbia, glitter e colla, in virtù dei quali definisce i confini degli elementi presenti, dona consistenza alle parti che per lui sono essenziali a infondere nell’osservatore la medesima emozione percepita nel momento in cui la sua fantasia espressiva dava vita al dipinto.

E ancora in Trondheim a modo mio Lancia racconta le tipiche case norvegesi mettendo in risalto i dettagli che lo hanno colpito, i colori vivaci e intensi in contrasto con le finestre bianche, che sembrano dunque assumere consistenza grazie alla pennellata densa, e con il cielo piovoso, sottolineando quanto proprio il contrasto tra il grigio e il freddo del nord e la scelta degli abitanti di contrastarlo dipingendo di giallo, rosso e azzurro i palazzi di legno che li accolgono ogni giorno. Amadio Lancia ha al suo attivo molte mostre collettive, sia in Italia che all’estero, e una personale presso la Sala Esposizioni Phoebus di Velletri (Roma), malgrado abbia deciso solo recentemente di mostrare al pubblico le sue opere riscuotendo tuttavia ottimi consensi anche dagli addetti ai lavori.

AMADIO LANCIA-CONTATTI

Email: amadeus961@gmail.com

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100071253323486

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/armaduk61/

The Informal Art by Amadio Lancia, when abstraction and figuration meet in the world of matter

Sometimes a point of view, a memory, a landscape cannot be represented in a clear and defined manner, because within them are crowded fragments of emotions, of details captured through sensitivity that do not correspond to the observed, and therefore the artist may feel the need to find a pictorial approach capable of becoming the voice of those indefinable facets yet all essential to interpreting what his interiority grasps. Today’s protagonist chooses a style in which the veil of sensations constitutes the guiding line of his artworks, leaving figuration in the background, as if the gaze were unable to focus on what has been observed through sensitivity, through that softness of the soul that becomes the filter of what the eyes see while the material, the scratches, the layering of colour seem to want to sculpt those fragments of memory or imaginary landscapes.

During the first two decades of the 20th century took place a series of expressive revolutions that aimed to overcome a classical and figurative point of view on painting and art, giving rise to several movements in which the break with the past and the detachment from everything that the eye could recognise were functional to affirming the supremacy of the purity of the plastic gesture, without involving the subjectivity of the work’s executor. Soon, however, the total abstraction and the complete detachment of emotionality demanded in the most radical currents such as Neoplasticism, Suprematism and Constructivism, Geometric Abstractionism and Bauhaus, showed their limits, above all with regard to the involvement of the observer who did not receive from the images that communicative energy that is generated instead when a work is enriched by the feeling of the artist who creates it. Thus, around the 1940s was born Abstract Expressionism in which it was fundamental to recover that emotional world too long excluded from the new art while maintaining detachment from the observed reality because it was precisely in virtue of the freedom of execution and form that contact with the emotions, the immediacy of letting all that belonged to the interiority flow, could come out in an intense manner free of any conditioning.

In Italy, the painting movement was readapted and reworked according to the avant-garde tendencies that on the one hand wanted to align themselves with their American colleagues but on the other hand also wanted to bring out their own voice in a clear and distinguishable manner, thus giving rise to a mixture of abstraction and matter that took the name of Materic Informal Art, where sensations were to be enhanced and made more concrete, more incisive, with the use of plastics, sand, jute, metals, sheet metal as in the impetuous artworks of Alberto Burri where feeling seemed to want to spring from matter and explode outwards, binding itself and emotions that no longer wanted to be held back, or as in those of the Spanish Antoni Tapìes evocative of a dimension in which matter itself became a message for the observer. The Lazio artist Amadio Lancia, born and raised in Rieti where he still lives, reworks the concepts of Abstract Expressionism and Materic Informalism, mixing and blending to adapt them to his pictorial inclination, one in which the inner reality, the emotional world cannot be absolutely defined but neither can it be totally detached from the observed, since the sensations, in order to re-emerge and manifest themselves on the canvas, seek contact with the visible, transformed, rarefied by the blanket of interiority, which distorts and blurs its boundaries, infusing his artworks with a suggestion that cannot fail to captivate the observer’s gaze, who searches for references while feeling transported towards the global image, the overall vision capable of vibrating his emotional chords, recognising in Lancia’s canvases an atmosphere of familiarity, as if they could be adapted to the memory of each one.

At the same time, precisely in order to emphasise the relevance of those sensations captured during travels or experiences in the past, it becomes essential for the artist to concretise or highlight certain fragments, certain details through the consistency of plaster, stucco or acrylic colour given in several layers so as to donate them a solid, layered appearance. Or by scratching its surface to engrave the feelings that come out of its emotional treasure chest at the moment in which it places itself in dialogue with the canvas to represent an instant contemplated and then escaped, observed but then distanced by a physical or existential distance that has taken it to another place; however, the images have etched themselves into memory, blurring its boundaries and physical limits to enter the indefinite world of the immateriality of memory, that middle ground between reality and the impalpability of what belongs to memory. The landscapes are therefore places that could be there, where Amadio Lancia places them because they were inspired by a journey or a lived experience, or anywhere else the interiority of the observer brings them back, in the moments when he lets himself be carried away by the suggestion that the artworks manage to arouse. The range of colours is varied and is subject not only to the type of landscape or sensation reproduced but also to the emotional state the artist was in at the stage when he began his approach to the canvas, that creative spark moved by an emotional state that then manifests itself through painting. The painting America recounts a view from the sea, or from the shore of one of the great American lakes, over which the typical skyscrapers dominate, but appear blurred, as if the wonder in Lancia’s gaze had lingered on the totality of that view, had been aroused by that encounter between water and buildings representative of great cities.

One does not perceive the noise of traffic, ambulance sirens, horns, people walking quickly, but rather breathes in the silence of a privileged viewpoint, the view from the wide expanse of water overlooked by the buildings and allowing the viewer to enjoy the spectacle without having to deal with all that that beauty implies. In Borgo montano, on the other hand, figuration seems to want to emerge more incisively, although always diluted by a mnemonic or imaginary approach in which the artist brings together and sums up different fragments of views, as the houses, clinging one on top of the other, mark the profile and essence of the artwork itself, with that being so similar always because in the artist’s memory what counts is the complete glimpse, as well as the sensation that the sight of so much fascination has exerted on him at the moment he felt enraptured by the mountain view. The scratches on the part of the painting reserved for the sky infuse the composition with a nostalgic sense of ancient flavours, that sense of a past that emerges from the houses and spreads out towards the blue, while constituting the present for all those people who still live there.

In the canvas I invented a dawn Amadio Lancia fuses his imagination, which appears as the pictorial representation of many auroras seen during his life, with the need to experiment with materials through which to give substance to that idyllic landscape made up only of water, mountains and sky; thus, to realise the artwork he uses acrylic paints and tempera, sand, glitter and glue, by virtue of which he defines the boundaries of the elements present, gives consistency to the parts that for him are essential to instil in the observer the same emotion perceived at the moment when his expressive imagination gave life to the painting. And again in Trondheim in my way, Lancia describes the typical Norwegian houses by highlighting the details that struck him, the bright and intense colours contrasting with the white windows, which thus seem to take on consistency thanks to the dense brushstrokes, and with the rainy sky, emphasising how much the contrast between the grey and cold of the north and the inhabitants’ choice to contrast it by painting the wooden buildings that welcome them every day in yellow, red and blue. Amadio Lancia has many group exhibitions to his credit, both in Italy and abroad, as well as a solo exhibition at the Phoebus Exhibition Hall in Velletri (Rome), although he has only recently decided to show his works to the public, which has nevertheless met with great approval from insiders.