Il mondo naturale, l’ambiente che circonda l’uomo nel momento in cui sceglie di allontanarsi dalla routine cittadina fatta di strade e di cemento, ha costituito nel corso della storia dell’arte più recente un importante elemento rappresentativo in grado di coinvolgere non solo le sensazioni visive e percettive dell’autore dell’opera, ma anche di far vibrare le corde del fruitore che si sente coinvolto e indotto a perdersi nell’armonia o a meditare su tutto ciò che non appare e che tuttavia esiste all’interno dell’osservato. La connessione con la natura che ruota intorno alla vita dell’essere umano permette alla sensibilità di alcuni creativi di sintonizzarsi sull’ascolto della delicatezza e delle energie sottili che avvolgono il mondo e che troppo spesso rimangono inascoltate. L’artista di cui vi racconterò oggi si rende interprete delle voci più impercettibili di quel mondo che tanto ama rendere protagonista delle sue tele.

Il Diciannovesimo secolo si pose come anticipatore di tutte quelle tendenze pittoriche che si ampliarono, svilupparono e affermarono in maniera più netta e definita nel Novecento, contribuendo così a dare l’avvio alla rivoluzione artistica che poco dopo si sarebbe concretizzata con una sovversione delle regole, un distacco completo da ogni regola accademica e l’annullamento delle convenzioni che fino a poco prima avevano tenuto in piedi tutta la pittura e la scultura. Già nei primi decenni dell’Ottocento, il Romanticismo cominciò a introdurre nella tela il mondo delle sensazioni, di una percezione poetica o impetuosa che grandi maestri come Eugène Delacroix, Caspar David Friedrich, Johan Christian Dahl, Philipp Otto Runge, riuscirono a far fuoriuscire con intensità dalle loro indimenticabili opere; questa inclinazione a prestare ascolto alla soggettività dell’esecutore dell’opera, sebbene ancora mescolata con l’attenzione alla perfetta resa della realtà riprodotta, fu successivamente scalzata dal Realismo che si proponeva invece di dare una perfetta fotografia della vita dell’epoca senza che si percepisse il sentire dell’artista. Tuttavia il processo di attenzione a tutto ciò che si allontanava dall’oggettività per lasciare spazio all’ascolto di qualcosa di più intimo e intrinseco all’osservato, era stato attivato e ben presto sfociò nel Simbolismo, movimento dell’ultimo ventennio dell’Ottocento, in cui cominciò a delinearsi anche un interesse verso il soprannaturale, l’occulto, il mondo dell’aldilà, proprio per dare voce a tutto l’apparentemente inanimato che ruota intorno all’individuo e che in qualche modo sente, vive, respira, anche se in modo differente. Odilon Redon, Arnold Böcklin, Felicien Rops furono gli anticipatori di quel successivo movimento che sconvolse il Novecento con il suo mistero, l’irrequietezza dei sogni e degli incubi e che prese il nome di Surrealismo; in questo movimento la natura, malgrado la decontestualizzazione dei paesaggi e degli elementi che a essa appartengono, cominciava ad assumere significati metaforici, a trasformarsi in simbolo o ad avere una sua personalità e un suo sentire, come se fosse proiezione dei pensieri dell’autore dell’opera. Dunque laddove Salvador Dalì mostrava ambientazioni più legate al mondo degli incubi e alla sessualità, René Magritte contemplava invece la natura attribuendole significati che inducevano l’osservatore a riflettere, evocando un mondo onirico a armonioso dove tutto aveva un senso differente da quello abitualmente conosciuto.

L’artista austriaca Gabriele Simic assorbe le influenze dei movimenti sopra menzionati fondendole in uno stile poliedrico, indubbiamente figurativo, ma con cui si muove verso differenti sfaccettature e interpretazioni dell’osservato, passando dall’ammirazione poetica di paesaggi o frammenti di esistenza di piccoli animali al puro Simbolismo in cui ogni elemento si lega fortemente a un altro per infondere sulla tela l’atmosfera che l’artista desidera trasmettere. Non solo, ciò che affascina più di ogni altra cosa la Simic è la possibilità di misurarsi con molteplici tecniche e materiali, di passare dall’acquarello all’olio su tela, dall’acrilico alla tecnica mista spingendosi addirittura verso sperimentazioni più audaci normalmente utilizzate da movimenti informali, come la bruciatura di parte dell’opera che fu adottata per l’esecuzione di molti lavori da Alberto Burri, o come l’inserimento di materiali da riciclo pur senza mai abbandonare la rappresentazione della natura che è base imprescindibile delle opere di questa dinamica artista.

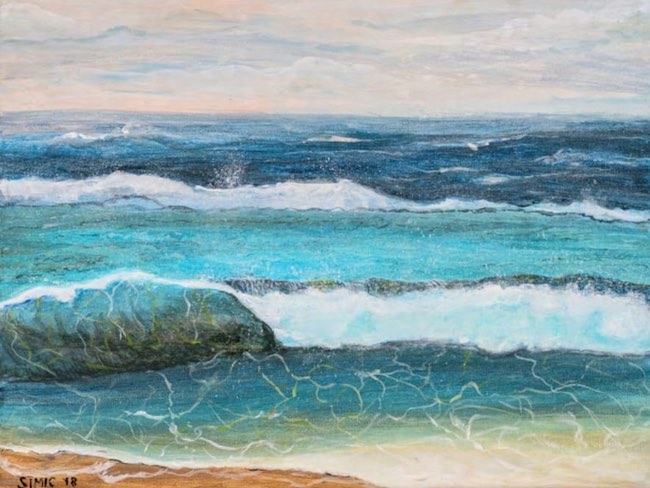

Laddove con l’acquarello il suo approccio pittorico è più delicato, morbido e orientato alla semplice osservazione di quei piccoli dettagli che la colpiscono e che compongono la realtà dentro cui il suo sguardo si perde, evidenziando brevi e irripetibili istanti che un attimo dopo sono pronti a modificarsi a causa di un soffio di vento e la cui fuggevolezza è sottolineata dalla dissolvenza dei confini, dei lati più estremi delle opere, con l’acrilico mette in evidenza il puro perdersi dentro la maestosità della realtà, cercando di riprodurne la pura bellezza che si rende evidente solo soffermandosi, sostando, di fronte al mare o agli alberi che tanto sembrano appartenere all’ordinarietà quanto invece attraverso la sensibilità di Gabriele Simic diventano straordinari.

Con l’olio su tela invece il suo approccio pittorico si sposta verso il Surrealismo Metafisico in cui l’ascolto si fa sognante e dove alla natura viene affidato il compito di essere interprete di un sentire profondo e anche voce di un grido silenzioso per risvegliare l’essere umano e metterlo in guardia dalle sue azioni nocive e irresponsabili.

L’opera Sunset with red in a drop infonde nell’osservatore una suggestione particolare perché da un lato egli è rapito dal fascino del tramonto intenso e coinvolgente ma dall’altro la sua attenzione è quasi magnetizzata dalla presenza di una goccia che sembra voler essere protagonista; la metafora è quella di un cielo che chiede solo di continuare a essere se stesso giorno dopo giorno, senza essere costretto a osservare il dolore che costantemente l’uomo infligge a se stesso e ai suoi simili, oppure il senso invece è quello della preghiera silenziosa ad avere maggiore cura di quel mondo che lo ospita e che troppo spesso viene distrutta per scopi egoistici e arrivistici.

Anche Stairs to heaven sembra in qualche modo rappresentare, seppur in modo più poetico e sognante, più orientato a mettere in luce il desiderio positivo che non il senso di disagio dell’individuo, il bisogno di astrarsi dalla realtà quotidiana, di trovare una via di fuga verso quel sogno a cui troppo spesso si rinuncia ma che permane nell’immaginazione come l’unico modo per realizzare se stessi e la propria vera essenza. La tela è un invito a trovare il coraggio di guardare in alto e compiere quel salto nel buio che malgrado il rischio condurrà a salire quei gradini verso un futuro diverso, più affine alle proprie caratteristiche; il paradiso dunque è allegoria dell’evoluzione dell’essere umano, il punto di arrivo verso un migliore se stesso che ha saputo guardarsi dentro e capire cosa davvero voleva e ha cominciato la salita verso il perseguimento del suo obiettivo interiore, senza paura di cadere bensì con la fiducia di intraprendere un meraviglioso viaggio verso sé.

La tendenza sperimentatrice di Gabriele Simic si svela in particolar modo nelle tecniche miste dove mescola ai colori acrilici anche materiali di riciclo, mostrando ancora una volta l’attenzione a quell’ambiente che tanto ama raccontare, suggerendo quanto sia importante mostrare rispetto e liberare la natura dai rifiuti che l’uomo lascia dietro di sé trasformandoli, laddove è possibile, in elementi compositivi dell’arte; nel polittico At the water lily pond la parte materica è in perfetta armonia con quella puramente coloristica, che ne costituisce la base, e mette in risalto quei lievi dettagli che infondono alla composizione dedicata ai fondali marini una maggiore aderenza alla realtà, tra luci e trasparenze delle acque.

Nella tela Phoenix Gabriele Simic si misura con le bruciature attraverso le quali evidenzia quelle ceneri dalle quali l’animale mitologico risorge e ricrea un nuovo sé; anche in questo caso non può non essere notata la forma metaforica del messaggio che fuoriesce dall’opera poiché la Fenice è da sempre simbolo di forza e di capacità di rialzarsi a dispetto delle difficoltà e dai tentativi esterni di farla soccombere, svelando così la vicinanza dell’artista anche al movimento del Simbolismo. Gabriele Simic si è formata da autodidatta e ha cominciato a dipingere in modo professionale nel 2017 e da quel momento in avanti la sua carriere artistica è decollata vedendola protagonista di molte mostre collettive e personali in Austria e all’estero, soprattutto in America Latina.

GABRIELE SIMIC-CONTATTI

Email: gabriele.simic@gmx.at

Facebook: www.facebook.com/gabriele.simic.5

The breath of nature in the artworks by Gabriele Simic, between Realism and Symbolism to listen to the subtlest sense of reality

In the course of recent art history, the natural world, the environment that surrounds man when he chooses to move away from the city routine of streets and cement, has been an important representative element capable of involving not only the visual and perceptive sensations of the author of the artwork, but also of vibrating the chords of the viewer who feels involved and induced to lose himself in the harmony or to meditate on all that does not appear and yet exists within the observed. The connection with nature that revolves around the life of the human being allows the sensitivity of some creatives to tune into listening to the delicacy and subtle energies that envelop the world and that too often go unheard. The artist I am going to tell you about today is an interpreter of the most imperceptible voices of that world that he loves so much to make the protagonist of his canvases.

The 19th century was the forerunner of all those pictorial tendencies that would expand, develop and assert themselves in a clearer and more defined manner in the 20th century, thus contributing to the start of the artistic revolution that would shortly afterwards take shape with a subversion of the rules, a complete detachment from all academic rules and the annulment of the conventions that had until recently held all painting and sculpture together. Already in the first decades of the 19th century, Romanticism began to introduce into the canvas the world of sensations, of a poetic or impetuous perception that great masters such as Eugène Delacroix, Caspar David Friedrich, Johan Christian Dahl and Philipp Otto Runge succeeded in bringing out with intensity in their unforgettable paintings; this inclination to listen to the subjectivity of the executor of the artwork, although still mixed with attention to the perfect rendering of the reproduced reality, was later undermined by Realism, which aimed instead to give a perfect snapshot of the life of the time without the artist’s feelings being perceived. However, the process of paying attention to everything that moved away from objectivity to make room for listening to something more intimate and intrinsic to the observed, had been activated and soon led to Symbolism, movement of the last two decades of the 19th century, in which an interest in the supernatural, the occult, the world of the afterlife also began to emerge, precisely in order to give voice to all the apparently inanimate that revolves around the individual and that somehow feels, lives, breathes, albeit in a different way.

Odilon Redon, Arnold Böcklin, and Felicien Rops were the forerunners of that later movement that shook the 20th century with its mystery, the restlessness of dreams and nightmares, and which took the name of Surrealism; in this movement, nature, despite the decontextualisation of landscapes and elements belonging to it, began to take on metaphorical meanings, to turn into a symbol or to have its own personality and feeling, as if it were a projection of the thoughts of the author of the artwork. So where Salvador Dali showed settings more related to the world of nightmares and sexuality, René Magritte instead contemplated nature, attributing meanings to it that induced the observer to reflect, evoking a dreamlike and harmonious world where everything had a different meaning from the usual one. The Austrian artist Gabriele Simic absorbed the influences of the above-mentioned movements and merged them into a multifaceted style, undoubtedly figurative, but with which she moves towards different facets and interpretations of the observed, moving from poetic admiration of landscapes or fragments of the existence of small animals to pure Symbolism in which each element is strongly linked to another to infuse the canvas with the atmosphere the artist wishes to convey. Not only that, but what fascinates Simic more than anything else is the possibility of measuring herself with multiple techniques and materials, of moving from watercolour to oil on canvas, from acrylic to mixed media, even going as far as more daring experiments normally used by informal movements, such as the burning of part of the artwork that was adopted for the execution of many works by Alberto Burri, or the inclusion of recycled materials without ever abandoning the representation of nature that is the essential basis of the paintings of this dynamic artist. Whereas with watercolour, her pictorial approach is more delicate, soft and oriented towards the simple observation of those small details that strike her and that make up the reality within which her gaze loses itself, highlighting brief, unrepeatable instants that a moment later are ready to change due to a gust of wind and whose fleetingness is emphasised by the fading of the most extreme sides of the works, with acrylics she emphasises the sheer loss within the majesty of reality, trying to reproduce the pure beauty that is only evident when pausing in front of the sea or trees that seem to belong to the ordinary, but through Gabriele Simic‘s sensitivity become extraordinary.

With oil on canvas, however, her pictorial approach shifts towards Metaphysical Surrealism in which listening becomes dreamy and where nature is entrusted with the task of being the interpreter of a profound feeling and also the voice of a silent cry to awaken human beings and warn them of their harmful and irresponsible actions. The painting Sunset with red in a drop infuses the observer with a particular suggestion because on the one hand he is enraptured by the charm of the intense and enthralling sunset, but on the other his attention is almost magnetised by the presence of a drop that seems to want to be the protagonist; the metaphor is that of a sky that asks only to continue to be itself day after day, without being forced to observe the pain that man constantly inflicts on himself and his fellow men, or the meaning instead is that of a silent prayer to take better care of the world that hosts him and that too often is destroyed for selfish and self-serving purposes. Stairs to heaven also seems in some way to represent, albeit in a more poetic and dreamy way, more oriented towards highlighting the positive desire than the individual’s sense of unease, the need to abstract oneself from everyday reality, to find an escape route towards that dream that is all too often renounced but which remains in the imagination as the only way to realise oneself and one’s true essence. The canvas is an invitation to find the courage to look up and take that leap in the dark that despite the risk will lead one to climb those steps towards a different future, more akin to one’s own characteristics; paradise is therefore an allegory of the evolution of the human being, the point of arrival towards a better self that has been able to look inside oneself and understand what it really wanted and has begun the climb towards the pursuit of one’s inner goal, without fear of falling but with the confidence to embark on a wonderful journey towards oneself.

Gabriele Simic‘s experimental tendency is particularly evident in her mixed media where she mixes acrylic colours with recycled materials, once again demonstrating her concern for the environment that she loves to talk about so much, suggesting how important it is to show respect and rid nature of the waste that man leaves behind, transforming it, where possible, in the compositional elements of art; in the polyptych At the water lily pond, the material part is in perfect harmony with the purely colouristic part, which forms its basis, and emphasises those subtle details that imbue the composition dedicated to the seabed with a greater adherence to reality, amidst the light and transparency of the water. In the canvas Phoenix, Gabriele Simic measures herself with the burns through which she highlights those ashes from which the mythological animal resurrects and recreates a new self; here too, the metaphorical form of the message that emerges from the artwork cannot but be noted, since the Phoenix has always been a symbol of strength and the ability to rise up in spite of difficulties and external attempts to make it succumb, thus revealing the artist’s closeness to the Symbolism. Gabriele Simic trained as a self-taught artist and began painting professionally in 2017, and from then on her artistic career took off, with her participating in many group and solo exhibitions in Austria and abroad, especially in Latin America.