Nel momento in cui un artista sceglie di rapportarsi in maniera diretta con la contemporaneità e tutti i suoi risvolti, tende spesso a orientarsi verso uno stile pittorico fortemente figurativo in cui poter introdurre le proprie riflessioni e considerazioni in virtù di immagini dirette, aderenti alla realtà osservata e fortemente evocative nei confronti di pensieri e sensazioni dei personaggi o dei luoghi descritti. L’artista di cui vi racconterò oggi invece, pur rimanendo nell’ambito figurativo, sceglie uno stile inusuale per dare il suo punto di vista su tutto ciò che lo circonda, a volte soffermando la sua attenzione su quanto normalmente sfugge o viene guardato solo distrattamente, altre mettendo in evidenza quelle sensazioni positive che giungono nel momento in cui ci si lascia andare alla bellezza della spontaneità e della semplicità del vivere.

Quando cominciarono a emergere le basi, i primordi di quello che era destinato a diventare uno dei maggiori movimenti artistici di ogni tempo, nessuno tra i primi teorici di quella rivoluzione cromatica e strutturale della composizione figurativa di un’opera che rispondeva al nome di Fauves poteva immaginare le modificazioni e le interpretazioni che ciascun artista aderente all’appena successiva corrente, l’Espressionismo, avrebbe apportato alle loro linee guida. Eppure nel corso degli anni successivi i colori intensi, ribelli, e lo stile di forte rottura con l’attinenza all’osservato delle regole accademiche che avevano dominato l’arte fino a quel momento, in alcuni casi si attenuarono, in altri permasero ma in qualche modo si modificò l’intento espressivo adattandolo alle sensazioni e alla personalità dell’esecutore di un’opera. Pertanto laddove Henri Matisse restò sostanzialmente legato al suo cromatismo intenso e decontestualizzato attraverso cui descrivere le scene domestiche, quel mondo familiare che per lui costituiva l’essenza della vita, Vincent Van Gogh invece utilizzò l’Espressionismo, le linee attraverso le quali stendeva il colore, come mezzo per esprimere e superare le sue angosce, la sua solitudine, l’estrema povertà che aveva contraddistinto la sua vita e infine il suo disagio mentale. E ancora, il sognatore Marc Chagall si spostò verso un universo fantastico fatto di buoni sentimenti, di spontaneità, di leggerezza, mitigando l’intensità dei colori per armonizzarli con il suo universo interiore che diventava pittura. A utilizzare invece l’Espressionismo per raccontare la realtà osservata, quel piccolo mondo quotidiano che circondava le proprie giornate, furono due grandi rappresentanti del movimento, il francese Paul Gauguin e l’italiano Renato Guttuso. Il primo lasciò alla storia dell’arte opere di grande impatto visivo ma soprattutto di descrizione di un mondo sconosciuto ai più, quello della Polinesia dove egli si era trasferito dopo diversi viaggi, per amore di una spontaneità che non apparteneva più al mondo dei salotti parigini; le sue donne intense, succinte e narrate con un tocco semplice e delicato pur mantenendo le linee guida espressioniste come la mancanza di profondità, il tratto non realista della pittura e la linea di contorno dei personaggi e degli oggetti, continuano ad affascinare aspiranti viaggiatori tanto quanto profondi estimatori dell’arte.

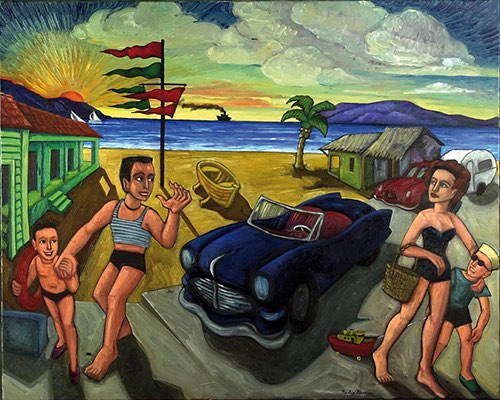

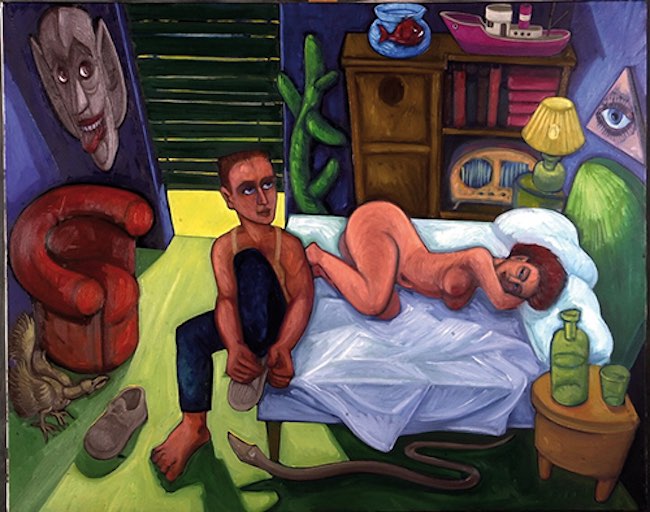

Renato Guttuso si concentrò di più sulla quotidianità, sulle persone osservate intorno a sé, sulla socialità, sugli spaccati di vita quotidiana, le scene al mercato, i balli in strada, insomma tutto ciò che colpiva la sua attenzione di uomo, e artista, attento a cosa accadesse nel mondo che viveva, diveniva protagonista delle sue opere. In qualche modo la produzione pittorica dell’artista toscano Pier Luigi Puccini subisce le influenze di questi grandi maestri del passato, immensi interpreti dell’Espressionismo che è il genere in cui si colloca il suo stile, sebbene con personalizzazioni in grado di rendere immediatamente riconoscibile una sua opera; se da un lato infatti riprende da Van Gogh la caratteristica presente in alcune tele di suddividere le pennellate in sottili linee contigue che infondono quasi un senso di profondità all’immagine finale e al tempo stesso di suggestione verso il soggetto che sceglie di descrivere in tal modo, dall’altro si ispira proprio a Guttuso per il suo osservare acutamente tutto il mondo intorno, quello di cui si fa narratore ma anche profondo indagatore di quei dettagli, di quei piccoli frangenti spesso sfuggenti ma che rivelano molto di più rispetto a quanto emergerebbe a un primo veloce sguardo.

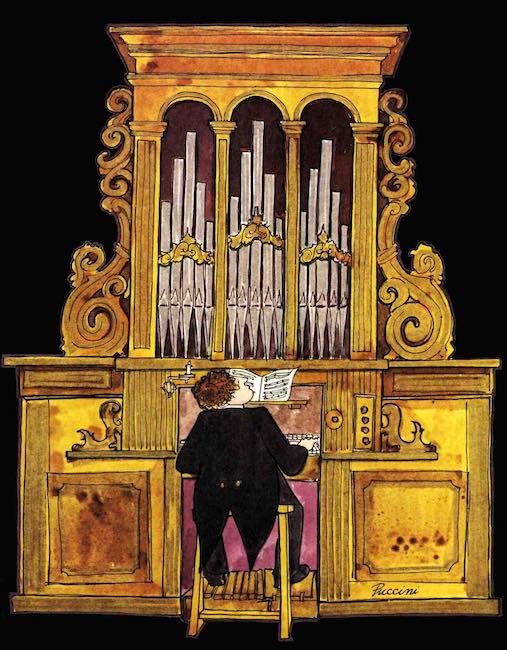

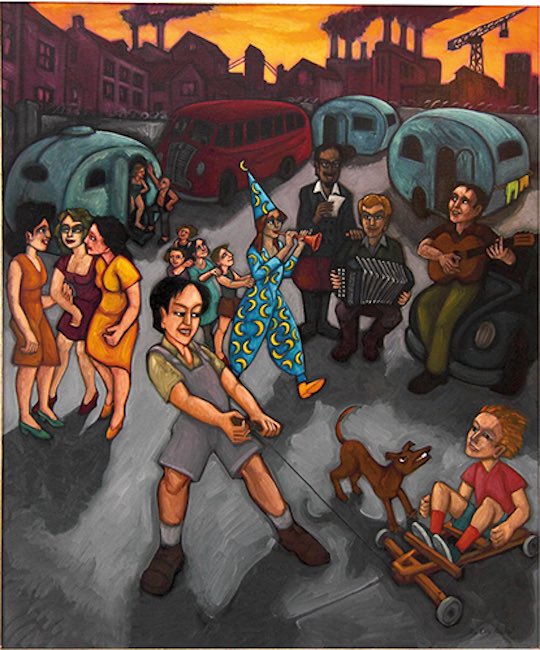

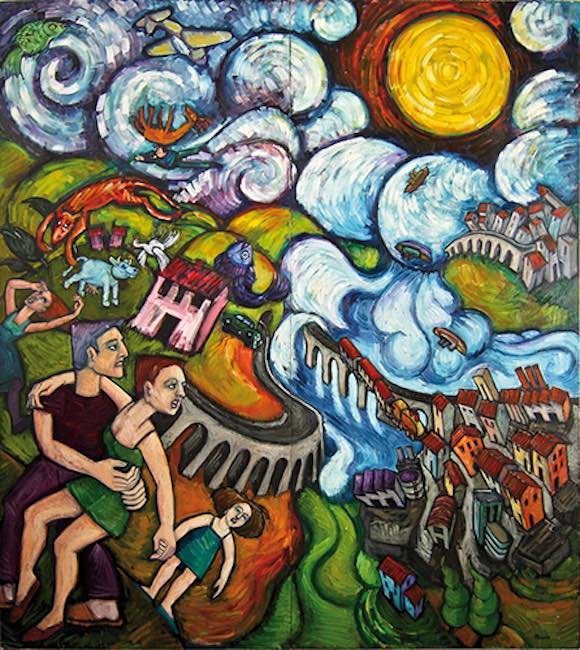

Non solo, Puccini è affascinato dalle personalità creative, forse proprio perché più libere di vivere l’esistenza secondo le proprie regole, e non quelle esterne, e dunque spesso immortala musicisti, gitani, personaggi del circo, come se appartenessero a un mondo magico, come se attraverso di loro fosse possibile mantenere il contatto con una fantasia soventemente perduta o nascosta nella realtà quotidiana.

Il suo linguaggio pittorico è fortemente espressionista, il tratto grafico con cui definisce i personaggi, gli animali e gli oggetti è molto presente, quasi a voler restare legato a un universo fanciullesco che gli permette di guardare la realtà con apertura empatica, mai giudicante piuttosto attenta e sensibile agli accadimenti che contraddistinguono la vita attuale; la scelta cromatica è intensa, vivida e vivace, in alcuni casi più piena di luce, in altri più scura ma mai cupa, tuttavia la luminosità non è mai piena o predominante, è sempre contenuta dalla forza espressiva dei colori. Ciò che però identifica più di tutto i suoi lavori è quella capacità di mettere in primo piano la spontaneità, la purezza degli atteggiamenti delle persone e dei luoghi che ritrae, quasi come se lo sguardo con cui si approccia a loro fosse quello del fanciullo incapace di vedere il negativo o di considerare un risvolto che non sia quello più candido, pur senza però perdere quel realismo con cui si pone davanti all’evidenza dell’oggettività e di tutto ciò che appartiene inevitabilmente al mondo contemporaneo.

Questo suo tocco gentile ma lucido emerge nella tela Periferia dove Pier Luigi Puccini non mette in risalto i disagi del vivere, piuttosto il desiderio dei ragazzi che vi abitano di trovare un senso, un interesse che li coinvolga di più del semplice ciondolare in strada, e ben venga che questo interesse sia costituito da uno sport; da questa opera dove il cromatismo dominante è il violetto dei palazzi, che sta a rappresentare la metamorfosi, la transizione, e dal giallo ocra del campo da calcio, come a sottolineare la concretezza da cui è necessario partire prima di inseguire il sogno. L’apparente emarginazione, rappresentata dal giovane seduto al di fuori della palizzata, è subito colmata dalla presenza dell’amorevole madre che sembra consolarlo e rassicurarlo che le cose andranno bene, dunque la speranza di una vita migliore è il vero significato di quest’opera.

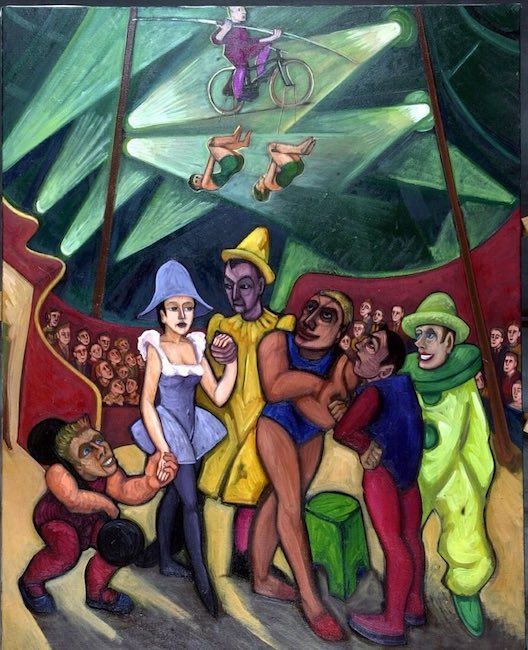

In Malinconia al contrario, Puccini parla di un sentimento poco positivo rappresentandolo con i protagonisti del circo, come se un lavoro tanto dedito a far divertire adulti e bambini, non necessariamente escludesse quel ventaglio di sentimenti che inevitabilmente appartengono all’essere umano; eppure i protagonisti della tela si stringono l’un l’altro, sono vicini, si sostengono a vicenda perché hanno capito che è solo insieme che si può uscire dalla tristezza e recuperare la positività necessaria a proseguire lo spettacolo della vita. La prospettiva è appiattita e dunque i due personaggi che guardano in alto potrebbero rivolgere la loro attenzione ai compagni funamboli oppure riflettere sui propri pensieri, preoccuparsi sulla tenuta del tendone, ogni interpretazione è lasciata all’osservatore, perché Pier Luigi Puccini non è mai interprete bensì solo novelliere, cantastorie della magia della vita.

Ed è proprio su questo accento che si sviluppa l’opera Jam session, nella piacevolezza dei musicisti nel produrre le note in grado di divertire e ammaliare il pubblico ma anche loro stessi, perché in fondo chiunque riesca a toccare le corde interiori, quelle dell’emozione, sa di essere un privilegiato; e dunque i suonatori si guardano complici per suggerirsi l’accordo armonico successivo mentre sulle loro melodie alcuni ballerini in sala si lasciano andare a un romantico ballo. In questo lavoro, malgrado abitualmente i locali di jazz siano piuttosto bui, emerge una forte luce, come se fosse proprio la malìa della musica a generare energia positiva che rompe le ombre.

Pier Luigi Puccini ha alle sue spalle un lunghissimo percorso artistico iniziato nel 1975, sempre affiancato a quello di scenografo teatrale e cinematografico, che lo ha visto protagonista di molte mostre personali a Lucca, Firenze, Venezia, Pietrasanta, Berlino, Livorno, Thiene e di diverse esposizioni collettive una delle quali in Cina nel 2008 in occasione delle Olimpiadi. Le sue opere fanno parte di collezioni private in Italia e nel mondo.

PIER LUIGI PUCCINI-CONTATTI

Email: pierluigipuccini@gmail.com

Sito web: https://pierluigipuccini.it/

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/pierluigi.puccini.5

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/pierluigipuccini/

Expressionism is transformed into a realist and sharply analytical gaze in the artworks by Pier Luigi Puccini

At a time when an artist chooses to relate directly to contemporaneity and all its implications, he often tends to lean toward a strongly figurative style of painting in which he can introduce his own reflections and considerations by virtue of direct images, adherent to the reality observed and strongly evocative in regard to the thoughts and feelings of the characters or places described. The artist I will tell you about today, on the contrary, while remaining in the figurative sphere, chooses an unusual style to give his point of view on everything that surrounds him, sometimes dwelling his attention on what normally escapes or is only looked at distractedly, others highlighting those positive sensations that come the moment one lets go to the beauty of spontaneity and simplicity of living.

When the foundations began to emerge, the beginnings of what was destined to become one of the major artistic movements of all time, no one among the early theorists of that chromatic and structural revolution in the figurative composition of an artwork that answered to the name of Fauves could have imagined the modifications and interpretations that each artist adhering to the just subsequent current, Expressionism, would make to their guidelines. Yet in the course of the following years the intense, rebellious colors, and the style of strong break with the adherence to the observed academic rules that had dominated art up to that time, in some cases subsided, in others persisted but somehow changed the expressive intent by adapting it to the feelings and personality of the author of the artwork. Therefore, where Henri Matisse remained substantially tied to his intense and decontextualized chromatism through which he described domestic scenes, that familiar world that for him constituted the essence of life, Vincent Van Gogh on the other hand used Expressionism, the lines through which he spread color, as a means of expressing and overcoming his anxieties, his loneliness, the extreme poverty that had marked his life and finally his mental distress. And again, the dreamer Marc Chagall moved toward a fantastic universe of good feelings, spontaneity, lightness, mitigating the intensity of colors to harmonize them with his inner universe that became painting. Instead, to use Expressionism to narrate the observed reality, that small everyday world that surrounded one’s days, were two great representatives of the movement, the French Paul Gauguin and the Italian Renato Guttuso. The former left to the history of art works of great visual impact but above all the description of a world unknown to most, that of Polynesia where he had moved after several trips, for the sake of a spontaneity that no longer belonged to the world of the Parisian salons; his intense, succinct women narrated with a simple and delicate touch while maintaining expressionist guidelines such as the lack of depth, the non-realist stroke of the painting and the outline of the characters and objects, continue to fascinate aspiring travelers as much as deep admirers of art.

Renato Guttuso focused more on the everyday, on the people observed around him, on sociality, on slices of daily life, scenes at the market, dancing in the streets, in short everything that struck his attention as a man, and artist, attentive to what was happening in the world he lived in, became the protagonist of his artworks. In some ways, the pictorial production of the Tuscan artist Pier Luigi Puccini is influenced by these great masters of the past, immense interpreters of Expressionism, which is the genre in which his style is placed, albeit with personalizations capable of making one of his works immediately recognizable; in fact, if on the one hand he takes from Van Gogh the characteristic present in some canvases of subdividing the brushstrokes in thin contiguous lines that almost infuse a sense of depth to the final image and at the same time of suggestion towards the subject he chooses to describe in such a way, on the other hand he is inspired precisely by Guttuso for his keen observation of the whole world around him, the world of which he becomes a narrator but also a profound investigator of those details, those small bangs that are often elusive but reveal much more than would emerge at a quick first glance. Not only that, Puccini is fascinated by creative personalities, perhaps precisely because they are freer to live existence according to their own rules, and not external ones, and therefore he often immortalizes musicians, gypsies, circus characters, as if they belonged to a magical world, as if through them it were possible to maintain contact with a fantasy often lost or hidden in everyday reality. His pictorial language is strongly expressionist, the graphic stroke with which he defines the characters, animals and objects is very present, almost as if he wanted to remain tied to a childlike universe that allows him to look at reality with empathetic openness, never judgmental rather attentive and sensitive to the happenings that mark current life; the chromatic choice is intense, vivid and lively, in some cases fuller of light, in others darker but never gloomy, however, the brightness is never full or predominant, it is always contained by the expressive force of the colors.

What, however, most identifies his artworks is that ability to foreground the spontaneity, the purity of the attitudes of the people and places he portrays, almost as if the gaze with which he approaches them were that of a child incapable of seeing the negative or of considering any implication other than the most candid, yet without losing that realism with which he stands before the evidence of objectivity and all that inevitably belongs to the contemporary world. This gentle but lucid touch of his emerges in the canvas Suburbia where Pier Luigi Puccini does not emphasize the hardships of living, rather the desire of the boys who live there to find meaning, an interest that engages them more than simply loitering in the street, and welcome that this interest consists of a sport; by this artwork where the dominant chromaticism is the violet of the buildings, which stands for metamorphosis, transition, and by the yellow ochre of the soccer field, as if to emphasize the concreteness from which it is necessary to start before pursuing the dream. The apparent marginalization, represented by the young man sitting outside the palisade, is immediately filled by the presence of his loving mother who seems to console and reassure him that things will be all right, thus the hope for a better life is the true meaning of this opera. In Melancholy on the contrary, Puccini speaks of a feeling that is not very positive by representing it with the protagonists of the circus, as if a job so dedicated to entertaining adults and children did not necessarily exclude that range of feelings that inevitably belong to human beings; yet the protagonists of the canvas hold each other, are close, and support each other because they have understood that it is only together that one can emerge from sadness and recover the positivity necessary to continue the spectacle of life.

The perspective is flattened and therefore the two characters looking up could turn their attention to their fellow tightrope walkers or reflect on their own thoughts, worry about the tightness of the tent, all interpretation is left to the observer, because Pier Luigi Puccini is never an interpreter but only a novelist, a storyteller of the magic of life. And it is precisely on this accent that the work Jam session develops, in the pleasantness of the musicians in producing the notes capable of entertaining and bewitching the audience but also themselves, because after all anyone who can touch the inner chords, those of emotion, knows that he is privileged; and so the players look at each other complicitly to suggest the next harmonic chord while over their melodies some of the dancers in the room indulge in a romantic dance. In this artwork, despite the fact that jazz clubs are usually rather dark, a strong light emerges, as if it is precisely the music’s malice that generates positive energy that breaks through the shadows. Pier Luigi Puccini has behind him a very long artistic career that began in 1975, always side by side with that of theatrical and film set designer, which has seen him as the protagonist of many solo exhibitions in Lucca, Florence, Venice, Pietrasanta, Berlin, Livorno, Thiene and several group exhibitions one of which in China in 2008 on the occasion of the Olympics. His works are part of private collections in Italy and around the world.