La tendenza a esplorare, a conoscere tutto ciò che incuriosisce l’intelletto e l’emotività, ha da sempre esercitato una condizione essenziale all’impulso creativo di molti artisti del passato, e anche del presente, perché spesso soffermarsi solo su ciò che già si conosce non è sufficiente a costituire una fonte costante di ispirazione. E dunque il viaggio si trasforma in momento di scoperta ma anche di approfondimento delle proprie emozioni che poi si manifestano sulla tela in maniera più o meno attinente all’osservato, sulla base dell’indole del singolo autore di un’opera. L’artista di cui vi racconterò oggi è un giramondo per indole e un pittore per vocazione, così unendo le sue due passioni, racconta un mondo intenso, affine più alla sua sfera emozionale che non a ciò che lo sguardo vede, e proprio per questo molto coinvolgente.

Quando l’Impressionismo verso la fine dell’Ottocento cominciò a essere eclissato da una nuova esigenza espressiva, si delinearono movimenti innovativi che si mostrarono come superamento di quella tendenza puramente estetica e di perfezione formale che aveva contraddistinto l’arte fino a quel momento, per orientarsi verso tecniche inedite tutte volte non solo a studiare un differente utilizzo nella stesura dei colori ma anche ad assecondare l’impressione immortalata sulla tela a un sentire interiore di fronte al quale ogni equilibrio di armonia figurativa poteva scomparire per lasciare maggiore spazio a un mondo emozionale che non doveva più avere filtri. Fu esattamente in quella fase che nacquero correnti volte a osservare la realtà da punti di vista differenti e che furono preludio di successivi e più ampi movimenti destinati a segnare il corso della storia dell’arte. Il Postimpressionismo superò l’approccio pittorico libero eseguito en plein air degli impressionisti e recuperò l’importanza del disegno, il cui tratto emergeva in modo deciso e ben definito, divenendo contenitore di colori utilizzati in maniera insolita perché non più attinenti all’osservato bensì al percepito, a quel punto di vista soggettivo di cui l’esecutore dell’opera era filtro. Grandi maestri del Postimpressionismo furono Vincent Van Gogh, Paul Cézanne e Paul Gauguin, solo per citare i più celebri, e furono proprio loro a gettare le basi dell’evoluzione appena successiva che, assorbendo anche le teorie dei Fauves, prese il nome di Espressionismo. Una delle caratteristiche comune a questi tre maestri era di scomporre le immagini in linee appena accennate, tratti sottili in cui sperimentavano l’accostamento dei colori senza essere mescolati sulla tavolozza, che da un lato riproponeva la teoria degli Impressionisti, ma dall’altro la ampliava e la enfatizzava attraverso l’utilizzo di tonalità che non tendevano più a riprodurre la realtà piuttosto a stravolgerne l’impatto visivo per sollecitare il contatto con il sentire più profondo. George Seurat e Paul Signac elaborarono invece una teoria differente, o per meglio dire una suddivisione maggiore e più scientifica quasi, quella del Puntinismo per il quale la frammentazione non era più in linee bensì in piccoli punti cromatici di cui si poteva cogliere l’aspetto generale e finale solo allontanandosi dalla tela; il loro concetto era quello che, essendo ogni colore influenzato da quello accanto, essi non dovevano più essere mescolati sulla tavolozza bensì inseriti con piccoli punti sulla tela lasciando che la fusione tra essi si compisse nella retina dell’osservatore.

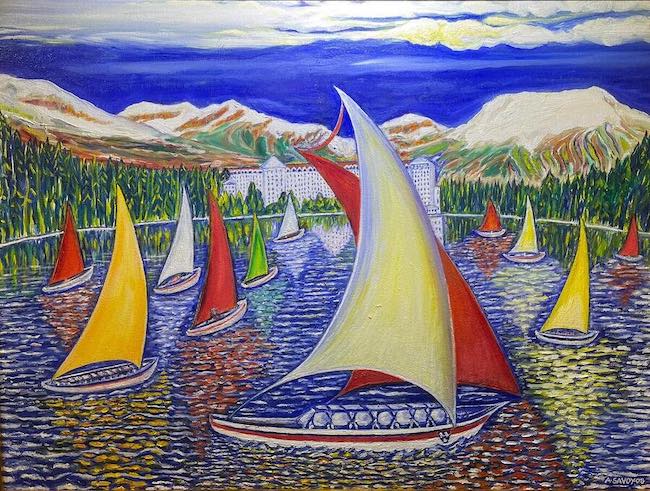

L’artista canadese ma con origini italiane Adriano Savoye appartiene al Postimpressionismo per la caratteristica di stravolgere le tonalità riscontrabili in natura adeguandole al proprio mondo interiore, ma si avvicina al Puntinismo per la tendenza in alcune tele a compiere quella suddivisione in piccoli tocchi di colore attraverso cui imprimere nell’opera le sue sensazioni più profonde e per dare all’osservatore il senso intenso di ciò che il suo sguardo ha visto nel momento in cui si è trovato davanti ai paesaggi che poi ha scelto di narrare.

Un’altra caratteristica che lo accomuna agli artisti di fine Ottocento e inizi Novecento è la sua propensione al viaggio inteso non semplicemente come modo per vedere paesi lontani, ma anche e soprattutto come mezzo per acquisire esperienze, per respirare sensazioni e per scoprire panorami differenti da quelli che abitualmente vede nel suo paese di provenienza; lo sguardo è il medesimo del sognatore, del fanciullo che osserva il mondo intorno a sé con la meraviglia della semplicità, dell’immediatezza e della spontaneità di chi non si cura dei filtri della razionalità bensì si lascia prendere all’interno di un universo a metà tra realtà e fantasia, reinterpretando tutto ciò che l’occhio vede per raccontare ciò che l’anima sente.

Ogni luogo ha lasciato in lui un segno profondo, ha scolpito nella sua memoria un simbolo indelebile poi concretizzato e personalizzato nelle sue tele costituite di colori forti, intensi tanto quanto lo erano quelli dei Fauves, descrivendo scene semplificate e proprio per questo affascinanti quanto quelle rappresentate da Van Gogh, evocando scorci di mondo, esattamente come Gauguin o Emil Nolde, contraddistinti da tonalità irreali quanto però in armonia con le emozioni percepite. Ciò che rende inconfondibili le opere di Adriano Savoye è tuttavia quella tendenza al Puntinismo o comunque alla scomposizione delle immagini che a volte si estende all’intera tela mentre in altri casi viene limitato a una parte di essa, come se determinati dettagli avessero bisogno di essere più enfatizzati e analizzati dal punto di vista cromatico rispetto agli altri.

In Primavera nei paesi dei tulipani infatti nella parte superiore del dipinto, quella piena e intensa appartenente al cielo e al grande disco arancio del sole al tramonto, il colore è steso in maniera uniforme, tradizionale, mescolato sulla tavolozza per ottenere l’effetto cromatico desiderato da Savoye, mentre la parte inferiore, quella dei campi di fiori tipici dell’Olanda, paese a cui fa riferimento il dipinto, sono puntinati, suddivisi in piccoli tocchi con i quali l’artista definisce la tonalità naturale mescolandola a quella del riflesso del sole, infondendo a quei puntini tonali l’effetto della suddivisione che tanto lo contraddistingue e che sembra emergere in modo persino più chiaro allontanandosi dalla tela. L’emozione che ne fuoriesce è di fascinazione totale, la rigorosità quasi geometrica della composizione sottolinea quanto lo sguardo di Savoye si sia perso dentro la regolarità di un panorama rilassante e al tempo stesso esaltante, enfatizzato proprio dalle tonalità scelte per narrarlo.

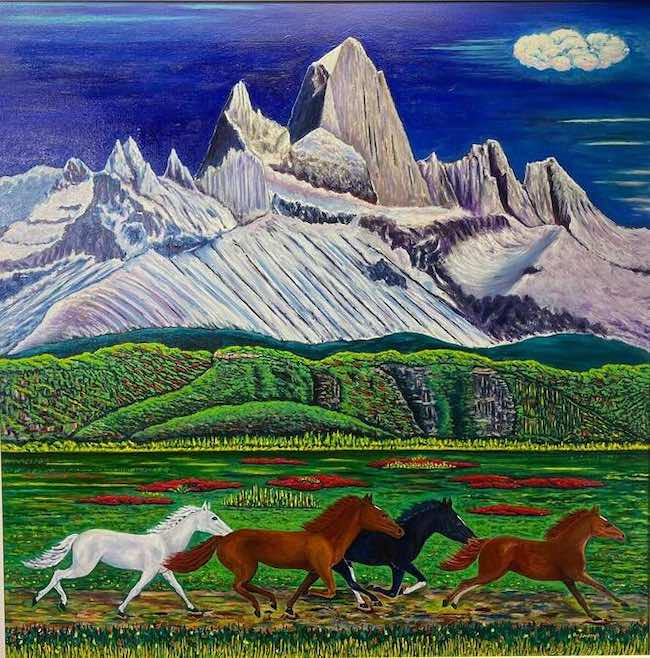

Nell’opera Patagonia meravigliosa sceglie invece un approccio differente, quello delle linee, brevi e sottili, attraverso le quali descrive un panorama mozzafiato, selvaggio e incontaminato in cui le montagne sembrano voler vegliare sulla prateria sottostante, giganti protettivi di un mondo che dovrebbe restare per sempre così, lontano da un’urbanizzazione che tenderebbe a snaturarlo. Le linee con cui Savoye racconta le montagne sembrano evidenziare la loro durezza ghiacciata, una corazza difensiva con cui nascondono il mondo di sotto, quei prati verdi puntinati di fiori su cui corrono liberi i cavalli e che sembrano a essere destinati a rimanere quell’angolo di paradiso naturale del momento in cui l’artista ha visitato uno degli angoli più remoti e impervi del globo terrestre.

In Campanile dietro la collina emerge l’anima più espressionista di Adriano Savoye, quella completa e totale decontestualizzazione cromatica appartenente ai più radicali esponenti del movimento del primo ventennio del Novecento e che sembra rivivere in questo originale e intenso artista canadese; non solo, anche lo spessore dei contorni di ogni elemento che fa parte del dipinto sottolinea il forte legame con l’Espressionismo tedesco, quello di Karl Schmidt-Rottluff e di Ernest Ludwig Kirchner, e che viene ridisegnato e reinterpretato con l’abituale sguardo fanciullesco che contraddistingue Savoye. In questa tela emergono infatti dettagli giocosi, conigli saltellanti, fili d’erba a grandezza innaturale, quasi come se l’artista si fosse immerso in un paesaggio uscito da Alice nel paese delle meraviglie, di cui osservare ogni particolare con la visionarietà di un bambino, trasformando tutto in gioco visivo con cui conquistare l’osservatore.

Un universo tutto da scoprire quello di Adriano Savoye che sa parlare all’interiorità tralasciando tutti quei filtri razionali che contribuirebbero solo a distogliere dal legame con il sentire che permette all’osservatore di abbassare le difese aprendosi a possibilità diverse e a un modo di vivere più spontaneo e immediato. Adriano Savoye partecipa costantemente a mostre collettive in ciascun paese nel quale il suo spirito girovago lo porta e lo induce a fermarsi, le sue opere fanno parte di collezioni private in tutto il mondo.

ADRIANO SAVOYE-CONTATTI

Email: iotipresento@gmail.com

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/marcella.curcio.35

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/curciomarcella/

The Post-Impressionist landscapes of Adriano Savoye, telling in his own way the world he discovered during his many travels

The tendency to explore, to know everything that intrigues the intellect and the emotions, has always been an essential condition for the creative impulse of many artists of the past, and also of the present, because often dwelling only on what one already knows is not enough to constitute a constant source of inspiration. And so the journey becomes a moment of discovery, but also of deepening one’s emotions, which then manifest themselves on the canvas in a manner more or less relevant to the observed, based on the temperament of the individual author of an artwork. The artist I am going to tell you about today is a globetrotter by nature and a painter by vocation, so by combining his two passions, he recounts an intense world, more akin to his emotional sphere than to what the eye sees, and for this very reason very engaging.

When, towards the end of the 19th century, Impressionism began to be eclipsed by a new expressive need, emerged innovative movements that showed to be an overcoming of the purely aesthetic tendency and formal perfection that had characterised art up to that time, in order to move towards new techniques all aimed not only at studying a different use of colour but also to indulge the impression immortalised on canvas to an inner feeling in front of which every balance of figurative harmony could disappear to leave more space to an emotional world that no longer must have any filters. It was precisely in that phase that were born currents that aimed to observe reality from different points of view and that were preludes to subsequent and broader movements destined to mark the course of art history. Post-Impressionism went beyond the free pictorial approach executed en plein air of the Impressionists and recovered the importance of drawing, whose stroke emerged in a decisive and well-defined manner, becoming a container of colours used in an unusual way because they no longer related to the observed but to the perceived, to that subjective point of view of which the executor of the artwork was a filter. The great masters of Post-Impressionism were Vincent Van Gogh, Paul Cézanne and Paul Gauguin, to name but the most famous, and it was they who laid the foundations for the just subsequent evolution that, also absorbing the theories of the Fauves, took the name of Expressionism. One of the characteristics common to these three masters was to break up images into barely sketched lines, thin strokes in which they experimented with the juxtaposition of colours without mixing them on the palette, which on the one hand re-proposed the theory of the Impressionists, but on the other expanded and emphasised it through the use of tones that no longer tended to reproduce reality but rather to distort its visual impact in order to solicit contact with the deepest feeling.

On the other hand, George Seurat and Paul Signac elaborated a different theory, or rather a greater and more scientific subdivision almost, that of Pointillism for which the fragmentation was no longer in lines but in small chromatic dots whose general and final appearance could only be grasped by moving away from the canvas; their concept was that, each colour being influenced by the one next to it, they should no longer be mixed on the palette but rather inserted with small dots on the canvas, letting the fusion between them take place in the observer’s retina. The Canadian artist, but with Italian origins, Adriano Savoye belongs to Post-Impressionism for the characteristic of distorting the tones found in nature by adapting them to his own inner world, but he is closer to Pointillism for the tendency in some canvases to make that subdivision into small touches of colour through which he imprinted his deepest feelings in the artwork and to give the observer the intense sense of what his gaze saw when he found himself in front of the landscapes he then chose to narrate. Another characteristic that unites him with the artists of the late 19th and early 20th century is his propensity to travel, intended not simply as a way of seeing distant countries, but also and above all as a means of gaining experience, breathing in sensations and discovering panoramas different from those he usually saw in his home country; his gaze is the same as that of the dreamer, of the child who observes the world around him with the wonder of simplicity, immediacy and spontaneity of one who does not care about the filters of rationality but allows himself to be taken inside a universe somewhere between reality and fantasy, reinterpreting everything the eye sees to tell what the soul feels. Every place has left a profound mark on him, has carved an indelible symbol in his memory, then concretised and personalised in his canvases made up of strong colours, just as intense as those of the Fauves, describing simplified scenes that are just as fascinating for this reason as those represented by Van Gogh, evoking glimpses of the world, just like Gauguin or Emil Nolde, marked by unreal tones that are, however, in harmony with the emotions perceived. What makes Adriano Savoye’s works unmistakable, however, is that tendency towards Pointillism or in any case to the decomposition of the images that sometimes extends to the entire canvas while others is limited to a part of it, as if certain details needed to be more emphasised and analysed chromatically than others. In Spring in the Tulip Country, in fact, in the upper part of the painting, the full and intense part belonging to the sky and the great orange disc of the setting sun, the colour is spread evenly, traditionally, mixed on the palette to achieve the chromatic effect desired by Savoye, while the lower part, that of the fields of flowers typical of the Holland, the country to which the painting refers, are dotted, subdivided into small touches with which the artist defines the natural hue by mixing it with that of the sun’s reflection, infusing those tonal dots with the effect of subdivision that so distinguishes him and that seems to emerge even more clearly as one moves away from the canvas.

The emotion that emerges is one of total fascination, the almost geometric rigour of the composition emphasising how much Savoye‘s gaze was lost in the regularity of a relaxing yet exhilarating landscape, emphasised precisely by the tones chosen to narrate it. In the artwork Patagonia marvellous, however, he chooses a different approach, that of the lines, short and thin, through which he describes a breathtaking, wild and uncontaminated landscape in which the mountains seem to want to watch over the prairie below, protective giants of a world that should remain like this forever, far from an urbanisation that would tend to distort it. The lines with which Savoye depicts the mountains seem to emphasise their icy hardness, a defensive armour with which they conceal the world below, those green meadows dotted with flowers on which the horses run free and which seem destined to remain that corner of natural paradise when the artist visited one of the most remote and inaccessible corners of the globe. In Bell tower behind the hill emerges the most expressionist soul of Adriano Savoye, that complete and total chromatic decontextualisation belonging to the most radical exponents of the movement of the first two decades of the 20th century and that seems to revive in this original and intense Canadian artist; not only that, even the thickness of the contours of each element in the painting emphasises the strong link with German Expressionism, that of Karl Schmidt-Rottluff and Ernest Ludwig Kirchner, and which is redrawn and reinterpreted with the usual childlike gaze that distinguishes Savoye.

In this canvas, playful details emerge, hopping rabbits, blades of grass of unnatural size, almost as if the artist had immersed himself in a landscape straight out of Alice in Wonderland, of which he observes every detail with the visionariness of a child, transforming everything into a visual game with which to captivate the observer. Adriano Savoye‘s is a universe waiting to be discovered, that knows how to speak to the inner self, leaving aside all those rational filters that would only contribute to distracting from the link with feeling that allows the observer to lower his defences, opening up to different possibilities and to a more spontaneous and immediate way of living. Adriano Savoye constantly participates in group exhibitions in each country where his wandering spirit takes him and induces him to stop, and his artworks are part of private collections all over the world.