La tendenza a riprodurre nel dettaglio tutto ciò che appare davanti allo sguardo è essenziale per tutti quegli artisti che hanno bisogno di tenersi ben legati alla realtà per poter poi eventualmente, in una seconda fase, scendere nelle profondità, andare oltre l’estetica e dare un senso più coinvolgente proprio perché attraverso quel forte realismo sono in grado di cogliere quella luce, quella piega, quel significato che altrimenti sfuggirebbe, non sarebbe affine al loro modo di scrutare il visibile. La protagonista di oggi fa della realtà osservata la base di uno stile raffinato ed elegante ma anche attento al mistero che ogni persona, ogni circostanza, ogni oggetto portano con sé.

Gli inizi del Ventesimo secolo furono un periodo rivoluzionario e sopra le righe perché gli artisti evidenziarono la necessità di distaccarsi completamente da un approccio classico, tradizionale, così come lo era stato fino all’Ottocento, prediligendo nuove forme espressive, nuove modalità pittoriche e scultoree funzionali ad allontanarsi dalle nuove tecnologie emergenti, in particolar modo dalla fotografia considerata una mera e meccanica riproduzione della realtà, ma anche ad affermare quanto l’arte non dovesse necessariamente essere attinente all’osservato per trasmettere emozioni, sensazioni o per costituire un’elevazione dalla contingenza anche solo attraverso il gesto plastico fine a se stesso. Dunque il Realismo di fine Diciannovesimo secolo fu letteralmente rinnegato da tutti i movimenti che seguirono, partendo dall’Espressionismo e passando dal Futurismo, dall’Astrattismo per finire ai movimenti più estremi di distacco dalla tradizione e dell’immagine come il Neoplasticismo, lo Spazialismo e il Minimalismo. Il Surrealismo e la Metafisica invece, pur mantenendo intatta la riproduzione della realtà così come conosciuta dallo sguardo, se ne allontanava per l’intento espressivo di raccontare il mondo dei sogni o degli incubi decontestualizzando per questo oggetti e situazioni estraniandoli da una contingenza quotidiana non conforme al mondo sommerso che volevano far emergere. Con l’avanzare del Novecento però alcuni movimenti vollero opporsi alle avanguardie che sembravano voler trainare l’arte dell’epoca mantenendosi invece strettamente legati all’oggettività, alla realtà vissuta, e dimostrando che quell’attinenza all’immagine non era preclusiva per un’esplorazione più profonda, più intensa dei significati che si celavano oltre anzi, forse era proprio in virtù di quella vicinanza al riconoscibile che poteva emergere l’interpretazione dell’artista nei confronti dei soggetti immortalati. Il Realismo Americano, con le atmosfere rarefatte e meditative di Edward Hopper, e il Realismo Magico con le ambientazioni domestiche di Felice Casorati furono la base di partenza di un nuovo stile pittorico che inizialmente si poneva come riproduzione fedele e fotografica di tutto ciò che si trovava di fronte allo sguardo dell’artista; la nuova corrente prese il nome di Fotorealismo e aveva come obiettivo quello di avvicinare l’arte alle persone riproducendo immagini che potessero riconoscere, come d’altronde negli stessi anni stava facendo la Pop Art, ma esaltando la bellezza della modernità nella sua evidenza, quella facilmente riscontrabile dall’occhio umano. Le strade statunitensi di Richard Estes con i loro riflessi e la loro luminosità, le biglie e i flipper di Charles Bell e i tavoli delle tavole calde di Ralph Goings hanno costituito un incredibile spaccato di vita degli anni Cinquanta del Novecento, svelando, malgrado l’intenzione pittorica degli autori, abitudini, pensieri, approccio alla vita della società di quel periodo. Già con Goings si stava cominciando a compiere l’evoluzione verso un Iperrealismo Metafisico che infonde in quelle immagini perfettamente raccontate, una spinta all’approfondimento e all’indagine nei confronti di ciò che si nasconde oltre, a una riflessione più universale che non quella meramente legata all’oggetto o all’ambientazione in sé.

L’artista lucana Teresa Visceglia si avvale di un Iperrealismo meno fotografico e più morbido per lasciar emergere ogni singolo particolare di ciò che osserva pur andando subito oltre l’aspetto puramente estetico e avvolgendo le sue opere di quel mistero sottile attraverso cui suggerisce all’osservatore che vi è altro sotto la patina superficiale; la sua delicatezza espressiva si fonde alla sensibilità empatica con cui non solo scruta fin nei dettagli ciò che desidera diventi protagonista delle sue tele ma interpreta anche quel sottile oltre che senza la sua attenta capacità di portarlo alla luce non trasparirebbe.

Lo sguardo della Visceglia si muove su più fronti, sempre vigile nell’estrapolare un senso diverso, nascosto e per questo affascinante, perché la realtà, le energie segrete esistono sia in soggetti vivi che in quelli apparentemente inanimati; dunque ritratti attuali o reinterpretazioni di icone del passato divengono protagonisti delle sue tele tanto quanto le nature morte, ritrovando quel piacere nelle piccole cose che era appartenuto a Giorgio Morandi e che in lei si avvale di una tecnica pittorica di grande precisione, di incredibile maestria nel disegno come nell’ombreggiatura del colore necessari a donare alle opere l’alta definizione di cui tanto si avvale la tecnologia contemporanea.

Ecco, in Teresa Visceglia quel risultato è raggiunto attraverso l’arte, un approccio completamente manuale che, pur richiedendo un processo ben più lungo rispetto alla macchina fotografica, ne assume le sembianze ma subito dopo ne oltrepassa i confini lasciando sulla tela l’intenzione dell’artista, il suo pensiero, il suo sguardo indagatore sull’essenza di tutto ciò che i suoi occhi vedono.

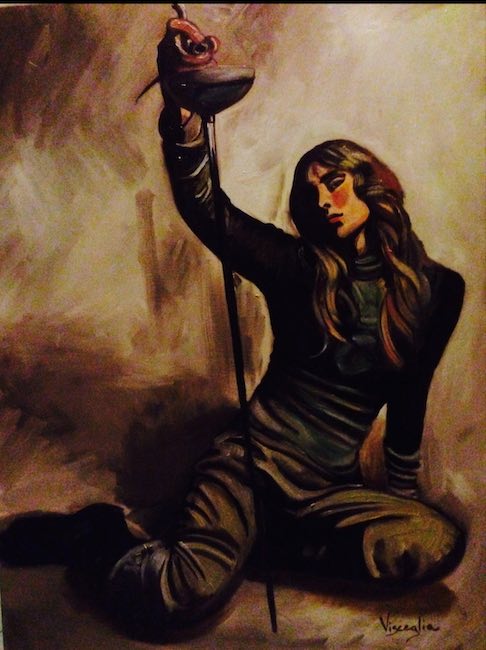

Nel dipinto Africa l’artista immortala una donna, forse una regina, una ricca ereditiera o semplicemente un’appartenente al popolo che mostra da un lato un atteggiamento solenne che incute rispetto, dall’altro la riflessione nei confronti di una società forse ancora troppo a predominio maschile che la induce a domandarsi se è davvero giusto accettare che sia così. Lo sguardo della Visceglia va oltre la bellezza perfettamente curata e il sontuoso copricapo, scende verso gli occhi abbassati non per riverenza bensì per meditazione a cercare il modo di emergere malgrado tutto; ne sottolinea l’avvenenza e al contempo ne lascia intuire la capacità inconfessata di dare valore anche a tanto altro che esula dalla forma esteriore, a un desiderio di essere considerata per le sue reali capacità e non solo per il fatto di essere donna, giovane e bella.

Nell’opera Cartoccio l’artista sottolinea il suo amore per la semplicità di oggetti che contraddistinguono la quotidianità, quell’essere presenti nelle abitazioni e troppo spesso ignorati, lasciati distrattamente su un tavolo o su una credenza a fare da sfondo allo scorrere rapido dell’esistenza; Teresa Visceglia invece ne evidenzia il loro essere presenti, fungendo da certezze rassicuranti necessarie all’essere umano per costituire dei punti fermi, qualcosa di cui lo sguardo ha bisogno nel momento in cui decide di fermarsi e guardarsi intorno. L’artista coglie l’estetica della composizione ma anche l’aspetto meditativo, invitando quasi l’osservatore a rallentare il ritmo, a prendere fiato e apprezzare i vantaggi della lentezza, la bellezza della contemplazione.

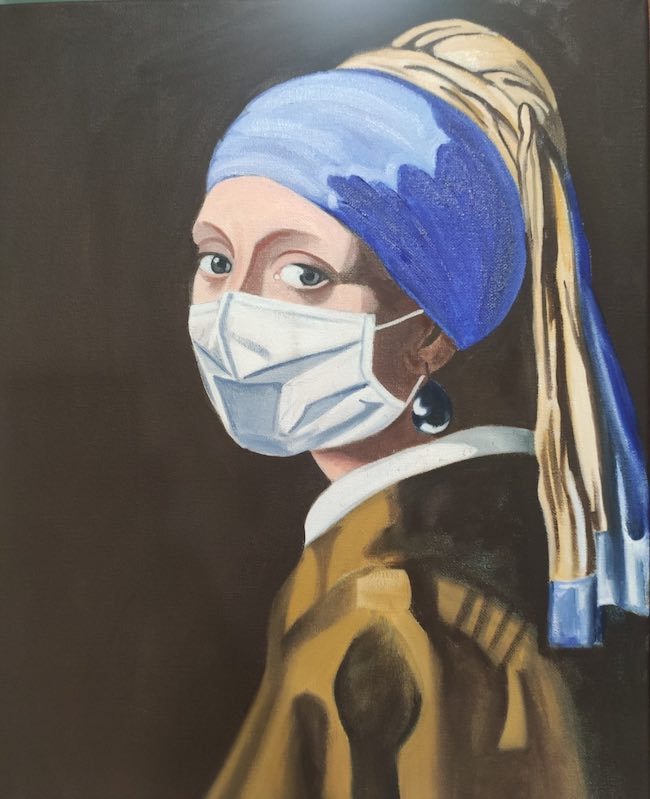

Anche in Evoluzione, Ragazza con l’orecchino di perla affronta una tematica attuale, quella del virus che negli ultimi due anni ha cambiato il mondo intero, lasciandone emergere in maniera discreta, attraverso una mascherina, tutte le implicazioni che ne derivano e che ne deriveranno ancora, domandandosi come sarebbe stata la realtà che conosciamo, compresi anche i tesori artistici del passato, se tutto fosse successo secoli fa, modificando inevitabilmente ciò che sarebbe giunto a noi dalla storia. Lo sguardo della ragazza protagonista della celeberrima opera di Jan Vermeer, sfuggente e languido nella tela originale, appare disorientato, quasi spaventato nella reinterpretazione della Visceglia, come se fosse avvolta da una profonda tristezza, forse generata dalla condizione contingente o forse dal timore che niente potrà mai essere come prima.

E ancora in Donna in rosso, di cui l’artista evidenzia l’atmosfera fumosa generata dalla sigaretta, accorda la gamma cromatica non solo all’abito della sua protagonista bensì anche alla passionalità che da lei fuoriesce, una connessione tra soggetto e ambiente circostante che viene però sottolineato e interpretato dalla sua percezione. Teresa Visceglia opera nell’arte da vent’anni, ha all’attivo numerose collettive su tutto il territorio nazionale e le sue tele sono inserite nei maggiori cataloghi dedicati all’arte contemporanea.

TERESA VISCEGLIA-CONTATTI

Email: teresavisceglia05@gmail.com

Sito web: https://www.premioceleste.it/teresa.visceglia

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/teresa_visceglia/

Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/in/teresa-visceglia-4a6b7b6b/

Teresa Visceglia’s Metaphysical Hyperrealism, interpreting reality to discover the secret behind things

The tendency to reproduce in detail everything that appears before one’s eyes is essential for all those artists who need to hold on tightly to reality in order to be able to eventually, in a second phase, descend into the depths, go beyond aesthetics and give a more involving sense precisely because through that strong realism they are able to grasp that light, that fold, that meaning that would otherwise escape, would not be akin to their way of scrutinising the visible. Today’s protagonist makes observed reality the basis of a style that is refined and elegant but also attentive to the mystery that every person, every circumstance, every object brings.

The beginning of the 20th century was a revolutionary and over-the-top period because artists highlighted the need to completely break away from a classical, traditional approach, as it had been until the 19th century, favouring new forms of expression, new pictorial and sculptural modes that were functional to move away from the new emerging technologies, in particular from photography considered a mere mechanical reproduction of reality, but also to affirm how art did not necessarily have to be related to the observed in order to convey emotions, sensations or to constitute an elevation from contingency even if only through the plastic gesture as an end in itself. Thus, late 19th century Realism was literally repudiated by all the movements that followed, starting with Expressionism and moving on to Futurism, Abstractionism and the more extreme movements of detachment from tradition and the image such as Neo-Plasticism, Spatialism and Minimalism. Surrealism and Metaphysics, on the other hand, while maintaining intact the reproduction of reality as known to the eye, distanced themselves from it with the expressive intent of recounting the world of dreams or nightmares, decontextualising for this reason objects and situations by alienating them from an everyday contingency that did not conform to the submerged world they wanted to bring out. As the 20th century progressed, however, some movements wanted to oppose the avant-garde movements that seemed to want to drive the art of the time, while remaining closely linked to objectivity, to lived reality, and demonstrating that this adherence to the image was not preclusive to a deeper, more intense exploration of the meanings that were hidden beyond it. American Realism, with the rarefied and meditative atmospheres of Edward Hopper, and Magic Realism with the domestic settings of Felice Casorati were the starting point of a new style of painting that initially set out to faithfully and photographically reproduce everything that was in front of the artist’s gaze; the new current took the name of Photorealism and had the objective of bringing art closer to people by reproducing images that they could recognise, as Pop Art was doing in the same years, but exalting the beauty of modernity in its evidence, that which is easily seen by the human eye. The American streets of Richard Estes with their reflections and luminosity, the marbles and pinball machines of Charles Bell and the tables of Ralph Goings’ diners constituted an incredible cross-section of life in the 1950s, revealing, despite the pictorial intention of the authors, habits, thoughts, approach to life in the society of that period. Already with Goings, an evolution towards a Metaphysical Hyperrealism was beginning to take place, which infuses those perfectly narrated images with a drive for in-depth analysis and investigation into what lies beyond, for a more universal reflection than that merely linked to the object or the setting in itself.

Lucanian artist Teresa Visceglia uses a less photographic and softer Hyperrealism to allow every single detail of what she observes to emerge, while immediately going beyond the purely aesthetic aspect and wrapping her artworks in that subtle mystery through which she suggests to the observer that there is more beneath the superficial patina; her expressive delicacy blends with the empathetic sensitivity with which she not only scrutinises down to the details what she wishes to become the protagonist of her canvases but also interprets that subtle beyond that without her careful ability to bring it to light would not transpire. Visceglia’s gaze moves on several fronts, always vigilant in extrapolating a different sense, hidden and for this reason fascinating, because reality, secret energies exist in both living and apparently inanimate subjects; therefore, current portraits or reinterpretations of icons of the past become protagonists of her canvases as much as still lifes, rediscovering that pleasure in small things that belonged to Giorgio Morandi and that in her makes use of a pictorial technique of great precision, of incredible mastery in drawing as in the shading of colour necessary to give the artworks the high definition that contemporary technology so much makes use of. Here, in Teresa Visceglia, that result is achieved through art, a completely manual approach that, while requiring a much longer process than the camera, takes on its semblance but immediately goes beyond its boundaries, leaving on the canvas the artist’s intention, her thought, her inquiring gaze on the essence of everything her eyes see. In the painting Africa, the artist immortalises a woman, perhaps a queen, a rich heiress or simply a member of the populace, who shows on the one hand a solemn attitude that commands respect, and on the other a reflection on a society that is perhaps still too male-dominated, leading her to wonder whether it is really right to accept that it is so. Visceglia’s gaze goes beyond the perfectly manicured beauty and the sumptuous headdress, descending towards the lowered eyes, not out of reverence but out of meditation, searching for a way to emerge in spite of everything; she emphasises her beauty and at the same time hints at her unconfessed ability to value something else that goes beyond her exterior form, a desire to be considered for her real abilities and not only for the fact that she is a woman, young and beautiful.

In the artwork Cartoccio, the artist emphasises her love for the simplicity of objects that characterise everyday life, that being present in the home and all too often ignored, left absent-mindedly on a table or sideboard as a backdrop to the rapid passing of existence; Teresa Visceglia, on the other hand, emphasises their being present, acting as reassuring certainties necessary for human beings to constitute fixed points, something that the eye needs when it decides to stop and look around. The artist captures the aesthetics of the composition but also the meditative aspect, almost inviting the observer to slow down the pace, to take a breath and appreciate the benefits of slowness, the beauty of contemplation. Also in Evoluzione, Ragazza con l’orecchino di perla (Evolution, Girl with a Pearl Earring) tackles a topical issue, that of the virus that has changed the entire world in the last two years, discreetly allowing to emerge, through a mask, all the implications that have and will still derive from it, wondering how the reality we know, including even the artistic treasures of the past, would have been if everything had happened centuries ago, inevitably modifying what would have come to us from history. The gaze of the girl protagonist of Jan Vermeer’s celebrated painting, fleeting and languid in the original canvas, appears disoriented, almost frightened in Visceglia’s reinterpretation, as if enveloped by a profound sadness, perhaps generated by the contingent condition or perhaps by the fear that nothing could ever be as it was before. And again in Donna in rosso (Woman in Red), in which the artist emphasises the smoky atmosphere generated by the cigarette, she accords the chromatic range not only to the dress of her protagonist but also to the passion that emanates from her, a connection between subject and surrounding environment that is emphasised and interpreted by her perception. Teresa Visceglia has been working in art for twenty years, has numerous group exhibitions throughout Italy to her credit and her canvases are included in major contemporary art catalogues.