A volte la realtà ha bisogno di essere guardata da posizioni differenti da quelle ordinarie, necessita di mettersi su un livello nuovo in virtù del quale riuscire a fornire all’osservatore di un’opera una prospettiva inedita e al tempo stesso comprensibile per poterne fruire al meglio; alcuni artisti adottano questo tipo di approccio trasformandolo sulla base della propria intuitività e personalità espressiva, e in alcuni casi anche per rendere più divertente e attuale ciò che appartiene alla tradizione figurativa e per ironizzare sulle piccole manie e abitudini attuali. Nella sua serie neocubista Ray Piscopo mostra una spiccata capacità prismatica nei confronti dell’osservato e dà una personale versione sia di alcuni simboli storici appartenenti all’iconografia tradizionale, e sia della quotidianità intorno a sé che attraverso questo particolare filtro pittorico sfaccettato assume un fascino attrattivo in virtù della decisa e vivida gamma cromatica.

Nella fase artistica dei primi decenni del Ventesimo secolo, i creativi si trovarono ad avere a disposizione intuizioni e possibilità pittoriche elaborate negli anni precedenti che avevano dato il via a quel processo di innovazioni in virtù del quale era stato possibile generare nuove filosofie espressive; nel momento in cui il tema della frammentazione delle immagini si consolidò, divenne oggetto di analisi e di approfondimento da parte di tutto quel gruppo di artisti che pur volendo ancora restare attaccati all’immagine visibile volevano darne un punto di vista differente, nuovo e al di fuori di ogni schema precedente. Fu così che da un lato il Futurismo, con la sua ricerca della rappresentazione della velocità del progresso di quei primi anni del Novecento e nella fiducia nei confronti del futuro che si generava grazie a innovazioni tecnologiche in grado di migliorare la vita quotidiana, e dall’altro il Cubismo con la tendenza a pensare al di fuori degli schemi per dare una visione simultanea di tutto ciò che veniva colto dallo sguardo eliminando la terza dimensione e ponendo sullo stesso piano tutte le sfaccettature dell’osservato, fecero della scomposizione uno dei temi più interessanti e pioneristici di quel periodo. Fu però il Cubismo, grazie all’eclettica e prorompente personalità del suo massimo rappresentante, Pablo Picasso, a lasciare una scia più profonda nel corso della storia dell’arte moderna, poiché egli seppe mescolare differenti influenze tra cui l’Africanismo, visibile nel capolavoro Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, considerato il manifesto del movimento, dove i volti delle donne sono ispirati alle maschere tribali africane. La grandezza delle opere di Picasso, e anche di Georges Braque, era contraddistinta da una gamma cromatica tenue, terrosa, quasi bicroma in alcune opere, per sottolineare ed enfatizzare quella suddivisione geometrica base ed essenza stessa del Cubismo; tuttavia, come d’altronde sempre è successo nel corso della storia, vi fu un esponente del movimento, lo spagnolo Juan Gris, che decise di distaccarsi dalle regole riconosciute, e associò alla scomposizione tonalità più forti e vivaci, che invece di distrarre dalla linea principale della suddivisione geometrica delle immagini, in realtà la rafforzò generando un’attrazione da parte del fruitore che prima si concentra sui colori e poi indugia sui dettagli frammentati della composizione. Fu esattamente questa rivalutazione della gamma cromatica piena e intensa a indurre più tardi i coniugi Robert e Sonia Delaunay a teorizzare le linee guida del Cubismo Orfico, in cui il contatto con l’osservato veniva completamente perduto, tendendo così verso l’informale, per far emergere la magia del colore.

La linea produttiva di Ray Piscopo che andremo ad approfondire tra poco si ispira al Cubismo tradizionale di Pablo Picasso nella scelta dei soggetti rappresentati e nella loro descrizione, ma poi tende in modo assoluto verso il colore superando persino le caratteristiche tonali di Juan Gris per spostarsi verso un utilizzo Pop vicino alla vivacità di Ugo Nespolo; il risultato è un linguaggio pittorico innovativo e anche divertente, poiché attraverso la sua rivisitazione può affrontare temi più classici, come un’inedita interpretazione di alcune rappresentazioni tipiche dell’arte del passato, oppure momenti attuali, frammenti di vita o di comportamenti tipici dell’essere umano contemporaneo, tutti sotto la spinta ironica a sorridere di tutto ciò che appartiene alla realtà perché in fondo è questo il modo migliore per vivere l’esistenza.

Lo sguardo giocoso di Ray Piscopo diviene dunque filtro per dare una versione differente dell’osservato, per attuare quella frammentazione necessaria a mettere disordine e al contempo a porre l’attenzione su dettagli che diversamente rimarrebbero ignorati, nascosti dentro l’immagine complessiva; non solo, la rinuncia assoluta alla terza dimensione gli consente di mettere sullo stesso livello e contemporaneamente più lati dei personaggi, caratteristica questa tipica del Cubismo, frapponendovi anche frammenti di oggetti che così vanno a mescolarsi come se non vi fosse distinzione, come a sottolineare quanto ogni piccolo particolare possa avere rilevanza nel contesto di una scena che attrae l’attenzione al punto di volervisi soffermare.

La scelta dei colori corre verso quell’intensità Fauves necessaria a infondere un’apparenza Pop alle opere, riferimento questo a cui Ray Piscopo raramente riesce a rinunciare proprio per l’attitudine positiva e sorridente che lo contraddistingue e che gli permette di guardare ogni cosa con la medesima sorpresa meraviglia che appartiene ai giovani.

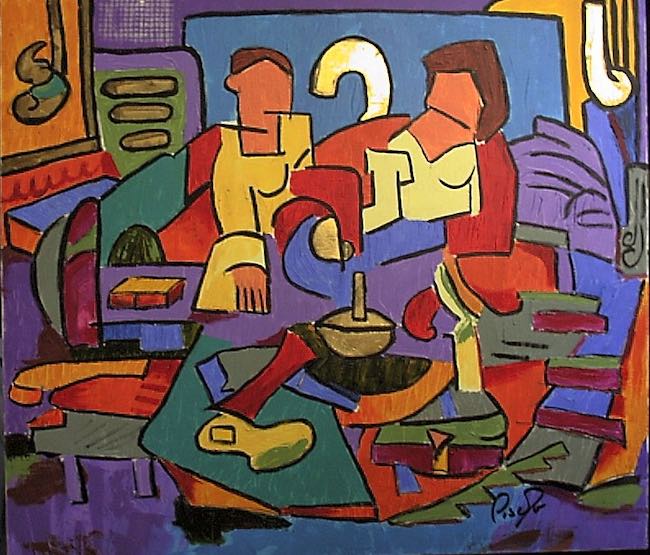

Nella tela Dialogue 2 viene messo in evidenza il senso della composizione, cioè quell’interfacciarsi tra due persone che desiderano trascorrere il proprio tempo insieme, raccontandosi intimamente oppure al contrario semplicemente conversando su temi poco personali; ciò su cui mette l’accento l’artista è l’importanza dell’incontrarsi, nel confrontarsi di persona in un’epoca in cui l’imperativo sembra essere quello di nascondersi dietro lo schermo di un telefonino o di un computer. In quest’opera i due protagonisti sono uno di fronte all’altro, si guardano e non fanno caso a tutto ciò che ruota loro intorno eppure è difficile intuire se siano completamente sinceri, soprattutto la frammentazione del volto dell’uomo sembra suggerire la presenza di maschere funzionali a non rivelare tutto di sé; ecco dunque emergere l’altra visione di Ray Piscopo, accennata più sottilmente, su quanto sia difficile nell’era contemporanea essere davvero se stessi persino quando ci si incontra, rendendo così superfluo quel rifugiarsi dentro la distanza della tecnologia che non fa altro che isolare le persone impedendo la socializzazione, sincera o meno che sia.

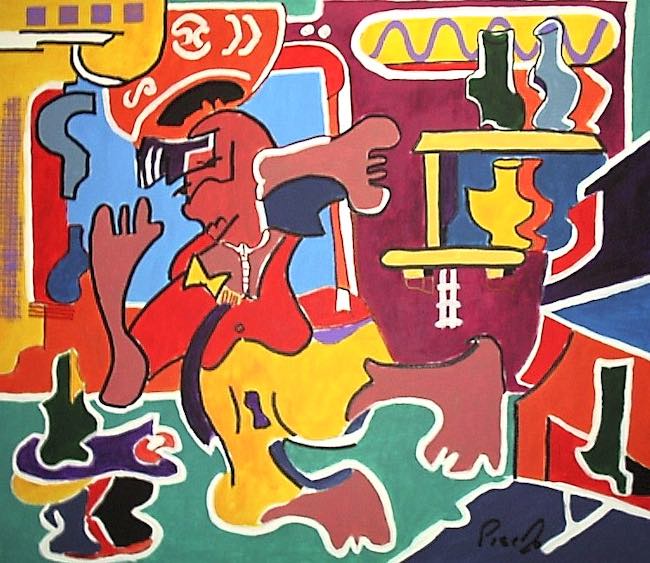

In The drunk la frammentazione è più accentuata e si propaga fino al corpo dell’uomo per enfatizzare il suo stato di ebbrezza, per sottolineare la sua difficoltà a mantenere l’equilibrio; non c’è giudizio da parte di Ray Piscopo, piuttosto il desiderio di mettere in luce una delle sfaccettature dell’esistenza, un eccesso che può essersi verificato più o meno nella vita di chiunque e che diviene così pura rappresentazione divertita e irriverente di qualcuno che ha solo scelto di trascorrere una serata più allegra del solito. Le gambe e la postura del corpo sono completamente scomposte, quasi in bilico all’interno del locale di cui vasi, bottiglie e tavolini costituiscono un contorno funzionale a infondere il senso di instabilità dell’uomo, mentre i colori sono forti, intensi, per sottolineare la vivacità dell’ambiente in cui si è trovato a trascorrere quei momenti.

Il dipinto Modern day Saints è forse l’opera in cui l’ironia di Ray Piscopo è più evidente, in cui emerge quella capacità di andare oltre il visibile attraverso la fantasia e trasformare una coppia che si potrebbe definire strana in qualcosa di quasi mistico, perché in fondo il loro essere fuori dagli schemi può essere considerato coraggioso tanto quanto in tempi passati erano guardati con diffidenza alcuni personaggi che hanno fatto del bene o hanno portato messaggi positivi; l’indifferenza nei confronti di chiunque li guardi e la naturalezza con la quale affrontano la loro quotidianità fatta di scelte e di decisioni che li conduce a essere a volte persino emarginati dalla società, fa di loro potenziali portatori di un rinnovato messaggio di accettazione, di tolleranza, di invito a prendere gli altri per come sono e per cosa hanno da dire, senza curarsi di un aspetto che potrebbe essere considerato eccentrico o singolare. L’anticonformismo diviene così invito a mantenere viva la propria individualità senza conformarsi al pensiero comune per sentirsi accettati.

Dunque in questa serie di lavori Ray Piscopo mostra una forte capacità interpretativa e di personalizzazione di uno stile complesso e analitico come il Cubismo, così come l’abilità di mescolarlo ad altri linguaggi artistici per assecondarli al suo istinto creativo.

RAY PISCOPO-CONTATTI

Email: piscopoart@gmail.com

Sito web: www.piscopoart.com/

Facebook: www.facebook.com/ray.piscopo

Instagram: www.instagram.com/raypiscopo/

Ray Piscopo’s NeoCubism, when observation of the contemporaneity mixes with the fascination of iconographic traditions

Sometimes reality needs to be looked at from different positions than the ordinary ones, it needs to be placed on a new level by virtue of which it is possible to provide the observer of an artwork with an unprecedented and at the same time comprehensible perspective in order to be able to enjoy it at its best. Some artists adopt this type of approach, transforming it on the basis of their own intuitiveness and expressive personality, and in some cases also to make what belongs to the figurative tradition more amusing and topical, and to make fun of the small foibles and habits of today. In his neo-Cubist series, Ray Piscopo shows a prismatic ability towards the observed and gives a personal version both of certain historical symbols belonging to traditional iconography and of the everyday life around him, which through this particular multifaceted pictorial filter takes on an attractive charm by virtue of the decisive and vivid colour range.

In the artistic phase of the first decades of the 20th century, creatives found themselves with intuitions and pictorial possibilities elaborated in the previous years that had triggered that process of innovations by virtue of which it had been possible to generate new philosophies of expression; as the theme of the fragmentation of images consolidated, it became the object of analysis and in-depth study by that entire group of artists who, while still wishing to remain attached to the visible image, wanted to give it a different, new point of view, outside of any previous scheme. Thus it was that on the one hand Futurism, with its quest for the representation of the speed of progress in those early years of the 20th century and its confidence in the future generated by technological innovations capable of improving everyday life, and on the other hand Cubism, with its tendency to think outside the box to give a simultaneous vision of everything that was caught by the gaze eliminating the third dimension and placing all the facets of the observed on the same plane, made decomposition one of the most interesting and pioneering themes of that period. However, it was Cubism, thanks to the eclectic and bursting personality of its greatest representative, Pablo Picasso, that left the deepest wake in the history of modern art, as he was able to mix different influences including Africanism, visible in the masterpiece Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, considered the movement’s manifesto, where the women’s faces are inspired by African tribal masks. The grandeur of Picasso‘s works, and also those of Georges Braque, was marked by a soft, earthy, almost bichromatic colour palette in some paintings, to emphasise and underline that geometric subdivision that is the basis and very essence of Cubism; however, as has always been the case throughout history, there was one exponent of the movement, the Spanish Juan Gris, who decided to break away from the recognised rules, and associated the decomposition with stronger, more vivid tones, which instead of distracting from the main line of the geometric subdivision of the images, actually reinforced it by generating an attraction on the part of the viewer who first focuses on the colours and then lingers on the fragmented details of the composition.

It was precisely this reappraisal of the full and intense colour range that later prompted Robert and Sonia Delaunay to theorise the guidelines of Orphic Cubism, in which contact with the observed was completely lost, tending towards the informal, in order to bring out the magic of colour. Ray Piscopo‘s production line that we will go into in more detail in a moment is inspired by the traditional Cubism of Pablo Picasso in the choice of the subjects represented and their description, but then tends absolutely towards colour, even surpassing the tonal characteristics of Juan Gris to move towards a Pop use close to the vivacity of Ugo Nespolo; the result is a pictorial language that is both innovative and also amusing, since through its revisitation it can deal with more classical themes, such as an unprecedented interpretation of certain representations typical of the art of the past, or current moments, fragments of life or behaviour typical of contemporary human beings, all under the ironic impulse to smile at everything that belongs to reality because after all this is the best way to experience existence. Ray Piscopo‘s playful gaze thus becomes a filter to give a different version of the observed, to implement that fragmentation necessary to create disorder and at the same time to draw attention to details that would otherwise remain ignored, hidden within the overall image; not only that, the absolute renunciation of the third dimension allows him to place several sides of the characters on the same level at the same time, a characteristic typical of Cubism, placing fragments of objects among them, which thus blend together as if there were no distinction, as if to emphasise how every small detail can have relevance in the context of a scene that attracts attention to the point of wanting to dwell on it.

The choice of colours runs towards that Fauves intensity necessary to infuse the artworks with a Pop appearance, a reference that Ray Piscopo rarely manages to renounce precisely because of the positive and smiling attitude that distinguishes him and allows him to look at everything with the same surprised wonder that belongs to the young. In the canvas Dialogue 2, is put in evidence the meaning of the composition, that is the interface between two people who wish to spend their time together, telling each other intimately or, on the contrary, simply conversing about non-personal topics; what the artist underlines is the importance of meeting, of confronting each other in person in an era in which the imperative seems to be to hide behind the screen of a mobile phone or computer. In this painting, the two protagonists are facing each other, they look and pay no attention to everything that revolves around them, and yet it is difficult to guess whether they are completely sincere, especially the fragmentation of the man’s face seems to suggest the presence of masks functional to not reveal everything about themselves; here, then, emerges Ray Piscopo‘s other vision, hinted at more subtly, on how difficult it is in the contemporary era to be truly oneself even when one meets, thus rendering superfluous that refuge within the distance of technology that does nothing but isolate people, preventing socialisation, whether sincere or not. In The drunk, the fragmentation is more accentuated and spreads as far as the man’s body to emphasise his state of intoxication, to underline his difficulty in maintaining equilibrium; there is no judgement on Ray Piscopo‘s part, rather a desire to highlight one of the facets of existence, an excess that may have occurred more or less in anyone’s life and which thus becomes a purely amused and irreverent representation of someone who has merely chosen to spend a more cheerful evening than usual. The legs and the posture of the body are completely disjointed, almost hovering inside the room, of which vases, bottles and tables constitute a functional outline to instil a sense of instability in the man, while the colours are strong, intense, to emphasise the liveliness of the environment in which he found himself spending those moments. The painting Modern day Saints is perhaps the work in which Ray Piscopo‘s irony is most evident, in which emerges that ability to go beyond the visible through imagination and transform a couple that could be defined as strange into something almost mystical, because after all, their being outside the box can be considered as courageous as in times past some people who did good or brought positive messages were looked upon with distrust; indifference towards anyone who looks at them and the naturalness with which they face their everyday life made up of choices and decisions, which leads them to be sometimes even marginalised by society, makes them potential bearers of a renewed message of acceptance, tolerance, an invitation to take others as they are and for what they have to say, without caring about an aspect that could be considered eccentric or singular. Non-conformism thus becomes an invitation to keep one’s individuality alive without conforming to common thinking in order to feel accepted. Thus, in this series of artworks, Ray Piscopo shows a strong capacity for interpretation and personalisation of a complex and analytical style such as Cubism, as well as the ability to mix it with other artistic languages in order to indulge his creative instincts.