La società attuale, ingannevolmente stabile e concentrata sulla corsa verso le innovazioni e verso le tecnologie, si trova inspiegabilmente spesso destabilizzata, come se tutte le certezze su cui ha basato la sua esistenza fossero solo illusoriamente solide e concrete, mentre la realtà pone invece l’essere umano davanti alla caducità, all’effimero che contraddistingue alcune basi del vivere odierno che possono però crollare da un momento all’altro. Questo tipo di insicurezza è tornato più volte nel corso della storia dell’arte, e sempre in occasione dei conflitti dove tutte le certezze erano state messe in discussione dagli eventi esterni all’individuo; ed è sulla base di questa costante instabilità appartenente anche alla contemporaneità, che viene ideato da Piero Campanini e Stefano Paulon, il progetto Rigore e Psiche dove le loro opere divergenti dal punto di vista stilistico, divengono assolutamente convergenti e in dialogo sul concetto di base, quello appunto della necessità dell’essere umano di trovare un bilanciamento, un centro di se stesso senza il quale è impossibile restare in piedi.

Nel corso del Novecento, le due grandi guerre hanno generato da un lato un atteggiamento di distacco completo dalla realtà osservata proprio per generare un allontanamento da parte degli artisti dalle atrocità a cui avevano assistito, dando vita a un tipo di arte, l’Astrattismo, che fungeva quasi da rifugio in virtù della sua scientificità, del suo concentrarsi solo e unicamente sul gesto plastico e sulla ricerca dell’equilibrio perfetto affidato al rigore geometrico, come nel De Stijl e nel Suprematismo, poi evoluti nell’Astrattismo Geometrico. Questo tipo di linguaggio mostrava la necessità da parte degli esponenti dei vari movimenti, da Piet Mondrian e Theo Van Doesburg a Kasimir Malevic per finire a Manlio Rho e Mario Radice, di contenere, di arginare quel mondo emotivo che diversamente avrebbe finito per travolgerli, mentre al contrario, astraendosi da esso potevano continuare a generare arte mantenendo l’estraniazione dalla realtà circostante. Un’altra reazione espressiva, altrettanto rilevante e necessaria per oltrepassare i momenti bui della guerra, fu quella del Surrealismo dove gli interpreti trasposero sulla tela tutte le angosce, le inquietudini e gli incubi delle persone che avevano assistito alla distruzione e alla devastazione dei combattimenti; seguendo e traducendo in immagini gli studi di Sigmund Freud, le analisi sull’inconscio dei reduci profondamente segnati dalle atrocità compiute o subite, i maestri come Salvador Dalì e Max Ernst riprodussero scene apocalittiche e decontestualizzate dove lo sguardo veniva ingannato dallo stile pittorico perfettamente figurativo salvo poi trovarsi davanti a mostri terrificanti e animali composti da parti umane, mentre altri come René Magritte e Paul Delvaux invece si spostarono più verso una riflessione, un’analisi sul senso dell’esistenza, sul significato profondo e sottile che si nasconde dietro ogni circostanza, ogni oggetto, ogni contesto, per scoprirne il mistero. I tempi di pace della seconda metà del Novecento, almeno per quanto concerneva i territori del cosiddetto occidente, indussero gli artisti ad avvicinarsi ai temi sociali, quelli delle disuguaglianze e dell’emarginazione particolarmente evidenti nelle grandi città statunitensi, e alle lotte per i diritti, ma soprattutto ciò che contraddistinse l’arte di quegli anni fu la spinta ad andare verso le persone, verso un pubblico magari meno colto ma sicuramente più aperto alla comprensione delle dinamiche sociali come quelle trattate dalla Street Art o dalla Pop Art, una più dissacrante, l’altra più ironicamente celebrativa. Nella contemporaneità, l’essere umano ha acquisito certezze che via via si sono dimostrate più effimere, poiché la società è apparentemente rimasta legata ai progressi e al benessere dei tardi anni Novanta, mentre di fatto tutto ha cominciato a tendere verso l’illusione che il progresso tecnologico fosse la panacea a tutte le difficoltà inducendo l’essere umano a dimenticare di rimanere umano.

È in questo cardine che si innesca il progetto Rigore e Psiche, l’approfondimento di Piero Campanini e di Stefano Paulon nei confronti di tutto ciò che appartiene alla disequilibrata esistenza attuale, quella dove l’individuo non può più fare a meno di fare i conti con la consapevolezza delle difficoltà del mantenere un bilanciamento con se stesso, in virtù di esperienze compiute che lo hanno messo di fronte a imprevedibili cadute le quali hanno poi richiesto lo sforzo di rialzarsi e di prendere coscienza della propria fragilità. Diversi eppure complementari, Piero Campanini e Stefano Paulon interpretano in maniera simmetrica l’instabilità del vivere attuale ma al contempo il bisogno di trovare un modo per mantenersi in bilico, resistendo alla caduta ma soprattutto trovando quel centro, quel fragile equilibrio che troppo spesso sfugge a causa delle circostanze che si susseguono.

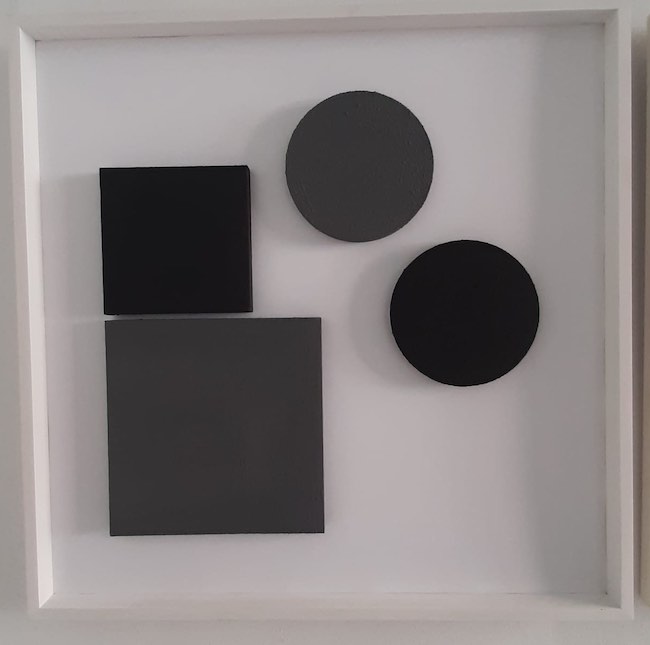

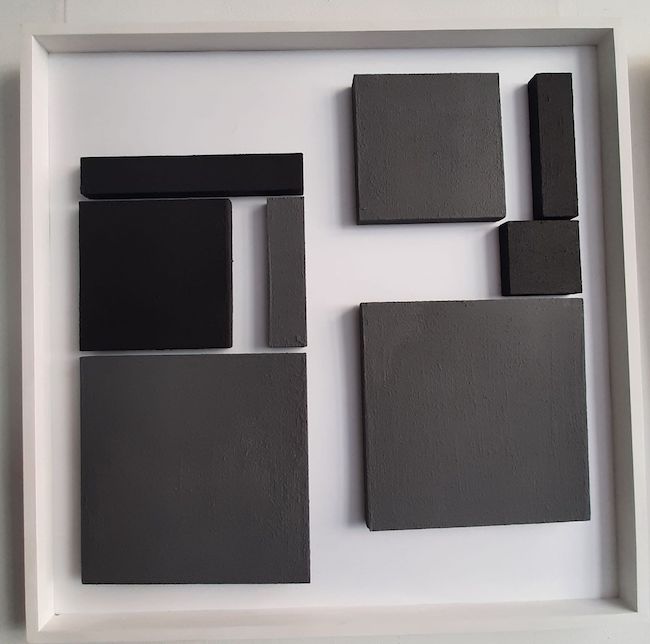

Esponente dell’Astrattismo Geometrico che svela solo a un secondo sguardo il Concettualismo, Stefano Paulon sviluppa la sua ricerca artistica attraverso il rigore della forma che però si apre al possibilismo in virtù dell’utilizzo delle luci e delle ombre generate dai rilievi delle sue opere; in tutti i lavori di questa esposizione la scala di grigi che contraddistingue tutta la sua produzione, si apre al bianco, come se l’introduzione di questo non colore stesse a sottolineare la rottura dello schema costituito dal nero e dai grigi.

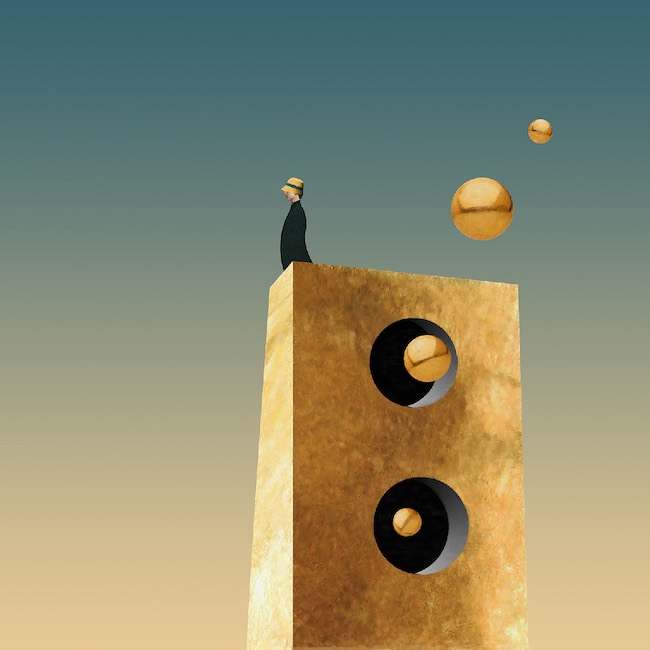

Le figure geometriche non sono disposte come ci si aspetterebbe, sono scomposte, sembra stiano appunto per cadere, sottolineando così la difficoltà di mantenere la linea che ci si è imposti di perseguire. Piero Campanini risponde invece con una figurazione definita e lineare, frutto della mescolanza tra Digital Art, anche quest’ultima figlia di quelle rivoluzioni della seconda metà degli anni Novanta di cui accennavo in precedenza, con una forte impronta Metafisica, e di un apporto pittorico più tradizionale e da cui emerge un punto di vista attiguo a quello di Paulon, poiché anche in queste opere la geometricità emerge seppur in maniera diversa, come simbolo di stabilità in grado di sostenere le incertezze delle figure umane, in prevalenza donne, che dunque sono miniaturizzate di fronte alla vastità degli ambienti che le circondano.

Piramidi, parallelepipedi cavi, cubi, poliedri irregolari, tutto è funzionale ad amplificare la sensazione narrata da Campanini opera per opera, che sembra essere un rimbalzo costante rispetto a quelle di Paulon, come un pendolo che induce l’osservatore a spostarsi da un autore all’altro per riflettere sul senso profondo non solo del dialogo tra i diversi linguaggi espressivi, ma anche dell’esistenza e di ciò che essa rappresenta nel vivere attuale.

Da un lato Paulon racchiude la consapevolezza nelle sue forme geometriche, che però riescono a svelare tutto il percorso di interiorizzazione compiuto dall’artista e della necessità di trattenere il mondo emotivo dentro la solidità della delimitazione strutturale, dall’altro Campanini che invece avverte la necessità di lasciar fuoriuscire tutti i dubbi, le perplessità, i timori e le fragilità dell’essere umano affidandone l’interpretazione alla donna, da sempre più capace di convivere con il mondo delle sensazioni.

L’effetto singolare dell’esposizione è che l’uno si lasci influenzare dall’altro, Campanini enfatizzando l’importanza della geometricità, metafora della logica intesa come gabbia ma anche come contenitore essenziale dentro cui rifugiarsi nel momento in cui diventa impossibile gestire l’emozionalità, e Paulon accogliendo l’instabilità come parte imprescindibile di un vivere troppo mutevole e imprevisto per essere governato solo e unicamente dalle leggi del rigore.

L’interazione tra i due diversi stili e le due personali interpretazioni è suggestiva, sembra essere dominata da un silenzio che nella vicinanza diviene eco, come se l’intenzione esecutiva dell’uno rimbalzasse verso l’altro generando un’amplificazione del concetto espresso che di conseguenza avvolge l’osservatore precipitandolo in una terra di mezzo tra insicurezza e coscienza della possibilità di attingere all’emozione o alla ragione, scoprendo così quanto siano necessarie entrambe per continuare a restare in piedi. Sia Piero Campanini che Stefano Paulon hanno alle spalle un percorso espositivo consolidato, che li ha visti protagonisti di mostre in Italia e all’estero, ricevendo apprezzamento dal pubblico e dagli addetti ai lavori, e il progetto Rigore e Psiche, arricchito di nuove opere di entrambi, sarà presentato mercoledì 3 aprile presso la galleria iKonica di via Porpora 16/a a Milano.

PIERO CAMPANINI-CONTATTI

Email: contatto@pierocampanini.com

Sito web: www.pierocampanini.com

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/campaninipiero.art

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/piero_campanini/

STEFANO PAULON-CONTATTI

Email: stefano.paulon@gmail.com

Facebook: www.facebook.com/stefanopaulon

www.facebook.com/stefanopaulonarchive

Instagram: www.instagram.com/stefanopaulon/

Rigour and Psyche, the tendency of the contemporary individual to seek an elusive perfect balance in the perspective of Piero Campanini and Stefano Paulon

Today’s society, deceptively stable and focused on the race towards innovations and technologies, inexplicably often finds itself destabilised, as if all the certainties on which it has based its existence were only illusorily solid and concrete, while reality instead confronts the human being with the transience, the ephemerality that characterises some of the foundations of modern living that can collapse at any moment. This type of insecurity has returned several times throughout the history of art, and always during conflicts where all certainties were challenged by events external to the individual; and it is on the basis of this constant instability also belonging to contemporaneity that Piero Campanini and Stefano Paulon conceived the project Rigour and Psyche, where their artworks, divergent from a stylistic point of view, become absolutely convergent and in dialogue on the basic concept, that of the human being’s need to find a balance, a centre of himself without which it is impossible to stand.

During the 20th century, the two great wars generated on the one hand an attitude of complete detachment from observed reality precisely in order to generate a distancing on the part of artists from the atrocities they had witnessed, giving rise to a type of art, Abstractionism, which acted almost as a refuge by virtue of its scientific nature, its concentration solely and exclusively on the plastic gesture and the search for perfect balance entrusted to geometric rigour, as in De Stijl and Suprematism, which later evolved into Geometric Abstractionism. This type of language showed the need on the part of the exponents of the various movements, from Piet Mondrian and Theo Van Doesburg to Kasimir Malevic and Manlio Rho and Mario Radice, to contain, to stem that emotional world that would otherwise have ended up overwhelming them, while on the contrary, by abstracting themselves from it they could continue to generate art while maintaining their estrangement from the surrounding reality.

Another expressive reaction, just as relevant and necessary to overcome the dark moments of the war, was that of Surrealism, where the interpreters transposed onto canvas all the anxieties, anguishes and nightmares of the people who had witnessed the destruction and devastation of the fighting; following and translating into images the studies of Sigmund Freud, the analysis of the unconscious of veterans profoundly marked by the atrocities committed or suffered, masters such as Salvador Dali and Max Ernst reproduced apocalyptic and decontextualised scenes where the gaze was deceived by the perfectly figurative pictorial style, only to find themselves in front of terrifying monsters and animals composed of human parts, while others such as René Magritte and Paul Delvaux instead moved more towards a reflection, an analysis of the meaning of existence, of the profound and subtle meaning hidden behind every circumstance, every object, every context, in order to discover its mystery. The peaceful times of the second half of the 20th century, at least as far as the territories of the so-called West were concerned, induced artists to approach social themes, those of inequality and marginalisation that were particularly evident in the large American cities, and struggles for rights, but above all what distinguished the art of those years was the drive to go towards the people, towards a public that was perhaps less cultured but certainly more open to understanding social dynamics such as those dealt with by Street Art or Pop Art, one more desecrating, the other more ironically celebratory. In the contemporary world, the human being has acquired certainties that have gradually proved to be more and more ephemeral, as society has apparently remained tied to the progress and well-being of the late 1990s, while in fact everything has tended towards the illusion that technological progress was the panacea to all difficulties, inducing the human being to forget to remain human. It is in this hinge that is trigged the Rigour and Psyche project, Piero Campanini‘s and Stefano Paulon‘s exploration of everything that belongs to today’s unbalanced existence, one where the individual can no longer fail to come to terms with the awareness of the difficulties of maintaining a balance with himself, by virtue of experiences that have confronted him with unpredictable falls that have then required the effort to get back up and become aware of his own fragility. Different yet complementary, Piero Campanini and Stefano Paulon interpret in a symmetrical manner the instability of present-day living but at the same time the need to find a way to keep oneself poised, resisting the fall but above all finding that centre, that fragile balance that all too often escapes due to circumstances. Exponent of Geometric Abstractionism that only reveals Conceptualism at a second glance, Stefano Paulon develops his artistic research through the rigour of form that, however, opens up to possibilism by virtue of the use of light and shadows generated by the reliefs of his artworks.

In all the works in this exhibition, the grey scale that characterises all his production opens up to white, as if the introduction of this non-colour was to emphasise the break with the scheme constituted by black and grey. The geometric figures are not arranged as one would expect, they are disarranged, they seem to be about to fall, thus underlining the difficulty of maintaining the line one has set out to pursue. Piero Campanini, on the other hand, responds with a definite and linear figuration, the result of a mixture between Digital Art, also daughter of those revolutions of the second half of the 1990s I mentioned earlier, with a strong Metaphysical imprint, and a more traditional pictorial contribution, from which emerges a point of view adjacent to Paulon‘s, because also in these works geometricity emerges, albeit in a different way, as a symbol of stability capable of supporting the uncertainties of the human figures predominantly women, who are therefore miniaturised in the face of the vastness of the environments that surround them. Pyramids, hollow parallelepipeds, cubes, irregular polyhedrons, everything is functional to amplify the sensation narrated work by work from Campanini, which seems to be a constant rebound from those of Paulon, like a pendulum that induces the observer to move from one author to another to reflect on the profound meaning not only of the dialogue between the different expressive languages, but also of existence and what it represents in current living.

On the one hand, Paulon encloses awareness in his geometric forms, which however manage to reveal the entire path of interiorisation undertaken by the artist and the need to hold the emotional world within the solidity of structural delimitation; on the other hand, Campanini, who instead feels the need to let out all the doubts, perplexities, fears and fragility of the human being, entrusting the interpretation to the woman, who has always been more capable of living with the world of sensations. The singular effect of the exhibition is that one allows himself to be influenced by the other, Campanini emphasising the importance of geometricity, a metaphor for logic understood as a cage but also as an essential container within which to take refuge when it becomes impossible to manage emotionality, and Paulon accepting instability as an unavoidable part of a life that is too changeable and unforeseen to be governed solely and exclusively by the laws of rigour. The interaction between the two different styles and the two personal interpretations is evocative, and seems to be dominated by a silence that in its proximity becomes an echo, as if the executive intention of one bounced back to the other, generating an amplification of the concept expressed that consequently envelops the observer, plunging him into a middle ground between insecurity and awareness of the possibility of drawing on either emotion or reason, thus discovering how necessary both are to keep standing. Both Piero Campanini and Stefano Paulon have a well-established exhibition career behind them, which has seen them take part in exhibitions in Italy and abroad, receiving appreciation from the public and insiders. The project Rigore e Psiche, enriched with new works by both of them, will be presented on Wednesday 3 April at the iKonica gallery in via Porpora 16/a in Milan.