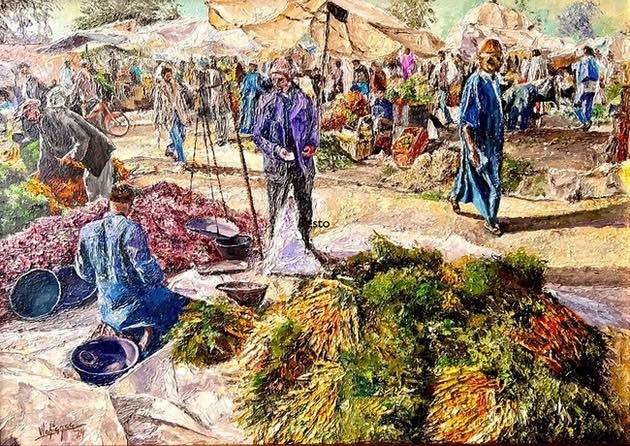

Raccontare tutto ciò che compone la realtà circostante richiede una sensibilità osservativa che va oltre lo sguardo distratto di cui l’essere umano si avvale nella sua quotidianità, perché ogni dettaglio, ogni piccolo particolare è di fatto una parte essenziale per dare il senso dell’insieme che rende unica e irripetibile una determinata scena; gli artisti che scelgono la narrazione dell’oggettività visibile hanno la capacità di riprodurre gli istanti davanti ai loro occhi arricchendoli di quell’emozione percettiva che essi stessi hanno provato nel momento in cui l’attenzione è stata catturata da uno scorcio, da una luce speciale che modificava il paesaggio o da un dettaglio che lo rendeva speciale solo in quell’unico frangente. Il protagonista di oggi, pur utilizzando uno stile fortemente legato alla realtà davanti a sé, lo interpreta con una tecnica in virtù della quale l’immagine viene frammentata e al contempo consolidata, quasi resa più concreta per evidenziarne la forza espressiva che dall’interiorità dell’autore giunge e investe l’osservatore.

Intorno alla metà dell’Ottocento, inizialmente in Francia ma poi in tutto il mondo occidentale, cominciò a delinearsi un’attenzione particolare verso la realtà sociale che determinò un desiderio di immortalare la vita quotidiana nelle strade delle città, in quelle classi meno abbienti che di fatto erano il motore della società e il vero segreto del successo dei proprietari di terre e di fabbriche; il Realismo si propose pertanto di spostare l’attenzione dagli interni nobili ed ecclesiastici e dai simboli allegorici e mitologici della pittura dei periodi precedenti, per focalizzarsi invece sulle storie di vita che si svolgevano sotto gli occhi degli artisti che scelsero di aderire al movimento. Gustave Courbet fu anticipatore di una stagione pittorica che si consolidò in virtù delle rivoluzioni sociali degli anni Cinquanta del Diciannovesimo secolo divenendo così testimonianza di un cambiamento dei tempi; Giuseppe Pellizza da Volpedo in Italia e il muralismo messicano di cui fu capostipite il maestro Diego Rivera, dipinsero dei capolavori in cui la maestria osservativa degli autori si mescolava all’intensità delle lotte di classe e delle rivoluzioni civili dei protagonisti delle loro opere. Contestualmente vi furono anche interpreti che vollero soffermarsi sulla pura contemplazione dei paesaggi, immortalando scorci in qualche modo vicini all’Arte Romantica di John Constable ma privati di quel sentimento nostalgico di cui le opere del maestro inglese erano invece intrise; anche negli Stati Uniti il Realismo ebbe una connotazione più morbida volta a immortalare i frammenti di vita nelle vie delle nuove metropoli che stavano nascendo, perdendo però la definizione perfetta delle immagini per spostarsi verso una maggiore emozionalità che spesso tralasciava l’attenzione ai dettagli per porre l’accento sull’atmosfera generale. Al Realismo Americano del periodo tra fine Ottocento e inizi Novecento appartenevano George Bellows, osservatore della vita quotidiana, Robert Henri, forse il più affascinato dal via vai cittadino e dalle strade trafficate, il cui tratto è indefinito e frastagliato nella pennellata, Joan Sloan che amava raccontare i momenti di convivialità all’interno dei locali dell’America di quel tempo e che fu ispiratore delle atmosfere intense e solitarie del grande Edward Hopper, quello che più di tutti influenzò la pittura figurativa successiva. La necessità di tornare alla contemplazione della realtà fu la spinta propositiva che indusse il Gruppo Novecento di Milano, e la Scuola Romana, a dare vita a un tipo di arte che si distaccasse dagli stravolgimenti delle avanguardie dei primi anni del Ventesimo secolo per abbandonare gli estremi cubisti e futuristi e ricominciando a rappresentare una quotidianità che doveva essere più chiara e descrittiva del loro tempo. L’artista Vincenzo Labianca, nato in Etiopia ma cresciuto a Roma dove vive e opera, ha una cifra stilistica fortemente legata al Realismo che tuttavia, come lo statunitense Robert Henri, mostra la necessità di dare maggiore concretezza alle tele frammentando il tratto grazie all’utilizzo della spatola, per dare rilievo a tutti quei dettagli essenziali per la composizione e che in tal modo divengono vivi, infondendo una sensazione di sottile movimento all’interno del fermo immagine in cui il tempo è sospeso a metà tra l’osservazione e la memoria.

La gamma cromatica è vivida e sempre accompagnata da una luce che tuttavia non è assoluta, si declina sulla base del paesaggio, dell’istante osservato, del luogo che di volta in volta è protagonista della tela; Vincenzo Labianca, in virtù della professione di architetto rilevatore, ha avuto l’opportunità di risiedere per lunghi periodi di tempo in paesi esteri come Yemen, Iran, Algeria, e da quei luoghi ha assorbito ricordi, odori e atmosfere che si sono insediati nel suo scrigno emotivo amplificandosi e incrementando una sensibilità osservativa poi riversata negli scorci e nelle scene di vita raccontate.

Da un lato dunque la contemplazione di momenti presenti, di cui riesce a esaltare la vivacità dinamica pur mostrando un fotogramma che in qualche modo testimonia l’inclinazione a rendere immortale quel preciso e irripetibile istante del frangente dell’osservazione, dall’altro però anche una tendenza a ripercorrere nostalgicamente i percorsi effettuati raccontando tutto ciò che aveva suscitato meraviglia nel suo sguardo di viaggiatore e di scopritore di civiltà lontane e diverse dalla propria.

E poi vi sono le tele sospese nel tempo, immagini di un passato semplice e spontaneo, forse immaginato oppure vissuto, in cui a essere protagonisti sono uomini e donne di cui Vincenzo Labianca sottolinea l’immediatezza espressiva priva di qualsiasi tipo di vanità o di desiderio di mettersi in mostra; è esattamente a questo gruppo di tele che appartiene Il contadinello, colto di sorpresa dall’autore nel momento in cui sta svolgendo il suo compito quotidiano di raccogliere i fasci di grano per raggrupparli in covoni. Il ragazzo sorride all’osservatore, quasi volesse comunicare il suo imbarazzo e in qualche modo l’incredulità per aver suscitato l’interesse di qualcuno compiendo solo le sue azioni quotidiane. Il tocco della spatola, sapientemente usata da Vincenzo Labianca, diviene fortemente evidente proprio nelle spighe di grano e anche sullo sfondo da cui si intravedono altre persone che stanno lavorando come il giovane rendendo così la scena concreta, come può esserlo solo chi lavora con la terra, e al contempo volatile in virtù di quel contatto con la natura che potrebbe modificare l’aspetto del tutto solo attraverso un soffio di vento.

L’opera I fenicotteri si riallaccia invece ai luoghi dei suoi viaggi, a quei paesaggi selvaggi in cui la natura regna incontaminata e protetta da qualsiasi azione dell’uomo, spesso distruttiva, e che si sono impressi nella sua memoria emozionale con tutta la loro bellezza; il lago dove gli splendidi uccelli rosa vivono è tranquillo, sereno, ed è esattamente questa la sensazione che viene trasmessa da Vincenzo Labianca a fruitore, il quale si immerge letteralmente nell’atmosfera descritta quasi ascoltandone il silenzio rotto solo dal suono degli animali e dalle zampe degli uccelli nella superficie lacustre. Anche qui l’apporto della spatola è essenziale per rendere frammentata l’immagine complessiva, quasi il riflesso dell’acqua e della luce richiedessero di essere messi in evidenza, di divenire co-protagonisti della scena per sottolineare quanto l’equilibrio spontaneo del mondo che ospita l’essere umano sia inimitabile e generi un’armonia in cui qualsiasi azione andrebbe a comprometterne la perfezione. Lo sguardo dell’autore appare rapito e ammirato, circospetto poiché anche il minimo rumore potrebbe spaventare gli animali modificando quella scena affascinante.

Vele nel porticciolo sottolinea invece il senso di libertà e di sogno che le barche e il mare da sempre suscitano nell’immaginario comune, perché di fatto partire equivale ad andare verso una conoscenza profonda di se stessi, tanto quanto l’acqua è un elemento di rigenerazione, di modifica e di trasformazione poiché il suo flusso non può essere arrestato. Questa tela costituisce dunque un’allegoria del senso della vita, le piccole vele ormeggiate nel porto sembrano raccontare il corso di un’esistenza che inizia nella comunità, nel gruppo, ma poi per evolvere e formarsi necessita di allontanarsi rendendosi autonomi, percorrendo un viaggio in solitaria alla scoperta di tutto ciò che senza quel distacco non sarebbe possibile conoscere e apprendere. La luce è intensa, sembra appartenere al pieno pomeriggio, e si riflette sulle acque tranquille della baia dando l’impressione di quel leggero galleggiare che però nello sguardo di Vincenzo Labianca ha bisogno di restare immobile perché è esattamente in quel fermo immagine che si nasconde il respiro di pace e di libertà da egli provato quando ha avuto la scena davanti ai suoi occhi.

La spigolatrice e Natura morta appartengono invece al lato più tradizionale della pittura dell’autore, dove il Realismo prevale e l’alternanza tra luci e ombre sottolineano l’intensità delle scene stimolando la contemplazione dei dettagli; qui il tuffo è verso un passato più lontano, evidente dell’abito della ragazza della prima opera, quasi volesse suggerire l’importanza di non dimenticare mai da dove veniamo per comprendere meglio dove vogliamo andare. Vincenzo Labianca ha al suo attivo un’importante mostra personale scuderie di Palazzo Morenberg nel centro storico di Sarnonico (TN) e la partecipazione a mostre collettive a Roma, Palermo, Firenze, Bari e Padova. È socio onorario dell’Associazione Cento Pittori di via Margutta e socio ordinario dell’Associazione Art Studio Tre.

VINCENZO LABIANCA-CONTATTI

Email: v.labianca1941@gmail.com

Facebook: www.facebook.com/vincenzo.labianca.58

Instagram: www.instagram.com/vincenzo.labianca1941/

Linkedin: www.linkedin.com/in/vincenzo-labianca-95668931/

Telling everything that makes up the surrounding reality requires an observational sensitivity that goes beyond the distracted gaze that human beings make use of in their daily lives, because every detail, every small particular is in fact an essential part in giving the sense of the whole that makes a certain scene unique and unrepeatable; artists who choose the narrative of visible objectivity have the ability to reproduce the instants before their eyes by enriching them with the perceptual emotion that they themselves felt at the moment when their attention was caught by a glimpse, by a special light that altered the landscape or by a detail that made it special only at that one juncture. Today’s protagonist, while using a style strongly linked to the reality in front of him, interprets it with a technique by virtue of which the image is fragmented and at the same time consolidated, almost made more concrete in order to highlight the expressive force that from the author’s interiority reaches and invests the viewer.

Around the middle of the nineteenth century, initially in France but then throughout the Western world, there began to emerge a particular attention to social reality that resulted in a desire to immortalize daily life in the streets of cities, in those less affluent classes that were in fact the driving force of society and the real secret of the success of land and factory owners; Realism therefore set out to shift its attention away from the noble and ecclesiastical interiors and the allegorical and mythological symbols of the painting of earlier periods, and to focus instead on the stories of life that unfolded before the eyes of the artists who chose to join the movement. Gustave Courbet was the forerunner of a pictorial season that was consolidated by virtue of the social revolutions of the 1850s, thus becoming a witness to a change of the times; Giuseppe Pellizza da Volpedo in Italy and Mexican muralism, of which the master Diego Rivera was the progenitor, painted masterpieces in which the observational skill of the authors mingled with the intensity of the class struggles and civil revolutions of the protagonists of their artworks.

At the same time there were also interpreters who wanted to dwell on the pure contemplation of landscapes, immortalizing glimpses somewhat close to John Constable‘s Romantic Art but deprived of the nostalgic feeling with which the works of the English master were instead imbued; in the United States, too, Realism had a softer connotation aimed at immortalizing the fragments of life on the streets of the new metropolises that were springing up, losing, however, the perfect definition of the images and moving toward a greater emotionality that often left out attention to detail to emphasize the general atmosphere. To the American Realism of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries belonged George Bellows, an observer of everyday life, Robert Henri, perhaps the most fascinated by the bustle of the city and busy streets, whose trait is indefinite and jagged in the brushstroke, Joan Sloan who loved to recount the moments of conviviality within the clubs of America at that time and who was the inspiration for the intense and solitary atmospheres of the great Edward Hopper, the one who most influenced later figurative painting.

The need to return to the contemplation of reality was the purposeful impetus that led the Novecento Group of Milan, and the Roman School, to give life to a type of art that would break away from the upheavals of the avant-gardes of the early twentieth century and abandon the Cubist and Futurist extremes and begin again to represent an everyday life that was to be clearer and more descriptive of their time. The artist Vincenzo Labianca, who was born in Ethiopia but grew up in Rome where he lives and works, has a stylistic trait strongly linked to Realism that nevertheless, like the American Robert Henri, shows the need to give greater concreteness to the canvases by fragmenting the stroke thanks to the use of the spatula, in order to give prominence to all those details that are essential to the composition and that in this way become alive, infusing a feeling of subtle movement within the still image in which time is suspended somewhere between observation and memory.

The chromatic range is vivid and always accompanied by a light that nevertheless is not absolute, it declines on the basis of the landscape, the instant observed, the place that from time to time is the protagonist of the canvas; Vincenzo Labianca, by virtue of his profession as a surveyor architect, had the opportunity to reside for long periods of time in foreign countries such as Yemen, Iran, Algeria, and from those places he absorbed memories, smells and atmospheres that have settled in his emotional treasure chest amplifying and increasing an observational sensitivity then poured into the glimpses and scenes of life recounted. On the one hand, therefore, the contemplation of present moments, of which he manages to exalt the dynamic vivacity while showing a photogram that somehow testifies to the inclination to make immortal that precise and unrepeatable instant of the juncture of the observation, on the other hand, however, also a tendency to nostalgically retrace the paths taken recounting everything that had aroused wonder in his gaze of a traveler and discoverer of distant civilizations different from his own.

And then there are the canvases suspended in time, images of a simple and spontaneous past, perhaps imagined or lived, in which the protagonists are men and women whose expressive immediacy Vincenzo Labianca underlines, devoid of any kind of vanity or desire to show off; it is exactly to this group of canvases that belongs Il contadinello (The little peasant), caught by surprise by the author at the moment when he is carrying out his daily task of gathering bundles of wheat to group them into sheaves. The boy smiles at the observer, as if to convey his embarrassment and somehow disbelief that he has aroused someone’s interest by accomplishing only his daily actions. The touch of the spatula, skillfully used by Vincenzo Labianca, becomes strongly evident precisely in the ears of wheat and also in the background from which can be glimpsedd other people who are working like the young man, thus making the scene concrete, as only those who work with the land can be, and at the same time volatile by virtue of that contact with nature that could change the appearance of everything only through a breath of wind.

The work I fenicotteri (The Flamingos), on the other hand, reconnects with the places of his travels, those wild landscapes where nature reigns unspoiled and protected from any human action, often destructive, and which have imprinted in his emotional memory with all their beauty; the lake where the splendid pink birds live is peaceful, serene, and this is exactly the feeling that is conveyed by Vincenzo Labianca to the viewer, who literally immerses himself in the described atmosphere almost listening to the silence broken only by the sound of the animals and the feet of the birds in the lake surface. Here, too, the contribution of the palette knife is essential to make the overall image fragmented, almost as if the reflection of the water and the light required to be highlighted, to become co-stars of the scene to emphasize how the spontaneous balance of the world that hosts the human being is inimitable and generates a harmony in which any action would compromise its perfection.

The author’s gaze appears enraptured and admiring, circumspect since even the slightest noise could frighten the animals by altering that fascinating scene. Vele nel porticciolo (Sails in the marina), on the other hand, emphasizes the sense of freedom and dreaming that boats and the sea have always aroused in the common imagination, because in fact leaving is tantamount to moving toward a profound knowledge of oneself, just as much as water is an element of regeneration, modification and transformation since its flow cannot be stopped. This canvas thus constitutes an allegory of the meaning of life, the small sails moored in the harbor seem to tell the course of an existence that begins in the community, in the group, but then in order to evolve and form itself needs to move away by becoming autonomous, traveling on a solitary journey to discover all that without that detachment it would not be possible to know and learn.

The light is intense, it seems to belong to the middle of the afternoon, and it is reflected on the calm waters of the bay giving the impression of that slight floating that, however, in Vincenzo Labianca‘s gaze needs to remain still because it is exactly in that image that is hidden the breath of peace and freedom he felt when he had the scene before his eyes. La spigolatrice (The Gleaner) and Natura morta (Still Life), on the other hand, belong to the more traditional side of the author’s painting, where Realism prevails and the alternation of light and shadow emphasize the intensity of the scenes by stimulating the contemplation of details; here the plunge is into a more distant past, evident in the dress of the girl in the first work, as if to suggest the importance of never forgetting where we come from in order to better understand where we want to go. Vincenzo Labianca has to his credit an important solo exhibition scuderie di Palazzo Morenberg in the historic center of Sarnonico (TN) and participation in group exhibitions in Rome, Palermo, Florence, Bari and Padua. He is an honorary member of the Cento Pittori di via Margutta Association and an ordinary member of the Art Studio Tre Association.

L'Opinionista® © since 2008 Giornale Online

Testata Reg. Trib. di Pescara n.08/08 dell'11/04/08 - Iscrizione al ROC n°17982 del 17/02/2009 - p.iva 01873660680

Pubblicità e servizi - Collaborazioni - Contatti - Redazione - Network -

Notizie del giorno -

Partners - App - RSS - Privacy Policy - Cookie Policy

SOCIAL: Facebook - X - Instagram - LinkedIN - Youtube