L’universo creativo di ciascun artista si adegua, o sarebbe meglio dire si asseconda, alla personalità espressiva spesso persino discostante da ciò che traspare nella quotidianità; questo perché la creatività sceglie una strada a sé stante, va oltre tutta quella patina di autocontrollo che è necessario mettere in campo nell’affrontare la vita. Ecco dunque che l’arte diviene mezzo per esprimere la propria reale essenza, quella reale sostanza interiore nascosta ma, in virtù del gesto plastico, in grado di trovare il proprio canale comunicativo che racconta molto di più di quanto le parole non riescano a raccontare. Il protagonista di oggi trova nella vivacità cromatica il suo linguaggio prediletto affidando ai colori il compito di spiegare, interpretare e mettere in evidenza dettagli, sensazioni ed emozioni dei personaggi e dei luoghi che di volta in volta sceglie di porre al centro della scena.

La prima, inaspettata ribellione nei confronti dell’arte tradizionale, quella di cui fino a poco prima si erano attentamente rispettate le regole accademiche e le linee guida irrinunciabili per rappresentare l’armonia e la bellezza dell’essere umano tanto quanto della natura, fu generata da un gruppo di artisti francesi che si riunivano nei salotti artistici per elaborare nuove teorie, nuove possibilità che andavano addirittura a stravolgere tutti gli schemi precedenti. In quei primissimi anni del Novecento i Fauves decretarono la fine della tradizione pittorica come classicamente intesa sottolineando l’importanza del sentire dell’esecutore dell’opera, della sua interiorità e anche del mondo raccontato di cui la cromaticità non doveva più essere attinente all’osservato bensì necessariamente assecondarsi a quelle emozioni che inevitabilmente accompagnano l’essere umano in ogni singolo istante. Al fine di ottenere il risultato interpretativo che cercavano, sapevano di dover rinunciare a a quell’armonia, a quella perfezione che aveva contraddistinto il Realismo e l’Impressionismo, alla ricerca della prospettiva, delle sfumature coloristiche, a tutto ciò che in qualche modo avrebbe distratto lo sguardo dall’intensità del narrato. Dunque gli appartenenti al movimento, che ben presto evolse trasformandosi in Espressionismo, di cui Henri Matisse, Maurice de Vlaminck e André Derain furono i maggiori esponenti, decisero di optare per una tavolozza di colori intensa e spesso irreale, di non dettagliare i volti e i particolari trasformando i personaggi in proiezioni delle loro stesse sensazioni, e di contornarli con un evidente tratto grafico come a voler contenere e al tempo stesso distinguere ciò che apparteneva all’individuo e il mondo circostante che si adeguava all’emanazione del soggetto. Con l’evoluzione verso l’Espressionismo le tonalità intense e a volte persino aggressive dei Fauves si attenuarono, perché ormai il punto di rottura era stato raggiunto e il cambiamento si era verificato, tuttavia ciò che non venne mai perduto o rinnegato fu l’approccio non estetico alla tela, l’inutilità di rappresentare la realtà in modo fedele o di concentrarsi sull’armonia figurativa; fu conservato il tratto grafico, più o meno evidente a seconda dell’intento espressivo di ciascun aderente al movimento, così come la tendenza a sfidare le regole e il buongusto dell’epoca mettendo a nudo vizi e virtù, debolezze e depravazioni, angosce e inquietudini. Laddove Egon Schiele ed Edvard Munch scelsero tonalità meno aggressive, cupe o neutre ma comunque meno vivaci, Emil Nolde ed Ernst Ludwig Kirchner mantennero invece una tavolozza cromatica forte e impattante per sottolineare il messaggio che le loro tele contenevano. L’artista di origine lombarda, ma residente a Pescara da innumerevoli anni, Claudio De Gregorio, in arte COG, sceglie l’approccio interpretativo dell’Espressionismo, quello che mantiene ancora in modo predominante l’eredità cromatica dei Fauves, per dare il suo punto di vista emozionale su ciò che cattura il suo sguardo, generando tonalità coloristiche originali e spesso con predominanza del giallo; perché al giallo è legata l’immagine del sole, della luce, della primavera, dell’allegria ma anche dell’eleganza e della raffinatezza in alcuni casi.

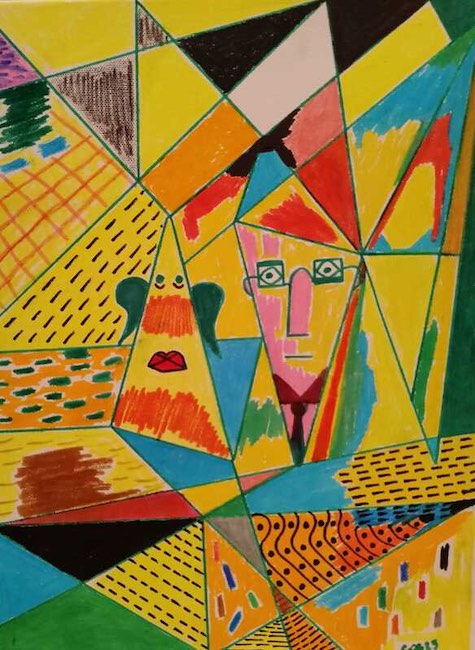

La declinazione di questa tonalità cromatica è dunque il comune denominatore delle tele di De Gregorio che talvolta passa attraverso la scomposizione del Neo Cubismo a cui mescola la vitalità tonale del Cubismo Orfico, perché in alcuni casi è necessario scomporre le sensazioni percepite e ricomporle secondo l’ordine interiore, e solo dopo questa operazione si può comprenderne i risvolti; ciò che accomuna le opere dell’artista è comunque la sua raffinata ricerca di interazione tra varie tonalità apparentemente contrastanti eppure sorprendentemente armoniche nel momento in cui vengono accostate nei suoi dipinti.

Nelle opere più neo cubiste emerge anche il lato divertente di Claudio De Gregorio, quel prendersi un po’ in giro che diviene evidente in Autoritratto con angelo custode, in cui la geometricità va a convergere al centro della tela, dove l’artista colloca se stesso vicino a un angelo curiosamente con connotazioni femminili, evidenti dalle labbra, che veglia su di lui senza più nascondersi; tra le righe sembra emergere una velata celebrazione della donna in quest’opera, come a voler sottolineare l’importanza di una presenza costante pronta a essere di sostegno, a dire la sua se è il caso, a essere amorevole ma anche severa se la situazione lo richiede. Il colore giallo dominante enfatizza queste sensazioni, mentre le sfaccettature geometriche costituiscono le tante opzioni, le innumerevoli opportunità dell’esistenza che sono più belle quando condivise.

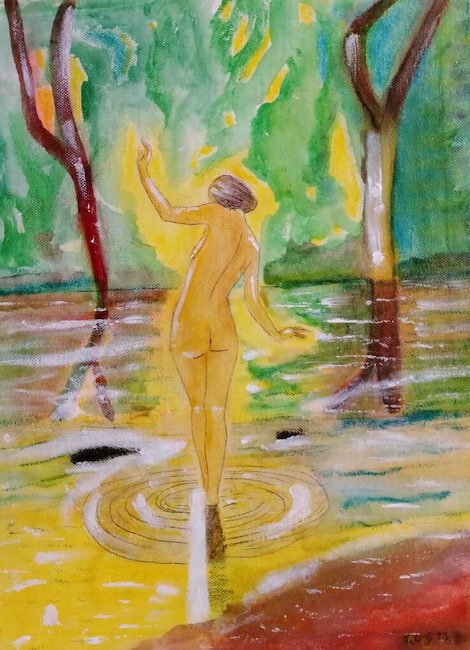

Quando però si sposta verso l’Espressionismo lo sguardo di De Gregorio diviene più poetico, meno ironico certo, ma più vicino alla morbidezza di Marc Chagall e dell’Henri Matisse della maturità, quasi come se più si avvicina alla realtà, maggiore diviene la capacità di lasciarsi trasportare non tanto da un dettaglio quanto dall’insieme, dall’armonia che intravede con lo sguardo e che poi espande, riproducendola, all’intera tela; è questo il caso di Bagno nello stagno, dove la donna ritratta di spalle sembra avvolta da un’aura dorata, come se appartenesse a un mondo magico, romantico, in cui la natura fa da cornice protettiva della sua nudità, intesa forse dall’artista nel senso metaforico dello spogliarsi dai timori e dalle convenzioni per spingersi verso una consapevolezza, una realizzazione di sé che scaturisce esattamente a seguito di un percorso di coraggiosa liberazione dalle proprie paure e dai propri limiti. La luce che la illumina è pertanto quella interiore, non proviene dall’esterno piuttosto scaturisce da quel momento di coraggio che un istante dopo la renderà più forte.

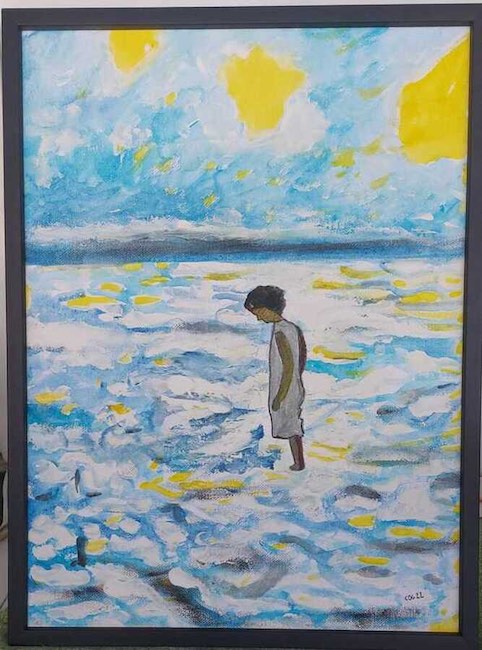

In Il mio mare la natura è quasi assoluta protagonista se non fosse per il personaggio reso piccolo dalla maestosità del paesaggio incontaminato; le pennellate in sfumature di azzurro non riescono a oscurare il giallo dei raggi di sole che si riflettono sulle acque, contribuendo a infondere nell’osservatore una sensazione di nostalgia nei confronti di un momento vissuto, di un paesaggio su cui lo sguardo si è posato e che è intriso di ricordi, del senso di libertà che solo il mare in estate sa suscitare, del profumo di salsedine. L’abilità di De Gregorio sta nel non dare un dettaglio preciso di dove si trovi lo scorcio immortalato, permettendo così a chiunque sia davanti all’opera di immergersi nel proprio ricordo, nel proprio vissuto più o meno lontano eppure, grazie all’evocazione suggerita dall’artista, incredibilmente vicino.

L’opera forse più Fauves tra tutte quelle citate finora è Donna con maglione giallo dove la signora protagonista è immortalata in una fase di attesa, come se da un momento all’altro dovesse sopraggiungere qualcuno, un’amica, un amante, ad alleviare la sua provvisoria solitudine; la posa è rilassata, non c’è trepidazione nel suo sguardo, piuttosto curiosità ma anche serenità, perché in fondo qualunque cosa accadrà sarà frutto di una sua scelta, lo si percepisce dalla posa sicura e dal maglione giallo intenso che denota autostima e capacità, ancora una volta, di non curarsi del giudizio o di qualunque pensiero possano avere gli altri intorno. Il paesaggio circostante è solo un dettaglio, lasciato indefinito dall’artista perché il fulcro del dipinto non può che essere la forte personalità del personaggio femminile che, ancora una volta, sceglie di rendere protagonista.

Claudio De Gregorio ha alle spalle un lunghissimo percorso artistico, cominciato negli anni Novanta del Novecento, nel corso del quale ha esposto in numerose mostre personali e collettive e le sue opere sono inserite in importanti pubblicazioni di arte.

CLAUDIO DE GREGORIO-CONTATTI

Email: claudio.degregorio.1953@gmail.com

Sito web: http://www.cogpittore.it

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100011243467944

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/claudio.degregorio.1953/

The brightly shaded world of Claudio De Gregorio’s Expressionism, when color becomes the protagonist

The creative universe of each artist adapts, or it would be better to say goes along with, the expressive personality often even diverging from what transpires in everyday life; this is because creativity chooses a path of its own, it goes beyond all that veneer of self-control that is necessary to put on in facing life. Here, then, art becomes a means of expressing one’s real essence, that real inner substance hidden but, by virtue of the plastic gesture, able to find its own communicative channel that tells much more than words can. Today’s protagonist finds in chromatic vivacity his favorite language, entrusting colors with the task of explaining, interpreting and highlighting details, feelings and emotions of the characters and places he chooses from time to time to put at the center of the scene.

The first, unexpected rebellion against traditional art, the one whose academic rules and inalienable guidelines for representing the harmony and beauty of human beings as much as of nature had been carefully adhered to until recently, was generated by a group of French artists who gathered in artistic salons to elaborate new theories, new possibilities that even went so far as to overturn all previous schemes. In those very early years of the twentieth century, the Fauves decreed the end of the pictorial tradition as classically intended by emphasizing the importance of the feeling of the executor of the artwork, of his interiority and also of the world told of which the chromaticity was no longer to be pertinent to the observed but necessarily to go along with those emotions that inevitably accompany the human being in every single moment. In order to achieve the interpretive result they sought, they knew they had to give up that harmony, that perfection that had distinguished Realism and Impressionism, the search for perspective, for coloristic nuances, for everything that would somehow distract the eye from the intensity of the narrative. So the members of the movement, which soon evolved to become Expressionism, of which Henri Matisse, Maurice de Vlaminck and André Derain were the major exponents, decided to opt for an intense and often unreal color palette, of not detailing faces and particulars, transforming the characters into projections of their own feelings, and outlining them with an evident graphic stroke as if to contain and at the same time distinguish what belonged to the individual and the surrounding world that conformed to the subject’s emanation.

With the evolution toward Expressionism the intense and sometimes even aggressive tones of the Fauves faded, for by then the breaking point had been reached and change had occurred, yet what was never lost or repudiated was the nonaesthetic approach to the canvas, the futility of faithfully representing reality or focusing on figurative harmony; the graphic stroke, more or less obvious depending on the expressive intent of each adherent to the movement, was preserved, as was the tendency to defy the rules and good taste of the time by laying bare vices and virtues, weaknesses and depravity, anxieties and anguishies. Where Egon Schiele and Edvard Munch chose less aggressive, somber or neutral but still less vivid hues, Emil Nolde and Ernst Ludwig Kirchner instead maintained a strong and impactful color palette to emphasize the message their canvases contained. The artist of Lombard origin, but resident in Pescara for countless years, Claudio De Gregorio, in art COG, chooses the interpretive approach of Expressionism, the one that still predominantly maintains the chromatic legacy of the Fauves, to give his emotional point of view on what catches his gaze, generating original coloristic tones and often with predominance of yellow; because yellow is linked to the image of sun, light, spring, cheerfulness but also elegance and refinement in some cases.

The declination of this chromatic tonality is therefore the common denominator of De Gregorio‘s canvases, which sometimes passes through the decomposition of Neo Cubism to which he mixes the tonal vitality of Orphic Cubism, because in some cases it is necessary to decompose the perceived sensations and recompose them according to the inner order, and only after this operation one can understand the implications; what the artist’s artworks have in common, however, is his refined search for interaction between various seemingly contrasting yet surprisingly harmonious tones as they are juxtaposed in his paintings. In the more neo-cubist artworks also emerges Claudio De Gregorio‘s funny side, that slightly mocking himself that becomes evident in Self-Portrait with Guardian Angel, in which geometricity converges in the center of the canvas, where the artist places himself next to an angel curiously with feminine connotations, evident from the lips, who watches over him without hiding anymore; between the lines there seems to emerge a veiled celebration of women in this painting, as if to emphasize the importance of a constant presence ready to be supportive, to tell her opinion if it’s the case, to be loving but also stern if the situation calls for it. The dominant yellow color emphasizes these feelings, while the geometric facets constitute the many options, the countless opportunities of existence that are most beautiful when shared.

When he moves toward Expressionism, however, De Gregorio‘s gaze becomes more poetic, less ironic it’s ture, but closer to the softness of Marc Chagall and the Henri Matisse of maturity, almost as if the closer he gets to reality, the greater becomes his ability to let himself be carried away not so much by a detail as by the whole, by the harmony he glimpses with his gaze and then expands, reproducing it, to the entire canvas; this is the case with Bathing in the Pond, where the woman portrayed from behind seems enveloped in a golden aura, as if she belonged to a magical, romantic world, in which nature acts as a protective frame for her nudity, understood perhaps by the artist in the metaphorical sense of stripping herself of fears and conventions in order to push herself toward an awareness, a self-realization that arises precisely as a result of a path of courageous liberation from her own fears and limitations. The light that illuminates her is therefore the inner light, not coming from the outside rather springing from that moment of courage that a moment later will make her stronger. In My Sea, nature is almost the absolute protagonist were it not for the character made small by the majesty of the unspoiled landscape; brushstrokes in shades of blue fail to obscure the yellow of the sun’s rays reflecting on the waters, helping to instill in the observer a feeling of nostalgia towards a moment experienced, a landscape on which the gaze has rested and which is steeped in memories, the sense of freedom that only the sea in summer can arouse, the scent of saltiness.

De Gregorio‘s skill lies in not giving a precise detail of where the immortalized glimpse is located, thus allowing whoever is in front of the artwork to immerse himself in his own memory, in his own experience more or less distant and yet, thanks to the evocation suggested by the artist, incredibly close. Perhaps the most Fauves painting of all those mentioned until now is Woman with Yellow Sweater where the lady protagonist is immortalized in a waiting phase, as if at any moment someone, a friend, a lover, should arrive to relieve her temporary loneliness; the pose is relaxed, there is no trepidation in her gaze, rather curiosity but also serenity, because after all whatever will happen will be the result of her own choice, one can sense this from the confident pose and the deep yellow sweater that denotes self-confidence and the ability, once again, not to care about judgment or whatever thoughts others around may have. The surrounding landscape is only a detail, left undefined by the artist because the focus of the painting can only be the strong personality of the female character whom, once again, he chooses to make the protagonist. Claudio De Gregorio has behind him a very long artistic career, which began in the 1990s, during which he has exhibited in numerous solo and group exhibitions and his artworks are included in important art publications.