Molto spesso la necessità di alcuni artisti di sussurrare in maniera lieve e sfumata le proprie emozioni, il punto di vista sulla vita manifestando, attraverso il filtro interiore, la realtà circostante, i paesaggi e le persone, si trasforma in esigenza di trovare un mezzo espressivo differente da quello tradizionale, più affine alla morbidezza di sensazioni, più preciso nel seguire il flusso emozionale e al tempo stesso più soffice proprio per rappresentare in maniera completa lo sguardo sulla realtà circostante. La protagonista di oggi utilizza una tecnica particolare per lasciar trapelare la sensibilità e il tocco morbido che la contraddistingue.

Nel corso della storia dell’arte, precisamente intorno al Sedicesimo secolo, venne ideato dall’artista francese Jean Perréal il pastello morbido che mostrò fin da subito una notevole semplicità di stesura senza tempi di asciugatura così come la capacità di lasciarsi sfumare infondendo così ai soggetti rappresentati una forte aderenza alla realtà; Leonardo da Vinci prima e la pittrice veneziana Rosalba Carriera poi ne sdoganarono l’utilizzo facendolo entrare di diritto tra le tecniche artistiche che in quell’epoca e nelle due successive, furono utilizzate dai maggiori maestri. Giovanni Boldini, Claude Monet, Edgar Degas e più in generale tutti gli artisti aderenti all’Impressionismo ne fecero largo uso poiché decisamente affine alla velocità esecutiva delle loro opere in cui il tratto del pastello si armonizzava perfettamente a quei lievi tocchi di pennello attraverso cui costruivano e davano vita alla rappresentazione della realtà con tutta la sua luce, le sue sfaccettature e la sua bellezza. In questo periodo la nuova tecnica si discostò dall’esecuzione dei ritratti, per la quale era stata maggiormente usata nel Diciottesimo secolo, ed entrò nel mondo del paesaggio, dei panorami e delle scene di rilassamento e di divertimento della borghesia, soggetti prediletti dagli impressionisti; dunque ecco nascere, in un’epoca precedente a quella delle grandi sperimentazioni e rivoluzioni che contraddistinse il Novecento, la tecnica mista su tela, quell’armonizzazione di materiali diversi, sebbene ancora prevalentemente bidimensionali, in virtù dei quali dar vita a opere più vicine alla realtà, o semplicemente più rappresentative dello stato d’animo dell’esecutore della tela per cui non era più sufficiente soffermarsi su un solo mezzo espressivo. Il pittore modernista Ramon Casas, l’impressionista spagnolo Joaquin Sorolla, lo stesso Pablo Picasso, solo per citarne alcuni, utilizzarono ampiamente il pastello anche nel Ventesimo secolo per infondere luce, sfumature e attinenza a tutto ciò che veniva osservato dallo sguardo, oppure per scolpire le figure ispirate alle maschere tribali africane da cui partì la produzione del maestro del Cubismo. L’artista friulana Milena Miculan predilige proprio questo mezzo esecutivo, il pastello secco, per narrare i suoi paesaggi che assomigliano più a luoghi dell’anima che non a posti reali, o comunque a frammenti visivi filtrati dalla sua sensibilità, dal suo approccio poetico nel percepire ciò che ruota intorno a sé e che lo sguardo coglie; unisce la meraviglia dei panorami incastonati nella sua memoria, molto vicini allo stile del Romanticismo per quel suo cogliere la grandezza della natura, dell’acqua e del cielo che contribuiscono ad accogliere l’uomo facendogli al tempo stesso percepire la sua caducità, il carattere temporaneo e fugace della sua esistenza che viene sottolineata dalla presenza perpetua e dal costante ripetersi e avvicendarsi delle stagioni e dei fenomeni atmosferici.

Ma lo sguardo della Miculan non indugia solo sull’immensità della natura bensì va oltre e ne fa fuoriuscire il lato più dolce, quello che non può fare a meno di legarsi ai ricordi e di entrare a far parte dello scrigno emotivo dell’individuo il quale, che ne sia consapevole o meno, si rivela indissolubilmente legato alle immagini intorno a sé, a quei frammenti di memoria in grado di emozionarlo perché avvolti nel suo mondo intimo.

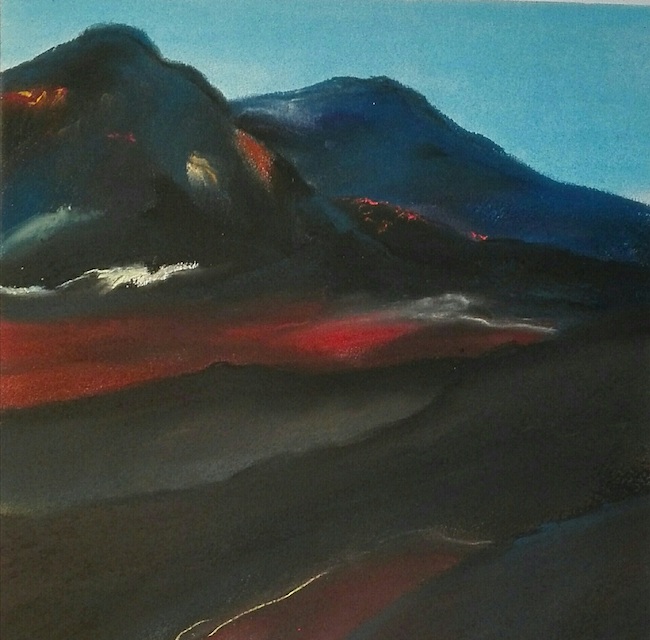

La serie di lavori intitolata Visioni d’intorno è legata alle percezioni che l’ambiente circostante infonde sull’interiorità dell’artista, suscitandole riflessioni, pulsioni intense che trapelano da quei paesaggi intensi ma soffusi, terrestri eppure lunari, rasserenanti ma anche densi di turbamento proprio perché la sfera emozionale non può essere governata dalla ragione; nella tela Dämmerung (Crepuscolo) l’impressione è di trovarsi davanti a un epilogo, metaforicamente rappresentato dalla fine di un giorno ma che può anche raccontare il punto di vista di Milena Miculan sul corso della vita, su quel dover necessariamente accettare tutto ciò che è inevitabile e proprio da quella svolta ricominciare un nuovo cammino. Il timore di affrontare il buio spesso deriva dal bisogno di restare ancorati alle certezze, malgrado spesso non ci soddisfino, così l’individuo tende a preferire restare sul proprio percorso rischiando di non scoprire mai ciò che potrebbe esservi oltre la collina, seguendo quella luce che permane perché segna un nuovo inizio; la capacità di intravedere la luce piuttosto che concentrarsi sul buio è la chiave di svolta dell’esistenza, la differenza tra il vivere coraggiosamente rischiando di vincere e il farsi sopraffare dalle paure mantenendo un’unica certezza, quella di non combattere.

Nell’opera Volo infatti l’artista sembra esortare l’osservatore a spogliarsi dalle zavorre che lo trattengono e lanciarsi verso quelle opportunità, quelle possibilità che solo compiendo un balzo coraggioso possono aprirsi; il volo è quello della fantasia, della libertà, del sogno troppo spesso lasciato in disparte a causa di un pragmatismo, di un realismo che solo apparentemente rassicurano perché in realtà contribuiscono ad allontanare la parte più reale del sé, quella più ingenua certo ma anche l’unica in grado di credere che tutto sia possibile. In questo lavoro l’atmosfera è particolarmente sfumata, rarefatta, quasi ad accompagnare, a scortare, le ali aperte dell’uccello che, pur occupando solo una piccola parte della tela ne è assoluto protagonista, simbolo del coraggio di sollevarsi e cercare altrove ciò che non è riuscito a ottenere in precedenza.

In Verso San Marco la Miculan sembra sottolineare un’emozione fortemente intima, un ricordo nostalgico nei confronti di un luogo, una piccola chiesa con cimitero annesso vicina ad Aquileia, che non è raffigurata bensì semplicemente evocata, proprio come nel percorso della memoria in virtù del quale l’artista si perde dentro l’emozione che la località da cui si vede la laguna di Grado le ha suscitato quando l’ha scoperta, respirata; l’opera rappresenta la malinconia nei confronti di una sensazione a cui il ricordo è legato, probabilmente perché vissuta in un periodo particolare dell’esistenza, in un frangente trascorso eppure ancora fortemente presente e indelebile rappresentato da quel cielo scuro, denso di nubi, come se la memoria necessitasse di soffermarsi sulla medesima atmosfera precedente. L’altra parte della produzione di Milena Miculan si intitola Umana fragilità, una serie di opere dedicate alla donna, alla sua sensibilità che solo apparentemente la rende debole ma che sa tirare fuori tutta la sua forza e determinazione nel momento in cui si rendono necessarie.

Nella tela che dà il nome alla serie la donna viene rappresentata come dentro a un guscio, quello delle sue paure e dei suoi limiti, quella gabbia dentro la quale la società la vorrebbe alla quale però lei non si rassegna, prende coscienza della necessità di trovare un suo percorso e la forza di cercare un modo differente di farsi accogliere, non più rinunciando a se stessa.

In Abitudine l’artista pone la figura femminile all’interno di un appartamento, dentro un luogo rassicurante tanto quanto intrappolanti sono quelle certezze che se da un lato costituiscono una zona sicura dall’altro impediscono di sperimentare, rischiare, buttarsi senza ali verso quel nuovo che potrebbe cambiare tutto.

Non descrive mai i volti Milena Miculan proprio per evidenziare quanto i suoi personaggi potrebbero essere chiunque, quanto le sue donne siano qualsiasi donna perché il sentire è comune, è condiviso, e perché ciò che conta non è il dettaglio fisico bensì il movimento del corpo che esprime già tutto, proprio come su un palcoscenico teatrale dove, pur non distinguendosi i volti si riesce a percepire la loro emozione solo osservandone il movimento. Milena Miculan ha al suo attivo molte mostre collettive in Italia e all’estero – Londra, Vienna, Lubiana – e a fiere e concorsi d’arte dove ha ricevuto menzioni speciali e premi.

MILENA MICULAN-CONTATTI

Email: miculan28@gmail.com

Sito web: www.leni-art.eu

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/leni.nahla

Milena Miculan, the landscape as a manifestation of the delicacy of the soul and a filter of deep feeling

Very often the need of some artists to whisper in a light and nuanced way their emotions, their point of view on life by showing, through the inner filter, the surrounding reality, landscapes and people, turns into the need to find a different expressive means from the traditional one, more akin to the softness of sensations, more precise in following the emotional flow and at the same time softer just to represent in a complete way the look on the surrounding reality. Today’s protagonist uses a special technique to reveal the sensitivity and soft touch that distinguishes her.

In the course of the history of art, around the 16th century to be precise, the French artist Jean Perréal invented the soft pastel, which immediately showed remarkable simplicity of drafting without drying time as well as the ability to let itself be blurred, thus giving the subjects represented a strong adherence to reality; first Leonardo da Vinci and then the Venetian painter Rosalba Carriera cleared customs for its use, making it a rightful entry among the artistic techniques that in that era and in the two following ones were used by the greatest masters. Giovanni Boldini, Claude Monet, Edgar Degas and, more generally, all the artists who adhered to Impressionism made extensive use of it, as it was decidedly akin to the speed of execution of their artworks in which the stroke of the pastel harmonised perfectly with those light touches of the brush through which they constructed and gave life to the representation of reality with all its light, its facets and its beauty.

At this time, the new technique moved away from portraits, for which it had been used most in the 18th century, and entered the world of landscapes, panoramas and scenes of relaxation and entertainment of the bourgeoisie, subjects favoured by the Impressionists; thus, in an era before the great experiments and revolutions of the 20th century, was born the mixed technique on canvas, that harmonisation of different materials, although still predominantly two-dimensional, with which to create works closer to reality, or simply more representative of the painter’s state of mind, for whom it was no longer sufficient to focus on a single expressive medium. The modernist painter Ramon Casas, the Spanish Impressionist Joaquin Sorolla, Pablo Picasso himself, to name but a few, used pastel extensively in the 20th century to infuse light, nuances and relevance into everything that was observed by the eye, or to sculpt the figures inspired by the African tribal masks from which the production of the master of Cubism began. Friulian artist Milena Miculan prefers this very medium, dry pastel, to narrate her landscapes, which are more like places of the soul than real sites, or at least visual fragments filtered through her sensitivity, her poetic approach to perceiving what revolves around her and what the eye catches; she combines the wonder of the panoramas set in her memory, very close to the style of Romanticism in that she captures the greatness of nature, water and sky which help to welcome man while at the same time making him perceive his transience, the temporary and fleeting nature of his existence which is underlined by the perpetual presence and constant repetition and alternation of the seasons and atmospheric phenomena.

But Miculan’s gaze does not linger only on the immensity of nature, but goes beyond it and brings out its sweeter side, the one that cannot help but bind itself to memories and become part of the emotional treasure chest of the individual who, whether he is aware of it or not, reveals himself to be inextricably linked to the images around him, to those fragments of memory capable of moving him because they are wrapped up in his intimate world. The series of artworks entitled Visioni d’intorno (Visions from around) is linked to the perceptions that the surrounding environment infuses into the artist’s interiority, arousing reflections, intense impulses that seep out of those intense yet suffused landscapes, terrestrial yet lunar, soothing but also dense with disturbance precisely because the emotional sphere cannot be governed by reason; in the painting Dämmerung (Twilight), the impression is of being faced with an epilogue, metaphorically represented by the end of a day, but which can also recount Milena Miculan’s point of view on the course of life, on having to necessarily accept all that is inevitable and to start a new path precisely from that turning point. The fear of facing the dark often derives from the need to remain anchored to certainties, despite the fact that they often do not satisfy us, so the individual tends to prefer to stay on his own path, risking never discovering what might be beyond the hill, following that light which remains because it marks a new beginning; the ability to glimpse the light rather than concentrating on the dark is the key to the turning point of existence, the difference between living courageously, risking winning, and letting oneself be overwhelmed by fears, maintaining a single certainty, that of not fighting.

In the artwork Volo (Flight) the artist seems to be exhorting the observer to strip himself of the ballast that holds him back and to launch himself towards those opportunities, those possibilities that can only open up by taking a courageous leap; flight is that of fantasy, of freedom, of the dream that is all too often left aside because of a pragmatism and a realism that only apparently reassure because in reality they contribute to distancing the most real part of himself, the most naive side, but certainly also the only one capable of believing that everything is possible. In this artwork, the atmosphere is particularly nuanced, rarefied, almost as if to accompany, to escort, the open wings of the bird which, although it occupies only a small part of the canvas, is the absolute protagonist, the symbol of the courage to rise up and look elsewhere for what it has not previously been able to achieve. In Verso San Marco (Towards San Marco) Miculan seems to underline a strongly intimate emotion, a nostalgic memory of a place, a small church with an adjoining cemetery near Aquileia, which is not depicted but simply evoked, just as in the path of memory by virtue of which the artist loses herself in the emotion that the place from which she can see the lagoon of Grado aroused in her when she discovered it, breathed it in; the work represents the melancholy towards a sensation to which the memory is linked, probably because it was experienced in a particular period of existence, in a past juncture and yet still strongly present and indelible represented by that dark sky, dense with clouds, as if the reminiscence needed to dwell on the same previous atmosphere.

The other part of Milena Miculan’s production is entitled Umana fragilità (Human fragility), a series of artworks dedicated to women, to their sensitivity which only apparently makes them weak but which they know how to bring out all their strength and determination when they are needed. In the canvas that gives the name to the series, the woman is represented as being inside a shell, that of her fears and limits, the cage in which society would like her to be, but she does not resign herself to it, becoming aware of the need to find her own path and the strength to seek a different way of being accepted, no longer renouncing herself. In Abitudine (Habit), the artist places the female figure inside a flat, inside a place that is as reassuring as those certainties are trapping her, which on the one hand constitute a safe zone but on the other prevent her from experimenting, risking, throwing herself without wings towards the new that could change everything. Milena Miculan never describes faces in order to emphasise how her characters could be anyone, how her women are any woman, because the feeling is common, it is shared, and because what counts is not the physical detail but the movement of the body, which already expresses everything, just as on a theatre stage where, although the faces cannot be distinguished, it is possible to perceive their emotion just by observing their movement. Milena Miculan has to her credit many group exhibitions in Italy and abroad – London, Vienna, Ljubljana – and at art fairs and competitions where she has received special mentions and awards.