L’osservazione della realtà circostante, di tutto ciò che ruota intorno all’essere umano nella complessità del vivere attuale, è per molti creativi apparentemente secondaria rispetto a tutto quel sottobosco emozionale che necessita un’esplorazione più intimista, intensa e attenta proprio per le difficoltà che l’uomo contemporaneo incontra nell’esprimere se stesso, nel rapportarsi con quella profondità che spesso tende a escludere perché troppo impegnativa. Esistono però alcuni artisti per i quali è impossibile prescindere da quel panorama, più o meno dettagliato e fedele alla realtà, che costituisce il mondo abitato, un fitto groviglio di palazzi, di vie, di città all’interno di cui la vita si dipana, giorno dopo giorno, senza poter prescindere da un ambiente che in qualche modo riflette e amplifica il sentire del singolo o, al contrario, è l’emozione del soggetto a estendersi fino al circostante. La protagonista di oggi appartiene a questo sensibile gruppo di artisti.

A partire dai primi anni del Novecento, l’indefinitezza e la frammentazione dell’immagine furono essenziali per effettuare non solo la ricerca avanguardista sul movimento e su un inedito modo di narrare l’osservato, ma anche per compiere uno studio sul colore che poteva essere completamente distaccato, non aderente alla realtà, purché fosse affine al sentire interiore, in accordo con le corde emotive oppure mentali dell’esecutore dell’opera d’arte. Soprattutto ciò che cominciò a divenire importante al punto spesso di prevalere, fu l’attenzione all’ambiente circostante, non più dunque solo al protagonista umano bensì anche al contatto con la natura e con le vivaci vite cittadine di quell’epoca, confermando e amplificando di fatto una delle linee guida dei movimenti appena precedenti, l’Impressionismo e il Divisionismo, in cui gli artisti scoprirono il piacere di dipingere all’aria aperta, lasciandosi trasportare dalla bellezza del paesaggio che si trovavano davanti agli occhi. Alla staticità placida e all’orientamento fortemente estetico di quelle prime rivoluzioni espressive seguirono però nuovi e inediti modi di intendere la pittura, in cui la perfezione della forma era secondaria rispetto all’idea di movimento e di rapido progresso, come nel caso del Futurismo, o alla necessità di scomporre completamente l’immagine per infondere nell’osservatore un senso di disorientamento ma anche un interrogativo su cosa si nascondesse dietro l’apparenza, come nella linea guida Cubista. Poi l’indefinito divenne imperativo e così l’Astrattismo si distaccò completamente da ciò che lo sguardo vedeva per entrare nel mondo del significato, del concetto, dell’immaginario; tuttavia vi furono maestri, come Paul Klee, che non vollero mai completamente effettuare quel distacco perché la riflessione, l’interiorizzazione, poteva convivere con una lieve figurazione geometrica proprio per aiutare e indurre il fruitore dell’opera ad avere punti di riferimento da cui partire. Nel suo caso dunque non solo il paesaggio assumeva un senso ben definito all’interno della tela, ma fungeva anche da sottofondo per l’ascolto più intenso di quelle forti emozioni che necessitavano essere contestualizzate, associate a un intorno determinante proprio perché a volte lo stesso che determinava quel fluire di sensazioni. La scomposizione dell’immagine, la sua trasparenza, il desiderio di non riprodurla nel dettaglio appartiene anche a una nuova corrente artistica, l’Impressionismo contemporaneo, in cui l’approccio pittorico è simile a quello del movimento originario di fine Ottocento, tuttavia in qualche modo si distacca dalla pura immagine, dalla sola estetica, per entrare nel mondo del percepito, dell’ascoltato, dell’atmosfera che dagli ambienti si genera.

L’artista di origini abruzzesi Luisa Muzi, residente a Roma ormai da anni, associa il fascino del paesaggio, a volte urbano altre più naturale, sovrapponendolo a quell’indefinito che contraddistingue le sue tele ma anche in fondo il suo animo sensibile che le permette di porsi in ascolto delle energie sottili che avvolgono i luoghi così come l’esistenza dell’essere umano di oggi. Le tonalità utilizzate sono a volte tenui e sfumate, altre più decise e vivaci, e poi vi sono quelle più intense e fumose, in base all’emozione, alla narrazione che l’artista si appresta a immortalare nell’opera; lo strumento attraverso il quale riesce invece a esprimersi con maggiore agevolezza è la spatola che le permette di definire e scolpire graficamente gli elementi che desidera fuoriescano dall’imprecisione dello sfondo, necessari per rilasciare l’atmosfera appartenente al frangente immortalato.

Nell’opera Passaggi la Muzi racconta di un luogo in cui il suo sguardo si è perso, tra palazzi ed elementi naturali semplici come il sole e il cielo che non appare azzurro come ci si aspetterebbe bensì si tinge di giallo per sottolineare quanto il piacere di quella giornata abbia suscitato in lei la positività e la gioia sorridente che le hanno permesso di fotografare con l’emotività per poi liberare attraverso il ricordo tutto il sentire interiore appartenente a quel preciso istante. Le sfumature delicate, i toni del rosa che prevalgono sulla tela, contribuiscono a infondere un senso di levità, di serenità all’osservatore il quale si sente avvolto e coinvolto in quel luogo dell’anima.

In Percorsi, al contrario, lo sfondo è più polveroso, più scuro perché l’opera sottintende un cammino a volte lungo che è metafora della ricerca di se stessi, una ricerca che può essere compiuta in virtù del contatto con la religione, come suggerito dalla presenza di un crocifisso a sovrastare il paesaggio sottostante, oppure attraverso un’approfondita esplorazione delle proprie profondità, delle proprie forze e debolezze, tutto ciò che possa condurre verso un’evoluzione. Il mondo sottostante è fermo, immobile, come se fosse in attesa del successivo gradino, della quiete dopo la tempesta di scoperta, o forse rappresenta semplicemente chi quel cammino lo ha terminato e non può che restare in osservazione e ascolto di quello degli altri. La contrapposizione tra la saggezza e la sete di conoscenza è ciò che emerge da questa tela, un mondo sospeso nella parte superiore, costituito da sacralità e solennità, e uno statico ma meno intenso nella parte inferiore, in cui continua a scorrere la quotidianità senza quasi che chi vi si trova dentro se ne dia conto.

Nell’opera Coronamondo, dedicata agli ultimi due anni della storia contemporanea, quella che si sta scrivendo davanti ai nostri occhi, Luisa Muzi passa in maniera più incisiva all’Astrattismo perché le sensazioni vissute sono inspiegabili, irrazionalmente devastanti per l’interiorità dell’intera umanità che si è trovata dalla sera alla mattina a non avere più alcuna certezza, a dover rinunciare al contatto con le persone vicine, quelle che fino al giorno prima facevano parte della loro vita e che, da quel punto in poi sono diventate assenti pur non volendolo, voci che uscivano dal cellulare senza più un abbraccio, senza più un sorriso. L’atmosfera è cupa, scura, proprio come buia è ancora oggi quella fase in cui le persone si guardano l’un l’altra con sospetto, con diffidenza, con il timore di perdere la vita al punto di dimenticarsi di viverla; ecco, è proprio questo il messaggio della Muzi, con la parte superiore del quadro realizzata in tonalità chiare e luminose sembra suggerire che esiste la possibilità di uscire dal tunnel e di rigenerarsi, di ritrovare la luce che porterà di nuovo l’umanità verso l’alto, verso il cielo perché non è possibile restare a lungo nell’abisso.

Ma l’artista ha un irriducibile approccio positivo, solare, aperto, ed è la base della sua espressione creativa che non può fare a meno di emergere, come nella tela Alchimia, in cui le tonalità degli azzurri, abitualmente considerati colori freddi, hanno invece la capacità di scaldare e ammorbidire, di circondare di magia l’intera tela da cui trapelano le vibrazioni positive e intense del momento in cui si lascia andare in maniera libera alle sensazioni che prova.

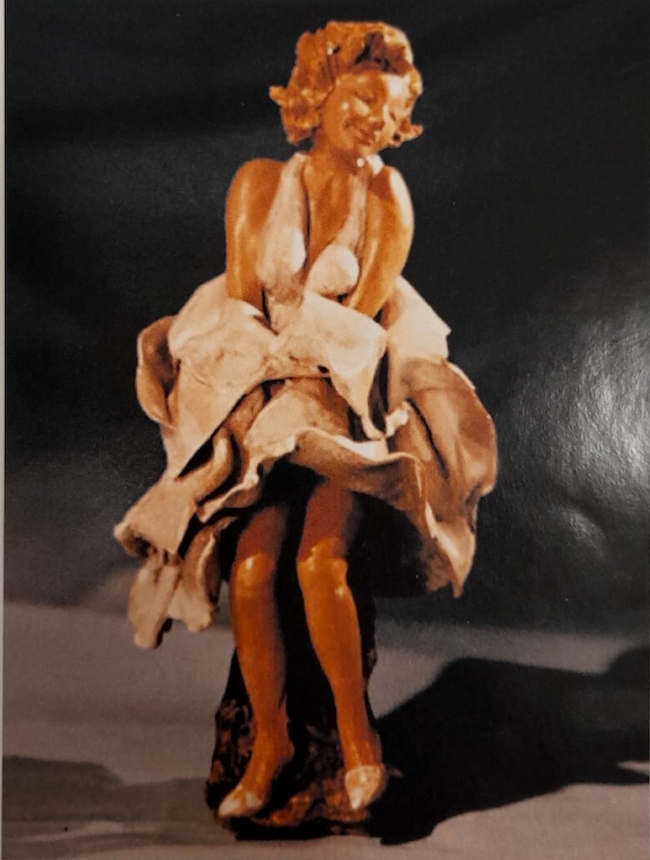

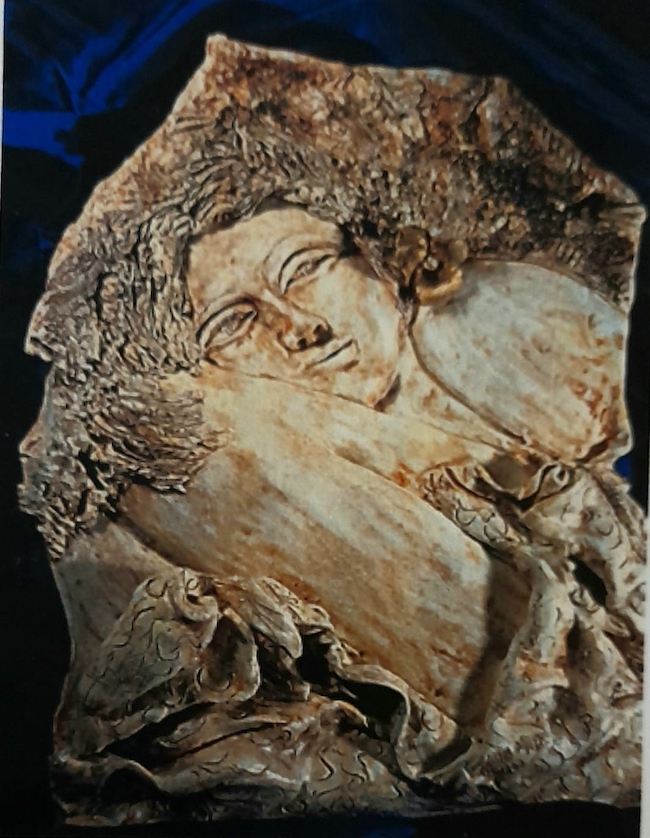

Non solo pittrice ma anche scultrice e ceramista, Luisa Muzi ha avviato una recente produzione di bassorilievi in argilla cotta a due fuochi in cui rappresenta volti che esprimono a loro volta, la sua delicata predisposizione all’ascolto emozionale, al tradurre in figurazione tutto ciò che a parole non può essere spiegato affidandolo alla sua forte indole espressiva; l’opera Sogno appartiene a questa produzione.

Luisa Muzi nel corso della sua lunga carriera ha partecipato a numerose mostre collettive, è stata selezionata per partecipare alla Biennale di Roma organizzata dal CIAC-Centro Internazionale Artisti Contemporanei nel 2018 e nel 2020 ed è membro dell’Associazione Cento Pittori di via Margutta.

LUISA MUZI-CONTATTI

Email: luisa.muzi@gmail.com

Sito web: www.luisamuzi.it

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/luisamuziartist

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/luisamuzi/

Luisa Muzi’s hidden landscapes, between sensations and indefiniteness revealed through colour

The observation of the surrounding reality, of everything that revolves around the human being in the complexity of modern life, is for many creatives apparently secondary compared to all that emotional undergrowth that requires a more intimate, intense and careful exploration precisely because of the difficulties that contemporary man encounters in expressing himself, in relating to that depth that he often tends to exclude because it is too demanding. There are, however, some artists for whom it is impossible to disregard that panorama, more or less detailed and faithful to reality, which constitutes the inhabited world, a dense tangle of buildings, streets and cities within which life unfolds, day after day, without being able to disregard an environment that somehow reflects and amplifies the feeling of the individual or, on the contrary, it is the subject’s emotion that extends to the surrounding area. Today’s protagonist belongs to this sensitive group of artists.

From the early years of the twentieth century, the indefiniteness and fragmentation of the image were essential not only to perform an avant-garde research into movement and an unprecedented way of narrating the observed, but also to carry out study into colour that could be completely detached, not adhering to reality, as long as it was akin to the inner feeling, in tune with the emotional or mental chords of the executor of the artwork. Above all, what began to become important to the point of often prevailing was the focus on the surrounding environment, no longer only on the human protagonist but also on contact with nature and the lively city life of the time, confirming and amplifying in fact one of the guidelines of the movements that had just preceded it, Impressionism and Divisionism, in which artists discovered the pleasure of painting on open air, letting themselves be carried away by the beauty of the landscape before their eyes. However, the placid static nature and highly aesthetic orientation of those early expressive revolutions was followed by new and unprecedented ways of understanding painting, in which the perfection of form was secondary to the idea of movement and rapid progress, as in the case of Futurism, or the need to completely break up the image in order to instil in the viewer a sense of disorientation but also a questioning of what lay behind the appearance, as in the Cubist guideline.

Then the indefinite became imperative and so Abstractionism detached itself completely from what the eye could see in order to enter the world of meaning, of the concept, of the imaginary. However, there were masters, such as Paul Klee, who never wanted to make that detachment completely because reflection, interiorisation, could coexist with a slight geometric figuration precisely to help and induce the viewer to have points of reference from which to start. In his case, therefore, not only did the landscape take on a well-defined sense within the canvas, but it also acted as a background for the more intense listening of those strong emotions that needed to be contextualised, associated with a decisive surrounding area precisely because at times it was the same one that determined that flow of sensations. The decomposition of the image, its transparency, the desire not to reproduce it in detail also belongs to a new artistic movement, Contemporary Impressionism, in which the pictorial approach is similar to that of the original movement at the end of the 19th century, yet somehow moves away from the pure image, from aesthetics alone, to enter the world of the perceived, of the heard, of the atmosphere generated by the environments. The artist, originally from Abruzzo, Luisa Muzi, who has lived in Rome for many years, associates the charm of the landscape, sometimes urban and sometimes more natural, overlapping it with the indefinite that distinguishes her canvases, but also her sensitive soul that allows her to listen to the subtle energies that surround places as well as the existence of today’s human beings. The tones she uses are at times soft and muted, at others stronger and more vibrant, and then there are the more intense and smoky ones, depending on the emotion, the narrative that the artist is preparing to immortalise in the artwork; the instrument with which she is able to express herself with greater ease is the spatula, which allows her to define and graphically sculpt the elements that she wishes to emerge from the imprecision of the background, necessary to release the atmosphere belonging to the situation immortalised.

In her painting Passaggi (Passages), Muzi tells of a place where her gaze is lost, among buildings and simple natural elements such as the sun and the sky, which does not appear as blue as one would expect but is tinged with yellow to underline how the pleasure of that day has aroused in her the positivity and smiling joy that have enabled her to photograph emotionally and then release through memory all the inner feeling belonging to that precise instant. The delicate shades, the tones of pink that prevail on the canvas, help to instil a sense of lightness, of serenity in the observer who feels enveloped and involved in that place of the soul. In Percorsi (Paths), on the other hand, the background is dustier, darker, because the artwork implies a sometimes long journey that is a metaphor for the search for oneself, a search that can be carried out by virtue of contact with religion, as suggested by the presence of a crucifix towering over the landscape below, or through an in-depth exploration of one’s own depths, one’s own strengths and weaknesses, anything that can lead towards an evolution. The world below is still, motionless, as if waiting for the next step, the calm after the storm of discovery, or perhaps it simply represents those who have completed that journey and can only remain in observation and listening to that of others. The contrast between wisdom and the thirst for knowledge is what emerges from this canvas, a world suspended in the upper part, made up of sacredness and solemnity, and a static but less intense one in the lower part, in which everyday life continues to flow without those inside almost noticing. In the canvas Coronamondo (Coronaworld), dedicated to the last two years of contemporary history, the one that is being written in front of our eyes, Luisa Muzi switches more incisively to Abstractionism because the sensations experienced are inexplicable, irrationally devastating for the interiority of the whole of humanity, which has found itself from night to morning no longer having any certainty, having to give up contact with people close to them, those who had been part of their lives until the day before and who, from that point onwards, became absent even though they did not want to be, voices coming out of their mobile phones without a hug, without a smile.

The atmosphere is gloomy, dark, just as dark as that phase in which people still look at each other with suspicion, with mistrust, with the fear of losing their lives to the point of forgetting to live them; this is precisely Muzi’s message, with the upper part of the painting painted in light, luminous tones, suggesting that there is a possibility of emerging from the tunnel and regenerating, of finding the light that will take humanity upwards again, towards the sky, because it is not possible to remain in the abyss for long time. But the artist has an irreducibly positive, sunny, open approach, and this is the basis of her creative expression that cannot fail to emerge, as in the painting Alchimia (Alchemy), in which the shades of blue, usually considered cold colours, have the capacity to warm and soften, to surround the entire canvas with magic, from which the positive, intense vibrations of the moment in which she lets herself go freely to the sensations she feels, seep out. Not only a painter but also a sculptor and ceramist, Luisa Muzi has recently started a production of bas-reliefs in clay fired in two fires in which she represents faces that express in turn, her delicate predisposition to emotional listening, to translate into figuration all that cannot be explained in words entrusting it to her strong expressive nature; the work Sogno (Dream) belongs to this production. Luisa Muzi during her long career has participated in numerous group exhibitions, she has been selected to participate in the Rome Biennale organized by CIAC-Centro Internazionale Artisti Contemporanei in 2018 and 2020 and she is a member of the Associazione Cento Pittori di via Margutta.