Il fascino del passato più lontano ha segnato una parte significativa dell’arte moderna e anche della contemporanea in cui molti creativi sentono il bisogno di guardare indietro per trovare le proprie radici e attingere ad antiche tradizioni espressive, a un intento rappresentativo primordiale in grado di costituire una solida base a cui ispirarsi per cercare il modo di vivere un presente più sereno, meno complicato e meno orientato al distacco con quella naturalezza che invece apparteneva agli avi dell’umanità. La protagonista di oggi modella l’argilla, suo materiale prediletto, per compiere quel ritorno a un passato storico in cui mescola stili e simboli dando vita a un suo personale linguaggio.

Intorno alla fine del Diciannovesimo secolo in Europa, grazie all’evoluzione nella costruzione di navi e di ferrovie che facilitava gli spostamenti di nazione e spesso anche di continente, si sviluppò un forte interesse per culture diverse, antiche e primordiali che erano ancora fortemente presenti nei paesi considerati meno civilizzati come l’Africa, l’Oriente, l’Oceania, e tutto ciò che si nascondeva nelle tradizioni indigene che avevano costituito le uniche comunità organizzate in quei luoghi sconosciuti, così come anche nelle emergenti Americhe. Quell’interesse, oltre a generare il desiderio da parte della nuova borghesia di avere in casa pezzi originali di quei paesi lontani, si trasformò in una tendenza artistica, denominata Primitivismo, a cui aderirono molti importanti maestri dei primi anni del Novecento, partendo dai maggiori esponenti dell’Espressionismo come Amedeo Modigliani e Paul Gauguin, che si trasferì definitivamente a Tahiti per non perdere il contatto con la natura e la spontaneità conosciute nel suo viaggio di ricerca, per finire al Cubismo di Pablo Picasso il quale si ispirò alle maschere tribali africane per delineare i volti dei personaggi protagonisti delle sue opere. Ma il fascino esercitato dalle civiltà indigene non si limitò a essere un fenomeno di moda nel periodo a cavallo tra fine Ottocento e inizi Novecento, tutt’altro, entrò nella cultura comune costituendo un punto di riferimento, un modello a cui ispirarsi anche per molti movimenti artistici che si costituirono negli anni seguenti come la Street Art, in particolar modo quella più legata al graffitismo di Keith Haring e di Jean-Michel Basquiat i quali, ciascuno con il proprio personale linguaggio, indicavano quella primitiva semplicità come un modo per giungere diretti alle persone, per gridare il proprio disagio all’interno di una società che tendeva a rifiutare chiunque non volesse adattarsi alle regole imposte dalle evoluzioni di quel periodo, chiunque decidesse o non potesse fare a meno di sentirsi diverso considerando pertanto la semplicità espressiva come l’unico modo per rappresentare quella sensazione di disadattamento. Ma anche la Brut Art, a suo modo espressione di un altro mondo emarginato, quello dei malati mentali ricoverati negli ospedali psichiatrici che attraverso l’arte trovavano una dimensione per salvarsi dal buio delle loro menti, attinse ai segni, alle immagini basiche dei graffiti primitivi e delle maschere indigene dando vita a un genere artistico di nicchia ma fortemente rappresentativo di un tipo di espressività spontanea, ingenua, inconsapevole di ogni regola stilistica, estetica ed esecutiva che invece aveva costituito la base di tutta l’arte precedente al Novecento, più accademica, più oggettivamente rivolta la bello ma anche meno impregnata del mondo delle sensazioni che invece poteva emergere attraverso un approccio più primordiale.

L’artista canadese Sylvie Pronovost non solo abbraccia in pieno la filosofia del Primitivismo che mescola sapientemente alla Brut Art e ai simboli delle popolazioni indigene del nord del continente americano, ma ne riprende anche i materiali con cui realizzare le sue sculture, le sue anfore e i suoi piatti in cui emerge un profondo legame con le origini del passato dell’umanità e con la malia che esercita su di lei quel mondo misterioso, deforme quasi eppure perfettamente in grado di esprimere le sensazioni che da sempre appartengono all’uomo, persino quando il suo linguaggio non era articolato né strutturato.

Nelle sue opere, che possono anche essere appese esattamente come nel caso delle maschere tribali e delle tavole che contenevano calendari, messaggi esistenziali, consigli saggi sul vivere, o rappresentazioni figurative delle divinità politeiste a cui i primitivi si votavano, emerge un approccio simbolico poiché i titoli entrano in contrasto ma al tempo stesso in armonia superiore con le immagini, attribuendo a ciascuna icona appartenente alla cultura tribale un significato filosofico più profondo. O forse al contrario, ciò che Sylvie Pronovost intende sottolineare è proprio quel pensiero avanzato appartenente a civiltà tanto antiche eppure incredibilmente aperte nella connessione con le energie sottili che da sempre ruotano intorno all’uomo.

Probabilmente il suo è uno sguardo nostalgico e al tempo stesso consapevole dalla grandezza e della profondità di contenuti in un periodo in cui l’essere umano aveva solo se stesso, le persone che facevano parte della sua vita, la sua tribù, in pace e senza tutte quelle ambizioni e quella corsa al successo e all’accumulo di denaro che contraddistingue invece lo stile di vita attuale.

La scultura Sapiens riproduce il fronte e il retro di uno dei saggi, spesso identificati con il nome di stregoni, sciamani, curatori, i vecchi delle tribù che lasciavano e tramandavano la loro sapienza a tutti gli altri, costituendo per questo un punto di riferimento fondamentale in grado di spiegare il corpo umano e il suo funzionamento, è questo che rappresenta il disegno nel retro concavo della scultura, mentre il fronte infonde una sensazione di rispetto, di autorevolezza.

In Dèesses de la fertilité (Dee della fertilità), la Pronovost celebra la figura femminile intesa come generatrice di vita, come rifugio sicuro dalle vicissitudini della vita, ed è proprio per questo che ne evidenzia le forme, la rotondità, trasformandola non tanto in simbolo sessuale piuttosto in rassicurante figura materna a cui rivolgersi in caso di bisogno perché sempre presente e pronta a dispensare carezze e consigli.

Nell’opera Cible (Bersaglio), l’artista enfatizza l’importanza primitiva della capacità difensiva, della necessità di allenare l’abilità a combattere senza la quale nell’epoca in cui non esistevano la diplomazia e il dialogo e tutto era affidato alla forza e alla superiorità nella lotta che potevano fare la differenza tra sopravvivere o soccombere, tra il proteggere gli anziani, le donne e i bambini della tribù o permettere all’antagonista di conquistare terreno e appropriarsi di tutto. Forse quest’opera rappresenta un parallelismo con la società contemporanea dove malgrado il progresso, malgrado l’apparente evoluzione nel campo della conoscenza ma anche della capacità di dialogo, non sembrano esserci stati molti cambiamenti da questo punto di vista perché l’uomo non ha mai smesso di mostrare i muscoli, di cercare un antagonista contro cui combattere e su cui vincere.

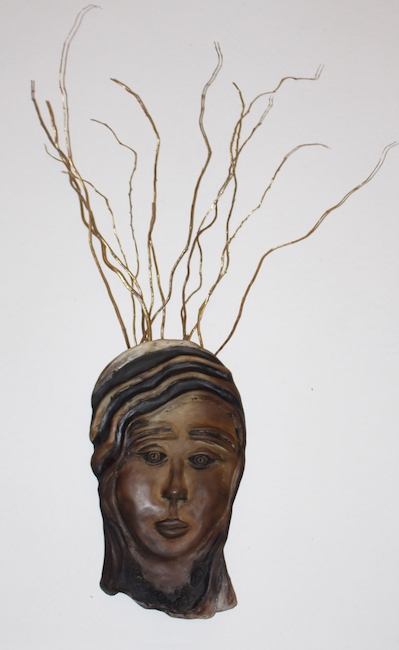

Infine la maschera L’Autochtone (Il nativo) si avvicina all’iconografia delle tribù indigene nordamericane che non sono poi così tanto lontane dalle rappresentazioni figurative degli Atzechi, altro popolo pre-colombiano insediato nel Messico settentrionale, lasciando intuire forse una connessione, una contaminazione o addirittura uno stesso ramo originario di tutte le grandi civiltà del passato, da quelle aborigene australiane, a quelle africane per finire a quelle appunto americane. Il volto rappresenta la serenità con cui affrontavano la vita le popolazioni antiche ed è ornato da quei segni con cui i nativi truccavano i volti sulla base dell’evento con cui dovevano misurarsi, la battaglia, una festa, la celebrazione, ogni circostanza aveva un rituale prestabilito a cui tutti si adeguavano; Sylvie Pronovost sembra voler sottolineare la bellezza di quelle abitudini, di quei riti semplici eppure chiari, facilmente comprensibili da tutti e legati alle tradizioni comuni di ciascuna piccola comunità. Sylvie Pronovost tiene attualmente corsi di scultura in argilla per adulti e bambini, è stata coordinatrice di mostre e tesoriere del Centro d’Arte Contemporanea di Outaouais da cui ha anche ricevuto il Premio de l’Outaouais alle Culturiades della Fondation pour les arts, les lettres et la culture (FALCO), ha al suo attivo numerose mostre nello stato del Quebec e all’estero, è membro onorario del Consiglio della Scultura del Quebec.

SYLVIE PRONOVOST-CONTATTI

Email: sylvielamauricienne@hotmail.com

Sito web: https://www.culturelaurentides.com/membres/sylvie-pronovost-2/

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/sylvie.pronovost.545

Sylvie Pronovost’s clay artworks between Primitivism, Brut Art and native North American symbols

The fascination with the distant past has marked a significant part of modern and contemporary art, in which many creatives feel the need to look back to find their roots and draw on ancient expressive traditions, on a primordial representative intent capable of constituting a solid base from which to draw inspiration in order to seek a way to live a more serene present, less complicated and less oriented towards detachment with the naturalness that belonged to humanity’s ancestors. Today’s protagonist models clay, her favourite material, to make that return to a historical past in which she mixes styles and symbols, giving life to her own personal language.

Around the end of the nineteenth century in Europe, thanks to developments in ship and railway construction that facilitated the movement of nations and often even continents, a strong interest developed in different, ancient and primordial cultures that were still strongly present in countries considered less civilised such as Africa, the Orient, Oceania, and all that was hidden in the indigenous traditions that had formed the only organised communities in those unknown places, as well as in the emerging Americas. That interest, as well as generating a desire on the part of the new bourgeoisie to have original pieces from those distant countries in their homes, turned into an artistic trend, called Primitivism, to which many important masters of the early 20th century adhered, starting with the major exponents of Expressionism such as Amedeo Modigliani and Paul Gauguin, who moved permanently to Tahiti so as not to lose contact with the nature and spontaneity he had encountered on his research trip, to finish with the Cubism of Pablo Picasso, who drew inspiration from African tribal masks to outline the faces of the characters in his artworks. But the fascination exercised by the indigenous civilisations was not limited to being a fashionable phenomenon in the period between the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century.

On the contrary, it entered into common culture, becoming a point of reference, a model that inspired many artistic movements that emerged in the following years, such as Street Art, especially the one more closely linked to the graffiti of Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat, each with their own personal language, indicated that primitive simplicity as a way of reaching people directly, of shouting out their discomfort within a society that tended to reject anyone who did not want to adapt to the rules imposed by the evolutions of that period, anyone who decided or could not help feeling different, thus considering expressive simplicity as the only way to represent that feeling of maladjustment. But even Brut Art, in its own way an expression of another marginalised world, that of the mentally ill in psychiatric hospitals who found a dimension through art to save themselves from the darkness of their minds, drew on the signs, the basic images of primitive graffiti and indigenous masks, giving rise to a niche artistic genre but strongly representative of a type of spontaneous expressiveness, ingenuous, unaware of any stylistic, aesthetic or executive rules, which had instead constituted the basis of all art prior to the 20th century, more academic, more objectively aimed at beauty but also less imbued with the world of sensations that could instead emerge through a more primordial approach. The Canadian artist Sylvie Pronovost not only fully embraces the philosophy of Primitivism, which she skilfully mixes with Brut Art and the symbols of the indigenous peoples of the North American continent, but she also uses its materials to make her sculptures, amphorae and plates which reveal a deep connection with the origins of mankind’s past and with the enchantment exerted on her by that mysterious world, almost deformed yet perfectly capable of expressing the feelings that have always belonged to man, even when his language was neither articulated nor structured.

In her artworks, which can also be hung up exactly as in the case of the tribal masks and plates that contained calendars, existential messages, wise advice on living, or figurative representations of the polytheistic divinities to which the primitives devoted themselves, a symbolic approach emerges, as the titles enter into contrast but at the same time into superior harmony with the images, attributing to each icon belonging to the tribal culture a deeper philosophical meaning. Or perhaps, on the contrary, what Sylvie Pronovost wants to emphasise is precisely that advanced thinking belonging to civilisations that are so ancient yet incredibly open in their connection with the subtle energies that have always revolved around man. It is probably a nostalgic and at the same time conscious of the greatness and depth of content of a time when the human being had only himself, the people in his life, his tribe, in peace and without all the ambition and the race for success and the accumulation of money that characterises today’s lifestyle. The Sapiens sculpture reproduces the front and back of one of the wise men, often identified as wizards, shamans, curators, the elderly of the tribes who left and passed on their knowledge to all the others, thus constituting a fundamental point of reference able to explain the human body and how it works. This is what the drawing on the concave back of the sculpture represents, while the front infuses a feeling of respect, of authority. In Dèesses de la fertilité (Goddesses of fertility), Pronovost celebrates the female figure as the generator of life, as a safe refuge from the vicissitudes of life, and it is precisely for this reason that she emphasises its forms, its roundness, transforming it not so much as a sexual symbol but rather as a reassuring maternal figure to turn to in case of need because she is always present and ready to dispense caresses and advice. In the artwork Cible (Target), the artist emphasises the primitive importance of the defensive capacity, of the need to train the ability to fight without which, at a time when diplomacy and dialogue did not exist and everything was entrusted to strength and superiority in the fight that could make the difference between surviving or succumbing, between protecting the elders, women and children of the tribe or allowing the antagonist to conquer the land and take possession of everything. Perhaps this artwork represents a parallelism with contemporary society where, despite the progress, despite the apparent evolution in the field of knowledge but also in the capacity for dialogue, there does not seem to have been much change from this point of view because man has never stopped flexing his muscles, looking for an antagonist to fight and win over.

Lastly, the mask L’Autochtone (The Native) is close to the iconography of the indigenous North American tribes, which are not so far removed from the figurative representations of the Aztecs, another pre-Columbian people who settled in northern Mexico, perhaps suggesting a connection, a contamination or even a single original branch of all the great civilisations of the past, from the Australian aborigines to the Africans and finally to the Americans. The face represents the serenity with which the ancient populations faced life and is adorned with those signs with which the natives made up their faces according to the event they had to face, a battle, a festival, a celebration, every circumstance had a pre-established ritual to which everyone conformed; Sylvie Pronovost seems to want to underline the beauty of those habits, of those simple yet clear rituals, easily understood by all and linked to the common traditions of each small community. Sylvie Pronovost currently holds clay sculpture classes for adults and children, she has been exhibition coordinator and treasurer of the Outaouais Centre for Contemporary Art, from which she also received the Outaouais Prize for Culturiades from the Fondation pour les arts, les lettres et la culture (FALCO), she has numerous exhibitions in the state of Quebec and abroad, and is an honorary member of the Quebec Sculpture Council.