L’arte del Ventunesimo secolo pone i creativi davanti a diverse strade, tante quanti sono stati i movimenti pittorici che negli anni passati hanno avuto linee nette e definite per esprimere le caratteristiche specifiche che ciascuna corrente intendeva sottolineare. Con il trascorrere del tempo però quell’esigenza di marcare distinzioni e territori appartenenti a uno o all’altro gruppo artistico ha perso la sua valenza iniziale perché in fondo non è possibile imbrigliare un artista all’interno di confini troppo rigidi, né tanto meno sarebbe funzionale all’evoluzione dell’arte impedire le contaminazioni, le sinergie, le interazioni che proprio in virtù delle conoscenze e delle libertà espressive conquistate nei secoli precedenti hanno costituito una preziosa base da cui partire per creare qualcosa di nuovo, oppure per scegliere uno stile più tradizionale pur permeandolo delle sensazioni e delle emozioni viste attraverso il filtro dell’attualità. La protagonista di oggi, mantiene un forte legame con il passato espressivo pur riuscendo a mescolare nelle sue tele modernità e romanticismo, fascino e mistero di scenari senza tempo che in qualche modo si legano anche ai miti e alle leggende greche.

Il Diciannovesimo secolo costituì un periodo particolare nella storia dell’arte mondiale perché da un lato manteneva ancora molto forte il legame con lo stile accademico mentre dall’altro cominciava a spingersi verso un rapporto più profondo con la spiritualità, con le energie intorno all’essere umano, con quell’inspiegabile che sfuggiva alla razionalità dell’Illuminismo tanto celebrato nel secolo precedente, e cominciava a riportare l’essere umano al centro dell’osservazione degli artisti. Inizialmente il Romanticismo Inglese, quello di William Turner per intenderci, rivoluzionò l’approccio nei confronti del paesaggio sottolineando l’importanza e la forza della natura che ridimensionava l’uomo a semplice comprimario di ciò che di fatto il potere delle energie esterne esercitavano; qualche decennio dopo fu invece il Simbolismo a esplorare la profonda relazione tra essere umano e quella spiritualità, quel mistero che aleggiava oltre il visibile, oltre ciò che poteva essere spiegato perché conosciuto nella realtà contingente. Le tele di Odilon Redon, Gustave Moreau e Arnold Böcklin indagavano sul rapporto tra la vita e la morte, sulla profondità dei miti classici del passato contrapposti alla superficialità e alla mancanza di cultura della nuova classe borghese, sulla connessione tra sogno e realtà. Parallelamente però un altro gruppo di artisti manifestò al contrario l’esigenza di osservare ciò che apparteneva alla quotidianità con un atteggiamento più contemplativo, più epurato da ogni soggettività o interpretazione donando alle opere un aspetto familiare, reale, attinente a tutto ciò che l’occhio poteva cogliere; malgrado questa intenzione di base, di fatto con il trascorrere dei decenni il Realismo, questo il nome del movimento, cominciò a testimoniare le condizioni disagiate della classe operaia, delle persone meno abbienti, ma anche le lotte per la conquista di quei diritti che fino a quel momento erano stati ignorati dai proprietari di terre e di fabbriche. L’artista greca Ageliki Alexandridou mescola i due stili, Simbolismo e Realismo, per dar vita a un suo linguaggio personale e intimo che da un lato si veste di atmosfere mistiche o legate alle tradizioni e ai miti del suo paese, dall’altro abbandona il lato più sociale del Realismo spostandosi verso una morbidezza romantica che costituisce il suo punto di osservazione di ciò che la circonda.

Nelle sue opere la parte più cruda della realtà viene abbandonata per lasciare spazio a tutta la delicatezza che contraddistingue alcuni frangenti, alcuni istanti o le persone che di quel fotogramma emotivo sono protagoniste; la gamma cromatica diviene mezzo funzionale a esprimere quella sensibilità che inevitabilmente fuoriesce dai volti ritratti, dal modo in l’artista osserva i bambini o le donne, che appartengono a un mondo leggero, tenue e puro se osservate nella loro spontaneità. Ageliki Alexandridou sembra spiare le espressioni più significative dell’attimo che sceglie di immortalare, infondendo all’immagine finale una sensazione di solennità accresciuta dal riferimento ai simboli che spesso accompagnano e contraddistinguono i protagonisti delle sue tele.

Gioca con la luce e con le ombre l’artista, sfumando il colore per infondere quell’atmosfera ovattata con la quale avvolge le figure e gli scenari in cui le colloca, come se le loro emozioni, il loro sentire, fossero accompagnati dall’ambiente circostante, dal cielo, dalle acque, dagli sfondi che li circondano. Quando racconta i miti invece Ageliki Alexandridou permea le sue tele di mistero, di una particolare magia che induce l’osservatore a immaginare il potere degli dei, quel loro essere al di sopra degli umani pur volendo in qualche modo far parte della loro vita.

E dunque l’artista descrive le Nereidi languidamente adagiate sugli scogli durante la notte o alla luce fioca dell’alba, per nascondersi pur avendo l’illusione di essere entrate per poco tempo in quella vita che osservano da lontano; è proprio questo il senso del dipinto The stars above (Le stelle sopra), in cui le bellissime donne si lasciano cullare dal rumore delle onde del mare, con la luce della luna che sembra vegliare su di loro. Malgrado la scena sia evidentemente notturna, l’artista riesce a rappresentare perfettamente l’intenso chiarore che nel plenilunio si sprigiona, perché nella sua pittura anche il buio ha una sua luce. I dettagli non sono sottolineati poiché ciò che è più importante è la visione d’insieme, quella purezza surreale espressa dai corpi nudi e dai lunghi capelli che contraddistinguono le donne.

Nella tela Innocence (Innocenza) Ageliki Alexandridou affronta uno dei temi che ama di più, quello dell’infanzia, un’età magica in cui la purezza e la spontaneità non sono ancora state erose dalla quotidianità, dagli eventi e dalle vicissitudini che inducono l’adulto a cambiare punto di vista e approccio alla vita; in questa tela le due piccole ballerine guardano curiose ciò che è intorno a loro, inconsapevoli di quanto quelle ali indossate per un saggio di danza corrispondano alla loro essenza, alla capacità di osservare tutto con lo sguardo della meraviglia, della sorpresa, della fiducia che tutto andrà bene e che il futuro sarà meraviglioso. In questa tela emerge la tendenza al Simbolismo della Alexandridou poiché ritrarre le due fanciulle con ali d’angelo collocandole al di fuori del contesto dove dovrebbero trovarsi, il palcoscenico, sembra suggerire all’osservatore quanto i bambini siano simili agli angeli che silenziosamente accompagnano il nostro cammino nella vita.

Anche in Detecting beauty rende una tenera bimba protagonista di un frangente sospeso, in questo caso sfumando lo sfondo proprio per dare il senso di morbidezza, di delicatezza associata a una farfalla, come se quest’ultima percependo la purezza della giovane protagonista non avesse timore ad avvicinarsi a lei; qui la gamma cromatica è cipriata, prevalgono i toni del bianco, del beige, del carne e del rosso chiaro dei capelli, ai quali si armonizza anche lo sfondo, come se l’artista volesse mantenere una cornice in perfetto equilibrio con il suo personaggio.

In A moody day (Una giornata lunatica) Ageliki Alexandridou riprende il tema della donna, in questo caso moderna, non più legata al mito bensì alla quotidianità che però non la rende meno magica e poetica delle dee o semidee anzi, forse quel suo essere disturbata dalla pioggia, quel suo procedere spedita in stivali e minigonna, la fa apparire persino più affascinante, enigmatica, dinamica eppure a suo modo sinuosa e femminile tanto quanto le antiche Nereidi. Il cielo plumbeo non riesce a spegnere la luce che la donna, forse inconsapevolmente, porta con sé e che l’artista evidenzia a dispetto della lunaticità, raccontata con il titolo, che avvolge la donna in quel giorno di pioggia.

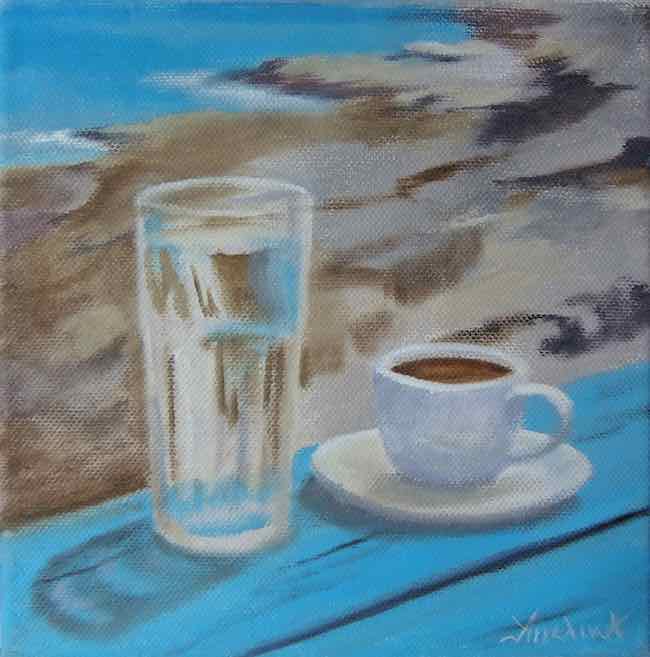

Il suo stile realista in equilibrio sulla luce si svela anche con le nature morte, come Greek morning! (Mattino greco) in cui non riesce a rinunciare a narrare il turchese che contraddistingue il suo paese, un caffè e un bicchiere d’acqua, forse un attimo dopo la colazione, o semplicemente durante una pausa di metà mattina, con davanti l’incantevole vista dell’azzurro del mare. Purezza, semplicità, magia e sogno sono le linee fondamentali della pittura di Ageliki Alexandridou che ha iniziato a dipingere nel 2011 ricevendo subito consensi dal pubblico e dagli esperti; ha all’attivo la partecipazione a molte mostre collettive in tutta la Grecia e le sue opere fanno parte di collezioni private a Melbourne, New York, Medio Oriente, Europa e in edifici pubblici in Grecia.

AGELIKI ALEXANDRIDOU-CONTATTI

Email: angelikaart8@gmail.com

Sito web: www.ageliki.com

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/AgelikiAlexandridou

Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/in/ageliki-alexandridou-505585a2/

Ageliki Alexandridou’s soft Realism suspended between Symbolist atmospheres and a romantic look at observed reality

Twenty-first century art confronts creative artists with different paths, as many as there have been pictorial movements in the past that have had clear and defined lines to express the specific characteristics that each current intended to emphasise. With the passage of time, however, that need to mark out distinctions and territories belonging to one or another artistic group has lost its initial value because, after all, it is not possible to harness an artist within boundaries that are too rigid, nor would it be functional to the evolution of art to prevent contaminations, the synergies, the interactions that precisely by virtue of the knowledge and expressive freedoms gained in previous centuries have constituted a valuable basis from which to create something new, or to choose a more traditional style while permeating it with sensations and emotions seen through the filter of current events. Today’s protagonist maintains a strong link to the expressive past while managing to mix modernity and romanticism, charm and mystery of timeless scenarios that are also somehow linked to Greek myths and legends in her paintings.

The 19th century constituted a special period in the history of world art because on the one hand it still retained very strong ties with the academic style while on the other it began to move towards a deeper relationship with spirituality, with the energies around the human being, with that inexplicable which escaped the rationality of the Enlightenment so much celebrated in the previous century, and began to bring the human being back to the centre of artists’ observation. Initially, English Romanticism, that of William Turner to be precise, revolutionised the approach to the landscape by emphasising the importance and power of nature, which reduced man to a mere secondary player in what the power of external energies actually exerted; a few decades later it was Symbolism that explored the profound relationship between the human being and that spirituality, that mystery that hovered beyond the visible, beyond what could be explained because it was known in contingent reality. The canvases of Odilon Redon, Gustave Moreau and Arnold Böcklin investigated the relationship between life and death, the depth of classical myths of the past set against the superficiality and lack of culture of the new bourgeois class, the connection between dream and reality. At the same time, however, another group of artists manifested the need to observe that which belonged to the everyday with a more contemplative attitude, more purged of any subjectivity or interpretation, giving the artworks a familiar, real aspect, relevant to everything the eye could grasp; despite this basic intention, in fact with the passing of decades Realism, this was the name of the movement, began to bear witness to the poor conditions of the working class, of the less well-off, but also to the struggles for the conquest of those rights that until then had been ignored by land and factory owners.

The Greek artist Ageliki Alexandridou mixes the two styles, Symbolism and Realism, to give life to her own personal and intimate language that on the one hand is dressed in mystical atmospheres or linked to the traditions and myths of her country, while on the other hand she abandons the more social side of Realism, moving towards a romantic softness that constitutes her point of observation of her surroundings. In her paintings, the crudest part of reality is abandoned to leave room for all the delicacy that characterises certain moments, certain instants or the people who are the protagonists of that emotional photogram; the chromatic range becomes a functional means of expressing that sensitivity that inevitably emerges from the faces portrayed, from the way the artist observes children or women, who belong to a light, tenuous and pure world when observed in their spontaneity. Ageliki Alexandridou seems to spy the most significant expressions of the moment she chooses to immortalise, infusing the final image with a sensation of solemnity heightened by reference to the symbols that often accompany and distinguish the protagonists of her canvases. The artist plays with light and shadows, blurring the colour to instil that muffled atmosphere with which she envelops the figures and the scenarios in which she places them, as if their emotions, their feeling, were accompanied by the surrounding environment, the sky, the waters, the backgrounds that surround them. When she tells myths, on the other hand, Ageliki Alexandridou permeates her canvases with mystery, with a special magic that induces the observer to imagine the power of the gods, their being above humans while somehow wanting to be part of their lives. And so the artist depicts the Nereids languidly lying on the rocks at night or in the dim light of dawn, hiding themselves while having the illusion of having briefly entered that life they observe from afar; this is precisely the meaning of the painting The stars above, in which the beautiful women are lulled by the sound of the waves of the sea, with the light of the moon seemingly watching over them. Although the scene is evidently nocturnal, the artist succeeds perfectly in depicting the intense glow that emanates from the full moon, because in her paintings even darkness has its own light.

The details are not emphasised because what is most important is the overall vision, that surreal purity expressed by the naked bodies and long hair of the women. In the canvas Innocence, Ageliki Alexandridou addresses one of the themes she loves most, that of childhood, a magical age in which purity and spontaneity have not yet been eroded by everyday life, by the events and vicissitudes that cause adults to change their point of view and approach to life; in this canvas, the two little dancers look curiously at what is around them, unaware of how much those wings worn for a dance recital correspond to their essence, to the ability to observe everything with the gaze of wonder, of surprise, of confidence that everything will be fine and that the future will be wonderful. Emerges Alexandridou’s tendency towards Symbolism in this canvas, as portraying the two girls with angel wings by placing them outside the context where they should be, the stage, seems to suggest to the viewer how similar the children are to the angels who silently accompany us on our journey through life. Also in Detecting Beauty, she makes a tender child the protagonist of a suspended moment, in this case blurring the background precisely to give the sense of softness, of delicacy associated with a butterfly, as if the latter, perceiving the purity of the young protagonist, was not afraid to approach her; here the colour palette is powdery, prevail the white, beige, flesh pink and the light red of the hair, with which the background also harmonises, as if the artist wanted to maintain a frame in perfect balance with her character. In A moody day, Ageliki Alexandridou takes up the theme of the woman, in this case a modern woman, no longer tied to myth but to everyday life, which does not, however, make her any less magical and poetic than the goddesses or demi-goddesses; on the contrary, perhaps her being disturbed by the rain, her hurried progress in boots and miniskirt, makes her appear even more fascinating, enigmatic, dynamic and yet in her own way as sinuous and feminine as the ancient Nereids. The leaden sky fails to extinguish the light that the woman, perhaps unconsciously, carries with her and that the artist highlights in spite of the moodiness, told by the title, that envelops the woman on that rainy day. Her realist style balanced by light is also revealed in the still lifes, such as Greek Morning, in which she does not fail to narrate the turquoise that characterises her country, a coffee and a glass of water, perhaps a moment after breakfast, or simply during a mid-morning break, with the enchanting view of the blue sea in front of her. Purity, simplicity, magic and dreams are the fundamental lines of Ageliki Alexandridou’s painting. She started painting in 2011 and immediately received acclaim from the public and experts; she has participated in many group exhibitions throughout Greece and her artworks are part of private collections in Melbourne, New York, the Middle East, Europe and in public buildings in Greece.