L’automatismo di rigenerazione che contraddistingue la natura ha costituito sempre una sorta di emblema, di spinta propulsiva per l’uomo a cercare il medesimo approccio anche per se stesso; l’arte non si è sottratta al fascino dello studio della nascita, dell’impulso di partenza da cui tutto ha vita e che ha identificato e iconizzato nella forma dell’uovo, raccontata e riprodotta con i diversi stili che si sono avvicendati nel corso dei secoli e che a tutt’oggi costituiscono uno spunto di costante ricerca e ispirazione per gli autori contemporanei. Il protagonista di oggi parte proprio dalla forma ovoidale per esplorare il mondo attuale e riflettere sull’esistenza dell’uomo e delle cose intorno.

L’attrattiva esercitata dall’uovo sull’essere umano e sugli artisti ha radici primordiali, perché si è sempre imposto come inizio della generazione da una corazza apparentemente fragile e liquida fino a dare corpo a una vita associandosi pertanto all’esigenza dell’uomo di invocare e di anelare la capacità di tendere verso la purezza, verso la perfezione che trova il suo spazio in quella forma ovoidale, protettiva ma al tempo stesso pronta a dischiudersi per lasciar fluire una nuova esistenza. Già intorno al Quattrocento Hieronymus Bosch, il primo simbolista anticipatore del Surrealismo per le sue immagini inquietanti e al tempo stesso magnetiche per la loro improbabilità, per la loro irrealtà, usò l’uovo in molti dipinti narrandolo come desiderio del ritorno a una dimensione di pace, un nuovo tuffo verso quella protezione ancestrale che nella società dell’epoca, ricca di insidie, non era possibile trovare. Malgrado nel corso degli anni molti grandi artisti come Velazques e Bruegel, con la loro pittura di genere, raccontarono immagini di vita quotidiana in cui in qualche modo le uova ne furono co-protagoniste, e a fine Ottocento Fabergé avesse deciso di creare le sue sfarzose e preziose Uova in onore degli zar di Russia, accentuandone dunque la valenza estetica, la pura bellezza della forma che poteva essere arricchita di dettagli e di lavorazioni che la rendessero ancor più affascinante, fu necessario attendere gli inizi del Ventesimo secolo per ritrovare quel significato simbolico della forma ovoidale di cui Bosch fu precursore. Il Surrealismo infatti esplorò da diversi punti di vista il senso più profondo dell’uovo, meditativo e ironico in René Magritte, più esplicito e legato alla carnalità, alla rigenerazione e al ritrovamento di una purezza dimenticata in Salvador Dalì. Ma anche Giorgio De Chirico nella sua Metafisica non poté fare a meno di introdurlo, decontestualizzandolo, come elemento di una realtà senza tempo, tanto quanto Fontana nello Spazialismo ne affrontò sia il riferimento alla fertilità, sia il nichilismo, il principio del nulla, in particolar modo nella sua serie di tele in cui lo raffigurava pieno di buchi, di aperture. Anche la fotografia con un altro grande esponente del Surrealismo contemporaneo, Chema Madoz, ha affrontato il tema dell’uovo come simbolo esplorativo della realtà, come rifugio ma anche come elemento che può mettere in dubbio le certezze. Lo scultore e disegnatore torinese Franco Nicolosi rende la forma ovoidale protagonista quasi assoluta delle sue sculture di forte richiamo metafisico, anche se in alcuni casi tendono verso l’Astrattismo, così come dei suoi disegni in cui affronta il rapporto tra vuoto e pieno, esaltandone il simbolismo e tutto ciò che la mente è stimolata a esplorare in virtù del mistero dei suoi emisferi che tutto contengono ma che in realtà lasciano anche fuoriuscire, come se il senso di protezione fosse effimero o come se a seguito del momento della nascita sia necessario propagare verso l’esterno l’energia vitale, il frutto di quella generazione affinché si ponga in relazione con la vita.

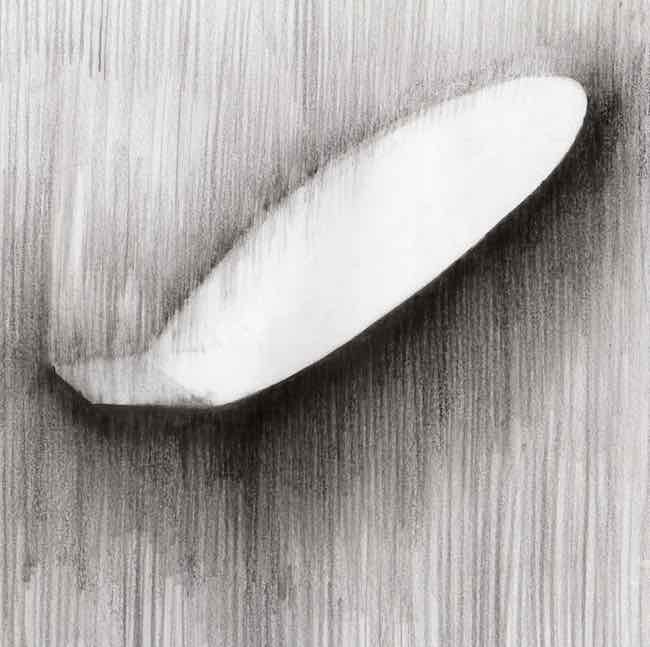

Argilla bianca, terracotta, resina epossidica e acciaio sono alcuni tra i materiali preferiti per dare vita alle sue sculture, levigandone e dipingendone le superfici per adattarsi all’intento creativo e comunicativo, lasciando che le opere siano un mezzo di divulgazione del pensiero, del senso del tutto, dell’approccio riflessivo e meditativo che contraddistingue la filosofia espressiva di Nicolosi, docente di Arte e Scenografie Teatrali e Cinematografiche e per questo fortemente orientato alla sperimentazione, alla necessità di esplorare nuove tecniche, nuovi linguaggi che possano essere funzionali a manifestare la propria interiorità.

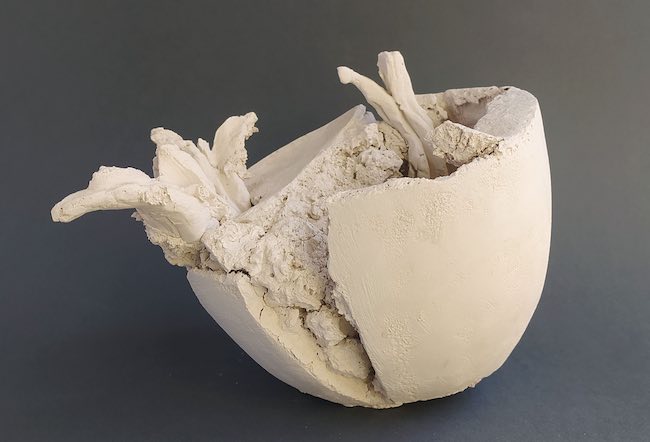

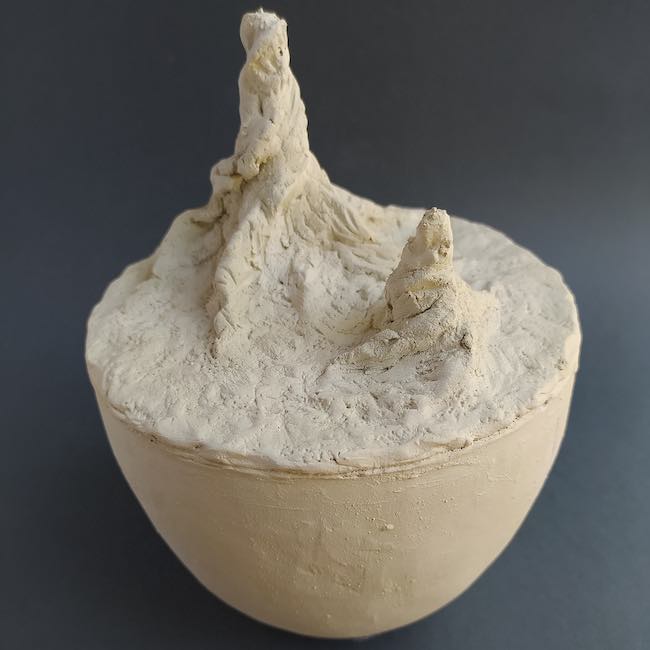

La necessità di andare oltre il visibile lo spinge verso l’interpretazione metaforica dando traccia della realtà poiché punto di partenza dell’esplorazione più interiore e profonda, ma poi si distacca dalla forma conosciuta perché consapevole che è solo attraverso l’elevazione verso l’essenza, verso il concetto, che è possibile raggiungere consapevolezze e nozioni di spessore più elevato rispetto a quello contingente. L’uovo per Nicolosi rappresenta il tutto da cui partire, la rassicurazione, la base certa che però non si trasforma mai in guscio, in corazza dentro la quale nascondersi impedendosi di spingersi verso la conoscenza, tutt’altro, in realtà le sue sculture mostrano l’esigenza di espansione verso l’esterno, in virtù della caratteristica di rappresentare solo una metà della forma, sovrastata poi da elementi più o meno figurativi che diventano manifestazioni interpretative del suo pensiero.

In altri casi invece, come nella scultura Mare dentro, realizzata ispirandosi al poema di Ramòn Sampedro, l’uovo rappresenta tutto ciò che può immobilizzare l’individuo, l’incapacità, o l’impossibilità, di staccarsi dalla contingenza facendosi intrappolare in una condizione dalla quale l’unica via d’uscita è il sogno, l’immaginazione, la fantasia di un movimento che di fatto non riesce a verificarsi. L’argilla bianca del guscio contiene il nero fumo del fluttuare delle acque, metafora di un’idea che però nella realtà non viene realizzata, ecco il motivo per cui l’emisfero ovoidale costituisce un limite oltre il quale il mare del titolo non riesce a spingersi.

Nell’opera Genesi-attraverso lo specchio, esposta nell’ambito della mostra Save Kalos presso la sede Unesco di Parigi, Franco Nicolosi riaffronta il concetto della nascita della natura, non importa se umana o vegetale, in grado di generare radici solide dalle quali poi crescere, sviluppare rami e foglie nel caso di un albero, o ampliare la conoscenza e il proprio posto nella società in virtù degli incontri e delle esperienze nel caso dell’essere umano. È forse questa la ragione per cui l’artista sceglie l’indistinto, l’indefinitezza per raccontare il germe della nascita al centro della metà dell’uovo, peraltro pieno come a sottolineare l’importanza della base da cui si cresce; attraverso l’irriconoscibilità della forma auspica che l’uomo possa riavvicinarsi a quella naturalezza, a quella capacità semplice e priva di ogni superbia o arroganza, caratteristiche tipicamente umane, di connettersi, creare reti di radici sottostanti al terreno e capaci di rompere persino il cemento con la loro forza, sottolineando quanto l’unione e la comunione d’intenti, che nel caso della natura sono quelli primordiali della sopravvivenza, possano vincere su qualsiasi forza esterna, anche se di apparente maggior resistenza.

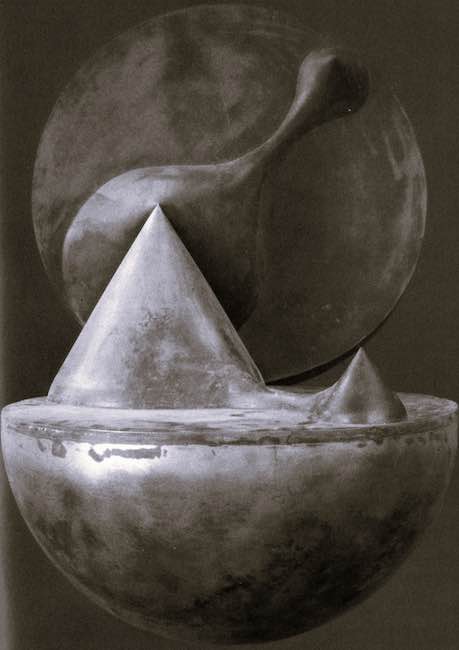

E ancora in Riflessioni di superficie Nicolosi parla di rifrazione, di punti di vista che possono essere reali o illusori sulla base della posizione di osservazione, relativi come in fondo lo è tutta la realtà a prescindere dalla convinzione dei più che esista un assolutismo di fatto erroneo; è questo il messaggio dell’artista, l’invito a sforzarsi di comprendere che spesso un’illusione può costituire la realtà tanto quanto la realtà si riveli invece un’illusione, dipende solo dall’approccio del singolo. La parte superiore della scultura può essere pertanto interpretata come specchio di quella inferiore o come realtà a se stante, solo casualmente vicina e somigliante, sottolineando in questo modo la sua tendenza al relativismo e alle possibilità quantiche.

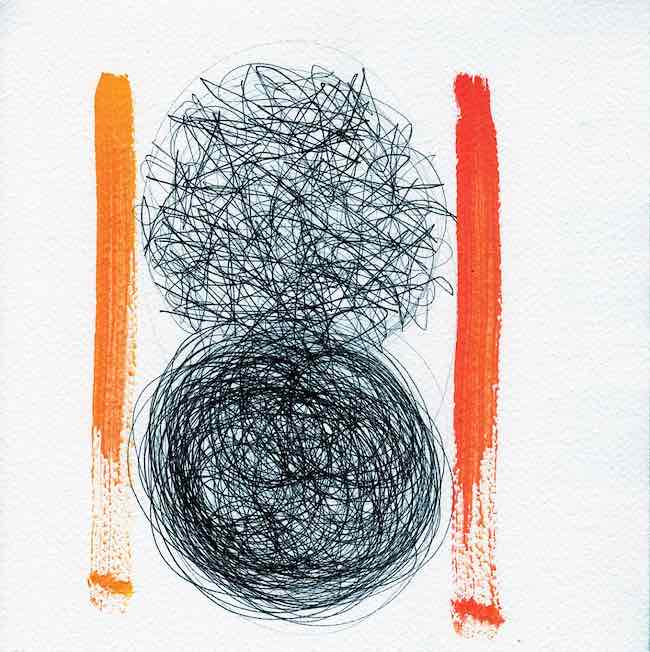

Anche nei disegni ciò che affascina Franco Nicolosi è la transizione, il passaggio, l’evoluzione, l’alternanza tra vuoti e pieni che in fondo costituisce l’eterno movimento della vita; Passaggi dell’anima è simbolico proprio del processo di snellimento che persino l’anima è in grado di compiere nel momento in cui realizza che alcune emozioni sono zavorre, fasi di dolore che devono essere allontanate se desidera elevarsi verso la leggerezza e la piacevolezza del sentire verso cui naturalmente tende.

Franco Nicolosi si divide tra la sua attività di docente e quella di artista, ha all’attivo la partecipazione a molte mostre collettive su tutto il territorio nazionale e una a Parigi, e alcune sue sculture hanno ricevuto premi e menzioni da giurie internazionali.

FRANCO NICOLOSI-CONTATTI

Email: nicolosifranco73@gmail.com

Sito web: https://franconicolosi.it/

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/franco.nicolosi.5

Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/in/franco-nicolosi-12203146/

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/nicolosi_franco/

The perpetual birth in the enigmatic sculptures by Franco Nicolosi

The automatism of regeneration that characterises nature has always constituted a sort of emblem, a propulsive thrust for man to seek the same approach for himself as well; art has not shied away from the fascination of studying birth, the starting impulse from which everything comes to life and which it has identified and iconised in the shape of the egg, recounted and reproduced in the various styles that have alternated over the centuries and which still today constitute a constant source of research and inspiration for contemporary authors. Today’s protagonist starts precisely from the ovoid form to explore today’s world and reflect on the existence of man and the things around him.

The attraction exerted by the egg on human beings and artists has primordial roots, because it has always imposed itself as the beginning of generation from an apparently fragile and liquid shell to give body to a life, thus associating itself with man’s need to invoke and yearn for the capacity to strive towards purity, towards perfection that finds its space in that ovoid form, protective but at the same time ready to open up to let a new existence flow. As early as the 15th century, Hieronymus Bosch, the early Symbolist forerunner of Surrealism for his disturbing images that are at the same time magnetic for their improbability, for their unreality, used the egg in many paintings, narrating it as a desire for a return to a dimension of peace, a new plunge towards that ancestral protection that in the society of the time, full of pitfalls, could not be found. Despite the fact that over the years many great artists such as Velazques and Bruegel, with their genre paintings, recounted images of everyday life in which eggs were in some way co-protagonists, and at the end of the 19th century Fabergé had decided to create his sumptuous and precious Eggs in honour of the Russian tsars, thus accentuating their aesthetic value, the sheer beauty of the form that could be enriched with details and workmanship to make it even more fascinating, it was necessary to wait until the beginning of the 20th century to rediscover the symbolic meaning of the ovoid shape that Bosch pioneered.

Surrealism in fact explored the deeper meaning of the egg from different points of view, meditative and ironic in René Magritte, more explicit and linked to carnality, regeneration and the rediscovery of a forgotten purity in Salvador Dalì. But even Giorgio De Chirico in his Metaphysical Art could not help but introduce it, decontextualising it, as an element of a timeless reality, just as Fontana in Spatialism addressed both its reference to fertility and its nihilism, the principle of nothingness, particularly in his series of canvases in which he depicted it full of holes, of openings. Photography, too, with another great exponent of contemporary Surrealism, Chema Madoz, tackled the theme of the egg as an exploratory symbol of reality, as a refuge but also as an element that can cast doubt on certainties. Turinese sculptor and draughtsman Franco Nicolosi makes the ovoid form the almost absolute protagonist of his sculptures with a strong metaphysical appeal, even if in some cases he tends towards Abstractionism, as well as of his drawings in which he tackles the relationship between emptiness and fullness, exalting its symbolism and all that the mind is stimulated to explore by virtue of the mystery of its hemispheres, which contain everything but which in reality also let out, as if the sense of protection were ephemeral or as if following the moment of birth it is necessary to propagate outwards the vital energy, the fruit of that generation so that it can relate to life.

White clay, terracotta, epoxy resin and steel are some of the materials preferred to give life to his sculptures, smoothing and painting their surfaces to suit the creative and communicative intent, letting the artworks be a means of disseminating thought, the sense of the whole, of the reflective and meditative approach that characterises the expressive philosophy of Nicolosi, a professor of Art and Theatre and Film Scenography and for this reason strongly oriented towards experimentation, towards the need to explore new techniques, new languages that can be functional in manifesting his interiority. The need to go beyond the visible pushes him towards metaphorical interpretation, giving a trace of reality as the starting point of the most interior and profound exploration, but then he detaches himself from the known form because he is aware that it is only through elevation towards the essence, towards the concept, that it is possible to reach awareness and notions of a higher depth than the contingent one. The egg for Nicolosi represents the whole from which to start, the reassurance, the certain base which, however, is never transformed into a shell, into an armour within which to hide, preventing oneself from pushing towards knowledge. On the contrary, his sculptures actually show the need to expand outwards, by virtue of the characteristic of representing only one half of the form, which is then surmounted by more or less figurative elements that become interpretative manifestations of his thought. In other cases, as in the sculpture Mare dentro (Sea inside), inspired by Ramòn Sampedro’s poem, the egg represents everything that can immobilise the individual, the inability, or impossibility, of detaching oneself from contingency by becoming trapped in a condition from which the only way out is dreaming, imagination, the fantasy of a movement that in fact cannot take place. The white clay of the shell contains the black smoke of the floating water, a metaphor for an idea that in reality is not realised, which is why the ovoid hemisphere constitutes a limit beyond which the sea of the title cannot go.

In the artwork Genesi-attraverso lo specchio (Genesis-across the mirror), exhibited during the Save Kalos exhibition at the Unesco headquarters in Paris, Franco Nicolosi re-addresses the concept of the birth of nature, no matter whether human or vegetable, capable of generating solid roots from which it then grows, developing branches and leaves in the case of a tree, or expanding knowledge and its place in society by virtue of encounters and experiences in the case of a human being. This is perhaps the reason why the artist chooses the indistinct, the indefinite to tell the story of the germ of birth at the centre of the half of the egg, moreover full as if to underline the importance of the base from which one grows; through the unrecognisability of the form, he hopes that man can get closer to that naturalness, to that simple capacity, devoid of any pride or arrogance, typically human characteristics, to connect, to create networks of roots beneath the ground and capable of breaking even concrete with their strength, underlining how union and communion of intentions, which in the case of nature are the primordial ones of survival, can win over any external force, even if of apparent greater resistance. And again in Riflessioni di superficie (Reflections of the surface), Nicolosi speaks of refraction, of points of view that can be real or illusory on the basis of the position of observation, relative as all reality basically is, regardless of the conviction of most that there is an absolutism which is in fact erroneous; this is the artist’s message, the invitation to strive to understand that often an illusion can constitute reality as much as reality turns out to be an illusion, it just depends on the individual’s approach.

The upper part of the sculpture can therefore be interpreted as a mirror of the lower part or as a reality in its own right, only casually close and similar, thus emphasising its tendency to relativism and quantum possibilities. In his drawings, too, what fascinates Franco Nicolosi is the transition, the passage, the evolution, the alternation between emptiness and fullness that ultimately constitutes the eternal movement of life; Passaggi dell’anima (Passages of the soul) is symbolic precisely of the streamlining process that even the soul is capable of performing when it realises that certain emotions are ballasts, phases of pain that must be removed if it wishes to rise towards the lightness and pleasantness of feeling towards which it naturally tends. Franco Nicolosi divides his time between his work as a teacher and as an artist. He has participated in many group exhibitions throughout Italy and one in Paris, and some of his sculptures have received prizes and mentions from international juries.