Lo spostamento inteso come momento di esplorazione di tutto ciò che appartiene a un mondo diverso dal proprio è divenuto mezzo di conoscenza nelle epoche più recenti poiché in precedenza le distanze tra i vari paesi sembravano incolmabili; laddove agli inizi del secolo scorso le culture differenti divennero fonte di ispirazione per l’elaborazione di nuovi stili artistici in cui la contaminazione da parte delle nuove nozioni e scoperte era evidente, nella contemporaneità invece molti creativi hanno piuttosto un approccio curioso, desideroso di scoprire proprio quelle molteplicità culturali che è bello vengano mantenute, indifferentemente dalla spinta verso la globalizzazione che sembra essere l’imperativo dei tempi moderni. Il protagonista di oggi mostra proprio questa inclinazione a riempirsi lo sguardo di tutte le sfaccettature, le differenze di tradizioni, di usi e di costumi che costituiscono la bellezza e l’unicità di ogni luogo, trasferendo sulla tela l’incanto subìto nel momento dell’osservazione e la fascinazione generata dalla folla di persone che a quelle culture diverse appartengono.

La spinta verso l’esplorazione di luoghi esotici e culture lontane da quelle europee cominciò a manifestarsi tra la fine dell’Ottocento e gli inizi del Novecento, quando la navigazione più veloce e agevole e le nuove scoperte tecniche resero il viaggio qualcosa non più appannaggio solo di conquistatori e avventurieri bensì anche dell’emergente borghesia già abituata a spostarsi all’interno del continente europeo; dunque molti artisti cominciarono a mostrare interesse per l’Africa, con le sue maschere, le stilizzazioni rappresentative, che divennero fonte di ispirazione per molti maestri del Novecento come Picasso e Modigliani, o per luoghi più lontani come nel caso di Gauguin, il quale si spinse addirittura fino in Polinesia per entrare in contatto con le culture indigene persino più misteriose rispetto a quelle africane. Da quel momento in avanti la scoperta, la diversità, l’osservazione dell’altro, assunsero un fascino completamente diverso rispetto ai secoli precedenti quando tutto doveva essere convertito alle regole e alle imposizioni occidentali senza considerare che anche altre culture, per quanto opposte, potessero avere un senso tanto valido quanto quello dei conquistatori; dunque l’approccio curioso e rapito di Paul Gauguin fu forse il primo esempio di accettazione e di ammirazione per un mondo incontaminato e puro nelle sue tradizioni, forse più dell’ormai ipocrita e formale società occidentale. Matisse visitando Thaiti in tarda età, trasse ispirazione dalla sua vegetazione per elaborare un nuovo stile pittorico che lo allontantò dalle tematiche Fauves e lo avvicinò a un Espressionismo Astratto arricchito dall’uso del collage; Emil Nolde, il grande espressionista danese, effettuò un lungo viaggio in Nuova Guinea e fu conquistato dai paesaggi e dalle iconografie dell’arte primitiva, introducendo nei suoi dipinti elementi esotici. E ancora Fortunato Depero, esponente del Futurismo, si spostò a occidente, per la precisione a New York, producendo opere dedicate ai paesaggi metropolitani della Grande Mela nel suo particolare stile pittorico. Questi sono solo alcuni dei grandi nomi che hanno fatto del viaggio un arricchimento della propria arte e hanno guardato quei mondi lontani con la neutralità dell’osservatore, senza volerne cambiare nulla bensì subendo il fascino proprio di tutto ciò che appariva completamente divergente dal loro ambiente di appartenenza.

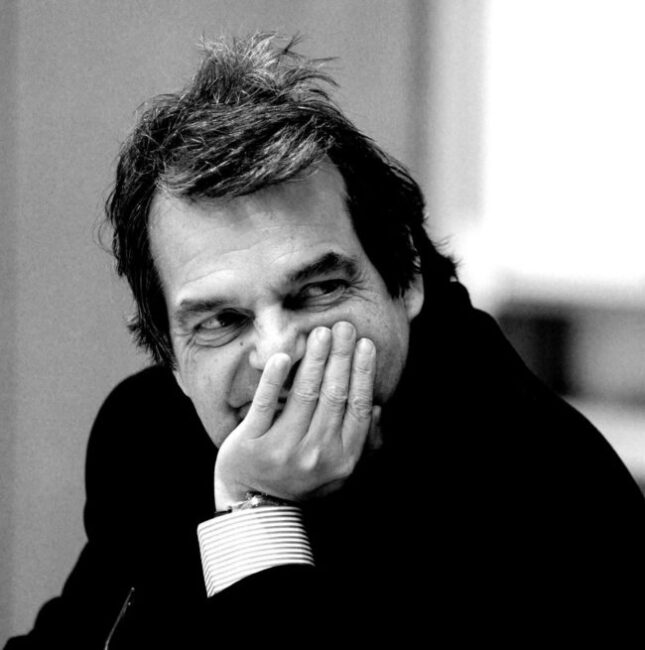

L’artista inglese Mike Ferrell raccoglie questa eredità e la attualizza a quella che nel mondo moderno è una consuetudine incrementata dalla molteplicità delle opzioni per gli spostamenti e anche dai costi accessibili, quella cioè di andare a scoprire e a conoscere qualcosa che senza quei viaggi non potrebbe essere possibile apprendere, dunque il sapore di una quotidianità, di abitudini che si ripetono giornalmente e che appartengono a tutta l’umanità sebbene si manifestino con modalità formali del tutto differenti. Lo stile pittorico scelto da Ferrell è una via a metà tra il Realismo, che si manifesta con maggiore definitezza negli acquarelli poiché questa tecnica gli consente di immortalare il monumento e lo scorcio con velocità finché lo ha davanti agli occhi generando di fatto una vera e propria fotografia manuale, e il Naif con cui riesce perfettamente a infondere nell’osservatore la sensazione di meraviglia provata davanti alla folla che riempie le vie delle città visitate, che frequenta i mercati, i bar, i ristoranti e che suscita la curiosità dell’artista.

Si potrebbe parlare di un nuovo Umanesimo pensando alla pittura di Mike Ferrell perché ciò che emerge in maniera chiara è il suo interesse verso l’essere umano in generale, la sua capacità di aggregazione, il suo desiderio di socializzare, l’esigenza di condividere momenti apparentemente ordinari eppure straordinari se osservati con la sensibile lente dell’artista. La gamma cromatica è sempre luminosa, chiara, la luce è elemento dominante delle tele tanto quanto lo è della vita, ma ciò che colpisce in maniera evidente è la tendenza a nascondere i dettagli dei volti, a non dare un tratto eccessivamente realista, pur riuscendo a mettere in evidenza le espressioni di quei personaggi di cui emerge la soggettività a causa di un atteggiamento particolare, di un abito, di un gesto che li fa uscire dalla moltitudine.

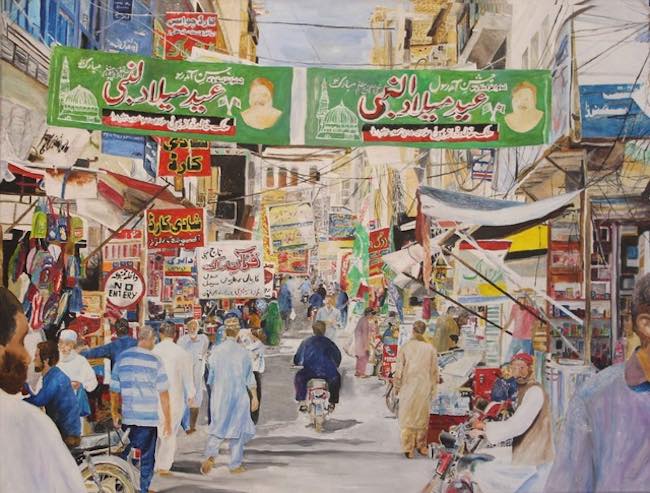

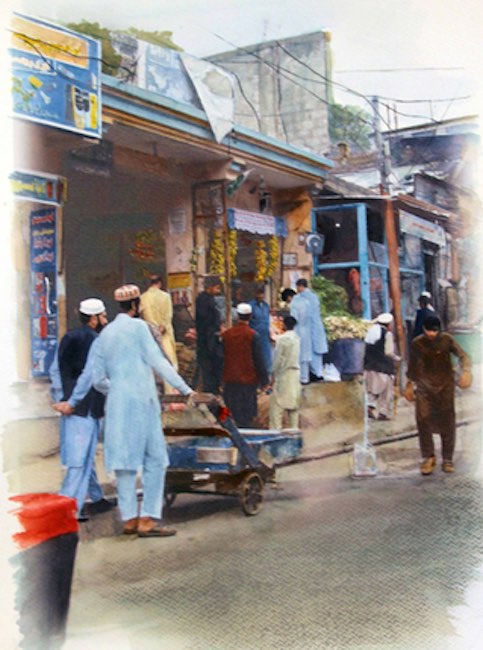

Il suggerimento di Mike Ferrell è che l’attitudine del tutto naturale dell’uomo a voler stare in un gruppo, in un grande insieme dentro cui non sentirsi più solo, non include necessariamente l’annullamento della propria individualità, della propria singolarità anzi, semmai quest’ultima si delinea in modo persino più evidente all’interno di una molteplicità che non riesce, e tutto sommato non vuole, omologare il singolo. Nel riprodurre gli edifici, le strade, i bazar o i bar, il tratto dell’artista diviene invece preciso, meticoloso, incredibilmente dettagliato e reale, per sottolineare quanto la diversità di ciò che appare davanti ai suoi occhi, nel corso dei suoi viaggi di scoperta del mondo, sia fondamentale a determinare le basi culturali delle popolazioni che incontra.

In On the way back from Hunza 4 i dettagli dei negozi ai lati della strada sono curati nei minimi particolari, alla maniera realista, perché in quel frangente il suo istinto creativo lo ha spinto a scattare una vera e propria fotografia artistica di tutto ciò che stava guardando, e perché il fascino esotico del Pakistan era già di per sé sufficientemente coinvolgente per indurre l’osservatore a sognare di quel luogo lontano.

In Tango, la Boca invece l’atmosfera è più sfumata, i dettagli sono lasciati all’intuizione come se fossero solo parzialmente importanti rispetto all’immagine dei due danzatori che sono lì per intrattenere il pubblico; ciò che conquista l’occhio di Mike Ferrell è proprio quell’abitudine dei locali tipici di Buenos Aires di dare agli avventori un assaggio tangibile della cultura locale, della tradizione musicale e danzante che è imprescindibile dall’immagine dell’Argentina stessa.

Nella tela The Eccentric, ancora una volta concentrandosi sulle persone che affollano lo scorcio immortalato decide di concentrare la propria attenzione su un personaggio, protagonista del titolo, eccentrico appunto, fuori dagli schemi, immerso in se stesso e nella lettura nonostante il via vai di persone intorno concentrate a fare sport o ad andare verso il mare; lui con il suo zaino appoggiato sulla panca, il giornale aperto, l’aria rilassata e incurante del giudizio sembra essere un vero gigante dell’individualismo, simbolo della libertà di essere solo ciò che desidera, senza preoccuparsi di cosa la sua scelta possa provocare negli altri. Anche in quest’opera non può non essere notata la predominanza della luce che contraddistingue la produzione artistica di Mike Ferrell, la positività che ne deriva e lo sguardo sorridente verso la vita che traspare da ogni singolo dettaglio e che si armonizza con la gioia di dipingere che ha letteralmente cambiato e arricchito la sua vita; il tema del viaggio dunque è metafora del percorso di evoluzione e di apprendimento che ciascun individuo è chiamato a compiere, fino all’ultimo giorno della propria esistenza, se solo si comprende il bello di questo tipo di approccio.

È forse proprio questo il significato della tela Putting the world right dove un gruppetto di uomini non più giovani sembra trovarsi per discutere sul senso della vita, su ciò che è giusto e cosa è sbagliato, confrontandosi perché consapevoli che è solo attraverso il dialogo e il confronto, che si può continuare a farsi delle domande stimolando il dubbio. Mike Ferrell, attualmente residente in Spagna, ha al suo attivo la partecipazione a molte mostre collettive internazionali a Vienna, Copenaghen, Lisbona, Firenze, Palermo, Venezia, Milano, Eggedal (Norvegia), Parigi, e quattro mostre personali, due in Inghilterra e due in Spagna, riscuotendo grande successo tra il pubblico affascinato dalla sua capacità di farlo viaggiare grazie alle sue opere. Dona tutti i profitti delle vendite per aiutare i bambini rifugiati a ottenere un’istruzione.

MIKE FERREL-CONTATTI

Email: mikehferrel@mail.com

Sito web: www.michaelhferrell.com/

Facebook: www.facebook.com/mike.ferrell.3958

Instagram: www.instagram.com/michaelhferrell/

Between Naif and Realism Mike Ferrell’s fascinating journey into the world, observing the multitude and noticing individuality

Travelling as a moment of exploration of everything that belongs to a world other than one’s own has become a means of knowledge in more recent times because previously the distances between countries seemed unbridgeable; whereas at the beginning of the last century, different cultures became a source of inspiration for the elaboration of new artistic styles in which the contamination by new notions and discoveries was evident, in contemporary times, on the other hand, many creatives have rather a curious approach, eager to discover precisely those cultural multiplicities that it is good to maintain, regardless of the drive towards globalisation that seems to be the imperative of modern times. Today’s protagonist shows precisely this inclination to fill his gaze with all the facets, the differences in traditions, habits and customs that make up the beauty and uniqueness of each place, transferring onto the canvas the enchantment experienced at the moment of observation and the fascination generated by the crowd of people who belong to those different cultures.

The drive towards the exploration of exotic places and cultures far removed from those of Europe began to manifest itself between the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century, when faster and easier navigation and new technical discoveries made travel no longer the prerogative only of conquerors and adventurers, but also of the emerging middle class already accustomed to travelling within the European continent; therefore, many artists began to show interest in Africa, with its masks, its representational stylisations, which became a source of inspiration for many 20th century masters such as Picasso and Modigliani, or for more distant places as in the case of Gauguin, who went as far as Polynesia to come into contact with indigenous cultures even more mysterious than those in Africa. From that moment on, discovery, diversity, the observation of the other, took on a completely different fascination compared to previous centuries when everything had to be converted to western rules and impositions without considering that other cultures, however opposite, could also have as much meaning as the conquerors; thus Paul Gauguin‘s curious and enraptured approach was perhaps the first example of acceptance and admiration for a world that was uncontaminated and pure in its traditions, perhaps more so than the now hypocritical and formal western society. Matisse visited Tahiti late in life and drew inspiration from its vegetation to elaborate a new painting style that distanced him from Fauves themes and brought him closer to an Abstract Expressionism enriched by the use of collage; Emil Nolde, the great Danish Expressionist, made a long trip to New Guinea and was conquered by the landscapes and iconographies of primitive art, introducing exotic elements into his paintings. And again Fortunato Depero, an exponent of Futurism, moved west, to New York to be precise, producing artworks dedicated to the metropolitan landscapes of the Big Apple in his particular pictorial style. These are just a few of the great names that have made travelling an enrichment of their art and have looked at those distant worlds with the neutrality of the observer, not wanting to change anything, but rather undergoing the fascination of everything that appeared completely different from their environment. The English artist Mike Ferrell takes up this legacy and updates it to what in the modern world is a custom increased by the multiplicity of options for travel and also by affordable costs, that is, to go and discover and get to know something that without those journeys it would not be possible to learn, thus the flavour of an everyday life, of habits that are repeated daily and that belong to all of humanity although they manifest themselves in completely different formal ways. The painting style chosen by Ferrell is somewhere between Realism, which manifests itself most clearly in his watercolours, as this technique allows him to immortalise the monument and the foreshortened view as quickly as possible while he has it in front of him thus generating a true hand-held photograph, and the Naïf style, with which he succeeds perfectly in instilling in the observer the feeling of wonder felt before the crowds that fill the streets of the cities he visits, who frequent the markets, bars and restaurants and arouse the artist’s curiosity.

One could speak of a new Humanism when thinking of Mike Ferrell‘s painting because what emerges clearly is his interest in human beings in general, their ability to gather, their desire to socialise, the need to share seemingly ordinary yet extraordinary moments when observed through the sensitive artist’s lens. The chromatic range is always bright, clear, light is a dominant element of the canvases as much as it is of life, but what is most striking is the tendency to conceal the details of the faces, to avoid giving an excessively realistic stroke, while still managing to highlight the expressions of those characters whose subjectivity emerges because of a particular attitude, a dress, a gesture that makes them stand out from the crowd. Mike Ferrell‘s suggestion is that man’s completely natural attitude of wanting to be in a group, in a large whole within which he no longer feels alone, does not necessarily include the annulment of his own individuality, of his own singularity, on the contrary, if anything, the latter becomes even more evident within a multiplicity that does not succeed, and does not want to homologate the individual. Instead, in reproducing buildings, streets, bazaars or bars, the artist’s stroke becomes precise, meticulous, incredibly detailed and real, to emphasise how much the diversity of what appears before his eyes, in the course of his voyages of discovery of the world, is fundamental in determining the cultural bases of the populations he encounters.

In On the way back from Hunza 4, the details of the shops on the sides of the street are taken care of to the tiniest detail, in the realist manner, because at that juncture his creative instinct drove him to take a true artistic photograph of everything he was looking at, and because the exotic charm of Pakistan was in itself sufficiently enthralling to induce the observer to dream of that faraway place. In Tango, la Boca, on the other hand, the atmosphere is more nuanced, the details are left to intuition as if they were only partially important with respect to the image of the two dancers who are there to entertain the public; what captures Mike Ferrell‘s eye is precisely that habit of the typical Buenos Aires clubs of giving customers a tangible taste of the local culture, of the musical and dancing tradition that is inseparable from the image of Argentina itself. In the canvas The Eccentric, once again concentrating on the people who crowd the immortalised glimpse, he decides to focus his attention on a character, the protagonist of the title, eccentric in fact, unconventional, immersed in himself and in reading despite the hustle and bustle of people around concentrated on doing sports or going to the sea; he with his backpack resting on the bench, his newspaper open, his air relaxed and heedless of judgement seems to be a true giant of individualism, a symbol of the freedom to be only what he wants, without worrying about what his choice might provoke in others.

In this painting too, one cannot fail to notice the predominance of light that distinguishes Mike Ferrell‘s artistic production, the positivity that derives from it and the smiling gaze towards life that transpires from every single detail and that harmonises with the joy of painting that has literally changed and enriched his life; the theme of the journey is therefore a metaphor for the path of evolution and learning that each individual is called upon to undertake, right up to the last day of his existence, if only one understands the beauty of this approach. This is perhaps precisely the meaning of the canvas Putting the world right, where a small group of men who are no longer young seem to find themselves discussing the sense of life, what is right and what is wrong, confronting each other because they are aware that it is only through dialogue and confrontation that one can continue to ask questions, stimulating doubt. Mike Ferrell, currently living in Spain, has to his credit the participation in many international group exhibitions in Vienna, Copenhagen, Lisbon, Florence, Palermo, Venice, Milan, Eggedal (Norway), Paris, and four solo exhibitions, two in England and two in Spain, gaining great success among the public fascinated by his ability to make them travel through his artworks. He gives all profits from sales to help refugee children gain an education.